Education during the slave period in the United States facts for kids

During the time of slavery in the United States, the education of enslaved African Americans was mostly discouraged. It even became illegal in many Southern states. After 1831, following Nat Turner's slave rebellion, this ban also included free Black people in some states. Even where it was legal, Black people, both in the North and South, had very little chance to go to school.

Contents

Why Education Was Limited

Slave owners saw reading and writing as a danger to slavery. A law in North Carolina said that teaching enslaved people to read and write could make them unhappy and lead to rebellions. If enslaved people could read, they might learn about abolitionists who wanted to end slavery. They could also read about the Haitian Revolution, where enslaved people fought for their freedom, or about the end of slavery in the British Empire.

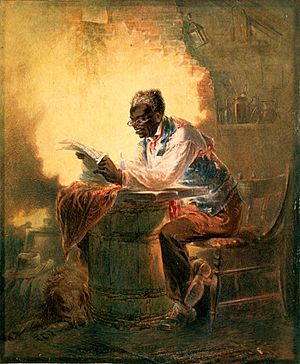

Literacy also meant enslaved people could learn about the Underground Railroad. This secret network helped thousands escape to safe places in the Northern states and Canada. Owners worried that educated enslaved people would become unhappy or disobedient. They believed it was better to keep them uneducated.

Despite these challenges, many free and enslaved African Americans still found ways to learn. They learned in secret from other Black people, from some white people who helped them, and in hidden schools. Enslaved people also shared their culture and information through storytelling, music, and crafts.

In the Northern states, African Americans sometimes had access to formal schools. They were more likely to have basic reading and writing skills. Groups like the Quakers were important in setting up education programs in the North after the American Revolutionary War.

During the colonial period, some religious groups wanted to convert enslaved people to Christianity. For Protestants, reading the Bible was part of this. The First Great Awakening also encouraged education for everyone. Catholic nuns, like Henriette DeLille and Mary Elizabeth Lange, also played a big role in educating enslaved and free Black people in places like Louisiana, Georgia, and Washington DC.

While religious groups encouraged reading for spiritual reasons, writing was often not taught. Writing was seen as a sign of higher status and not necessary for enslaved people. However, some, like Wallace Turnage, learned to read and write after escaping. They might have learned directions to the next town from others. Education often focused on memorizing things, like catechisms and Bible verses.

One famous exception was Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved poet whose writing was admired in both America and Europe.

Even after slavery ended, getting an education was still hard for former slaves and their families. Schools were often segregated by race, and schools for African Americans received much less money, if they existed at all. This problem continued for a long time.

Laws Against Education

South Carolina passed the first laws against slave education in 1740. It became illegal to teach enslaved people to write. This law came after the Stono Rebellion in 1739. Slave owners feared that educated enslaved people could read abolitionist writings or create fake passes to escape. So, they wanted to stop them from communicating through writing. The law said that anyone who taught an enslaved person to write would have to pay a large fine.

In 1759, Georgia made a similar law, banning the teaching of writing to enslaved people. Reading was not banned at first because it was linked to spreading Christianity.

The strictest laws against slave education came after Nat Turner's Revolt in Virginia in 1831. This event shocked the Southern states and led to many new laws over the next 30 years. People feared more slave uprisings and the spread of ideas against slavery. They believed keeping enslaved people uneducated was necessary for their own safety. They didn't want enslaved people to question their authority.

Each state reacted differently. Virginia closed all schools for Black people and forced teachers to leave. Mississippi already had laws against slave literacy. In 1841, it passed a law requiring all free African Americans to leave the state. This was to prevent them from educating or encouraging enslaved people. Other states, like South Carolina, did the same. Laws also required Black preachers to get permission before speaking to a group. Delaware passed a law in 1831 that limited large gatherings of Black people at night.

Even states like Alabama, which had been more moderate, passed strict laws. In 1833, Alabama fined anyone who taught an enslaved person. It also banned any gathering of African Americans unless several slave owners were present or a Black preacher had a special license.

North Carolina had allowed free African-American children to attend schools with white children. But by 1836, it strictly banned public education for all African Americans due to fears of rebellion.

The situation was not much better in the North. African Americans were often not allowed in public schools. Schools like the African Free School were rare.

Secret Learning and Resistance

Even in the 1700s, some enslaved people received religious instruction from their owners. Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved writer, learned in her master's home. She used her skills to write poetry and share her thoughts on slavery. However, not many had her opportunities. Some enslaved people learned to read through Christian lessons, but only if their owners allowed it. Some owners only encouraged reading for small tasks, not writing. They saw writing as a skill only for educated white men.

African-American preachers often tried to teach enslaved people to read in secret. But there were few chances for long periods of teaching. Through spirituals, stories, and other forms of oral tradition, preachers and abolitionists shared important political, cultural, and religious information.

There is proof that enslaved people secretly practiced reading and writing. Slates were found near George Washington's home in Mount Vernon with writings carved into them. Many slates and pencils were found in houses where enslaved people lived. This shows they secretly practiced their skills, often at night. They also might have practiced writing letters in the dirt because it was easier to hide. Enslaved people then shared their new skills with others.

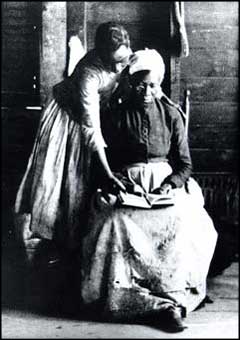

Sometimes, white mistresses ignored the law and taught enslaved people to read. White children were even more likely to break the rules. It was common for enslaved children to carry white children's books to school. They would then sit outside and try to learn by listening through open windows.

The practice of "hiring out" enslaved people also helped spread literacy. As seen in Frederick Douglass's story, those who could read often shared their knowledge. Because enslaved people were often moved around, most plantations eventually had at least a few who could read.

Frederick Douglass wrote in his autobiography that he believed reading and writing were the path from slavery to freedom.

Schools for Free Black People

In the 1780s, a group called the Pennsylvania Abolition Society worked to end slavery. They helped former slaves with education and money. They also helped with legal issues, like making sure they weren't sold back into slavery. Another group, the New York Manumission Society (NYMS), also worked against slavery. They started a school for free Black children, who were usually not allowed in white schools. This school, the African Free School, opened in 1787. It taught hundreds of students each year. The Pennsylvania Abolition Society also started schools for free Black people, often run by formerly enslaved individuals.

Students in these schools learned reading, writing, grammar, math, and geography. The schools held yearly examination days to show the public, parents, and donors what the students had learned. This also showed white people that African Americans could succeed in society. Records show that these schools prepared students for a middle-class life. The African Free School in New York City educated Black students for over 60 years.

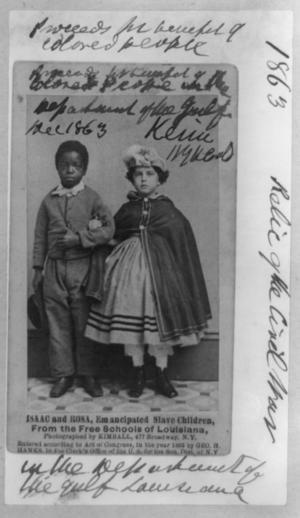

In 1863, a picture of two formerly enslaved children, Isaac and Rosa, studying at the Free School of Louisiana, was widely shared by groups working to end slavery.

It's hard to know exact numbers, but experts like W. E. B. Du Bois estimated that by 1865, about 9% of enslaved people could read at least a little. This number might even be low. In cities and towns, many free Black people and literate enslaved people had more chances to teach others. Both white and Black activists ran secret schools in cities like Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Charleston, Richmond, and Atlanta.

Important Educators

- John Berry Meachum: A Black pastor who created a Floating Freedom School in 1847 on the Mississippi River to get around anti-literacy laws. James Milton Turner attended his school.

- Margaret Crittendon Douglass: A white woman who wrote a book after being jailed in Virginia in 1853 for teaching free Black children to read.

- Catherine and Jane Deveaux: A Black mother and daughter who, with Catholic nun Mathilda Beasley, ran secret schools in Savannah, Georgia in the 1800s.

- Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange: With her Oblate Sisters of Providence, she founded St. Frances Academy in 1828.

- Mother Henriette DeLille: With her Sisters of the Holy Family, she founded schools in New Orleans in the mid-to-late 1800s, including St. Mary's Academy.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |