First Great Awakening facts for kids

The First Great Awakening was a big religious movement that happened in the 1730s and 1740s. It swept across Great Britain and its thirteen colonies in North America. This movement deeply changed Protestantism, as people wanted to feel a stronger personal connection to their faith.

The Great Awakening helped create a new kind of Christianity called Anglo-American evangelicalism. This was a movement that brought together different Protestant churches. In the United States, it's usually called the "Great Awakening." In the United Kingdom, it's known as the "Evangelical Revival."

Important leaders like George Whitefield, John Wesley, and Jonathan Edwards taught about salvation and spiritual rebirth. They believed that God's Holy Spirit was working in new ways. Preachers often spoke without notes, which made listeners feel a deep personal need for salvation through Jesus Christ. They also encouraged people to look inside themselves and live by new moral standards.

A key idea was that becoming a Christian wasn't just about understanding rules. It had to be a "new birth" felt in the heart. Revivalists also taught that Christians could expect to feel sure about their salvation.

While the Evangelical Revival brought many Christians together, it also caused some churches to split. Some people supported the revivals, while others thought they caused disorder. They worried about preachers who traveled a lot and weren't formally trained. In England, Methodism grew out of the work of Whitefield and Wesley. In the American colonies, the movement divided Congregational and Presbyterian churches. But it made the Methodist and Baptist churches much stronger.

Evangelical preachers wanted to include everyone in their message. This meant people of all genders, races, and social classes. In the American colonies, especially in the South, more African slaves and free blacks became Christians. The movement also led to the creation of new missionary groups.

Contents

Religious Awakenings in Europe

Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom saw the Great Awakening as part of a larger religious movement in Europe. This movement was called Pietism. Pietism focused on having a heartfelt faith instead of just following strict rules. Pietists believed that personal religious experience was more important than old church disagreements.

Pietism helped prepare Europe for these revivals. A key leader in central Europe was Nicolaus Zinzendorf. In 1722, he invited members of the Moravian Church to live on his land. This community, called Herrnhut, became a place of religious revival. It also welcomed other Protestants. Moravian groups later helped the Evangelical Revival in England.

Evangelical Revival in Britain

England's Methodist Movement

In England, the movement is known as the Evangelical Revival. Its main leaders were three Anglican priests: brothers John Wesley and Charles Wesley, and their friend George Whitefield. They started what would become Methodism. They were part of a religious group at Oxford University called the Holy Club. People called them "Methodists" because of their careful and disciplined religious life.

George Whitefield joined the Holy Club in 1733. He read books that helped him understand that true religion was about a deep connection with God. He realized that even though he had been very religious, he didn't know "true religion" until he sought this "new birth." After a time of spiritual struggle, Whitefield felt a powerful conversion in 1735. He began preaching in 1736 in Bristol and London.

Whitefield's preaching drew huge crowds. People loved his simple message about needing a "new birth." His style was very dramatic and emotional. He would sometimes cry or act out Bible characters. By the time he left England for the colony of Georgia in 1737, he was very famous.

John Wesley went to Georgia in 1735 as a missionary. There, he met members of the Moravian Church. He was impressed by their strong faith and their belief that Christians could be sure of their faith. Wesley began to question his own faith. He wrote in his journal, "I who went to America to convert others was never myself converted to God."

Back in London, Wesley joined a Moravian group. In May 1738, he had a spiritual experience at a meeting on Aldersgate Street. He felt his "heart strangely warmed" and knew that he trusted in Christ alone for salvation. Wesley saw this as his own evangelical conversion. It gave him the assurance he had been looking for.

John Wesley returned to England in September 1738. Both he and Charles were preaching in London churches. Whitefield came back to England in December 1738. Whitefield's traveling preaching was controversial. Many churches wouldn't let him preach. He had to fight against Anglicans who didn't like the Methodists or the idea of the "New Birth."

In February 1739, some priests refused Whitefield permission to preach. So, he started preaching outdoors in a mining community near Bristol. Preaching outdoors was common in Wales and Scotland, but new in England. Whitefield also preached in other priests' areas without permission. Within a week, he was preaching to 10,000 people. By May, he was preaching to 50,000 people in London.

Wesley was at first unsure about preaching outdoors. But he changed his mind, saying "all the world [is] my parish." On April 2, 1739, Wesley preached to about 3,000 people near Bristol. From then on, he preached wherever he could gather a crowd.

Wesley and Whitefield appointed lay (non-clergy) preachers and leaders. Methodist preachers focused on people the Church of England had "neglected." Wesley organized new converts into Methodist societies. These societies had smaller groups called classes. In these classes, people shared their sins and encouraged each other. They also had "love feasts" where they shared their faith stories.

Methodists believed in three main things:

- Everyone is born "dead in sin."

- People are "saved by faith alone."

- Faith leads to inner and outer holiness.

The evangelicals faced a lot of opposition, including attacks and mob violence. But they grew stronger despite this. John Wesley's organizing skills helped make Methodism a major movement. By the time he died in 1791, there were over 71,000 Methodists in England and over 43,000 in America.

Wales and Scotland's Revivals

The Evangelical Revival first started in Wales. In 1735, Howell Harris and Daniel Rowland had religious conversions. They began preaching to large crowds across South Wales, starting the Welsh Methodist revival.

In Scotland, religious revivals had happened since the 1620s. In the 18th century, ministers like Ebenezer Erskine and William M'Culloch led the Evangelical Revival there. Many ministers in the Church of Scotland held evangelical beliefs.

Great Awakening in North America

Early Religious Stirrings

In the early 1700s, the 13 American colonies had many different religions. In New England, the Congregational churches were the official religion. In the Middle Colonies, many different churches existed side-by-side. In the Southern Colonies, the Anglican church was official, but there were also many Baptists and Presbyterians.

At this time, church membership was low. Also, new ideas from the Enlightenment caused some people to turn away from traditional faith. In response, ministers who were influenced by Puritanism, Presbyterianism, and European Pietism called for a religious revival. This led to a new kind of Protestantism that focused on times of revival and on sinners personally experiencing God's love.

In the 1710s and 1720s, revivals became more common in New England. These early revivals were local. But after an earthquake in 1727, revivals started getting more publicity. They grew from local events to regional and even transatlantic ones.

In the 1720s and 1730s, an evangelical group formed in the Presbyterian churches of the Middle Colonies. It was led by William Tennent, Sr. He started a school called the Log College to train revivalist ministers. Gilbert Tennent, William's son, was influenced by Dutch Reformed minister Theodorus Jacobus Frelinghuysen. Frelinghuysen believed in personal conversion and living a holy life. His revivals were "forerunners" of the Great Awakening in the Middle Colonies.

The Northampton Revival

One of the most important revivals happened in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1734–1735. It was led by Congregational minister Jonathan Edwards. In the fall of 1734, Edwards preached sermons about being "saved by faith alone." The community's response was amazing, especially among young people. Edwards wrote that the town was "never so full of Love, nor so full of Joy, nor so full of distress as it has lately been." The revival spread to 25 towns before it slowed down in 1737.

Edwards believed that conversion was a move from spiritual emptiness to joy. He thought that God chose who would be saved. Services became more emotional, and some people had visions. Edwards carefully supported these experiences as long as they led people to believe more in God's glory. Similar experiences happened in most revivals of the 18th century.

Edwards wrote a book about the Northampton revival called A Faithful Narrative. It was published in England and made Edwards famous. This book became a guide for how other revivals would be run.

Whitefield, Tennent, and Davenport

George Whitefield first came to America in 1738. He preached in Georgia and started an orphanage. Whitefield returned to the colonies in November 1739. He preached in Philadelphia, New York, and then the South. He was popular among Dutch, German, and British communities.

In 1740, Whitefield toured New England. He preached in Newport, Rhode Island, and then in Boston, Massachusetts. He preached to huge crowds, sometimes 8,000 to 15,000 people outdoors. He also preached at Harvard University and Yale University. Whitefield believed that many preachers in New England were not truly converted.

Whitefield asked Gilbert Tennent to preach in Boston to keep the revival going. Tennent agreed and toured New England for three months. Like Whitefield, Tennent's preaching drew large crowds and caused many conversions. But it also created a lot of debate.

In the summer of 1741, James Davenport followed Tennent. He was even more controversial. He criticized ministers he thought were "unconverted." He was arrested in Connecticut for preaching without permission. He was found mentally ill and sent away. Davenport later apologized for his extreme actions.

Many other traveling preachers followed Whitefield, Tennent, and Davenport. But in New England, local ministers mostly kept the Awakening going. Between 1740 and 1743, New England had a "great and general Awakening." People became more interested in religious experiences, and emotional preaching was common. Many people had strong emotional reactions during conversion, like fainting or weeping. More people prayed and read the Bible. It's thought that 20,000 to 50,000 new members joined New England's Congregational churches.

By 1745, the Awakening started to slow down. But revivals continued to spread to the southern backcountry and slave communities in the 1750s and 1760s.

Conflicts and Divisions

The Great Awakening caused arguments within Protestant churches. This often led to splits between "New Lights" (who supported the revivals) and "Old Lights" (who opposed them). Old Lights thought the emotional displays and traveling preachers caused disorder. They preferred formal worship and educated ministers. They called revivalists ignorant or dishonest. New Lights accused Old Lights of caring more about social status than saving souls.

In New England, Congregational churches had 98 splits. It's estimated that churches were divided into about one-third New Lights, one-third Old Lights, and one-third who saw good in both sides. About 100 "Separatist" congregations were formed. These groups wanted proof of conversion for church membership. They were sometimes treated unfairly in Connecticut.

The Baptist churches benefited the most from the Great Awakening. They were small before the revival, but grew a lot in the late 1700s. Many former New Light Congregationalists became Baptists.

In Presbyterian churches, the "Old Side–New Side Controversy" happened. The "Old Side" was against the revivals, and the "New Side" supported them. The New Side believed that simply following rules wasn't enough without a personal religious experience. In May 1741, the Old Side kicked out the New Side. The New Side then formed its own group.

What Happened Next

The Great Awakening made different religious groups a key part of American Christianity. Even though it divided many churches, it also encouraged unity among different Protestant groups. Evangelicals believed that the "new birth" connected them, even if they disagreed on small points of belief. This allowed Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists to work together.

Over time, New Lights became less extreme, and evangelicalism became more common. By 1758, the Old Side and New Side Presbyterians reunited. The New Side had grown much larger. While the intense excitement of the Awakening faded, the idea of revivals and personal conversion remained important in Presbyterianism for many years.

The Great Awakening also led to new evangelical schools. In 1746, New Side Presbyterians founded what is now Princeton University. In 1754, Eleazar Wheelock started what would become Dartmouth College. It was first meant to train Native American boys for missionary work. Even Yale University, which was at first against the revivals, later embraced them.

Revival Theology

The Great Awakening was not the first religious revival. But it was the first time a common evangelical identity appeared. This identity was based on a similar understanding of salvation, preaching the gospel, and conversion. Revival theology focused on the "way of salvation." This meant the steps a person takes to gain Christian faith and then live that faith.

Key figures like George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards preached a form of Calvinism that was influenced by Puritanism. They believed that religion was not just about thinking, but also about feeling it in the heart. This revival theology had three main steps:

- Conviction of sin: This was preparing for faith. People realized they were sinners and felt sorrow.

- Conversion: This was when a person had a spiritual awakening, repented, and believed.

- Consolation: This was seeking and receiving assurance of salvation. This whole process usually took a long time.

Feeling Convicted of Sin

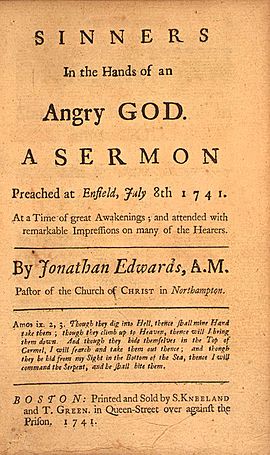

Conviction of sin was the step that prepared someone for salvation. This stage often lasted weeks or months. When under conviction, non-believers realized they were guilty of sin. They felt sad and worried. Revivalists preached about God's moral law to show how holy God is. This helped spark conviction in people who were not yet converted. Jonathan Edwards' sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" is a famous example of this kind of preaching.

Revivalists also preached about original sin and unconditional election. Original sin means that humans are naturally inclined to rebel against God. They cannot start or earn salvation on their own. Unconditional election means that God chose who would be saved before the world was created. Preaching these ideas made people feel guilty and helpless. They felt that God was in complete control of their salvation.

Revivalists told those under conviction to use "means of grace." These were spiritual practices like prayer, Bible study, church attendance, and improving one's personal morals. While no human action could create saving faith, revivalists taught that these practices might make conversion more likely.

The intense emotional reactions during the Awakening were also discussed. Some people would faint, sob, or cry loudly. Moderate evangelicals were careful about these reactions. They didn't encourage or discourage them. But they understood that people might show their conviction in different ways.

The Conversion Experience

The conviction stage lasted a long time because people were waiting to see signs of regeneration in their lives. Revivalists believed that regeneration, or the "new birth," was not just saying you believe. It was an instant, supernatural work of the Holy Spirit. It gave someone "a new awareness of the beauty of Christ, new desires to love God, and a firm commitment to follow God's holy law." While it happened instantly, a convert might only slowly realize it had occurred.

Regeneration always came with saving faith, repentance, and love for God. These were all parts of the conversion experience. This experience usually took several days or weeks with a pastor's help. True conversion began when the mind opened to a new understanding and love of the gospel. After this, converts put their faith in Christ, trusting only him for salvation. At the same time, they would hate sin and want to remove it from their hearts. This set the stage for a life of repentance. Revivalists separated true conversion (motivated by love for God) from false conversion (motivated by fear of hell).

Finding Assurance

True conversion meant a person was among God's chosen. But even a person with saving faith might doubt their salvation. Revivalists taught that feeling sure about salvation came from growing as a Christian. Converts were encouraged to check their own spiritual progress. Jonathan Edwards' book Religious Affections helped converts look for real "religious affections," or spiritual desires. These included selfless love for God and certainty in the gospel.

However, it wasn't enough to just think about past experiences. Revivalists taught that assurance could only be gained by actively trying to grow in grace and holiness. This meant getting rid of sin and using the means of grace. Edwards' book emphasized "Christian practice" as the most important sign of true faith. Finding assurance required effort and could take months or even years.

Social Impact

Women's Roles

The Awakening greatly impacted women's lives. While they rarely preached, they were encouraged to explore their feelings and share them. This led many women to keep diaries or write memoirs. For example, Hannah Heaton's autobiography tells about her experiences in the Great Awakening.

Phillis Wheatley was the first published black female poet. She became a Christian as a child. Her poems often showed her faith. She wrote about being brought from Africa and finding Christianity. She also wrote a poem about George Whitefield after he died. Sarah Osborn, a Rhode Island schoolteacher, also wrote about her spiritual journey during this time.

African Americans and the Awakening

The First Great Awakening changed how Americans understood God, themselves, and religion. In the southern colonies, northern Baptist and Methodist preachers converted both white and black people. Some were enslaved, while others were free. White church members began to welcome black individuals. They took their religious experiences seriously and allowed them to have active roles in churches, sometimes even as preachers.

The idea of spiritual equality appealed to many enslaved people. As African religious traditions faded in North America, many Black people became Christians for the first time.

Evangelical leaders in the southern colonies often had to deal with slavery. Many revival leaders said that slaveholders should educate enslaved people so they could read the Bible. Many Africans finally got some education.

George Whitefield's sermons spoke of equality, but for Africans in the colonies, this mostly meant spiritual equality. Whitefield criticized slaveholders who were cruel or didn't educate enslaved people. But he did not want to end slavery. He even lobbied to bring slavery back to Georgia and became a slave owner himself. Whitefield believed that after conversion, enslaved people would find true equality in Heaven. Despite his views on slavery, Whitefield influenced many Africans.

Samuel Davies was a Presbyterian minister who later became president of Princeton University. He preached to many enslaved Africans who converted to Christianity. Davies wrote about the religious passion of an enslaved man he met. The man said, "I am a poor slave, brought into a strange country, where I never expect to enjoy my liberty. ... I now see such a life will never do, and I come to you, Sir, that you may tell me some good things, concerning Jesus Christ, and my Duty to GOD, for I am resolved not to live any more as I have done."

Davies often heard such excitement from Black people during the revivals. He believed that Black people could learn as much as white people if given a good education. He encouraged slaveholders to let enslaved people become literate so they could read the Bible.

The emotional worship of the revivals appealed to many Africans. African leaders began to emerge from the revivals. These leaders helped start the first Black churches in the American colonies. Before the American Revolution, the first black Baptist churches were founded in Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia.

See also

In Spanish: Primer Gran Despertar para niños

In Spanish: Primer Gran Despertar para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |