Jonathan Edwards (theologian) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jonathan Edwards

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||

| 3rd President of Princeton University | |||||||||||||||

| In office 1758–1758 |

|||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Aaron Burr, Sr. | ||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jacob Green (acting) | ||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||

| Born | October 5, 1703 East Windsor, Connecticut, British America |

||||||||||||||

| Died | March 22, 1758 (aged 54) Princeton, New Jersey, British America |

||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Sarah Pierpont

(m. 1727) |

||||||||||||||

| Children | Sarah, Jerusha, Esther, Mary, Lucy, Timothy, Susannah, Eunice, Jonathan, Elizabeth, and Pierpont | ||||||||||||||

| Relatives |

|

||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Yale College | ||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Pastor, theologian, missionary | ||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

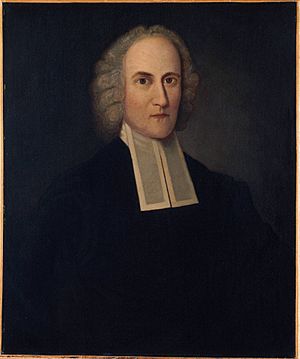

Jonathan Edwards (born October 5, 1703 – died March 22, 1758) was an important American preacher, thinker, and Congregationalist religious scholar. Many people see him as one of America's most important and original religious thinkers.

Edwards's ideas were wide-ranging, but they came from his Puritan background. He believed in the baptism of babies and followed the Westminster and Savoy Confessions. Recent studies show that Edwards based his work on ideas of beauty, harmony, and what is ethically right. The Age of Enlightenment also greatly shaped his way of thinking.

Edwards played a key role in the First Great Awakening, a time of religious excitement. He led some of the first revivals in 1733–35 at his church in Northampton, Massachusetts. His religious ideas led to a special way of thinking called New England theology.

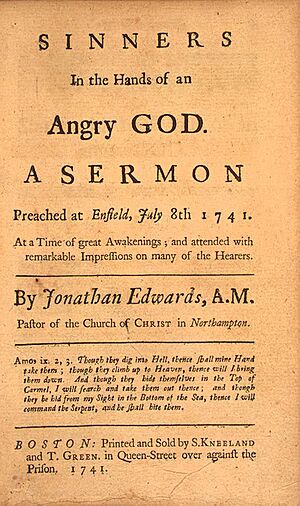

In 1741, Edwards gave his famous sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God". This happened during another revival, after George Whitefield visited the Thirteen Colonies. Edwards is also known for his many books, like The End for Which God Created the World and The Life of David Brainerd. This last book inspired many missionaries in the 1800s. His book Religious Affections is still read by many Calvinist Evangelicals today.

Edwards died from a smallpox shot soon after becoming president of the College of New Jersey in Princeton. He was the grandfather of Aaron Burr, who later became the third Vice President of the United States.

Contents

Biography

Early life

Jonathan Edwards was born on October 5, 1703. He was the only son of Timothy Edwards (1668–1759), a minister in East Windsor, Connecticut. His father also taught boys to help pay the bills. Jonathan's mother, Esther Stoddard, was the daughter of Rev. Solomon Stoddard from Northampton, Massachusetts. She was known for being very smart and independent. Jonathan was the fifth of 11 children.

Jonathan's father and older sisters, who were all well-educated, prepared him for college. His sister Esther, the oldest, even wrote a funny paper about the soul not being physical. People sometimes thought Jonathan wrote it by mistake.

He started Yale College in 1716, when he was almost 13 years old. The next year, he learned about John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which greatly influenced him. During college, he kept notebooks on "The Mind," "Natural Science" (where he talked about atomic theory), "The Scriptures," and "Miscellanies." He planned a big work on nature and philosophy.

Edwards was very interested in natural history. When he was just 11, he wrote an essay about how some spiders use silk to fly. He later changed this essay to fit in with scientific writings of the time. Even after studying theology for two years after Yale, he kept his interest in science. While some scientists and clergy of his time thought science led to deism (belief in a distant God), Edwards believed nature showed God's amazing design. He often went into the woods to pray and enjoy nature's beauty.

Edwards was fascinated by the discoveries of Isaac Newton and other scientists. Before becoming a full-time minister, he wrote about light, optics, and spiders. He worried about people who focused too much on material things and only on human reason. However, he believed that the laws of nature came from God and showed God's wisdom and care. Edwards's sermons and writings often talked about God's beauty and how important aesthetics (the study of beauty) are in spiritual life. Some think he was ahead of his time in this area.

From 1722 to 1723, he worked for eight months as a temporary pastor at a small Presbyterian church in New York City. The church asked him to stay, but he said no. After studying at home for two months, he became one of two tutors at Yale from 1724–1726. They led the college because the previous leader had left to join the Anglican Church and had not been replaced.

Edwards wrote about his life from 1720 to 1726 in his diary and in rules he made for himself. He had long searched for salvation and finally felt sure of his own conversion during his last year in college. He used to think the idea of God choosing some for salvation and others for damnation was "horrible." But then he found it "exceedingly pleasant, bright and sweet." He also found great joy in nature's beauty and loved the hidden meanings in the Song of Solomon. Along with these joyful experiences, his "Resolutions" showed his serious side. He was almost strict with himself, wanting to live earnestly, not waste time, and be very careful about eating and drinking.

On February 15, 1727, Edwards became a minister in Northampton. He was an assistant to his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard, who was also a famous minister. Edwards was a scholar-pastor, meaning he spent about 13 hours a day studying. That same year, he married Sarah Pierpont. Sarah was 17 and came from a well-known New England religious family. Her father, James Pierpont, helped start Yale College. Sarah's deep faith had inspired Edwards since she was 13. She was cheerful, a good homemaker, a great wife, and the mother of their 11 children, including Esther Edwards. Edwards believed in traditional roles for husbands and wives.

Solomon Stoddard died on February 11, 1729. This left Jonathan Edwards with the big job of leading one of the largest and wealthiest churches in the colony by himself. Its members were proud of their good behavior, culture, and reputation. Scholar John E. Smith said that Edwards tried to save Christianity from being too focused on reason and from doubt.

Great Awakening

On July 8, 1731, Edwards gave a speech in Boston called "God Glorified in the Work of Redemption." This was his first public challenge to Arminianism, a different religious idea. He stressed that God has complete power in saving people. He said that while God created humans pure, it was only by God's "good pleasure" and "grace" that anyone received the faith needed for holiness. He believed God could refuse this grace without being unfair. In 1733, a religious revival started in Northampton. It became so strong in the winter of 1734 and spring of 1735 that it affected the town's businesses. In six months, nearly 300 out of 1,100 young people joined the church.

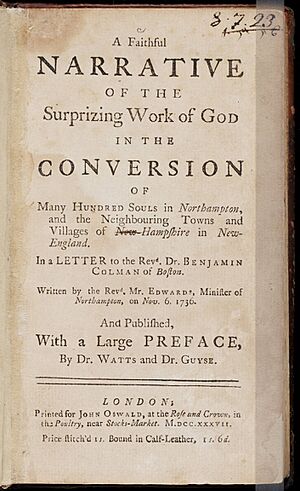

The revival allowed Edwards to study how people experienced religious conversion. He wrote down his detailed observations in A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (1737). A year later, he published Discourses on Various Important Subjects, which included five sermons that were very powerful during the revival. One of the most effective was The Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners. Another sermon, published in 1734, A Divine and Supernatural Light, explained what he saw as the main idea of the revival: that God's Spirit gives a special, direct, and supernatural understanding to the soul.

By 1735, the revival had spread across the Connecticut River Valley and possibly even to New Jersey. However, people started to criticize the revival. Many in New England worried that Edwards had led his church into extreme behavior.

In the summer of 1735, the strong religious feelings took a dark turn. Many New Englanders were affected by the revivals but did not feel converted. They became convinced they were doomed. Edwards wrote that "multitudes" felt urged—he believed by Satan—to take their own lives.

Despite these problems and the slowing down of religious excitement, news of the Northampton revival and Edwards's leadership reached England and Scotland. Around this time, Edwards met George Whitefield, who was traveling through the Thirteen Colonies on a revival tour in 1739–40. The two men might not have agreed on every small detail. Whitefield was more comfortable with strong emotions during revivals than Edwards was. But both were very passionate about preaching the Gospel. They worked together to plan Whitefield's trip, first to Boston and then to Northampton. When Whitefield preached at Edwards's church, he reminded them of their revival a few years earlier. This deeply moved Edwards, who cried throughout the service, and many in the church were also touched.

Revivals started again, and Edwards preached his most famous sermon, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, in Enfield, Connecticut, in 1741. This sermon is often seen as an example of "fire and brimstone" preaching from colonial revivals. However, descriptions of Edwards's actual preaching style show he did not shout. He spoke in a quiet, emotional voice. He slowly led his audience from one point to the next, towards a clear conclusion: they were lost without God's grace. While modern readers might focus on the idea of damnation in such a sermon, historian George Marsden reminds us that Edwards was not saying anything new. He assumed his New England audience already knew about God's rescue. The challenge was getting them to seek it.

The revival faced opposition from some traditional Congregationalist ministers. In 1741, Edwards published The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God to defend the revivals. He specifically addressed the criticized behaviors like fainting, shouting, and shaking. He insisted that these "bodily effects" did not truly show if God's Spirit was at work or not. The feelings against the revival were so strong in some churches that in 1742, he felt he needed to write a second defense, Thoughts on the Revival in New England. In this paper, his main point was the great moral improvement in the country. He also defended appealing to emotions and said it was sometimes necessary to preach about terror, even to children. He believed that in God's eyes, children "are young vipers... if not Christ's."

Edwards thought "bodily effects" were not the main part of God's work. But his own deep faith and his wife's experiences during the Awakening (which he described in detail) made him believe that God's presence often affects the body. He used the Bible to support this view. In response to Edwards, Charles Chauncy wrote Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in New England in 1743. He also secretly wrote The Late Religious Commotions in New England Considered that same year. In these works, he argued that a person's actions were the only true sign of conversion. The general meeting of Congregational ministers in Massachusetts seemed to agree. They protested "disorders in practice" that had recently happened. Despite Edwards's good writing, many people widely believed that "bodily effects" were seen by revival supporters as the real signs of conversion.

To change this idea, Edwards preached a series of sermons in Northampton between 1742 and 1743. These were later published as Religious Affections (1746). This book explained his ideas about "distinguishing marks" in a more philosophical way. In 1747, he joined a prayer movement that started in Scotland. That same year, he published An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God's People in Extraordinary Prayer for the Revival of Religion. In 1749, he published a book about David Brainerd, a missionary who had lived with Edwards's family for several months and died in Northampton in 1747. Edwards's daughter Jerusha had often cared for Brainerd. Some rumored they were engaged, but there is no proof. Edwards used Brainerd's life and work as a study for his ideas about conversion, taking many notes on his religious experiences.

Enslaver and slavery advocate

Jonathan Edwards owned several enslaved Black children and adults during his life. This included a young teenager named Venus, who was taken from Africa and bought by Edwards in 1731, a boy named Titus, and a woman named Leah. In a 1741 paper, Edwards defended owning people who were debtors, war captives, or born into slavery in North America. However, he did not support the Atlantic slave trade.

Edwards's role as an enslaver and supporter of slavery has been a topic of discussion recently. Some people strongly criticize him, while others say he was simply a product of his time. Other commentators try to value Edwards's religious ideas while still regretting his involvement in slavery.

Later years

In 1748, Edwards had a major disagreement with his church members. The Half-Way Covenant, adopted in the 1600s, allowed people to be baptized and have some church privileges just by being baptized. However, it did not allow them to take part in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. Edwards's grandfather, Stoddard, had been even more open, believing that the Lord's Supper could help people become truly religious and that baptism was enough for all church privileges.

As early as 1744, in his sermons on Religious Affections, Edwards had shown he did not like this practice. That same year, he read out the names of young church members suspected of reading inappropriate books. He also named those who would be witnesses in the case. It has often been said that the list did not separate the accused from the witnesses, causing a big uproar in the church. However, research by Patricia Tracy suggests this might not be true, as the names were likely distinguished. Those involved were eventually disciplined for disrespecting the investigators, not for the original incident. In any case, this event made the relationship between Edwards and his church worse.

Edwards's preaching became unpopular. For four years, no one came forward to join the church. When someone finally did in 1748, Edwards used his strict tests for joining. The person refused to follow them, and the church supported him. This created a complete break between the church and Edwards. He was not even allowed to discuss his views from the main pulpit. He was only allowed to present his ideas on Thursday afternoons. Many visitors came to hear his sermons, but his own church members did not. A meeting was held to decide the issue between the minister and his people. The church chose half of the council members, and Edwards was allowed to choose the other half. However, his church limited his choices to one county where most ministers were against him. The church council voted 10 to 9 to end his role as pastor.

The church members then voted by more than 200 to 23 to agree with the council's decision. Finally, a town meeting voted that Edwards should not be allowed to preach in the Northampton church. However, he continued to live in the town and preach there at the church's request until October 1751. In his "Farewell Sermon," he spoke about a future time when the minister and his people would stand before God. In a letter to Scotland after he was dismissed, he said he preferred the Presbyterian way of church government over the congregational polity (where each church governs itself). His ideas at the time were not unpopular throughout New England. His belief that the Lord's Supper does not cause spiritual rebirth, and that only those who truly believe should take part, has since become a standard idea in New England Congregationalism, largely thanks to his student Joseph Bellamy.

Edwards was in high demand. He could have found a church in Scotland, and he was asked to lead a church in Virginia. He turned down both offers to become a pastor in 1751 at the church in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He also became a missionary to the Housatonic Indians, taking over after John Sergeant died. He preached to the Indians through an interpreter. He bravely and successfully defended their interests by speaking out against white people who were using their official positions to gain wealth from the Indians. During this time, he met Judge Joseph Dwight, who was a trustee of the Indian Schools. In Stockbridge, Edwards wrote the Humble Relation (1752), which was a response to Solomon Williams, a relative and strong opponent of Edwards's ideas about who should be allowed to fully join the church. He also wrote the important books that made him famous as a religious philosopher. These included essays on Original Sin, The Nature of True Virtue, The End for which God created the World, and his major work on the Will. This last book was written in four and a half months and published in 1754 as An Inquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions Respecting that Freedom of the Will.

Aaron Burr, Sr., Edwards's son-in-law, died in 1757. He had married Esther Edwards five years earlier, and they were the parents of Aaron Burr, who later became the U.S. vice president. Edwards felt he was "in the decline of life" and not strong enough for the job. But he was convinced to replace Burr as president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He started this role on February 16, 1758. He gave weekly writing assignments on religious topics to the senior class.

Death and legacy

Soon after becoming president of the College of New Jersey, Edwards, who strongly supported smallpox inoculations, decided to get one himself. He wanted to encourage others to do the same. Edwards was never very healthy, and he died from the inoculation on March 22, 1758. He left behind eleven children (three sons and eight daughters). Edwards's grave is in Princeton Cemetery. His long, emotional epitaph (words on a tombstone) is written in Latin on his flat gravestone. It praises his life and career and expresses sadness at his death. It follows an old tradition of praising the dead and asking passersby to stop and mourn.

The followers of Jonathan Edwards and his students became known as the New Light Calvinist ministers. Important students included Samuel Hopkins, Joseph Bellamy, Jonathan Edwards Jr., and Gideon Hawley from the New Divinity school. Through a system where young ministers lived with older ones, they eventually filled many pastor positions in the New England area. Many of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards's descendants became important people in the United States. These include Aaron Burr and college presidents Timothy Dwight, Jonathan Edwards Jr., and Merrill Edwards Gates. Jonathan and Sarah Edwards were also ancestors of Edith Roosevelt, the writer O. Henry, the publisher Frank Nelson Doubleday, and the writer Robert Lowell. Because so many of Edwards's descendants were famous, some scholars in the Progressive Era saw him as proof of eugenics (a now-discredited idea about improving the human race). His biographer George Marsden notes that the Edwards family produced many religious leaders, thirteen college presidents, sixty-five professors, and many other people who achieved great things.

Edwards's writings and beliefs still influence people and groups today. Early missionaries of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions were influenced by his writings. After the Second World War, Edwards's work became popular again among scholars, starting with Perry Miller's important book. The Banner of Truth Trust and other publishers continue to print Edwards's works. Most of his major works are now available through a series published by Yale University Press, which has been going on for over thirty years. Each volume has helpful introductions by its editor. Yale also created the Jonathan Edwards Project online. Author and teacher Elisabeth Woodbridge Morris honored him, her ancestor, in two books: The Jonathan Papers (1912) and More Jonathan Papers (1915). In 1933, Jonathan Edwards College at Yale, the first of its 12 residential colleges, was named after him. The Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University was founded to provide scholarly information about his writings. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America remembers Edwards today as a teacher and missionary on March 22. The modern poet Susan Howe often writes about Edwards's manuscripts and notebooks, which are kept at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. She notes how some of his notebooks were made from silk paper that his sisters and wife used for making fans. Howe also argues in My Emily Dickinson that the poet Emily Dickinson was greatly influenced by Edwards's writings. She believes Dickinson "took both his legend and his learning... then applied the freshness of his perception to the dead weight of American poetry as she knew it."

Works

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University has most of Edwards's surviving writings. This includes over a thousand sermons, notebooks, letters, printed materials, and other items. Two of Edwards's handwritten sermons and other related historical texts are kept at The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia. All of Edwards's works, including those never published before, are available online through the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University website. The Works of Jonathan Edwards project at Yale has been publishing scholarly editions of his works, based on new copies of his handwritten papers, since the 1950s. There are 26 volumes so far. Many of Edwards's works have been printed again and again. Some of his main works include:

- Charity and its Fruits

- Protestant Charity or The Duty of Charity to the Poor, Explained and Enforced (1732)

- A Dissertation Concerning the End for Which God Created the World

- Contains Freedom of the Will and Dissertation on Virtue, slightly modified for easier reading

- Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God

- A Divine and Supernatural Light, Immediately Imparted to the Soul by the Spirit of God (1734)

- A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton

- The Freedom of the Will

- A History of the Work of Redemption including a View of Church History

- The Life and Diary of David Brainerd, Missionary to the Indians

- The Nature of True Virtue

- Original Sin

- Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival in New England and the Way it Ought to be Acknowledged and Promoted

- Religious Affections

Sermons

The words of many of Edwards's sermons have been saved. Some are still published and read today in collections of American literature. Among his more well-known sermons are:

- "The Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners"

- "The Manner of Seeking Salvation"

- "Pressing into the Kingdom of God"

- "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God"

- "The Folly Of Looking Back In Fleeing Out Of Sodom"

See also

In Spanish: Jonathan Edwards (teólogo) para niños

In Spanish: Jonathan Edwards (teólogo) para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |