Phillis Wheatley facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Phillis Wheatley

|

|

|---|---|

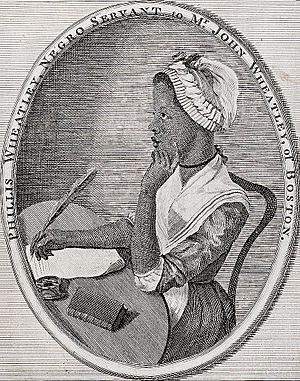

Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, believed by some to be by Scipio Moorhead

|

|

| Born | c. 1753 West Africa |

| Died | December 5, 1784 (aged 31) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | English |

| Period | American Revolution |

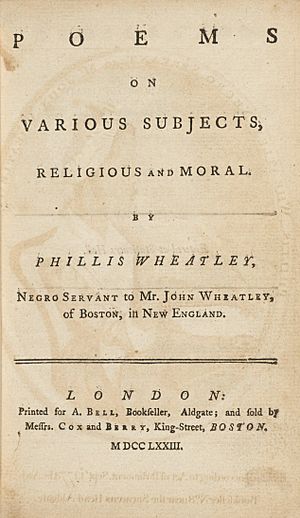

| Notable works | Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) |

| Spouse | John Peters |

| Children | Uncertain. Up to three with none surviving past early childhood. |

Phillis Wheatley Peters, sometimes spelled Phyllis or Wheatly (born around 1753 – died December 5, 1784), was an American writer. She is known as the first African-American author to publish a book of poetry.

Phillis was born in West Africa. When she was about seven or eight years old, she was taken from her home and forced into slavery. She was brought to North America and bought by the Wheatley family in Boston. They noticed her talent for writing and helped her learn to read and write. They also encouraged her to write poetry.

In 1773, Phillis traveled to London with the Wheatleys' son. There, she met important people who helped her publish her poems. Her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in London on September 1, 1773. This made her famous in both England and the American colonies. Famous people like George Washington admired her work. Later, another African-American poet, Jupiter Hammon, also praised her poems.

The Wheatley family freed Phillis shortly after her book was published. After the Wheatleys passed away, Phillis married John Peters, a grocer who faced financial struggles. They had three children, but sadly, all of them died young. Phillis Wheatley-Peters herself died at the young age of 31.

Contents

Phillis Wheatley's Early Life

Historians believe Phillis Wheatley was born in 1753 in West Africa. This was likely in what is now Gambia or Senegal. On July 11, 1761, she was brought to Boston, in the British Colony of Massachusetts. She arrived on a slave ship named The Phillis.

When she arrived in Boston, a wealthy merchant named John Wheatley bought her. She was bought as a slave for his wife, Susanna. The Wheatleys named her Phillis, after the ship she arrived on. They also gave her their last name, Wheatley. This was a common practice for enslaved people at the time.

The Wheatleys' 18-year-old daughter, Mary, was Phillis's first teacher. She taught Phillis how to read and write. Their son, Nathaniel, also helped her learn. John Wheatley was known for his modern ideas. His family gave Phillis a very special education. This was rare for anyone, especially for an enslaved person or a woman back then. By the age of 12, Phillis was reading Greek and Latin books. She also read difficult parts of the Bible. When she was 14, she wrote her first poem. It was called "To the University of Cambridge [Harvard], in New England."

The Wheatley family saw Phillis's amazing talent for writing. They supported her education and let their other enslaved workers handle the housework. The Wheatleys often showed off Phillis's skills to their friends and family. Phillis was greatly inspired by the writings of Alexander Pope, John Milton, Homer, Horace, and Virgil. She soon began to write her own poetry.

Phillis Wheatley's Later Life

In 1773, when she was 20, Phillis went to London with Nathaniel Wheatley. Part of the reason was for her health, as she had asthma. But the main reason was that Susanna Wheatley believed Phillis would have a better chance to publish her book of poems there.

In London, Phillis met important people. She had a meeting with Frederick Bull, who was the Lord Mayor of London. She also met other important British people. A meeting with King George III was planned, but Phillis had to return to Boston before it could happen. Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, became very interested in Phillis. She helped pay for the publication of Phillis's book of poems. The book was published in London in the summer of 1773. The Countess was ill, so they never met in person.

After her book was published, the Wheatleys freed Phillis by November 1773. Susanna Wheatley died in 1774, and John died in 1778. Soon after, Phillis met and married John Peters. He was a poor free black grocer. They lived in difficult conditions, and two of their babies died.

John Peters faced financial problems and was put in prison for debt in 1784. Phillis had a sick infant son to care for. She took a job working in a boarding house, doing hard work she had never done before. Phillis died on December 5, 1784, at the age of 31. Her infant son died soon after.

Other Writings by Phillis Wheatley

Phillis Wheatley wrote a letter to Reverend Samson Occom. In it, she praised his ideas that enslaved people should have their natural rights in America. Wheatley also wrote letters to the British helper John Thornton. Through her letters, Wheatley shared her thoughts and concerns with others.

In 1775, she sent a poem called "To His Excellency, George Washington" to the military general. The next year, Washington invited Wheatley to visit him. She went to his headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in March 1776. Thomas Paine later published her poem in the Pennsylvania Gazette in April 1776.

In 1779, Wheatley planned to publish a second book of poems. However, she could not find people to support her after she was freed. Publishers often needed people to promise to buy books beforehand. The American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) also made it hard to publish. Still, some of her poems meant for the second book were later printed in newspapers.

Phillis Wheatley's Poetry

In 1768, Wheatley wrote "To the King's Most Excellent Majesty." In this poem, she praised King George III for ending the Stamp Act. But while talking about freedom, Wheatley also quietly suggested freedom for enslaved people.

May George, beloved by all the nations round,

Live with heav’ns choicest constant blessings crown’d!

Great God, direct, and guard him from on high,

And from his head let ev’ry evil fly!

And may each clime with equal gladness see

A monarch’s smile can set his subjects free!

As the American Revolution grew stronger, Wheatley's writing began to focus on ideas of the American colonists who wanted independence.

In 1770, she wrote a poem honoring George Whitefield, a religious leader. Her poems often used Christian themes. Many were written for famous people. More than a third of her poems were elegies, which are poems for the dead. The rest were about religious, classical, or abstract ideas. She rarely wrote about her own life in her poems. One poem that touches on slavery is "On being brought from Africa to America":

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic dye."

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

Many colonists found it hard to believe that an African slave could write such "excellent" poetry. Phillis Wheatley had to prove she wrote her poems in court in 1772. A group of important Boston leaders questioned her. These included John Hancock and the governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson. They decided that she had indeed written the poems. They signed a statement saying so, which was put in the front of her book. Her book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in London in 1773. Publishers in Boston had refused to print it.

In London, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon and the Earl of Dartmouth helped Wheatley get her book published. Her poetry was reviewed in The London Magazine in 1773. The magazine published her poem "Hymn to the Morning." They wrote that her poems "display no astonishing power of genius." But they added, "when we consider them as the productions of a young untutored African... we cannot suppress our admiration." Her book was printed 11 times until 1816.

In 1778, the African-American poet Jupiter Hammon wrote a poem for Wheatley. Hammon thought Wheatley might be moving away from Christian ideas in her writing. So, his poem included Bible verses. He hoped it would encourage her to stay on a Christian path.

In 1838, a publisher in Boston named Isaac Knapp published some of Wheatley's poems. It also included poems by another enslaved poet, George Moses Horton. The book was called Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave. Also, Poems by a Slave.

Thomas Jefferson, in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, did not think much of her work. He wrote that black people had "no poetry." He said that while religion had produced a Phillis Wheatley, it could not produce a true poet.

How Phillis Wheatley Wrote

Phillis Wheatley believed poetry had great power. Her poems were not just copies of what she read. They showed her own ideas and beliefs.

Her writing style was thoughtful and calm. She often used three main ideas in her poems: Christianity, classical stories, and a special way of honoring the sun. The idea of honoring the sun came from her African heritage. She used many different words for the sun, like Aurora, Apollo, Phoebus, and Sol. Some scholars think the word "light" was important to her because it connected to her African past. She also referred to a "heavenly muse" in some poems, meaning the Christian God.

Wheatley often used ideas from ancient Greek and Roman stories. This made her work stand out from other poets of her time. For example, in her poem "To Maecenas," she used references to Maecenas to show the relationship between herself and her own helpers. She also mentioned Achilles, Patroclus, Homer, and Virgil.

Some experts believe Wheatley's use of classical ideas was a clever way to send messages to her educated, mostly white readers. They think she was quietly arguing for her own freedom and the freedom of other enslaved people.

Phillis Wheatley's Legacy

When Phillis Wheatley's book Poems on Various Subjects was published in 1773, she became "the most famous African on the face of the earth." The French writer Voltaire said that Wheatley proved black people could write poetry. John Paul Jones, a naval hero, asked someone to deliver his writings to "Phillis the African favorite of the Nine (muses) and Apollo." Many of America's founding fathers honored her. George Washington wrote to her, praising her "great poetical Talents."

Experts see her work as very important to African-American literature. She is honored as the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry. She was also the first to earn a living from her writing.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Phillis Wheatley as one of his 100 Greatest African Americans.

- Wheatley is honored in the Boston Women's Memorial. This is a sculpture in Boston, Massachusetts, created in 2003. It also features Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone.

- In 2012, Robert Morris University named a new building after Phillis Wheatley.

- Wheatley Hall at UMass Boston is also named for her.

Many places and organizations have been named after Phillis Wheatley. These include the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA in Washington, D.C., and the Phillis Wheatley High School in Houston, Texas. There is also a historic Phillis Wheatley School in Jensen Beach, Florida. A library branch in Columbia, South Carolina, which was the first to serve black citizens, is named for her. The Phillis Wheatley Elementary School, New Orleans, opened in 1954. Community centers in Greenville, South Carolina, and Minneapolis, Minnesota, also bear her name.

On July 16, 2019, a special blue plaque was put up in London. It honors Phillis Wheatley at the spot where her first book was published in 1773.

Wheatley is also the subject of a play by British-Nigerian writer Ade Solanke. It is called Phillis in London.

See also

In Spanish: Phillis Wheatley para niños

In Spanish: Phillis Wheatley para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |