John Hancock facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Hancock

|

|

|---|---|

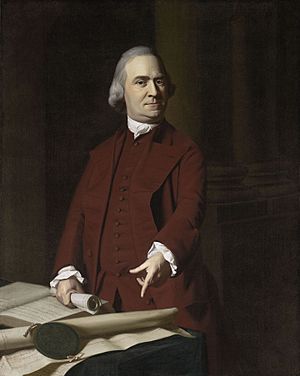

Portrait by John Singleton Copley, c. 1770–1772

|

|

| 1st and 3rd Governor of Massachusetts | |

| In office May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 |

|

| Lieutenant | Samuel Adams |

| Preceded by | James Bowdoin |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Adams |

| In office October 25, 1780 – January 29, 1785 |

|

| Lieutenant | Thomas Cushing |

| Preceded by | Office established (partly Thomas Gage as colonial governor) |

| Succeeded by | James Bowdoin |

| 4th and 13th President of the Continental Congress | |

| In office November 23, 1785 – June 5, 1786 |

|

| Preceded by | Richard Henry Lee |

| Succeeded by | Nathaniel Gorham |

| In office May 24, 1775 – October 31, 1777 |

|

| Preceded by | Peyton Randolph |

| Succeeded by | Henry Laurens |

| 1st President of Massachusetts Provincial Congress | |

| In office October 7, 1774 – May 2, 1775 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Warren |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 23, 1737 Braintree, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America (now Quincy) |

| Died | October 8, 1793 (aged 56) Hancock Manor, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Granary Burying Ground, Boston |

| Spouse |

Dorothy Quincy

(m. 1775) |

| Children | Lydia Henchman Hancock (1776–1777) John George Washington Hancock (1778–1787) |

| Relatives | Quincy political family |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

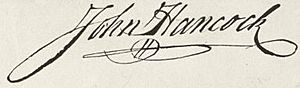

| Signature | |

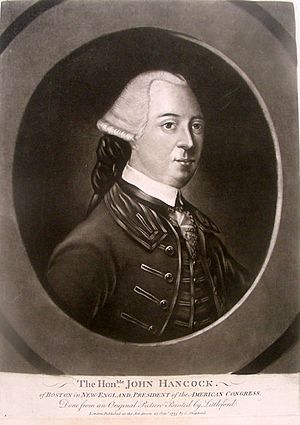

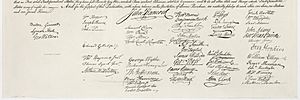

John Hancock (born January 23, 1737 – died October 8, 1793) was an important American leader. He played a big part in the American Revolutionary War. He was the very first person to sign the Declaration of Independence. Because of his famous signature, people in the United States sometimes say "John Hancock" when they mean "signature."

Contents

Early Life and Family

John Hancock was born in 1737 in a town called Braintree. This town is now known as Quincy, Massachusetts. His father was Colonel John Hancock Jr. His mother was Mary Hawke Thaxter.

When John was seven years old, his father passed away. He then went to live with his uncle, Thomas Hancock, and his aunt, Lydia Hancock.

Thomas Hancock was a very successful businessman in Boston. He owned a company called the House of Hancock. This company brought in goods from Britain and sent out things like rum and fish. Thomas Hancock became one of the richest people in Boston. He and Lydia lived in a big house called Hancock Manor. Since they had no children of their own, John's aunt and uncle became very important in his life.

Education and Business

John Hancock went to the Boston Latin School. After that, he studied at Harvard College. He graduated in 1754.

After college, John started working for his uncle's business. This was during the French and Indian War. His uncle had good connections with the governors of Massachusetts. This helped him get profitable contracts during the war. John learned a lot about business from his uncle. He was being prepared to take over the company one day. As his uncle's health got worse, John slowly took charge of the House of Hancock.

Starting in Politics

John Hancock began his political journey in Boston. He was helped by Samuel Adams, a powerful local politician. Even though they were close at first, their friendship later changed.

As problems grew between the colonists and Great Britain, Hancock used his wealth to support the colonists. This was in the 1760s.

The Liberty Incident

In 1768, British officials took Hancock's ship, the Liberty. They said he was smuggling goods. The ship was carrying wine at the time. People in Boston were very angry and rioted. Hancock was later found innocent. This event was one of many that led to the American Revolutionary War.

Important Political Roles

Hancock held many important jobs in Colonial America and the early United States of America. He was the president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1774 and 1775. He used his money to help America become independent. The British saw him as a very dangerous person.

Hancock was also the president of the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1777.

In 1780, Hancock led the meeting that created the Massachusetts Constitution. He became the first Governor of Massachusetts. He served nine terms as governor. He led Massachusetts through the end of the Revolutionary War and into a tough economic time after the war. He resigned as governor in 1785 because of his poor health.

Later Years and Passing

John Hancock's health was not good in his final years. He was mostly a leader in name only. He passed away in his bed on October 8, 1793, at the age of 56. His wife was by his side.

The acting governor, Samuel Adams, declared the day of Hancock's burial a state holiday. His funeral was very grand. It was one of the biggest funerals for an American at that time.

Personal Life

Hancock married his fiancée, Dorothy "Dolly" Quincy, on August 28, 1775. They had two children together. Sadly, neither of their children lived to be adults. Their daughter, Lydia, was born in 1776 and died when she was ten months old. Their son, John, was born in 1778. He died in 1787 after getting a head injury while ice skating.

Interesting Facts About John Hancock

- Before the American Revolution, John Hancock was one of the richest men in the Thirteen Colonies.

- People say that Hancock signed his name very large and clear. He wanted King George to be able to read it without his glasses!

- Hancock was considered for president in the 1789 U.S. presidential election. He did not try to win or even say he was interested. He only received four votes.

- In his later life, Hancock suffered from a painful condition called gout.

- The first full book about Hancock was not written until the 1900s.

Legacy and Remembrance

After he died, people didn't remember John Hancock as much. But in 1876, for the 100th birthday of American independence, people became interested in the Revolution again. Plaques honoring Hancock were put up in Boston. In 1896, a memorial was placed over his grave.

Many places and things in the United States are named after John Hancock.

- The U.S. Navy has named ships USS Hancock and USS John Hancock.

- Ten states have a Hancock County named for him.

- Other places named after him include Hancock, Massachusetts; Hancock, Michigan; Hancock, New Hampshire; and Hancock, New York.

- Mount Hancock in New Hampshire is also named for him.

- The John Hancock Financial company, started in Boston in 1862, is named after him.

- This company's name was also given to the John Hancock Tower in Boston and the John Hancock Center in Chicago.

- Hancock was a founding member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1780.

Images for kids

-

Hancock House, a copy of Hancock Manor in Boston, is a museum in New York.

See also

In Spanish: John Hancock para niños

In Spanish: John Hancock para niños

- List of richest Americans in history

- Signing of the United States Declaration of Independence

- Memorial to the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |