Signing of the United States Declaration of Independence facts for kids

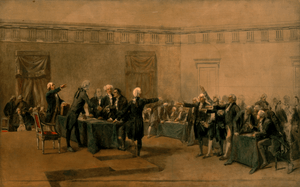

John Trumbull's 1819 painting, Declaration of Independence, shows the five-man drafting committee presenting their work to the Second Continental Congress

|

|

| Date | August 2, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Independence Hall |

| Location | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Participants | Delegates to the Second Continental Congress |

The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence was a very important event in American history. It mostly happened on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia. This building is now known as Independence Hall.

Fifty-six representatives, called delegates, from the 13 American colonies signed the Declaration. These delegates were part of the Second Continental Congress. On July 4, 1776, 12 of the 13 colonies voted to approve the Declaration of Independence. The delegates from New York did not vote at that time because they were waiting for instructions from their home state.

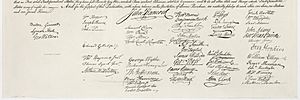

The Declaration announced that the 13 colonies were now "free and independent States." This meant they were no longer colonies of the Kingdom of Great Britain and were no longer part of the British Empire. The names of the signers are grouped by their state. The states are listed from south to north. John Hancock, who was the President of the Continental Congress, signed first.

Even though the Declaration was approved on July 4, the exact date it was signed has been debated for a long time. Most historians now agree that it was signed on August 2, 1776. This was nearly a month after it was first approved.

Contents

When Was the Declaration Signed?

The Second Continental Congress officially adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Twelve of the 13 colonies voted for it, and New York did not vote yet.

The date of the signing has been a big discussion point. Important figures like Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams all wrote that it was signed on July 4. The official signed copy of the Declaration also has the date July 4 on it. The Journals of Congress, which are the official records, also say it was signed on July 4.

However, in 1796, one of the signers, Thomas McKean, said that no one signed it on July 4. He pointed out that some signers were not even there on that day. Some were not even elected to Congress until after July 4. He wrote, "No person signed it on that day nor for many days after."

His claim was supported when the Secret Journals of Congress were published in 1821. These journals had two new entries about the Declaration.

- On July 15, New York's delegates finally got permission to agree to the Declaration.

- The entry for July 19 said: "Resolved That the Declaration passed on the 4th be fairly engrossed on parchment... & that the same when engrossed be signed by every member of Congress." This meant a clean, handwritten copy should be made and signed.

- The entry for August 2 said: "The declaration of Independence being engrossed & compared at the table was signed by the Members."

In 1884, historian Mellen Chamberlain argued that these entries showed the famous signed Declaration was created after July 19. He believed it was not signed by Congress until August 2. Later research has shown that many signers were not in Congress on July 4. Some delegates might have even signed after August 2.

Even though Jefferson and Adams always believed the signing was on July 4, most historians now agree with David McCullough. He wrote that a scene with all delegates present on July 4 "never occurred at Philadelphia."

In 1986, legal historian Wilfred Ritz suggested that about 34 delegates signed on July 4. The others signed on or after August 2. Ritz believed that the official copy was indeed signed on July 4, as Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin said. He thought it was unlikely all three were wrong. He also believed that McKean's statements were not completely accurate.

Ritz argued that the July 19 resolution did not ask for a new document. Instead, it asked for the existing one to get a new title. This was needed after New York joined the other 12 states in declaring independence. He thought "signed by every member of Congress" meant that delegates who had not signed on July 4 now had to do so.

Who Signed the Declaration?

Fifty-six delegates eventually signed the Declaration of Independence. Here is a list of their names, grouped by the states they represented:

Interesting Facts About the Signers

About 50 delegates were in Congress when the vote for independence happened in early July 1776. However, eight of them never signed the Declaration. These included John Alsop, George Clinton, John Dickinson, Charles Humphreys, Robert R. Livingston, John Rogers, Thomas Willing, and Henry Wisner.

- Clinton, Livingston, and Wisner were away on other duties when the signing happened.

- Willing and Humphreys voted against independence. They were replaced in the Pennsylvania group before the August 2 signing.

- Rogers had voted for independence but was no longer a delegate on August 2.

- Alsop wanted to stay friends with Great Britain, so he resigned instead of signing.

- Dickinson refused to sign because he thought it was too early for independence. But he stayed in Congress.

- Interestingly, George Read had voted against independence, and Robert Morris had not voted at all. Yet, both of them signed the Declaration.

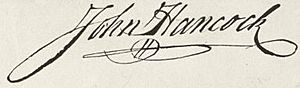

The most famous signature on the Declaration is that of John Hancock. He was the President of Congress and likely signed first. Hancock's large and fancy signature became very well-known. In the United States, "John Hancock" is now a common way to say "signature."

Two future presidents, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, were also among the signers. The youngest signer was Edward Rutledge, who was 26 years old. The oldest signer was Benjamin Franklin, who was 70 years old.

Some delegates were away when the Declaration was discussed, like William Hooper and Samuel Chase. But they came back to Congress to sign on August 2. Other delegates were there for the debate but signed after August 2. These included Lewis Morris, Oliver Wolcott, Thomas McKean, and possibly Elbridge Gerry. Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe were in Virginia during July and August. They returned to Congress and signed the Declaration later, probably in September and October.

New delegates who joined Congress were also allowed to sign. Eight men signed the Declaration who did not become members of Congress until after July 4. These were Matthew Thornton, William Williams, Benjamin Rush, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, George Ross, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton. Matthew Thornton did not join Congress until November. When he signed, there was no space next to the other New Hampshire delegates, so he put his signature at the very end of the document.

The first published version of the Declaration was called the Dunlap broadside. Only the names of Congress President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson were on it, and they were printed, not signed. The public did not find out who had signed the official copy until January 18, 1777. That's when Congress ordered an "authenticated copy" to be sent to each of the 13 states, including the names of all the signers. This copy is known as the Goddard Broadside. It was the first to list all the signers, except for Thomas McKean. He might have signed after the Goddard Broadside was published. Charles Thomson, the Congress Secretary, did not sign the official copy of the Declaration, and his name is not on the Goddard Broadside, even though it was on the Dunlap broadside.

Famous Stories and Legends

Many stories and legends about the signing of the Declaration appeared years later. By then, the document had become a very important national symbol.

In one famous story, John Hancock supposedly said that Congress, after signing the Declaration, must now "all hang together." Benjamin Franklin is said to have replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." This quote means they had to stick together to succeed, or they would all be punished separately by the British. The earliest known version of this quote was printed in a London humor magazine in 1837.

See also

In Spanish: Firma de la Declaración de Independencia de los Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Firma de la Declaración de Independencia de los Estados Unidos para niños

- Memorial to the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence

- Signing of the United States Constitution

Images for kids

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |