John Witherspoon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Witherspoon

|

|

|---|---|

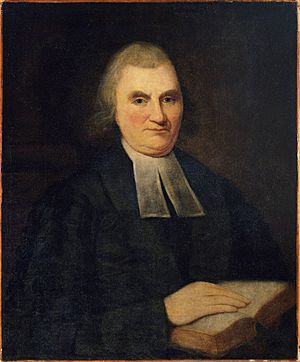

Portrait by Charles Wilson Peale, c. 1790

|

|

| 6th President of Princeton University | |

| In office 1768–1794 |

|

| Preceded by | John Blair (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Stanhope Smith |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 5, 1723 Beith, North Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Died | November 15, 1794 (aged 71) Near Princeton, New Jersey, US |

| Resting place | Princeton Cemetery |

| Nationality | American/Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Clergyman and theologian |

| Signature | |

John Witherspoon (born February 5, 1723 – died November 15, 1794) was an important Scottish American Presbyterian minister and teacher. He was also a farmer and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon became a very important person in shaping the early United States. He was the president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) from 1768 to 1794.

Witherspoon was active in politics. He represented New Jersey in the Second Continental Congress. He also signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. He was the only active church leader and college president to sign this important document. Later, he signed the Articles of Confederation and supported the Constitution of the United States.

In 1789, he led the first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

Contents

Early Life in Scotland

John Witherspoon was born in Yester, Scotland. He was the oldest child of Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon and Anne Walker. He went to the Haddington Grammar School. In 1739, he earned a Master of Arts degree from the University of Edinburgh. He continued his studies there to become a minister. In 1764, he received an honorary doctorate degree from the University of St Andrews.

Witherspoon was a strong Protestant and believed in a republican government. He was against the Roman Catholic uprising of 1745–46. After a battle, he was briefly held prisoner at Doune Castle. This experience affected his health for a long time.

He became a Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) minister in Beith, Ayrshire, from 1745 to 1758. There, he married Elizabeth Montgomery. They had ten children, but only five lived to be adults.

From 1758 to 1768, he was a minister in Laigh Kirk, Paisley (Low Kirk). He became well-known in the Church for opposing the "Moderate Party." During his time as a minister, he wrote several important books on religion.

Leading Princeton University

Benjamin Rush and Richard Stockton convinced John Witherspoon to become the president of the College of New Jersey. He had turned down the offer once before. In 1768, Witherspoon and his family moved to New Jersey.

At 45 years old, he became the sixth president of the college. This school is now known as Princeton University. When he arrived, the college was in debt. The teaching was not strong, and the library needed many more books. Witherspoon immediately started raising money. He also added 300 of his own books to the library. He bought scientific tools, maps, and a globe.

Witherspoon made many changes to the college. He based the school's plan and courses on those used at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. He also made the entrance requirements stricter. This helped the college compete with schools like Harvard and Yale.

Witherspoon taught classes in public speaking, history, and religion. His most important course was moral philosophy, which was required for all students. He believed that understanding moral philosophy was key for future ministers, lawyers, and government leaders. He was a strong but fair leader and was well-liked by students and teachers.

Before coming to Princeton, Witherspoon was a leading Presbyterian minister in Scotland. Since the college mainly trained ministers at that time, he became a major leader in the early Presbyterian Church in America. He also helped start Nassau Presbyterian Church in Princeton.

Witherspoon changed the college from mainly training ministers to preparing leaders for a new country. Many of his students became important figures in the new nation. These included James Madison, Aaron Burr, and Philip Freneau. Among his students, 37 became judges, 10 became Cabinet officers, and many served in Congress.

Role in the Revolutionary War

Witherspoon had long been cautious of the power of the British Crown. He saw the British government gaining too much control over the colonies. He also worried about the British church leaders gaining more power over American churches. This upset him greatly, as he remembered similar struggles in Scotland.

Soon, Witherspoon supported the American Revolution. In early 1774, he joined the New Jersey Committee of Correspondence. In 1776, he gave a famous sermon called "The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Men." He was then chosen to represent New Jersey in the Continental Congress. In Congress, he became a chaplain. In July 1776, he voted for independence. When some said the country was not ready, he famously replied that it "was not only ripe for the measure, but in danger of rotting for the want of it."

Witherspoon served in Congress from June 1777 to November 1784. He was a very influential and hardworking member. He served on many committees, including those for peace and public affairs. He helped write the Articles of Confederation. He also helped set up the government departments. He worked to stop the printing of too much paper money. He also served twice in the New Jersey Legislature. He strongly supported the Constitution of the United States during the debates to approve it.

In November 1777, as American soldiers approached, Witherspoon closed the College of New Jersey. The main building, Nassau Hall, was badly damaged. His personal papers and notes were lost. After the war, Witherspoon worked hard to rebuild the college. This caused him many personal and financial problems. In 1780, he served a one-year term in the New Jersey Legislative Council. At 68, he married a 24-year-old widow, and they had two more children.

Death and Burial

Witherspoon had eye injuries and became blind by 1792. He died in 1794 on his farm, Tusculum, near Princeton. He is buried in Princeton Cemetery. Records show that at his death, he owned "two slaves."

Family Life

John Witherspoon and his wife, Elizabeth Montgomery, had 10 children. Only five of them lived to move to America with their parents. Their oldest son, James, graduated from Princeton in 1770. He joined the Continental Army and was killed in battle in 1777. Their next son, John, became a doctor and was lost at sea in 1795. David, the youngest son, became a lawyer. Their oldest daughter, Anna, married Reverend Samuel Stanhope Smith, who later became president of Princeton. Their youngest daughter, Frances, married Dr. David Ramsay, a delegate to the Continental Congress.

His Ideas and Beliefs

John Witherspoon's most lasting contribution was introducing a way of thinking called Scottish common sense realism. This idea focused on common sense and practical ideas.

At Princeton, Witherspoon changed the moral philosophy courses. He made the college more connected to the wider world of ideas. Witherspoon believed in Christian values. His approach to public morality was influenced by Scottish philosophers. He thought that moral judgment should be studied like a science. He believed that leaders should be virtuous, like in the old Roman Republic. He also told his students to read modern philosophers like Machiavelli and Montesquieu.

He argued that good behavior could be learned through developing a "moral sense." This was an ethical guide given by God to all people. It could be developed through religious education or social interaction. Witherspoon saw morality as having two parts: spiritual and worldly. He believed that government owed more to worldly moral laws than to revealed Christianity.

In his lectures at Princeton, Witherspoon taught about the right to resist unfair government. He also talked about checks and balances within government. He greatly influenced his student James Madison, who later helped shape the United States Constitution.

Witherspoon believed that people could not be truly moral without religion. He thought that public religion was necessary to keep public morals strong. However, he also believed that non-Christian societies could have good morals. This was because he thought moral laws could be found in nature. Witherspoon taught that all people, Christian or not, could be good. But he also believed that Christianity was the only way to personal salvation.

Witherspoon owned slaves. He also spoke against the immediate end of slavery. However, in his lectures, he spoke about treating workers and servants (including slaves) kindly.

This relationship comes from the differences God allows between people. Some are smarter, some have more property from their hard work, and some choose to work for others for money.

Let's look at (1.) How far this control goes. (2.) The duties of each side. For the first, it seems the master only has a right to the servant's work for a limited time, or at most for life. He has no right to take a life or make it unbearable with too much work. So, the servant keeps all their other natural rights. The old practice of making war prisoners slaves was wrong and cruel. Even if we thought those who started an unfair war deserved to be slaves, this wouldn't be true for everyone who fought on their side. Also, doing it once would allow it anytime. Those who defended their country when it was unfairly attacked could be taken as well. This practice was also unwise, as slaves are never as good or loyal as those who work for a set time by agreement. [John Witherspoon, Lectures on Moral Philosophy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1912), pp. 85-86.]

Many of the American Founding Fathers, including Dr. Witherspoon, thought slavery would naturally disappear over time. Because of this, Reverend Witherspoon supported "gradual emancipation" of slaves.

In 1790, President Witherspoon was part of a committee in the New Jersey Legislature about ending slavery. He advised against immediate action. He said the law already stopped importing slaves and encouraged owners to free them voluntarily. He suggested that the state could pass a law that all slaves born after a certain date would be free at a certain age (like 28 years old, as in Pennsylvania). However, he believed that society in America and the idea of freedom were progressing so much that there would be no slaves in America in 28 years anyway. He felt that rushing things might do more harm than good. [John Witherspoon, Lectures on Moral Philosophy (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 1912), p. 74]

His Legacy

Witherspoon is remembered for his strong beliefs and his role in shaping early America. He was a key figure in the Reformed tradition of Christianity. He believed that religious truths could be understood through reason. His goal as a minister was to explain traditional Scottish Presbyterian beliefs.

Statues

- Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

- Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia

- University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, Scotland, United Kingdom

- Doctor John Witherspoon, Washington, D.C.

Buildings

- Witherspoon Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey

- Witherspoon Building, in Market East in Philadelphia

- The former Witherspoon Street School for Colored Children, Princeton, New Jersey

- The former John Witherspoon Middle School, Princeton, New Jersey. In 2021, the school board voted to remove his name because he owned slaves and opposed immediate abolition. The school is now called Princeton Unified Middle School.

Memberships

Witherspoon was chosen to be a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1789.

Other Honors

- John Witherspoon College, a Christian college in Rapid City, South Dakota

- Witherspoon Institute, a research center in Princeton, New Jersey

- Witherspoon Society, a group within the Presbyterian Church (USA)

- Witherspoon Street, found in Princeton, New Jersey; Louisville, Kentucky; and Paisley, Scotland

- SS John Witherspoon, a Liberty ship during World War II. It was sunk in 1942.

- He was shown in the musical 1776, about the Declaration of Independence.

See also

Images for kids

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |