George Wythe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

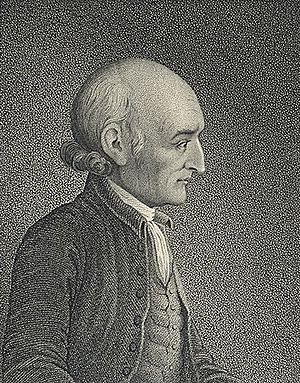

George Wythe

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Delegate from Virginia to the Continental Congress |

|

| In office June 1775 – June 1776 |

|

| Attorney General of Virginia | |

| In office January 29, 1754 – February 10, 1755 |

|

| Preceded by | Peyton Randolph |

| Succeeded by | Peyton Randolph |

| In office November 22, 1766 – June 11, 1767 |

|

| Preceded by | Peyton Randolph |

| Succeeded by | John Randolph |

| Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

| In office 1777–1778 |

|

| Preceded by | Edmund Pendleton |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Harrison V |

| Mayor of Williamsburg, Virginia | |

| In office 1768–1769 |

|

| Preceded by | James Cocke |

| Succeeded by | John Blair Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1726 Chesterville, Virginia, British America |

| Died | June 8, 1806 (aged 79–80) Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. John's Episcopal Church |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Education | College of William and Mary (BA) |

| Signature | |

George Wythe (pronounced "with"; 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an important American leader. He was a teacher, a legal expert, and a judge. Wythe is known as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was the first person from Virginia to sign the United States Declaration of Independence.

Wythe represented Virginia in the Continental Congress and the Philadelphia Convention. He helped create the rules for the convention. He left before signing the U.S. Constitution to care for his sick wife. Later, he helped Virginia approve the Constitution. Wythe also taught and guided many future American leaders. These included Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Henry Clay.

Wythe came from a wealthy family in Virginia. He became a lawyer in Williamsburg, Virginia. He joined the House of Burgesses in 1754. There, he helped manage money for defense during the French and Indian War. He was against the Stamp Act of 1765 and other British taxes. He also helped design the Seal of Virginia. Wythe served as a judge for most of his life. He was also a respected law professor at the College of William & Mary. He was very close to Jefferson and left him his large book collection. Wythe became concerned about slavery. He freed all his enslaved people after the American Revolution.

Contents

Early Life and Education

George Wythe was born in 1726. His birthplace was Chesterville, a family farm in what is now Hampton, Virginia. His mother, Margaret Walker, loved learning. She passed this love on to her son. Wythe's great-grandfather, George Keith, was a Quaker minister. He was one of the first people to speak out against slavery.

After his father died, Wythe likely went to grammar school in Williamsburg. Then, he began studying law with his uncle, Stephen Dewey.

Career Beginnings

Wythe became a lawyer in 1746. This was the same year his mother passed away. He then moved to Spotsylvania County to start his law practice. In 1747, he married Ann Lewis. Sadly, she died in 1748. Wythe then returned to Williamsburg. He focused his life on law and learning. His personal motto was "Upright in prosperity and perils."

Colonial Politics and Mentoring

In 1748, Wythe got his first government job. He became a clerk for two important committees in the House of Burgesses. He also continued to practice law. In 1750, Wythe was elected as an alderman in Williamsburg. He briefly served as the king's attorney general in 1754–1755.

In 1754, Wythe became a representative for Williamsburg in the House of Burgesses. In 1755, his older brother, Thomas, died. Wythe inherited the family farm, Chesterville. He also took his brother's place on the Elizabeth City County court. Wythe likely stayed in Williamsburg. He married Elizabeth Taliaferro. Her father built a house for them in Williamsburg. This house is now known as the Wythe House.

Wythe served as Williamsburg's delegate until 1755. He later became a clerk for several committees. In 1759, the College of William & Mary elected Wythe as its representative. He helped manage money for defense during the French and Indian War. From 1761 to 1767, Wythe represented Elizabeth City County.

Wythe was known for being modest and quiet. But he became a strong opponent of the Stamp Act of 1765. He also opposed other British taxes on the colonies. Wythe was good friends with Governors Francis Fauquier and Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt. He was also known for his honesty. In 1762, Wythe began supervising the legal training of Thomas Jefferson. This mentorship had a huge impact on both their lives.

Law Practice and Public Service

Wythe continued his successful law practice with Jefferson's help. In 1767, Wythe introduced Jefferson to the General Court. Jefferson then became a clerk for the House of Burgesses. Wythe also ordered important legal books and journals from London.

Wythe's social standing was high. He was elected mayor of Williamsburg from 1768 to 1769. He also became a vestryman at Bruton Parish Church in 1769.

In 1768, Governor Botetourt arrived in Virginia. He was the first governor in 60 years to rule the colony in person. Botetourt dissolved the House of Burgesses in 1769. This happened after protests in Massachusetts against the Townshend Acts. But Wythe helped the delegates publish a protest resolution before they received the order. The burgesses then met at the Raleigh Tavern. There, they passed the Virginia Nonimportation Resolutions.

Road to Revolution

The next royal governor, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, caused more tension. Dunmore arrived in Williamsburg in 1771. He tried to govern without the burgesses. But money problems forced him to call the assembly in 1773. Delegates worried that people accused in the Gaspee burning could be tried in England. When they formed a Committee of Correspondence, Dunmore postponed the assembly.

Parliament passed the Tea Act in May 1773. In December, the Sons of Liberty held the Boston Tea Party. Dunmore tried to gather the delegates again in May 1774. On May 24, 1774, the House of Burgesses declared June 1 a day of fasting and prayer. Wythe signed and posted this resolution. Dunmore was angry and dissolved the assembly. The delegates then met at the Raleigh Tavern. They met again in Richmond in March.

Wythe attended the Second Virginia Convention as Williamsburg's representative. This meeting was at St. John's Episcopal Church. Patrick Henry gave his famous "Give me liberty, or give me death!" speech. The delegates agreed to form a militia. This led Dunmore to try and remove military supplies from Williamsburg. Wythe joined the militia right away.

On May 10, 1775, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia. Wythe was chosen as Virginia's delegate. He replaced George Washington, who took command of the Continental Army. George and Elizabeth Wythe moved to Philadelphia. By October, Jefferson had rejoined Congress. Wythe took on many tasks related to the military and money. He also helped convince New Jersey to stay united with the other colonies.

By the summer of 1776, war seemed unavoidable. Wythe supported the resolution for independence that Jefferson had written. His fellow Virginia delegates respected him greatly. They left the first space open for him when they signed the Declaration of Independence. Wythe signed the Declaration of Independence when he returned to Philadelphia in September. The signers' names were kept secret until January. This was because signing was an act of treason.

Supporting independence came at a cost for Wythe. British raiding parties damaged plantations and settlements in Virginia. In January 1781, Benedict Arnold led British raiders. They forced Jefferson to flee Richmond. Fires burned the new state capital and destroyed many records. Wythe's own Chesterville farm was damaged. During the Yorktown campaign, American and French troops camped in Williamsburg. Count Rochambeau even stayed in the George Wythe house.

Founding the Nation

Wythe quickly returned to Virginia from Philadelphia. On June 23, 1776, he began helping Virginia set up its new state government. Wythe served on a committee with George Mason. They designed the Seal of Virginia. It has the motto Sic Semper Tyrannis, which means "Thus always to tyrants." This seal is still used today.

Wythe's most important work for the new state government happened that winter. He served on a committee with Jefferson and Edmund Pendleton. They worked to revise and organize Virginia's laws. They also helped create the new state court system. Many of their ideas, like religious freedom and public education, became important in the new republic. Wythe also replaced Pendleton as speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates from 1777–1778.

Wythe also helped establish the new nation. In 1787, Wythe was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. He, Alexander Hamilton, and Charles Pinckney served on the committee that set the convention's rules. Wythe left Philadelphia in early June to care for his sick wife. The next year, Wythe and John Blair represented York County at the Virginia Ratifying Convention. Wythe led many discussions. He spoke strongly for approving the Constitution.

Teacher and Mentor

Wythe's teaching career began in 1761. He was appointed to the Board of Visitors of the College of William & Mary. For over twenty years, Wythe taught many law students. His most famous students included future presidents Jefferson and James Monroe. Other notable students were future Chief Justice John Marshall and future Associate Justice Bushrod Washington. Wythe was skilled in Latin and Greek. He loved books and learning.

He often taught students individually. Especially after his wife Elizabeth died in 1787, some students lived at Wythe's home. They received daily lessons in classical languages, political ideas, and law. Wythe remained closest to Jefferson. They worked and wrote to each other for decades. They read many different kinds of books together.

In 1779, Governor Jefferson made Wythe the first law professor in the United States. Wythe taught using lectures based on important legal books. He also used practical methods like mock trials and mock legislative sessions. These methods are still used today. Wythe resigned from the college in 1789. He moved to Richmond to focus on his judicial duties.

In Richmond, Wythe continued to learn. He even started learning Hebrew. One of his last students, William Munford, called Wythe "one of the most remarkable men I ever knew." He remembered Wythe's advice: "Don't skim it; read deeply, and ponder what you read." St. George Tucker, his former student, took over as the college's law professor. In 1920, the college's law school was named after Wythe and Marshall.

Virginia Judge

Wythe served as a judge in Elizabeth City County during colonial times. But his reputation grew from his judicial service after Virginia became a state. He drafted an oath for admiralty judges. It said judges should "do equal right to all manner of people... without respect to persons." He also designed the chancery court seal. It showed the punishment of a Persian judge who took a bribe.

In 1777, Wythe became one of three judges on the new High Court of Chancery. He worked to develop this area of law for the rest of his life. Wythe disliked lawyers who made cases last a long time. This caused high costs for the people involved. In 1788, Wythe became the sole judge of Virginia's Chancery Court. He refused promotions to the Supreme Court of Appeals.

In 1782, Wythe wrote an opinion in Commonwealth v. Caton. He supported the idea that courts could review laws made by the legislature. This was an early example of judicial review. It was similar to Justice Marshall's later decision in Marbury v. Madison. Wythe said the court had the right to tell the legislature, "here is the limit of your authority."

However, Wythe's decisions were often changed or overturned by the appeals court. This was especially true after his former student Spencer Roane joined the court in 1794. Wythe published his case analyses and appellate decisions. One of his famous decisions, Page v. Pendleton, upheld a federal peace treaty. It required debts to British merchants to be paid. This was despite a Virginia law allowing payment in cheaper paper money.

Views on Slavery

Wythe became increasingly against slavery. He freed all his enslaved people after the American Revolution. In 1785, Jefferson confirmed that Wythe's feelings against slavery were very strong. In the years after the war, many Virginians freed enslaved people. The number of free black people in Virginia grew from less than 1% to almost 10% by 1810. However, new, stricter laws about slavery also developed.

In 1798, Virginia lawmakers made it illegal for members of anti-slavery groups to serve on juries in freedom lawsuits. This likely affected Wythe as a judge. In 1800, Governor James Monroe called out troops to stop a rebellion led by Gabriel Prosser near Richmond. Thirty-five enslaved people were executed. In 1806, the year Wythe died, a law passed requiring freed enslaved people to leave the state within 12 months.

Manumissions

When Wythe's wife Elizabeth died in 1787, he returned some enslaved people to her relatives. On August 20, 1787, Wythe filed papers to free Lydia Broadnax. She had been his housemaid and cook for a long time. Four years later, Lydia moved with Wythe to Richmond. A young mixed-race boy named Michael Brown, born free in 1790, also lived in Wythe's home. Wythe took an interest in Brown. He taught him Greek and shared his library. In 1797, Wythe also freed Benjamin, another adult enslaved person. Wythe included Benjamin in his 1803 will. He also left money for Brown's education.

Judicial Decisions on Slavery

For years, Wythe followed Virginia law that treated enslaved people as property. Slavery cases often went to chancery courts because there were no other legal solutions. Wythe wrote two legal opinions that tried to move Virginia away from its slave-based system.

Wythe and Pendleton both ruled in favor of freeing enslaved people in the case Pleasants v. Pleasants. This case was about a Quaker's will from 1771. It intended to free enslaved people before Virginia made it legal to do so in 1782. The decision was appealed. In 1799, the appellate court changed Wythe's decision. They said that children born to enslaved parents would not be free until they repaid their owners' costs.

In one of Wythe's last cases, Hudgins v. Wright (1806), Wythe tried to end slavery through his judicial interpretation. Jackey Wright, an enslaved woman, sued for freedom for herself and her two children. She claimed they were descended from American Indians. At this time, Indians were considered free in Virginia. Wythe ruled in favor of Wright. He found that the family showed only Indian and white ancestry. He also believed that "all men were presumptively free in Virginia" because of the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights.

When Hudgins appealed after Wythe's death, the Virginia Supreme Court upheld Wythe's decision to free Wright. However, they did so on limited grounds. They did not agree that the Declaration of Rights applied to black people.

Legacy and Honors

In 1790, the College of William & Mary gave Wythe an honorary LL.D. degree.

In his will, Wythe left his large book collection to Thomas Jefferson. This collection later became part of the Library of Congress. Jefferson praised Wythe as "my ancient master, my earliest and best friend." He said Wythe gave him the most helpful first impressions in his life.

Many places are named in Wythe's honor:

- Wythe's home in Williamsburg, Virginia, is next to Bruton Parish Church. It is now a museum called the Wythe House.

- Wythe County, Virginia, and its county seat Wytheville are named for him.

- The Wythe district in Hampton, Virginia, is also named after him.

- Several public schools in Virginia bear his name.

- The Marshall-Wythe School of Law at the College of William & Mary.

- George Wythe University in Salt Lake City, Utah.

- The World War II Liberty Ship SS George Wythe.

Images for kids

-

Thomas Jefferson's notes on Wythe's biography, 1820

-

Will of George Wythe, 1806, leaving books to Thomas Jefferson

See also

In Spanish: George Wythe para niños

In Spanish: George Wythe para niños

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |