Benjamin Harrison V facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benjamin Harrison V

|

|

|---|---|

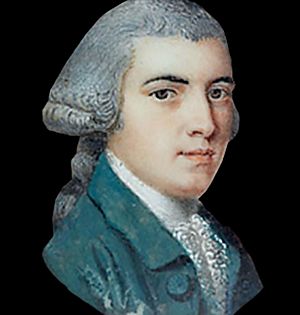

Miniature portrait, 18th century, unknown artist

|

|

| 5th Governor of Virginia | |

| In office December 1, 1781 – December 1, 1784 |

|

| Preceded by | Thomas Nelson Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Henry |

| Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates | |

| In office May 7, 1781 – December 1, 1781 |

|

| Preceded by | Richard Henry Lee |

| Succeeded by | John Tyler Sr. |

| In office May 4, 1778 – March 1, 1781 |

|

| Preceded by | George Wythe |

| Succeeded by | Richard Henry Lee |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Charles City County |

|

| In office May 5, 1777 – December 1, 1781 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel Harwood |

| Succeeded by | William Green Munford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 5, 1726 Charles City County, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | April 24, 1791 (aged 65) Charles City County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Berkeley Plantation, Charles City County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Bassett

(m. 1748) |

| Children |

|

| Parents | Benjamin Harrison IV Anne Carter |

| Alma mater | College of William and Mary |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

Benjamin Harrison V (born April 5, 1726 – died April 24, 1791) was an important American leader. He was a planter (someone who owned a large farm), a merchant, and a politician. He served in the government of colonial Virginia, just like his family members before him. Benjamin Harrison V was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He signed the Continental Association and the United States Declaration of Independence. He also served as Virginia's governor from 1781 to 1784.

He was born into the Harrison family of Virginia at their home, the Berkeley Plantation. He spent about 30 years serving in Virginia's government, representing different counties. Harrison was one of the first patriots to speak out against the rules that King George III and the British Parliament placed on the American colonies. These rules led to the American Revolution. He owned enslaved people. In 1772, he joined a group asking the king to stop the slave trade.

As a delegate to the Continental Congress, Harrison helped lead the final discussions about the Declaration of Independence. He signed it in 1776. The Declaration included a key idea for the United States: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Harrison became Virginia's fifth governor. His time as governor was tough because the state's money was almost gone after the Revolutionary War. Later, he returned to the Virginia House for two more terms. In 1788, he voted against the U.S. Constitution because it did not include a bill of rights. Two of his descendants later became U.S. presidents: his son William Henry Harrison and his great-grandson Benjamin Harrison.

Contents

Family Life

His Parents and Siblings

Benjamin Harrison V was born on April 5, 1726, in Charles City County, Virginia. He was the oldest of ten children. His parents were Benjamin Harrison IV and Anne Carter. Anne's father was Robert Carter I. The first Benjamin Harrison came to the colonies around 1630. By 1633, he started a family tradition of public service. Benjamin II and Benjamin III also served in the Virginia government.

Benjamin IV and Anne built the family's main house at Berkeley Plantation. Benjamin IV served as a judge and represented Charles City County in the Virginia government. Historians added the Roman numerals (like V) to their names later to tell them apart.

When he was young, Benjamin V was "tall and strongly built." He studied for a year or two at the College of William & Mary. His brother Carter Henry became a leader in Cumberland County. His brother Nathaniel was elected to the Virginia government. His brother Henry fought in the French and Indian War. His brother Charles became a general in the Continental Army.

Inheritance and Enslaved People

On July 12, 1745, Benjamin V's father died. Benjamin V inherited most of his father's property. This included Berkeley and other farms, plus thousands of acres of land. He also inherited a fishing business and a mill. Along with the property, he took ownership of many enslaved people. His brothers and sisters inherited other farms and enslaved people. His father decided not to leave everything to the oldest son, which was a common tradition.

The Harrison family owned many enslaved people, sometimes as many as 80 to 100. Benjamin V's father wanted to keep enslaved families together when dividing his property. Like all large farm owners, the Harrisons depended on enslaved people to work their land.

Marriage and Children

In 1748, Harrison married Elizabeth Bassett from New Kent County. She was the daughter of Colonel William Bassett. Harrison and Elizabeth had eight children during their 40 years of marriage.

Their oldest daughter, Lucy Bassett (1749–1809), married Peyton Randolph. Another daughter, Anne Bassett (1753–1821), married David Coupland. Their oldest son was Benjamin Harrison VI (1755–1799). He served in the Virginia government but died young. Another son was Carter Bassett Harrison (c.1756–1808). He served in the Virginia government and the U.S. House of Representatives.

Their youngest child was General William Henry Harrison (1773–1841). He became a delegate for the Northwest Territory and governor of the Indiana Territory. In 1840, William Henry became president but died just one month into his term. His grandson, Benjamin Harrison (1833–1901), was a general during the American Civil War. He later served in the U.S. Senate and was elected president in 1888.

Serving Virginia

Early Political Career

In 1749, Harrison followed his father's path and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. He was too young to take his seat right away, so he started in 1752. He represented different counties:

- 1752–1761 – Surry County

- 1766–1781 – Charles City County

- 1785–1786 – Surry County

- 1787–1790 – Charles City County

In 1752, Harrison joined a committee that argued with King George and the British Parliament. They were upset about a tax the governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, placed on land. This argument was an early sign of the "no taxation without representation" issue that led to the American Revolution. Harrison helped write a complaint to the king. A compromise was reached, but the British still said the colonists' government had little power.

Harrison again opposed Britain when it passed the Townshend Acts. These acts said Parliament had the right to tax the colonies. In 1768, he helped write a response for Virginia. It said that British citizens should only be taxed by their own elected representatives. The Townshend Acts were eventually canceled, except for the tax on tea.

In 1770, Harrison signed the Virginia Association. This was a group of Virginia lawmakers and merchants who agreed to stop buying British goods until the tea tax was removed. He also supported a law saying Parliament's laws were illegal without the colonists' agreement. Harrison also served as a judge in Charles City County. In 1771, he helped buy a building for the city of Williamsburg to use as a courthouse. In 1772, Harrison and Thomas Jefferson were among a group who asked the king to stop bringing enslaved people from Africa. The king refused this request.

Delegate in Philadelphia

First Continental Congress

In 1773, colonists protested the British tea tax with the Boston Tea Party. Some patriots, including Harrison, thought the Bostonians should pay for the destroyed tea. The British Parliament responded with harsh new laws called the Intolerable Acts. Even with his concerns, Harrison joined 89 members of the Virginia government who spoke out against Parliament's actions. They also asked other colonies to meet for a Continental Congress.

On August 5, 1774, Harrison was chosen as one of seven delegates to represent Virginia at the Congress in Philadelphia. He arrived in Philadelphia on September 2, 1774, for the First Continental Congress. He tended to agree with the older, more traditional delegates. He was less close to the more radical delegates from New England, like John and Samuel Adams. John Adams once described Harrison as someone who loved bold stories, good food, and wine. Harrison himself said he was so eager to join the Congress that "he would have come on foot."

In October 1774, Harrison signed the Continental Association. This agreement with other delegates called for a boycott of British goods. The First Congress ended that month with a Petition to the King. All delegates signed it, asking the king to address their complaints and restore peace.

In March 1775, Harrison attended a meeting in Richmond, Virginia. This meeting is famous for Patrick Henry's "Give me liberty, or give me death!" speech. A plan to raise a military force was approved. Harrison was likely among those who voted against it, but he was still chosen for a committee to carry out the plan. He was also re-elected as a delegate to the next Continental Congress.

Second Continental Congress and Declaration of Independence

When the Second Continental Congress met in May 1775, Harrison lived in Philadelphia with his brother-in-law Peyton Randolph and George Washington. When Randolph died and Washington became commander of the army, Harrison lived alone. He worked hard to get money and supplies for Washington's army.

In 1775, Congress tried to make peace with the King of Britain through the Olive Branch Petition. Harrison strongly supported this petition. However, the king refused to read it and declared the colonists were traitors.

In November 1775, Harrison was part of a committee to check on the army's needs. He traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts with Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Lynch. They looked at the army's needs and morale. After 10 days, they decided that soldiers' pay should be better and the army should have more than 20,000 men. Harrison then returned to Philadelphia to work on defending Virginia and other southern states.

Harrison stayed in Congress until July 1776. He often led the "Committee of the Whole," which meant he guided important discussions. He led the final debates on the Lee Resolution, which was Virginia's first step towards freedom from the King. He also oversaw the final changes and approval of the Declaration of Independence.

The Committee of Five presented Thomas Jefferson's draft of the Declaration on June 28, 1776. The Congress debated it on July 1, 2, and 3. On July 4, it was approved. Harrison reported this to Congress and read the Declaration one last time. Congress then agreed to have it written neatly and signed by everyone present.

Harrison was known for his bold sense of humor. Even his critics said his jokes helped lighten serious meetings. A delegate named Benjamin Rush remembered the signing of the Declaration on August 2, 1776. He said it was a quiet, serious moment. But Harrison broke the silence. He was a large man, and he joked to the smaller delegate Elbridge Gerry: "I shall have a great advantage over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead."

Revolutionary War Efforts

From December 1775 to March 1777, British forces threatened Congress twice. This forced Congress to move, first to Baltimore and then to York, Pennsylvania. Harrison did not like these moves, possibly due to an illness. In 1777, Harrison joined the new Committee of Secret Correspondence. This committee's main goal was to safely communicate with American agents in Britain. Harrison also became the head of the Board of War. This board's first job was to check on the army's movements and prisoner exchanges.

At this time, Harrison disagreed with Washington about Marquis de Lafayette's military rank. Harrison said it was only an honorary title and should not be paid. He also caused debate by supporting the right of Quakers not to fight in the war because of their religion. He argued that Virginia should have more representation than other states in the Articles of Confederation because of its larger population and land. But he was not successful. His time in Congress ended in October 1777. When he left, his farms had been damaged, and his money was reduced.

Harrison returned to Virginia and quickly rejoined the state government. In May 1776, the House of Burgesses was replaced by the Virginia House of Delegates. He was elected Speaker in 1777, beating Thomas Jefferson. He served as Speaker many times. In the following years, he worked on issues like Virginia's western lands, the condition of the army, and the state's defense.

In January 1781, a British force led by Benedict Arnold was near the James River. Harrison was asked to return to Philadelphia to get military help for Virginia. He knew his home, Berkeley, was a target, so he moved his family to safety. In Philadelphia, he asked for more gunpowder, supplies, and troops for Virginia. Arnold moved up the James River, causing much damage. The Harrison family avoided capture, but Arnold burned all the family portraits at Berkeley. Most of Harrison's other belongings and a large part of his house were destroyed. Harrison began to rebuild his home. He also continued to work with Washington to get weapons, troops, and clothing for other southern states.

Governor of Virginia

The new nation won the Revolutionary War in October 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. This gave Harrison only a short break. A month later, he became the fifth Governor of Virginia. He was also the fourth governor to take office that year because of wartime events.

Money was his biggest problem. The war had emptied Virginia's treasury. The government owed money to people both in the state and in other countries. Because of this, Virginia could not take military action far from its borders. So, Harrison opposed attacking Native American tribes in Kentucky and Illinois. Instead, he tried to make peace with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Creek tribes. This led to peace for the rest of his term. This situation caused some arguments with General George Rogers Clark, who wanted to fight aggressively in the west.

As Harrison's term ended, Washington visited the Harrisons in Richmond. Washington praised Harrison's service as governor, even though he could not solve the state's money problems.

Return to Legislature and Death

In 1786, Harrison and other lawmakers disagreed about whether the state should help fund religion. He and his brother Carter Henry Harrison supported a plan to provide money for Christian teachers. This plan failed. Instead, the assembly passed Thomas Jefferson's famous Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. This law created a separation between church and state.

In 1788, Harrison was a member of the Virginia Ratifying Convention. This group decided if Virginia would approve the United States Constitution. Harrison, along with Patrick Henry and George Mason, was unsure about a strong central government. He opposed the Constitution because it did not have a bill of rights. He was in the minority when the Constitution was approved by a small number of votes. He urged those who opposed the Constitution to seek changes through amendments. Washington praised Harrison for trying to prevent extreme actions.

Even with his ongoing gout (a painful joint condition) and money problems, Harrison continued to work in the House of Delegates. He died on April 24, 1791, at his home after being re-elected. The cause of his death is unknown, but he was known to be a heavy man. He was buried at his home with his wife, Elizabeth Bassett. His son William Henry, who was 18, had just started medical school. But he lacked enough money, so he soon left medicine for military service and his own path as a leader.

Legacy

A residence hall at the College of William & Mary is named for Harrison. A main bridge over the James River near Hopewell, Virginia, is also named after him.

Harrison is honored in the Washington, D.C. Memorial to the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |