George Rogers Clark facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Rogers Clark

|

|

|---|---|

1825 portrait by James Barton Longacre

|

|

| Nickname(s) | Conqueror of the Old Northwest Hannibal of the West Washington of the West Father of Louisville Founder of the Commonwealth |

| Born | November 19, 1752 Albemarle County, Virginia |

| Died | February 13, 1818 (aged 65) Louisville, Kentucky |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

Virginia Militia |

| Years of service | 1774–1790 |

| Rank | Brigadier-General |

| Unit | Illinois Regiment |

| Commands held | Western Frontier |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations |

|

| Signature | |

George Rogers Clark (born November 19, 1752 – died February 13, 1818) was an important American soldier and mapmaker from Virginia. He became the highest-ranking American military leader in the western lands during the American Revolutionary War. Clark led the Virginia militia in Kentucky (which was then part of Virginia) for much of the war.

He is most famous for capturing Kaskaskia in 1778 and Vincennes in 1779. These victories happened during his Illinois campaign. They greatly reduced British power in the Northwest Territory. Because of this, Clark was called the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest." The British later gave the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

Clark achieved his biggest military successes before he turned thirty. After the Revolutionary War, he led militia forces in the early battles of the Northwest Indian War. However, he later faced difficulties and had to leave the military. Clark moved to the Indiana Territory but was never fully paid back by the Virginia government for his war expenses. In his later years, he struggled with money and became less well-known. He also tried twice to open the Spanish-controlled Mississippi River for American trade, but these attempts failed. After a stroke, he lost his right leg. Clark was helped in his final years by family, including his younger brother William, who later became famous for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. George Rogers Clark died from a stroke on February 13, 1818.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

George Rogers Clark was born on November 19, 1752, in Albemarle County, Virginia, near Charlottesville. This was also the hometown of Thomas Jefferson. He was the second of ten children born to John and Ann Rogers Clark. His family was of English and possibly Scottish background.

Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son, William, was too young to fight in the war. He later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The family moved from the frontier to Caroline County, Virginia in 1756. This move happened after the French and Indian War began. They lived on a large farm that grew to more than 2,000 acres.

Clark did not have much formal schooling. He lived with his grandfather to attend Donald Robertson's school. Other students there included James Madison. He also had teachers at home, which was common for children of Virginia farmers at that time. There were no public schools. His grandfather taught him how to be a mapmaker.

In 1771, at age 19, Clark went on his first mapmaking trip into western Virginia. In 1772, he first traveled into Kentucky by way of the Ohio River at Pittsburgh. For the next two years, he mapped the Kanawha River area. He also learned about the local plants, animals, and the customs of the different Native American tribes living there. Many settlers were moving into the area because of the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix.

Clark's military career started in 1774. He served as a captain in the Virginia militia. He was getting ready to lead an expedition of 90 men down the Ohio River. But then, fighting broke out between the Shawnee tribe and settlers. This conflict led to Lord Dunmore's War. Most of Kentucky was used by tribes like the Shawnee, Cherokee, and Seneca for hunting. Tribes in the Ohio country were upset because the Kentucky hunting grounds were given away without their agreement. They tried to stop American settlers from moving in, but they were not successful. Clark spent a few months mapping in Kentucky. He also helped organize Kentucky as a county for Virginia before the American Revolutionary War began.

Revolutionary War Service

As the American Revolutionary War started in the East, settlers in Kentucky faced a disagreement about who owned their land. Richard Henderson, a judge from North Carolina, had bought much of Kentucky from the Cherokee. This treaty was not legal. Henderson wanted to create a new colony called Transylvania. However, many Kentucky settlers did not accept Transylvania's power over them.

In June 1776, these settlers chose Clark and John Gabriel Jones to ask the Virginia General Assembly to make Kentucky part of Virginia. Clark and Jones traveled the Wilderness Road to Williamsburg. They convinced Governor Patrick Henry to create Kentucky County, Virginia. Clark was given 500 pounds of gunpowder to help protect the settlements. He was also made a major in the Kentucky County militia. Even though he was only 24, older settlers like Daniel Boone saw him as a leader.

The Illinois Campaign

In 1777, the Revolutionary War became more intense in Kentucky. Lieutenant-governor Henry Hamilton, based at Fort Detroit, gave weapons to his Native American allies. He supported their raids on settlers, hoping they could get their lands back. The Continental Army could not send soldiers to the northwest or to defend Kentucky. So, Kentucky was left to its local people. Clark spent months defending settlements against Native American raiders. During this time, he planned a long-distance attack against the British. His idea was to capture British outposts north of the Ohio River. This would weaken British influence among their Native American allies.

In December 1777, Clark showed his plan to Virginia's Governor Patrick Henry. He asked for permission to lead a secret trip to capture British-held villages. These villages were Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in the Illinois country. Governor Henry made him a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia. He also allowed him to gather troops for the trip. Clark and his officers recruited volunteers from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina.

Clark arrived at Redstone, a settlement south of Fort Pitt, on February 1. He spent several months preparing for the trip. The men gathered at Redstone and left on May 12. They traveled by boat down the Monongahela to Fort Pitt for supplies. Then they went down the Ohio River to Fort Henry and Fort Randolph. They reached the Falls of the Ohio in early June. They spent about a month there getting ready for their secret mission.

In July 1778, Clark led the Illinois Regiment of the Virginia militia. His force of about 175 men crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac. They marched to Kaskaskia, capturing it on the night of July 4 without firing their weapons. The next day, Captain Joseph Bowman and his company captured Cahokia in a similar way. The British soldiers at Vincennes along the Wabash River surrendered to Clark in August. Several other villages and British forts were captured after the British did not get the local support they hoped for. To fight back, Hamilton recaptured the fort at Vincennes, which the British called Fort Sackville, in December 1778.

Clark used his own money and borrowed from friends to continue his campaign. The Virginia government's first payment had run out. He got some of his soldiers to re-enlist and recruited more men. Hamilton waited for spring to start a campaign to retake the forts at Kaskaskia and Cahokia. But Clark planned another surprise attack on Fort Sackville at Vincennes. He left Kaskaskia on February 6, 1779, with about 170 men. They began a very difficult journey over land, facing melting snow, ice, and cold rain. They arrived at Vincennes on February 23 and attacked Fort Sackville. After a siege, Hamilton surrendered the fort on February 25 and was captured. This winter expedition was Clark's most important military success. It made him known as an early American military hero.

News of Clark's victory reached General George Washington. His success was celebrated and helped encourage the alliance with France. General Washington knew that Clark's achievement happened without help from the regular army. Virginia also used Clark's success to claim the Old Northwest. They called it Illinois County, Virginia.

End of the War and Impact

Clark's main goal during the Revolutionary War was to capture the British fort at Detroit. However, he could never gather enough men or weapons to try. Kentucky soldiers usually preferred to defend their own area and stay closer to home. Clark returned to the Falls of the Ohio and Louisville, Kentucky. He continued to defend the Ohio River valley until the war ended.

In June 1780, a combined British and Native American force invaded Kentucky. They captured two settlements and many prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a force that defeated the Shawnee at the village of Peckuwe. This battle is remembered at George Rogers Clark Park near Springfield, Ohio.

In 1781, Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson promoted Clark to brigadier general. He gave him command of all the militia in Kentucky and Illinois. Clark prepared another trip against the British and their allies in Detroit. General Washington sent a small group of regular soldiers to help. But this group was defeated in August 1781 before they could meet Clark. This ended the western campaign.

In August 1782, another British and Native American force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. Clark was the highest-ranking military officer, but he was not at the battle. He was strongly criticized for the disaster. In response, in November 1782, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country. He destroyed several Native American villages along the Great Miami River, including the Shawnee village of Piqua. This was the last major expedition of the war.

Historians have discussed how important Clark's actions were during the Revolutionary War. In 1779, George Mason called Clark the "Conqueror of the Northwest." Because the British gave the entire Old Northwest Territory to the United States in the Treaty of Paris, some historians believe Clark nearly doubled the size of the original thirteen colonies.

More recent historians, like Lowell Harrison, say the campaign was less important in the peace talks. They argue that Clark's "conquest" was more like a temporary stay in the area. While the Illinois campaign is often described as a harsh winter challenge, James Fischer points out that capturing Kaskaskia and Vincennes might not have been as hard as once thought. Kaskaskia was an easy target. Clark had sent spies there who reported "an absence of soldiers in the town."

Clark's men also easily captured Vincennes and Fort Sackville. Before they arrived in 1778, Clark had sent Captain Leonard Helm to Vincennes to gather information. Also, Father Pierre Gibault, a local priest, helped convince the town's people to support the Americans. Before Clark and his men set out to recapture Vincennes in 1779, Francis Vigo gave Clark more information about the town and the fort. Clark already knew about the fort's military strength, its poor location (surrounded by houses that could hide attackers), and its bad condition. Clark's plan of a surprise attack and good information were key to catching Hamilton and his men off guard. After killing five captured Native Americans where the fort could see, Clark forced its surrender.

Later Years and Challenges

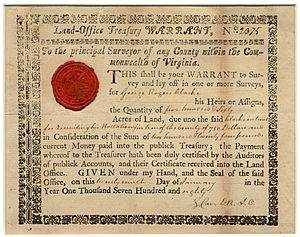

After Clark's victories, settlers continued to move into Kentucky and develop land north of the Ohio River. On December 17, 1783, Clark was made the main surveyor of lands given to soldiers for their service. From 1784 to 1788, Clark worked as the superintendent-surveyor for Virginia's war veterans. This job gave Clark a small income, but he spent little time on it.

In 1785, Clark helped negotiate the Treaty of Fort McIntosh and the Treaty of Fort Finney in 1786. However, fighting between Native Americans and European-American settlers continued to grow. In 1786, Clark led an expedition of 1,200 men against Native American villages along the Wabash River. This campaign, one of the first actions of the Northwest Indian War, did not end in a clear victory. About three hundred soldiers refused to continue due to a lack of supplies, so Clark had to retreat. He did manage to arrange a ceasefire with the native tribes. Clark then left Kentucky and moved across the Ohio River to the Indiana frontier, near what is now Clarksville, Indiana.

Life in Indiana and Financial Struggles

After his military service, especially after 1787, Clark spent much of his life dealing with money problems. Clark had paid for most of his military campaigns with borrowed money. When people he owed money to started asking for it back, Clark could not get paid back by Virginia or the United States Congress. Because records were not kept well on the frontier during the war, Virginia refused to pay him. They claimed Clark's receipts for his purchases were not valid.

As a reward for his war service, Virginia gave Clark a gift of 150,000 acres of land. This land became known as Clark's Grant in southern Indiana. Soldiers who fought with Clark also received smaller pieces of land. Clark's Grant and his other land meant he owned land that included parts of present-day Clark County, Indiana, and nearby Floyd and Scott Counties. Even though Clark owned thousands of acres, he was "land-poor." This means he owned a lot of land but did not have money to develop it. George Rogers Clark's receipts were later found in Virginia's records. They showed his record keeping was complete and correct. He was not paid back due to the state's problems, so Clark was proven right, but not officially. He started writing his life story around 1791, but it was not published while he was alive.

Later Attempts and Health Decline

On February 2, 1793, with his military career seemingly over and his future looking uncertain, Clark offered his help to Edmond-Charles Genêt. Genêt was a controversial ambassador from revolutionary France. Clark hoped to earn money to keep his property. Many Americans were angry that the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana, would not let Americans use the Mississippi River freely. This river was their only easy way to transport goods long distances.

Genêt made Clark a "Major General in the Armies of France." Clark began to plan a campaign to capture Spanish-controlled towns like New Madrid, St. Louis, Natchez, and New Orleans. He got help from old friends and the quiet support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby. Clark spent $4,680 of his own money on supplies.

However, in early 1794, President Washington issued a statement forbidding Americans from violating U.S. neutrality. He threatened to send General Anthony Wayne to stop the expedition. The French government called Genêt back and canceled the military roles he gave to Americans. Clark's planned campaign slowly fell apart. He could not convince the French to pay him back for his expenses. Clark's reputation, already damaged, was further hurt by his involvement in these foreign plans.

In his later years, Clark's growing debts made it impossible for him to keep his land. He gave much of his land to friends or transferred ownership to family members. This way, his creditors could not take it. Lenders eventually took almost all the property that was still in his name. Clark, who once owned the most land in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small piece of land in Clarksville. In 1803, Clark built a cabin overlooking the Falls of the Ohio. He lived there until his health failed in 1809. He also bought a small gristmill, which he ran with two enslaved people he owned.

Clark knew a lot about the region. He became an expert on the West's natural history. Over the years, he welcomed travelers to his home. Clark shared details about the area's plants and animals with John Pope and John James Audubon. He also hosted his brother, William, and Meriweather Lewis, before their expedition to the Pacific Northwest. Clark also gave information about the Ohio Valley's native tribes to Allan Bowie Magruder.

When the Indiana Territory started the Indiana Canal Company in 1805 to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio, Clark was named to the board of directors. He helped survey the route for the canal. The company failed the next year before construction could begin. Two of the board members, including Vice President Aaron Burr, were arrested. A large part of the company's investments, $1.2 million, was never found.

Return to Kentucky and Final Years

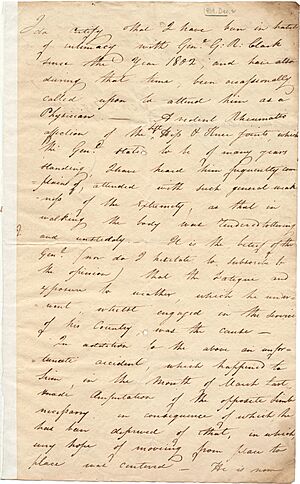

Poor health affected Clark in his last years. In 1809, he had a severe stroke. He fell into a burning fireplace and burned his right leg so badly that it had to be removed. This injury made it impossible for Clark to run his mill or live on his own. So, he moved to Locust Grove. This was a farm eight miles from Louisville. He lived with his sister, Lucy, and her husband, Major William Croghan.

In 1812, the Virginia General Assembly gave Clark a pension of four hundred dollars per year. They also finally recognized his service in the Revolutionary War by giving him a ceremonial sword.

Death and Lasting Impact

After another stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove on February 13, 1818. He was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later. Clark's remains, along with those of his family members, were later moved on October 29, 1869. They were reburied at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.

At his funeral, Judge John Rowan summed up Clark's importance: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around." Clark's life was closely connected to events in the Ohio-Mississippi Valley. This was a key time when many Native American tribes lived there. The British, Spanish, French, and the new U.S. government all claimed the land. As a member of the Virginia militia, Clark's campaign into the Illinois country helped Virginia claim lands in the region. His military service also made him an "important source of leadership and information" about the West.

Clark is best known as a war hero of the Revolutionary War in the West. This is especially true for his leadership in the secret expeditions that captured Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes in 1778–79. Some historians believe his campaign helped American claims to the Northwest Territory during the negotiations for the Treaty of Paris (1783). Clark's Grant, the large area of land he received for his military service, included much of Clark County, Indiana. It also included parts of Floyd and Scott Counties. This land also contains the present-day site of Clarksville, Indiana, the first American town laid out in the Northwest Territory (in 1784). Clark was the first chairman of the Clarksville, Indiana, board of trustees. However, Clark could not keep ownership of his land. At the end of his life, he was poor and in poor health.

Several years after Clark's death, the government of Virginia gave his estate $30,000. This was a partial payment for the debts it owed him. The Virginia government continued to repay Clark for decades. The last payment to his estate was made in 1913. Clark never married and did not keep records of any romantic relationships. However, his family believed he was once in love with Teresa de Leyba, the sister of Fernando de Leyba, the Spanish lieutenant governor of Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin suggest his lifelong sadness over this failed romance.

Honors and Tributes

- On May 23, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge ordered a memorial to Clark to be built at Vincennes, Indiana. The George Rogers Clark Memorial was finished in 1933 and dedicated on June 14, 1936, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This Roman-style temple was built where Fort Sackville was believed to have stood. The site, now called the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, became part of the National Park Service in 1966. Hermon Atkins MacNeil created the monument's 7.5-foot bronze statue of Clark. The monument's walls have seven murals showing Clark's famous expedition.

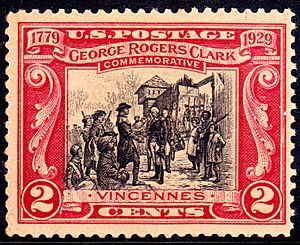

- On February 25, 1929, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Fort Sackville's surrender, the U.S. Postal Service issued a two-cent postage stamp showing the event.

- In 1975, the Indiana General Assembly named February 25 as George Rogers Clark Day in Indiana.

- In 1979, Indiana's car license plates celebrated the 200th anniversary of Clark's capture of Fort Sackville.

- A bronze statue of Clark is one of several on Monument Circle in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana. Sculptor John H. Mahoney created the statue, which was finished in 1895.

- The Daughters of the American Revolution placed a statue by sculptor Leon Hermant at Metropolis, Illinois, in the early 1900s. This is the site of Fort Massac.

- Sculptor Felix de Weldon created the Clark statue at Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere in Louisville, Kentucky.

- Charles Keck created the memorial statue of Clark at the site of the Battle of Piqua, near Springfield, Ohio.

- Robert Aitken's bronze sculpture of Clark was put up on Monument Square at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1921. It was removed by the University of Virginia in July 2021.

- A Clark statue was put up in Riverview Park, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River at Quincy, Illinois, in 1909.

- In April 1929, the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution of Muncie, Indiana, put up a monument to Clark on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Clark spent his childhood about 40 miles from Fredericksburg.

- Clark is the namesake of several counties in the United States: Clark County, Illinois; Clark County, Indiana; Clark County, Kentucky; Clark County, Ohio; Clarke County, Virginia; and Clark County, Wisconsin.

- Several communities in the U.S. have been named in his honor: Clarksville, Indiana; Clarksville, Tennessee; and Clarksburg, West Virginia.

- Schools named in Clark's honor include:

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School of Chicago, Illinois.

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Clarksville, Indiana (closed 2010)

- George Rogers Clark College, Indianapolis, Indiana (closed 1992)

- George Rogers Clark Middle School, Vincennes, Indiana

- George Rogers Clark Junior High School, Springfield, Ohio (now closed)

- George Rogers Clark Middle/High School, Whiting, Lake County, Indiana (school closing following the 2020–21 school year)

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Paducah, Kentucky

- George Rogers Clark High School, Winchester, Clark County, Kentucky

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School, Charlottesville, Virginia

- Other sites and structures:

- The George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge (Second Street Bridge), built in 1929, carries U.S. Highway 31 over the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky.

- In 1979, the Indiana American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and the Indiana Highway Commission put up about 600 signs. These signs created the George Rogers Clark Trail, marking the routes Clark and his men used in Indiana during the Revolutionary War.

- Clark Street in Chicago, is named in his honor.

- The Liberty Ship SS George Rogers Clark. Launched November 9, 1942; Commissioned January 2, 1943; Sold privately 1947, scrapped 1963.

See also

In Spanish: George Rogers Clark para niños

In Spanish: George Rogers Clark para niños

- History of Louisville, Kentucky

- List of people from the Louisville metropolitan area

- George Rogers Clark Flag

- Old Clarksville Site

- George Rogers Clark (1985 bust)

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |