Lord Dunmore's War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lord Dunmore's War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, for whom the war is named. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Shawnees Mingos |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hokolesqua, Talgayeeta |

Lord Dunmore, Andrew Lewis, Angus McDonald, William Crawford |

||||||

Lord Dunmore's War, also known as Dunmore's War, was a short but important conflict in 1774. It was fought between the Colony of Virginia and two Native American nations: the Shawnee and the Mingo.

The war was named after John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, who was the Governor of Virginia at the time. He asked Virginia's government, called the House of Burgesses, to declare war. He also called up the militia, which was a group of citizen soldiers.

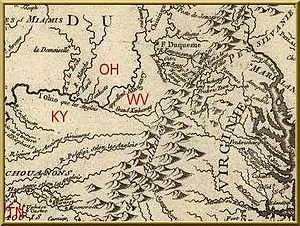

This war happened because of growing tension. White settlers were moving into lands south of the Ohio River. These lands are now parts of West Virginia, southwestern Pennsylvania, and Kentucky. Native Americans had rights to hunt there. Settlers often attacked Native American lands, which led to Native American groups fighting back. The war was declared to bring peace to the area.

The war ended quickly after Virginia won the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10, 1774. Because of this victory, the colonists gained more control over the land. The Ohio River was recognized as the boundary between Native American lands (to the west) and the Thirteen Colonies (to the east).

Even though the Native American leaders signed the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, not everyone agreed with it. Some tribes felt they had given up too much land. Others believed that another war would only lead to more losses. When the American Revolutionary War started in 1776, many Native American groups joined the British. They attacked the settlers during the Revolution.

Contents

Why the War Started

The land south of the Ohio River was a hunting ground for many Native American tribes. The powerful Iroquois Confederacy also claimed this area. After the Seven Years' War (also known as the French and Indian War), France gave up its claims to this land to Britain in 1763.

In 1768, British officials made a deal with the Iroquois. This was called the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. Through this treaty, the British gained control of the land south of the Ohio River. However, many other Ohio Native American tribes who hunted there did not agree with this treaty. They prepared to defend their hunting rights.

The Shawnee were leaders in this resistance. They were very strong and organized a group of other tribes to oppose the British and the Iroquois. British officials tried to keep other tribes from joining the Shawnee. So, when the fighting began, the Shawnee faced the Virginia militia with few allies.

After the 1768 treaty, many explorers, surveyors, and settlers moved into the region. This led to direct conflicts with Native Americans. George Washington wrote in 1770 that Native Americans, even women, were skilled at using canoes for hunting and trading furs.

In September 1773, a famous hunter named Daniel Boone led about 50 settlers. They tried to start a settlement in Kentucky County, Virginia. On October 9, 1773, Boone's 16-year-old son, James, and a small group were attacked. The attackers were from the Delaware, Shawnee, and Cherokee tribes. They wanted to show their opposition to the new settlements. James Boone and another teenager were captured and killed. These brutal killings shocked the settlers. Boone's group stopped their journey. This event was one of the first steps toward Lord Dunmore's War. For the next few years, Native American groups who opposed the treaty kept attacking settlers.

Rising Tensions: "Cresap's War"

One of the settlers was Captain Michael Cresap. He owned a trading post and had claimed large areas of land in what is now West Virginia. In early 1774, he went there with his men to settle his land.

Another group, including George Rogers Clark, who later became a general, gathered at the mouth of the Little Kanawha River. They heard reports that Native American groups were robbing and killing traders and surveyors on the Ohio River. They believed that the Shawnee and their allies were ready for war. This group decided to attack a Native American village.

They asked Captain Cresap, who had combat experience, to lead them. Cresap convinced them not to attack right away. He thought that attacking would definitely start a war, and the settlers would be blamed. He suggested they wait a few weeks at a settlement called "Zanesburg" (now Wheeling).

When they arrived in Zanesburg, the area was in a panic. People were scared by stories of Native American attacks. Colonists living on the frontier rushed to the town for safety. Cresap's group grew with many volunteers ready to fight.

News reached Fort Pitt, and the commander, Captain John Connolly, asked the volunteers to wait. He was trying to find out what the local tribes intended. Cresap then received a second message from Connolly. It said that the Shawnee tribes had signaled they intended war.

On April 26, Cresap held a meeting. After reading Connolly's letter, the group declared war against the Native Americans. The next day, settlers chased some Native American canoes downriver and fought them. Clark's group then moved to Cresap's headquarters for safety.

The Yellow Creek Massacre

Right after the Pipe Creek attack, settlers killed family members of the Mingo leader Logan. Before this, Logan had wanted peace with the settlers. His hunting party was camped on the Ohio River. On April 30, some of his group, including his younger brother and two women, crossed the river to a settler's cabin. About 30 frontiersmen, led by Daniel Greathouse, suddenly attacked them. They killed everyone except an infant.

When Logan heard about the massacre, he was told that Cresap was responsible. However, many people knew that Greathouse and his men were the real attackers. Settlers on the frontier realized these killings would likely cause other Native American nations to attack. People living on the frontier quickly sought safety in forts or fled eastward. Their fears were justified. Logan and small groups of Shawnee and Mingo soon began attacking frontier settlers to get revenge for the murders at Yellow Creek.

Dunmore's Expedition

Gathering Forces

In early May 1774, Governor Dunmore learned that fighting had started on the Ohio River. He asked the government to allow him to raise a militia and send a volunteer army into the Ohio River valley.

Dunmore split his forces into two groups. He led about 1,700 men down the Ohio River from Fort Pitt. Another group of 1,100 troops, led by Colonel Andrew Lewis, traveled from Camp Union (now Lewisburg, West Virginia). The plan was for both groups to meet at the mouth of the Great Kanawha River.

Dunmore traveled to Fort Pitt and then moved his forces down the Ohio. On September 30, he arrived at Fort Fincastle (later Fort Henry), which he had ordered to be built.

Lewis's force marched to the Kanawha River and then downriver. They reached the river's mouth on October 6 and set up "Camp Pleasant" (now Point Pleasant). Dunmore was not there yet, so Lewis sent messengers to find him. On October 9, Dunmore sent a message back. He said he would go to the Shawnee towns and ordered Lewis to cross the Ohio River and meet him there.

Battle of Point Pleasant

On October 10, before Lewis could cross the Ohio, his army was surprised by warriors led by Chief Cornstalk. The Battle of Point Pleasant lasted almost all day. It was a fierce fight, with hand-to-hand combat. Lewis's army had about 215 casualties, meaning 75 were killed (including Lewis's brother) and 140 were wounded. His forces defeated the Native American warriors, who retreated across the Ohio River. They had lost about 40 warriors. Captain George Mathews of the Virginia militia was praised for a clever move that helped Cornstalk's forces retreat.

Peace Talks and Treaty

After the battle, Dunmore and Lewis moved their armies into Ohio. They got within eight miles of the Shawnee towns. Here, they built a temporary camp called Camp Charlotte. They met with Chief Cornstalk to start peace talks.

The Treaty of Camp Charlotte was signed on October 19, 1774. In this treaty, the Shawnee agreed to stop hunting south of the Ohio River. They also agreed to stop bothering travelers on the river. Chief Logan, though he said he would stop fighting, refused to attend the formal peace talks. It was here that a famous speech by Logan, known as Logan's Lament, was shared.

The Mingo tribe refused to accept the treaty terms. So, Major William Crawford attacked their village, destroying it. These actions, along with the Shawnee's agreement at Camp Charlotte, mostly ended the war.

The treaty was confirmed again the next year at Fort Pitt. At that meeting, leaders from the Continental Congress asked representatives from several tribes to stay neutral in the growing conflict with Great Britain.

Fort Gower Resolves

In November 1774, the Virginia army returned to a camp they had set up earlier, called Fort Gower. There, they learned that the Continental Congress in Philadelphia had decided to boycott English goods. This was a response to the Coercive Acts, which were harsh laws from Britain.

Recognizing that this boycott was an act of rebellion, the Virginia soldiers wrote a statement. It was called the "Fort Gower Resolves." In this statement, they showed their growing desire for independence from Britain. Many future heroes of the American Revolution were among these soldiers.

The Resolves stated that they would be loyal to King George III as long as he ruled fairly. But they also declared that their love for liberty and America's rights was more important. They promised to use their strength to defend American liberty and rights. They said they would do this not in a wild way, but when their country called them to act. They also showed great respect for Governor Dunmore.

These Resolves were published in the Virginia Gazette on December 22, 1774. This was one of the first times colonists clearly stated they were ready to use force against the British Crown to protect their rights. It was like an early declaration of independence, happening even before the famous events in Concord and Philadelphia.

Aftermath

After the treaty, Dunmore's militia returned home. They traveled over the Allegheny Mountains back to Williamsburg, which was Virginia's capital at the time. However, the peace did not last long.

On March 24, 1775, a group of Shawnee attacked Daniel Boone in Kentucky. And in May 1776, as the American Revolution began, the Shawnee joined other Native American leaders. They again declared war on the Virginia colonists. These conflicts became part of the Cherokee–American wars that lasted from 1776 to 1794.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de Lord Dunmore para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de Lord Dunmore para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |