Patrick Henry facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Patrick Henry

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 1st and 6th Governor of Virginia | |

| In office December 1, 1784 – December 1, 1786 |

|

| Preceded by | Benjamin Harrison V |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Randolph |

| In office July 5, 1776 – June 1, 1779 |

|

| Preceded by | Edmund Pendleton (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 29, 1736 Studley, Virginia, British America |

| Died | June 6, 1799 (aged 63) Brookneal, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Anti-Federalist Anti-Administration Federalist |

| Spouses |

Sarah Shelton

(m. 1754; died 1775)Dorothea Dandridge

(m. 1777; |

| Profession | Planter, lawyer |

| Signature |  |

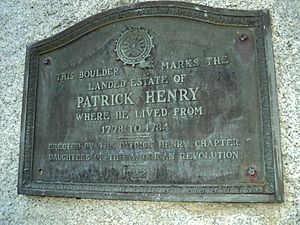

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736 – June 6, 1799) was an important American leader during the time of the American Revolution. He was a lawyer, a farmer, and a politician. He is most famous for his powerful speech in 1775 where he declared, "Give me liberty, or give me death!" Patrick Henry was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He served as the first and sixth governor of Virginia after the colonies became independent. He was governor from 1776 to 1779 and again from 1784 to 1786.

Henry grew up in Hanover County, Virginia. He mostly learned at home. After trying to run a store and helping at his father-in-law's tavern, he taught himself law. He started his law practice in 1760. He quickly became well-known for winning a case called the Parson's Cause. Later, he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. There, he became famous for speaking out against the Stamp Act of 1765.

In 1774 and 1775, Henry was a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses. He became very popular in Virginia because of his speeches and by leading troops toward the colonial capital, Williamsburg. Henry strongly pushed for independence from Britain. When the Fifth Virginia Convention agreed in 1776, he helped write the Virginia Declaration of Rights and Virginia's first constitution. He was then elected as Virginia's first governor. He served five one-year terms in total.

After being governor, Henry served in the Virginia House of Delegates. He became governor again in 1784. He worried about a strong national government under the Articles of Confederation. Because of this, he refused to be a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. He also strongly opposed the new Constitution because it did not yet include a Bill of Rights. In his later years, he returned to practicing law. He turned down several jobs in the new federal government. Patrick Henry owned slaves throughout his life. He hoped to see slavery end, but he did not have a plan for how to do it beyond stopping the import of new slaves. He is remembered for his powerful speeches and for being a strong supporter of American independence.

Contents

Early Life and Family (1736–1759)

Patrick Henry was born on May 29, 1736, at his family's farm called Studley. This farm was in Hanover County, in the Colony of Virginia. His father, John Henry, came from Scotland. His mother, Sarah Winston Syme, was a wealthy widow from a well-known local family.

Henry went to a local school until he was about 10 years old. After that, his father taught him at home. Young Patrick enjoyed music, dancing, and especially hunting. Because of a tradition called primogeniture, his older half-brother would inherit most of the family's land and slaves. This meant Patrick needed to find his own way in the world.

At age 15, he worked as a clerk for a local merchant. A year later, he opened a store with his older brother, William. However, the store was not successful.

Religion was very important in Henry's life. His father and his uncle were both very religious and influenced him greatly. Even so, he did not like that the Anglican Church was the official religion in Virginia. He worked to protect religious freedom throughout his career.

In 1754, Henry married Sarah Shelton. Her father gave the couple six slaves and a 300-acre farm called Pine Slash Farm. This farm was near Mechanicsville. The land at Pine Slash was worn out from earlier farming. Henry worked with the slaves to clear new fields. The late 1750s were dry years in Virginia. After their main house burned down, Henry and his family moved to the Hanover Tavern. Sarah's father owned this tavern.

Henry often helped host guests at Hanover Tavern. He would entertain them by playing the fiddle. One guest was Thomas Jefferson, who was 17 at the time. Jefferson was on his way to study at William & Mary College. Jefferson later wrote that he got to know Henry well during this time.

Becoming a Lawyer and Politician (1760–1775)

The Parson's Cause Case

While at Hanover Tavern, Henry studied law. It is not clear how long he studied, but he later said it was as little as one month. In 1760, he applied for a lawyer's license. He appeared before important lawyers in Williamsburg, the colonial capital. The examiners were impressed by Henry's sharp mind, even though he did not know much about legal procedures. He passed in April 1760 and opened his law practice. He worked in Hanover and nearby counties.

In the 1750s, dry weather caused tobacco prices to rise. Money was scarce in Virginia. Salaries were often paid in tobacco. Before the drought, tobacco was usually two pence per pound. In 1755 and 1758, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed the Two Penny Act. This law allowed debts paid in tobacco to be settled at the rate of two pence per pound for a short time. This included payments to public officials, like ministers. Several ministers asked the Board of Trade in London to overturn this law, which they did.

Five ministers then sued for their back pay. These cases were known as the Parson's Cause. Only one minister, Reverend James Maury, won his case. A jury was to decide the amount of money he would get in Hanover County on December 1, 1763. Henry was hired by Maury's parish to represent them at this hearing.

After the evidence was shown, Maury's lawyer praised the clergy. Many ministers were there to listen. Henry then gave a one-hour speech. He did not talk about the amount of money. Instead, he focused on how the king's government had no right to overturn the Two Penny Act. Henry said that any king who canceled good laws, like the Two Penny Act, was a "tyrant." He said such a king "forfeits all right to his subjects' obedience." He also said the clergy, by challenging a fair law meant to help people, had shown themselves to be "enemies of the community." Henry asked the jury to make an example of Maury. He suggested the jury award only one farthing in damages. The jury quickly returned with a decision: one penny. Henry was seen as a hero. His popularity grew greatly, and he gained many new clients after this case.

Speaking Out Against the Stamp Act

After the Parson's Cause, Henry became popular in Virginia's rural areas. People liked his speeches defending the rights of common people and his friendly way. He further boosted his standing in 1764 by representing Nathaniel West Dandridge. Dandridge was accused of bribing voters, which was common but illegal. Henry gave a strong speech defending voters' rights, though the exact words are lost. He lost the case but met important members of the House of Burgesses.

In 1765, Henry was elected to represent Louisa County in the House of Burgesses. He went to Williamsburg right away, as the session had already started.

Britain had spent a lot of money fighting the Seven Years' War (also called the French and Indian War in North America). This war nearly doubled Britain's debt. Since much of the war was in North America, the British government looked for ways to tax the American colonies directly. The Stamp Act of 1765 was a way to raise money and show Britain's authority over the colonies.

Patrick Henry joined the legislature on May 20. Many members had already left town. Around May 28, a ship arrived with news: the Stamp Act had passed. On May 29, Henry introduced the Virginia Stamp Act Resolves. The first two resolutions said that colonists had the same rights as people in Britain. The next two said that taxes should only be collected by the colonists' own representatives. The fifth resolution was the most daring. It named the Virginia legislature, the General Assembly, as the only body allowed to tax Virginians. Two other resolutions were also offered, but it's not certain who wrote them.

The Burgesses passed the first five resolutions. The other two, which said Parliament had no right to tax Virginians and called anyone who said so an enemy, did not pass. On May 31, with Henry gone, the Burgesses removed the fifth resolution. The Royal Governor, Francis Fauquier, would not let any of them be printed in the official newspaper. However, newspapers in the colonies and Britain printed all seven resolutions. They presented them as if they had all been passed by Virginia. These resolutions, which were more radical as a group than what actually passed, reached Britain by mid-August. They were the first American response to the Stamp Act. In North America, they sparked strong opposition to the Stamp Act. They made Virginia a leader in opposing Britain's actions. Henry quickly became known as a strong opponent of British rule.

Life as a Lawyer and Landowner (1766–1773)

In the late 1760s and early 1770s, Henry focused more on his personal life. Still, he gained influence in the House of Burgesses, serving on important committees. His family moved to a new house on his land in Louisa County around 1765. They lived there until 1769, when they returned to Hanover County. His law practice stayed busy until the royal courts closed in 1774. In 1769, Henry was allowed to practice before the General Court of Virginia in Williamsburg. This was a more respected court than the county courts.

Henry used some of his earnings to buy land on the frontier. This land is now in western Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. He claimed ownership, even though Native Americans controlled much of it. He tried to get the colonial (and later state) government to recognize his claims. Many leading Virginians, like George Washington, did this. Henry saw the potential of the Ohio Valley and was involved in plans to start new settlements. In 1771, money from land deals allowed him to buy Scotchtown. This was a large plantation in Hanover County. It was one of the biggest mansions in Virginia.

Owning plantations like Henry's meant owning slaves. Henry owned slaves from the time he married at age 18. He believed slavery was wrong and hoped it would end. However, he had no clear plan for how to do this. He did not think plans to send freed slaves to Africa were practical. In 1773, he wrote, "I am the master of slaves of my own purchase. I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living here without them. I will not, I cannot justify it." Yet, the number of slaves he owned grew over time. After his second marriage in 1777, he owned even more. When he died in 1799, he owned 67 slaves. Henry and others tried to stop the import of slaves to Virginia, succeeding in 1778. They thought this would help end slavery. However, after independence, more slaves were born than died in Virginia. This made Virginia a source of slaves sold to the South.

Renewed Action and the First Continental Congress (1773–1775)

In 1773, Henry disagreed with the royal governor, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore. The governor had sent British soldiers to Pittsylvania County to catch a group of counterfeiters. Once caught, they were taken straight to Williamsburg for trial. This ignored the usual rule that trials should start in the county where the crime happened. This was a sensitive issue because of the recent Gaspee incident in Rhode Island. In that case, the British tried to take people who burned a British ship overseas for trial.

The House of Burgesses wanted to criticize Dunmore. Henry was part of a committee that wrote a resolution. It thanked the governor for catching the gang. But it also said that using the "usual mode" of criminal procedure protected everyone. They also created a plan for a committee of correspondence. This committee would communicate with leaders in other colonies to share information and work together. Henry was a member of this committee.

By this time, Henry believed that conflict with Britain and independence were unavoidable. In 1774, news arrived that Parliament had voted to close the port of Boston. This was in response to the Boston Tea Party. Several burgesses, including Henry, met at the Raleigh Tavern to plan a response. George Mason, a former burgess, said Henry took the lead. Mason and Henry formed a close political friendship. The resolution Henry's committee produced called for June 1, 1774, the day Boston's port was to close, to be a day of fasting and prayer. The Burgesses passed it, but Governor Dunmore dissolved the body.

The former legislators then met at the Raleigh Tavern. They decided to meet again as a convention in August. They also called for a boycott of tea and other products. The five Virginia Conventions (1774–1776) guided Virginia toward independence. Many county meetings supported their work. They denied Parliament's authority and called for boycotts. The first convention met in Williamsburg on August 1. Dunmore was away fighting Native Americans, so he could not interfere. The convention was divided between those who wanted to separate from Britain and those who hoped for a compromise. They met for a week. A major decision was to elect delegates to a Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Henry was chosen as one of seven delegates. He tied for second place with Washington.

Washington invited Henry to stop at his estate, Mount Vernon, on the way to Philadelphia. Henry and Pendleton, another Virginia delegate, accepted. Delegates and important people in Philadelphia were very interested in the Virginians. Few people in other colonies had met them. This was Henry's first long stay in the North. But he found that his actions were well known. The Congress began on September 5, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall. Silas Deane of Connecticut described Henry as the "compleatest speaker I ever heard." He praised Henry's voice and elegant style. The secretary of the Congress, Charles Thomson, wrote that Henry, dressed simply, soon "electrified the whole house" with his powerful arguments.

Henry was involved in the first disagreement in Congress. He argued that larger colonies should have more votes. He said colonial borders should be ignored for Americans to unite. "The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more. I am not a Virginian, but an American." Henry lost this argument. His dramatic style made Congress leaders worried he would be unpredictable. He was put on a committee to look into trade rules, but it did not achieve much. Henry believed Congress should prepare for war. He agreed with John Adams and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts. But not everyone felt that way. Henry was not a very influential member of the group. Congress decided to send a petition to the king. Henry prepared two drafts, but neither was used. When Congress approved a draft by John Dickinson on October 26, Henry had already left for home. The petition was rejected in London.

After the birth of their sixth child in 1771, Patrick's wife, Sarah Shelton Henry, began to show signs of mental illness. One reason for moving to Scotchtown was to be near family. Henry's biographer, Jon Kukla, thinks she had postpartum psychosis, for which there was no treatment then. Sometimes, she had to be restrained. Even though Virginia opened the first public mental hospital in North America in 1773, Henry decided she was better off at Scotchtown. He prepared a large apartment for her there. She died in 1775. After her death, Henry avoided things that reminded him of her. He sold Scotchtown in 1777.

The "Liberty or Death" Speech (1775)

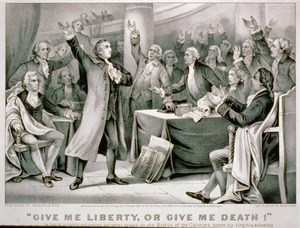

Hanover County chose Henry as a delegate to the Second Virginia Convention. This meeting took place at St. John's Episcopal Church in Richmond on March 20, 1775. Richmond was chosen because it was safer from royal authority. The convention discussed whether Virginia should use language from a petition by planters in Jamaica. This document complained about British actions but said the king could still veto colonial laws. It also urged reconciliation.

Henry proposed changes to create a militia (citizen army) independent of royal authority. He spoke as if conflict with Britain was unavoidable. This angered moderate members. On March 23, he defended his changes. He ended with his most famous words:

If we were base enough to desire it, it is now too late to retire from the contest. There is no retreat but in submission and slavery! Our chains are forged! Their clanking may be heard on the plains of Boston! The war is inevitable and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come.

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!

As he finished, Henry pointed an ivory letter opener toward his chest. He was imitating the Roman patriot Cato the Younger. Henry's speech won the day, and the convention adopted his changes. However, they passed by a very small margin. Many delegates were unsure where Henry's strong resistance would lead. Few counties formed independent militia groups right away.

The words of Henry's speech first appeared in print in Wirt's 1817 biography. This was 18 years after Henry died. Wirt talked to men who had heard the speech and others who knew people who were there. Everyone agreed the speech had a huge impact. But it seems only one person tried to write down the exact words. Judge St. George Tucker, who was there, gave Wirt his memories. Wirt wrote back saying he used Tucker's recollections almost entirely. The original letter from Tucker is now lost.

For 160 years, Wirt's account was believed completely. In the 1970s, historians began to question if Wirt's version was truly accurate. Today, historians note that Henry was known to use fears of Indian and slave revolts to push for military action against the British. Also, the only written first-hand account of the speech says Henry used some harsh language that Wirt did not include in his heroic version. Tucker's account was based on memories, decades after the speech. He wrote, "In vain should I attempt to give any idea of his speech." Scholars still debate how much of the speech we know is from Wirt or Tucker.

The Gunpowder Incident

On April 21, 1775, Governor Dunmore ordered the Royal Marines to take gunpowder from the magazine in Williamsburg. They moved it to a naval ship. The gunpowder belonged to the government for emergencies, like a slave uprising. Dunmore's actions angered many Virginians.

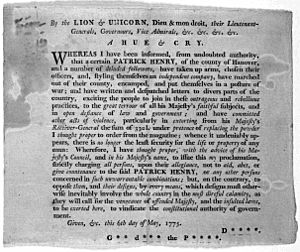

Henry had left for Philadelphia to attend the Second Continental Congress. But a messenger reached him before he left Hanover County. Henry returned to lead the local militia. He wanted the gunpowder returned or for the colonists to be paid for it. On May 2, Henry led his troops toward Williamsburg. Dunmore wrote that it looked like "actual War." By this time, news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord had arrived. Many Virginians believed war with Britain had begun. Henry's troops were joined by eager volunteers. He likely had enough force to take Williamsburg. But important messengers urged caution, slowing his advance. In New Kent County, about 16 miles from Williamsburg, three of Henry's fellow delegates helped convince him to stop his march. Henry insisted the colonists be paid. A member of the Governor's Council agreed to pay the value of the powder.

Governor Dunmore issued a statement against "a certain Patrick Henry, of the County of Hanover, and a Number of his deluded Followers." However, 15 county committees quickly approved Henry's actions. When he finally left for Philadelphia, militia members escorted him to the Potomac. They cheered as his ferry left. Not everyone approved. Some moderates were worried by Henry's march. They feared he might start a conflict where Virginia would face Britain alone. They also saw him as a threat to property rights. But as support for independence grew, opponents either joined the movement or stayed quiet.

Henry arrived late at Congress on May 18, 1775. Jefferson later said Henry played only a small role. Henry supported the appointment of Washington as head of American forces. At the end of the session in August, Henry left Philadelphia for Virginia. He would never again hold office outside Virginia.

While Henry was returning, the Third Virginia Convention met in August. They made him a colonel of the 1st Virginia Regiment. He started this job later that month. Henry had little military experience, but this was not a big problem then. General Washington, however, felt the convention had made a "Capital mistake" by putting Henry in the army. In September, Virginia's Committee of Safety put Henry in charge of all Virginia's forces. Despite the high title, Henry was under strict civilian control. Some moderates agreed to his appointment because they thought it would keep the unpredictable Henry contained.

Henry began to organize his regiment and had no trouble recruiting men. As commander, he also started to organize a navy. In November 1775, Dunmore, who had left Williamsburg but still held Norfolk, made a statement. He offered freedom to any black slave or indentured servant who would join his forces. His forces already included hundreds of former slaves. Henry wrote to all county lieutenants. He said Dunmore's statement was "fatal to the publick Safety." He urged "unremitting Attention to the Government of the SLAVES" to stop this "dangerous Attempt." He said "Constant, and well directed Patrols, seem indispensably necessary."

Henry himself saw no direct fighting. There were whispers in the convention against his command. Some feared he was too radical to be a good military leader. In February 1776, Virginia's forces were reorganized. They were placed under Continental command. Henry was to keep his rank of colonel but would be under a former subordinate. Henry refused and left the army. His troops were very upset by this insult to him. They thought about leaving the service, but Henry calmed them down.

Independence and First Time as Governor

Henry did not attend the Fourth Virginia Convention in December 1775. He was not allowed because of his military job. Once he was a civilian again, the voters of Hanover County elected him to the fifth convention in April 1776. This meeting was in May. Most delegates wanted independence but disagreed on how and when to declare it. Henry introduced a resolution declaring Virginia independent. It also urged Congress to declare all colonies free. The final resolution was largely based on Henry's ideas. It passed unanimously on May 15, 1776. Besides declaring Virginia independent, the resolution told the state's delegates in Congress to push for American independence. They did, with Lee introducing the motion and Jefferson writing the Declaration.

The convention then started to create a constitution for Virginia's government. Henry was on a committee led by Archibald Cary. Virginia's new government became a national concern. Jefferson, in Philadelphia, sent a plan. John Adams sent Henry a pamphlet with his own ideas. Henry replied, "your sentiments are precisely the same I have long since taken up." But George Mason's plan for Virginia's government was mostly used. It gave a lot of power to the Virginia House of Delegates, the lower house of the legislature. The House of Delegates and the Senate of Virginia together formed the General Assembly. Under the 1776 constitution, the governor, chosen by the legislature, could not even veto laws. He had to act with the approval of the Governor's Council on important matters.

Henry disagreed with how weak the governor's office was. He felt it was risky during wartime to have such a weak leader. But his ideas did not win. He had reason to regret the office's lack of power. On June 29, 1776, the convention elected him as Virginia's first post-independence governor. He won by 60 votes to 45 for Thomas Nelson Jr.. Henry was Virginia's most popular politician at the time. His election helped people accept the new government. But it also put him in a figurehead role, away from the real power in the new government, which was the House of Delegates.

Henry became ill almost immediately after being sworn in as governor on July 5. He recovered at Scotchtown. He returned to Williamsburg in September. He wrote to General Washington about the military situation. Washington complained about the state militias. He felt a Continental Army committed for the whole war was needed. Henry helped recruit new troops for Washington. But his efforts were limited by the weakness of his office. In December 1776, the General Assembly was worried that Washington's army was retreating. They gave Henry temporary expanded powers. Jefferson was still unhappy about this years later, feeling Henry was trying to become a dictator. In March 1777, Henry wrote to Washington asking to recruit soldiers for up to eight months. Washington's angry reply said such troops were not useful. Henry dropped the matter, saying he respected Washington's military experience. Recruiting remained a problem. Many Virginians would join the county militia but did not want to join the Continental Army. They feared being sent out of state or getting sick. Desertion was also a problem Henry tried to solve with little success. Many Virginians had joined with promises they would not be sent outside the state or local area. They left when orders came to march.

Henry was elected to a second one-year term without anyone running against him. He took the oath on July 2, 1777. On October 25, at Scotchtown, he married Dorothea Dandridge. She was the daughter of his old client, Nathaniel West Dandridge. This made him a closer relative to Washington, as Nathaniel Dandridge was Martha Washington's uncle. Henry had six children with Sarah Henry. He would have eleven more with Dorothea, though two died very young. She brought 12 slaves with her, adding to the 30 Patrick Henry already owned. He sold Scotchtown in 1777. He moved to Leatherwood Plantation in Henry County. The General Assembly had just created this county and named it after him.

When Washington and his troops camped at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777–78, Henry arranged for food and livestock to be sent to them. Some people were unhappy with Washington's leadership. This led to the Conway Cabal, a secret plot against him. Henry supported Washington. Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia, who was not enthusiastic about Washington, sent the governor an unsigned letter. It discussed plans against the general. Henry immediately sent the letter to Washington. It is not certain if Henry recognized Rush's handwriting, but Washington did. This warned him about the plot. President Washington wrote in 1794 that he had always respected Henry. He felt grateful for Henry sending him the anonymous writings in 1777.

To protect Virginia's large claims in the West (reaching the Mississippi River and north to present-day Minnesota) from British and Native American forces, Henry sent George Rogers Clark on an expedition in December 1777. Clark's secret mission was against Kaskaskia, a British and French settlement. His public orders just said he was to raise a militia and go to Kentucky (then part of Virginia). Clark captured Kaskaskia in July 1778. He stayed north of the Ohio River for the rest of Henry's time as governor. Although the expedition did not go as well as hoped, Henry celebrated its successes. But after he left the governorship in 1779 and was elected to the House of Delegates, he became an opponent of Clark.

Henry was elected to a third term on May 29, 1778, again without opposition. Jefferson led the group sent to tell him of his election. In December 1778, Henry urgently asked Congress for naval help to protect Chesapeake Bay. No help came. On May 8, 1779, near the end of Henry's governorship, British ships under Sir George Collier entered the bay. They landed troops and took Portsmouth and Suffolk, destroying valuable supplies. The British left on May 24. Henry, limited to three terms by the 1776 constitution, left office soon after. Jefferson succeeded him, and Henry returned to Leatherwood with his family.

Life at Leatherwood and in the House of Delegates (1779–1784)

At Leatherwood, Henry focused on local matters in the sparsely populated county. He was given seats on the county court (the local government) and on the parish vestry, as prominent landowners were. He refused to be elected a delegate to Congress. He said his personal business and past illness made it impossible.

The war effectively ended with the American victory at the siege of Yorktown. Henry served as a delegate from his county until 1784, when he was elected governor again. Peace brought many changes. Henry supported laws to reform Virginia's money and to adjust payments for old contracts from before periods of high inflation. Jefferson and others wanted to reopen contracts that had already been settled with money that had lost value. Henry thought that was unfair. Because of his influence in the General Assembly, his version of the law passed. This had international effects, as some creditors were British. They wanted payment in hard money, not the depreciated currency that had been paid into a special account.

In May 1783, Henry successfully supported a resolution to end the trade ban against Britain. This passed despite opposition from Speaker John Tyler Sr. Henry also introduced a law to allow Loyalists (people who supported Britain during the war) to return to Virginia. There was strong opposition to this. The measure was delayed until later in the year. By then, public opinion had been gathered from county meetings. Henry spoke in the debate, asking, "shall we, who have laid the proud British lion at our feet, be frightened of its whelps?" Once it was changed (though how is not clear), the bill passed in November 1783.

Henry worked with James Madison, a delegate after three years in Congress, on several issues. However, they disagreed on state support for Virginia's Protestant churches. Madison, like Jefferson, wanted a clear separation between church and state. This meant no public money for religion. But Henry believed that Christian taxpayers should pay to support the Protestant church of their choice. This would fund many churches, similar to how Anglicanism was funded in Virginia before the war. Henry was not alone in this belief; both Washington and Lee supported such plans. The General Assembly might have passed the bill. But on November 17, 1784, the legislators elected Henry as governor. Madison believed Henry took the job for family reasons. His wife and children were likely happier in Richmond than in remote Henry County. But this meant Henry's bill was delayed until the next year and eventually defeated. Instead, Madison helped pass Jefferson's Statute for Religious Freedom. This law, which required separation of church and state, passed in 1786.

Second Time as Governor (1784–1786)

Henry's second time as governor lasted two years. The legislature re-elected him in 1785. This period was generally calmer than his first. During this time, Henry and his family lived at "Salisbury" in Chesterfield County. This was about 13 miles from Richmond in the countryside. He rented this home, though he had an official residence near the Virginia Capitol, which was being built. The General Assembly had passed a law for new weapons for the militia. Henry worked with Lafayette to have them sent from France.

Each county's militia was under strong local control. This caused problems during the war. Local militias refused orders from Henry and other governors when asked to serve out of state or to draft recruits into the Continental Army. In 1784, the General Assembly passed a law to bring the militias under central control. It ended all militia officer jobs and allowed Henry, with his council's approval, to appoint replacements. The Virginia Constitution required a recommendation from the county court. Instead of asking the county court, Henry asked prominent citizens in each county whom he or his council members knew. This almost caused a revolt in the counties. Citizens protested the law as unconstitutional, and counties refused to obey. The law was largely not enforced. In October 1785, Henry asked the legislators to repeal it; they did so the next year.

People in western North Carolina, which is now Tennessee, wanted to separate and form the State of Franklin. A former delegate, Arthur Campbell, wanted to join Virginia's nearby Washington County as part of this plan in 1785. Henry removed Campbell as a militia officer and from his other county jobs. He also removed Campbell's supporters. He replaced them with loyal residents. Henry urged leniency in his report to the General Assembly that October. He said the Washington County separatists were misled by worries about the poor economy. However, he had the legislature pass a Treason Act. This law forbade setting up a rival government within Virginia territory.

Henry also worked to help Virginia grow, both as governor and through his own investments. He supported plans to open navigation on the upper Potomac and James rivers. He imagined canals connecting them to the Ohio River Valley. He also supported a plan to build a canal across the Great Dismal Swamp. He believed this would bring trade from eastern North Carolina through Norfolk. He owned land along the proposed route. He tried to get General Washington interested in the plan, but he was not successful.

Despite Henry's support for improvements, he failed to tell Virginia's representatives about their meeting with Maryland. This meeting was about navigation on the Potomac. Only two, including George Mason, attended what became known as the Mount Vernon Conference in 1785. Randolph, who could not attend because he was not told in time, hinted that Henry's neglect was not forgetfulness. He suggested it was a growing dislike for federal matters. In 1786, Henry was more careful in telling delegates about the Annapolis Conference. This conference was supported by Madison, who was appointed a delegate. Henry stepped down at the end of his fifth term. He said he needed to spend time with his family and earn money to support them. Randolph became governor after him.

Opposing the Constitution (1787–1790)

After his time as governor ended in November 1786, Henry did not want to return to distant Leatherwood. He hoped to buy land in Hanover County but bought property in Prince Edward County instead. Hampden-Sydney College, which he had helped start in 1775, is in that county. Henry enrolled his sons there. The local voters elected Henry to the House of Delegates in early 1787. He served there until the end of 1790.

Governor Randolph offered to make Henry a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. This meeting was in Philadelphia later that year. It was to consider changes to the Articles of Confederation, which had governed the states since 1777. Henry refused the appointment, saying it would be financially difficult. A famous story says that when Henry was asked why he did not go, he replied, "I smelt a rat."

Henry's past actions of urging unity made him a possible supporter of a stronger bond between the states. As late as the end of 1786, Madison hoped Henry would be an ally. But several things had made Henry distrust the Northern states. He felt Congress failed to send enough troops to protect Virginia settlers in the Ohio River Valley. Henry was very angry about the Jay–Gardoqui Treaty. This treaty would have given Spain exclusive navigation rights on the Mississippi River for 25 years. This was in exchange for trade benefits that would help New England. Northern votes were enough to change John Jay's instructions, allowing him to make the deal. Southern votes were enough to block the treaty's approval. These events made Henry and some other Virginia leaders feel betrayed. They had little trust in the North.

When the Philadelphia convention finished in September 1787, its president, Washington, returned home. He immediately sent a copy of the new Constitution to Henry, recommending he support it. Henry was in Richmond for the autumn legislative session as a delegate. He thanked Washington for leading the convention and sending the document. But he said, "I have to lament that I cannot bring my Mind to accord with the proposed Constitution. The Concern I feel on this account is really greater than I am able to express." He hinted, though, that he was still open to changing his mind. This allowed Henry to stay undecided as opponents of the Constitution, like Mason and Edmund Randolph, shared their views. He used this time to refine his own ideas.

In the first Virginia debate over the Constitution, they called for a convention to decide if the state should approve it. Henry and Mason supported allowing the convention to approve it only if changes were made. They reached a compromise. The convention members would have full freedom to decide what to do. The convention was set for June 1788, with elections in March. Both supporters and opponents felt time would help them.

Henry was easily elected to the convention from Prince Edward County. John Blair Smith, president of Hampden-Sydney College, annoyed him. Smith had students read a speech by Henry about the Constitution, and then Smith's own reply, in Henry's presence. Henry opposed the Constitution because it gave too much power to the president. He had fought to free Virginia from King George. He did not want to give such powers to someone who might become a dictator. Henry saw the Constitution as a step backward. He felt it betrayed those who died in the Revolutionary War.

At the Virginia Ratifying Convention, which began on June 2, 1788, Henry's "personality blazed in all its power and glory." Henry argued that the writers of the Constitution had no right to begin it "We the People." He said they ignored the powers of the states. He thought the document put too much power in the hands of too few. He pointed out that the Constitution, proposed without a Bill of Rights, did not protect individual rights:

Will the abandonment of your most sacred rights tend the security of your liberty? Liberty, the greatest of all earthly blessings—give us that precious jewel and you may take everything else. But I fear I have lived long enough to become an old-fashioned fellow. Perhaps an invincible attachment to the dearest rights of man may, in these refined, enlightened days, be deemed old-fashioned: if so, I am contented to be so.

Madison, the main supporter of the Constitution, was limited in replying to Henry's criticisms. He was sick for most of the convention. Henry likely knew he was fighting a losing battle. The convention was moving toward approving the Constitution. But he continued to speak at length. His speeches fill almost a quarter of the pages of the Richmond convention's debates. Governor Randolph, who had come to support approval, joked that if Henry kept arguing, the convention would last six months instead of six weeks.

After the convention voted on June 25 to approve the Constitution, Henry was somewhat pleased. The convention had proposed about 40 amendments. Some of these were later included in the Bill of Rights. Mason, Henry's ally, planned a fiery speech about the new government's flaws. He was talked out of it. One story says Henry told other opponents that he had done his duty by opposing approval. As republicans, with the issues settled democratically, they should all go home. Madison wrote to Washington that Henry still hoped for amendments to weaken the federal government. He thought they might be proposed by a second national convention.

Henry returned to the House of Delegates. There, he successfully stopped Madison's attempt to become a federal senator from Virginia. Under the original Constitution, senators were elected by state legislators, not the people. Although Henry made it clear he would not serve in office outside Virginia, he received many votes in the election. Madison was elected to the House of Representatives in a district where he was opposed by James Monroe. Madison's supporters complained that Henry's supporters in the legislature had unfairly placed Orange County, Madison's home, in a district that leaned against the Federalists. Henry also made sure that the requested amendments were included in petitions from the legislature to the federal Congress. Despite his concerns, Henry served as one of Virginia's presidential electors. He voted for Washington (elected President) and John Adams (elected Vice President). Henry was disappointed when the First Congress only passed amendments dealing with personal liberties, not those meant to weaken the government.

A final issue Henry worked on before leaving the House of Delegates at the end of 1790 concerned the Funding Act of 1790. This act had the federal government take over the states' debts, much of which came from the Revolutionary War. On November 3, 1790, Henry introduced a resolution. It was passed by the House of Delegates and the state Senate. It declared the act "repugnant to the constitution of the United States." It said the act used a power not given to the federal government. This would be the first of many resolutions passed by Southern state legislatures in the coming decades. These resolutions defended states' rights and a strict reading of the Constitution.

Later Years

After leaving the House of Delegates in 1790, Henry found himself in debt. This was partly due to expenses while governor. He tried to secure his family's wealth through land deals and by returning to law. He was not fully reconciled to the federal government. Henry thought about creating a new republic in the sparsely settled frontier lands, but his plans did not happen. He did not travel as widely for cases as he had in the 1760s. He mostly worked in Prince Edward and Bedford counties. However, for an important case or a large fee, he would travel to Richmond or over the mountains to Greenbrier County.

When the new federal court opened in Virginia in 1790, British creditors quickly filed over a hundred cases. They wanted to enforce claims from the Revolutionary War. Henry was part of the defense team in Jones v. Walker before the federal court in 1791. His co-counsel included John Marshall. Marshall prepared the written arguments, while Henry did much of the speaking in court. Henry argued the case for three days. Marshall later called him "a great orator... and much more, a learned lawyer, a most accurate thinker, and a profound reasoner." The case ended without a clear decision after one of the judges died. But the legal teams met again for the case of Ware v. Hylton. Henry's argument before another three-judge panel, which included Chief Justice John Jay and Associate Justice James Iredell, made Justice Iredell exclaim, "Gracious God! He is an orator indeed." Henry and Marshall initially won. But the plaintiffs appealed. After Marshall argued his only case before the Supreme Court, that court ruled for the British creditors in 1796.

Henry's friendship with Washington had cooled during the Constitution debates. But by 1794, both men wanted to make up. Henry found himself more aligned with Washington than with Jefferson and Madison. Washington still felt grateful to Henry for telling him about the Conway Cabal. Washington offered Henry a seat on the Supreme Court in 1794, but he refused. He felt his family needed him. Washington also tried to get Henry to accept jobs as Secretary of State and as minister to Spain. Virginia Governor "Light-Horse" Harry Lee wanted to appoint him to the Senate. Henry refused each time. Henry's continued popularity in Virginia made him an attractive ally. Even Jefferson tried to recruit him, sending word through a friend that he held no grudge. After Washington made it clear he would not seek a third term in 1796, Marshall and Lee discussed a possible Henry run for president with him. But Henry was unwilling. The General Assembly elected him as governor again that year, but he declined, citing age and health. Henry's refusal to accept these offices made him even more popular. Like Washington, he was seen as a Cincinnatus, giving up power to return to his farm.

Henry sold his property in Prince Edward County in 1792. He moved with his family to Long Island, a plantation in Campbell County. In 1794, Henry bought Red Hill near Brookneal, Virginia in Charlotte County. He and his family lived there most of the year, though they moved to Long Island during the "sickly season." Henry was pleased when his old friend John Adams was elected president in 1796 over his opponent Jefferson. But Henry's support for the Federalist Party was tested by the strict Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. He chose to say nothing but supported Marshall, a moderate Federalist, for the House of Representatives. Marshall won by a small margin. Henry was under strong pressure from Virginia Federalists to return to politics. But it was not until former President Washington urged him to run for the legislature in early 1799 that Henry agreed. He turned down an offer from President Adams to make him an envoy to France. Henry was elected as a delegate from Charlotte County on March 4, 1799.

The legislature had no immediate session planned. So he returned to Red Hill and never left again. He died there from a medical condition called intussusception on June 6, 1799. He was buried at Red Hill. In his will, Henry left his estates and his 67 slaves to be divided among his wife and his six sons. He did not free any slaves, despite his speeches against being enslaved by tyrants and his comments opposing slavery itself.

Many tributes were made to Henry after his death. The Virginia Gazette printed a death notice bordered in black. It said, "As long as our rivers flow, or mountains stand, Virginia... will say to rising generations, imitate my H E N R Y." The Petersburg Intelligencer regretted the death of a man who might have been able "to bring together all parties and create harmony." The Argus, a newspaper that supported Jefferson, noted that Henry "pointed out those evils in our Constitution... against which we now complain." It added, "If any are disposed to criticize Mr. Henry for his late political change [to supporting the Federalists], if anything has been written on that subject, let the Genius of American Independence drop a tear, and blot it out forever."

Images for kids

-

Red Hill Plantation, Charlotte County, Virginia, around 1907

-

Patrick Henry $1 stamp, Liberty issue, 1955

See also

In Spanish: Patrick Henry para niños

In Spanish: Patrick Henry para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |