Illinois campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Illinois campaign |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

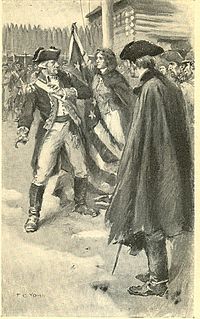

The Fall of Fort Sackville, Frederick C. Yohn, 1923 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

Illinois Regiment, Virginia State Forces Native Americans |

Detroit Militia British Army Native Americans |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| George Rogers Clark Joseph Bowman † Leonard Helm Edward Worthington |

Henry Hamilton Chevalier de Rocheblave Egushawa |

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 180 militia Native Americans: Piankeshaw Kickapoo |

145 militia 90 British regulars 60 Native Americans: Shawnee Odawa |

||||||||

The Illinois campaign was an important series of events during the American Revolutionary War. It is also known as Clark's Northwestern campaign. In this campaign, a small group of soldiers from Virginia, led by George Rogers Clark, took control of several British forts. These forts were in the Illinois Country, which is now parts of Illinois and Indiana in the Midwestern United States. This campaign is famous as a key part of the war in the western areas. It also made George Rogers Clark a well-known American hero.

In July 1778, Clark and his men crossed the Ohio River from Kentucky. They quickly took over towns like Kaskaskia and Vincennes without a fight. This was because many French-speaking people and Native Americans living there did not want to fight for the British Empire. To fight back, Henry Hamilton, the British governor in Fort Detroit, took Vincennes back with his soldiers. But in February 1779, Clark made a surprise winter march and recaptured Vincennes. He also captured Hamilton. Because of Clark's success, Virginia claimed this area and called it Illinois County, Virginia.

Many people have debated how important the Illinois campaign was. Some historians believe Clark's actions helped the United States gain a huge amount of land. This land, called the Northwest Territory, was given to the U.S. in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. Because of this, Clark was often called the "Conqueror of the Northwest." His surprise march to Vincennes became a famous story.

Contents

Why the Campaign Happened

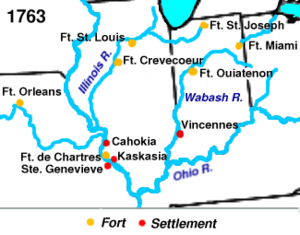

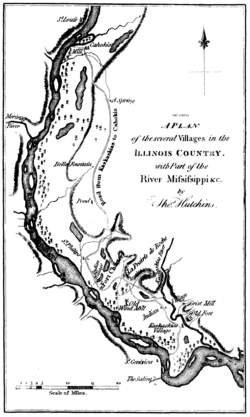

The Illinois Country was a large area that included much of today's Indiana and Illinois. Before the American Revolution, this land was part of New France. After the French and Indian War in 1763, France gave the area to the British. In 1774, the British made it part of their Province of Quebec.

In 1778, about 1,000 European settlers lived in the Illinois Country. Most spoke French. There were also about 600 African-American slaves. Thousands of Native Americans lived in villages along the Mississippi, Illinois, and Wabash Rivers. The British did not have many soldiers there. Most had been moved away to save money. A French-born soldier named Philippe-François de Rastel de Rocheblave was in charge of Fort Gage in Kaskaskia for the British. He often told his boss, Hamilton, that he needed more money and soldiers to protect the area.

When the American Revolutionary War started in 1775, the Ohio River was the border between the Illinois Country and Kentucky. Kentucky was a new area settled by American colonists. At first, the British wanted to keep Native Americans out of the war. But in 1777, Governor Hamilton was told to get Native American groups to attack the Kentucky settlements. This opened a new fighting area in the west.

In 1777, George Rogers Clark was a 25-year-old soldier in the Kentucky militia. He believed he could stop the attacks on Kentucky. His idea was to capture the British forts in the Illinois Country. Then, he wanted to move on to Detroit. In April 1777, Clark sent two spies into the Illinois Country. They reported that the fort at Kaskaskia was not well-guarded. They also said that the French-speaking people there did not care much for the British. No one expected an attack from Kentucky. Clark then wrote to Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia. He shared his plan to capture Kaskaskia.

Planning the Attack

The settlers in Kentucky did not have enough power or supplies for such a big trip. So, in October 1777, Clark traveled to Virginia. He went to meet Governor Henry. Clark shared his plan with Governor Henry and a few important Virginians. These included Thomas Jefferson and George Mason. Governor Henry was not sure at first, but Clark convinced him. The plan was approved by the Virginia government. They were only given a few details to keep the plan secret. Publicly, Clark was told to gather men to defend Kentucky. But in secret, Governor Henry told Clark to capture Kaskaskia and then decide what to do next.

Governor Henry made Clark a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia. He allowed Clark to gather seven groups of 50 men each. This group became known as the Illinois Regiment. It was part of Virginia's state army, not the main Continental Army. The men were to serve for three months once they reached Kentucky. To keep the mission secret, Clark did not tell his new soldiers that they were going to invade the Illinois Country. Clark was given money to raise men and buy supplies.

Clark set up his base at Redstone Old Fort. Three of his friends, Joseph Bowman, Leonard Helm, and William Harrod, began to recruit men. Clark was supposed to get 350 men, but it was hard to find them. Many other groups were also trying to recruit soldiers. Some people thought Kentucky should be left alone, not defended. People in other areas were more worried about different Native American groups.

Clark's Trip Down the Ohio River

Clark finally left Redstone by boat on May 12, 1778. He had about 150 new soldiers. They were in three groups led by Captains Bowman, Helm, and Harrod. Clark expected to meet 200 more men at the Falls of the Ohio in Kentucky. About 20 families also traveled with Clark's men. These families were going to settle in Kentucky.

On their trip down the Ohio River, Clark's men picked up supplies at Forts Pitt and Henry. They reached Fort Randolph soon after it had been attacked by Native Americans. The fort commander asked for Clark's help, but Clark said no. He felt he could not waste time.

Near the Falls of the Ohio, Clark learned that only a small group of the expected men had arrived. Clark sent a message asking for more recruits. Clark's boats reached the Falls of the Ohio on May 27. He set up a camp on a small island, later called Corn Island. When more men arrived, Clark added 20 of them to his force. He sent the others back to Kentucky to help defend the settlements. On the island, Clark finally told his men the real reason for their trip: to invade the Illinois Country. Most men were excited, but some left that night.

While Clark trained his soldiers, the families who came with them settled on the island. They planted corn. These settlers later moved to the mainland and started the city of Louisville. While on the island, Clark got important news: France had signed a treaty to become allies with the United States. Clark hoped this news would help him get the French-speaking people in Illinois to join his side.

Taking Over the Illinois Country

Clark and his men left Corn Island on June 24, 1778. They left behind seven soldiers who were not strong enough for the journey. Clark's force had about 175 men. They passed over the rapids during a total solar eclipse. Some men thought this was a good sign.

On June 28, the soldiers reached the Tennessee River. They landed on an island to prepare for the last part of their trip. Usually, travelers would go to the Mississippi River and then paddle upstream to Kaskaskia. But Clark wanted to surprise the British. So, he decided to march his men across what is now southern Illinois. This was a journey of about 120 miles (193 km). Clark's men captured some American hunters who had just been in Kaskaskia. These hunters gave Clark information about the village and agreed to guide them. That evening, Clark and his troops landed their boats near the ruins of Fort Massac.

The men marched 50 miles (80 km) through a forest. Then they came out into open prairie. One guide said he was lost. Clark threatened to kill him unless he found the way. The guide quickly found his way again. They arrived outside Kaskaskia on the night of July 4. The men had only brought four days of food, and they had not eaten for the last two days of their six-day march.

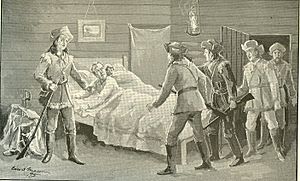

They crossed the Kaskaskia River around midnight. They quickly took over the town without firing a shot. At Fort Gage, the Virginians captured Rocheblave, who was sleeping. The next morning, Clark worked to get the townspeople to support him. This was easier because Clark brought news of the alliance between France and America. People were asked to promise loyalty to Virginia and the United States. Father Pierre Gibault, the village priest, was convinced after Clark promised that the Catholic Church would be protected. Rocheblave and others who were against the Americans were taken prisoner and sent to Virginia.

Clark soon took control of other French settlements nearby. On July 5, Captain Bowman was sent with 30 men to secure Prairie du Rocher, St. Philippe, and Cahokia. These towns did not fight back. Within 10 days, more than 300 people had promised loyalty to America. Clark then turned his attention to Vincennes. Father Gibault offered to help. On July 14, Gibault went to Vincennes. Most citizens there agreed to promise loyalty. The local soldiers guarded Fort Sackville. Gibault returned to Clark in early August. He reported that Vincennes was now on their side, and the American flag was flying at Fort Sackville. Clark sent Captain Helm to Vincennes to take command of the local soldiers.

Hamilton Takes Vincennes Back

In Detroit, Hamilton learned about Clark taking over the Illinois Country by early August 1778. He decided to take Vincennes back. Hamilton gathered about 30 British soldiers, 145 French-Canadian soldiers, and 60 Native Americans. On October 7, Hamilton's main group began the journey of more than 300 miles (483 km) to Vincennes. As they came down the Wabash River, they stopped and recruited more Native Americans. By the time Hamilton entered Vincennes on December 17, his force had grown to 500 men. As Hamilton got close to Fort Sackville, the French-Canadian soldiers under Captain Helm left. This left Helm and a few soldiers to surrender. The townspeople quickly changed their loyalty back to the British King.

After taking Vincennes back, most of the Native Americans and Detroit soldiers went home. Hamilton stayed at Fort Sackville for the winter with about 90 soldiers. He planned to take back the other Illinois towns in the spring.

Clark's Hard March to Vincennes

On January 29, 1779, Francis Vigo, a fur trader, came to Kaskaskia. He told Clark that Hamilton had taken Vincennes back. Clark decided he had to launch a surprise winter attack on Vincennes. He knew it was a risky plan. He wrote to Governor Henry, saying they had to attack Hamilton or lose the whole area.

On February 6, 1779, Clark set out for Vincennes. He had about 170 volunteers. Nearly half of them were French soldiers from Kaskaskia. Captain Bowman was second-in-command. While Clark and his men marched across the land, 40 men left in an armed boat. This boat was to be placed on the Wabash River below Vincennes. Its job was to stop the British from escaping by water.

Clark led his men across what is now Illinois, a journey of about 180 miles (290 km). It was not a very cold winter, but it rained often. The plains were often covered with several inches of water. They carried food on packhorses. They also hunted wild animals as they traveled. On February 13, they reached the Little Wabash River. It was flooded, making a stream about 5 miles (8 km) wide. They built a large canoe to move men and supplies across. The next few days were very tough. Food was running low, and the men were almost always walking through water. They reached the Embarras River on February 17. They were only 9 miles (14 km) from Fort Sackville. But the river was too high to cross. They followed the Embarras down to the Wabash River. The next day, they started building boats. Everyone was tired and hungry. Clark worked hard to keep his men from leaving.

On February 20, five hunters from Vincennes were captured. They told Clark that his army had not been seen yet. They also said that the people of Vincennes still supported the Americans. The next day, Clark and his men crossed the Wabash by canoe. They left their packhorses behind. They marched towards Vincennes, sometimes in water up to their shoulders. The last few days were the hardest. They crossed a flooded plain about 4 miles (6 km) wide. They used canoes to move tired men from one high spot to another. Just before reaching Vincennes, they met a friendly villager. He told Clark that they were still a secret. Clark sent the man ahead with a letter to the people of Vincennes. He warned them that he was about to arrive with an army. He told everyone to stay in their homes unless they wanted to be seen as enemies. The message was read in the town square. No one went to the fort to warn Hamilton.

Fighting at Fort Sackville

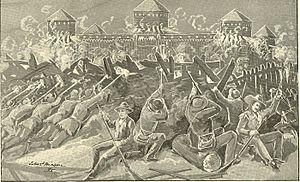

Clark and his men marched into Vincennes at sunset on February 23. They entered the town in two groups. One was led by Clark, the other by Bowman. Clark used a small hill to hide his men but let their flags be seen. This made it look like 1,000 men were coming. While Clark and Bowman secured the town, a group of soldiers began firing at Fort Sackville. A local resident, François Busseron, helped them by replacing their wet gunpowder. Hamilton did not realize the fort was under attack until one of his men was hurt by a bullet coming through a window.

Clark had his men dig a trench 200 yards (183 m) in front of the fort's gate. Men fired at the fort all night. Small groups crept up to within 30 yards (27 m) of the walls for closer shots. The British fired their cannons. They destroyed a few houses in the town but did little damage to Clark's men. Clark's men stopped the cannons by firing through the fort's openings. They killed and wounded some of the British gunners. Meanwhile, Clark got help from locals. Villagers gave him gunpowder and ammunition they had hidden from the British. Young Tobacco, a Piankeshaw chief, offered to help with his 100 men. Clark said no. He worried that in the dark, his men might mistake the friendly Piankeshaws and Kickapoos for enemy tribes.

Around 9:00 a.m. on February 24, Clark sent a message to the fort. He demanded that Hamilton surrender. Hamilton refused. The firing continued for two more hours. Then Hamilton sent out his prisoner, Captain Helm, to offer to talk. Clark sent Helm back with a demand for Hamilton to surrender completely within 30 minutes. If not, Clark would storm the fort. Helm returned before the time was up. He presented Hamilton's idea for a three-day break in fighting. Clark refused this too. But he agreed to meet Hamilton at the village church.

Before the meeting, an event happened that caused much debate later. A group of Native Americans and French-Canadians came into town. They did not know Clark had taken Vincennes and surrounded Fort Sackville. There was a fight, and Clark's men captured six of them. Two of the prisoners were French-Canadians. They were released because the villagers and one of Clark's French-Canadian followers asked for it. Clark decided to make an example of the four Native American prisoners. They were made to sit where the fort could see them, and then they were killed. Their bodies were thrown into the river. Clark wrote about these killings without saying sorry. He believed they were fair revenge for settlers killed in Kentucky. He also thought it would scare Native Americans into stopping their attacks.

At the church, Clark and Bowman met with Hamilton. They signed terms for surrender. At 10:00 a.m. on February 25, Hamilton's 79 soldiers marched out of the fort. Clark's men raised the American flag over the fort. They renamed it Fort Patrick Henry. A group of Clark's soldiers and local militia went up the Wabash River. They captured a British supply convoy. They also captured British soldiers and Philippe DeJean, Hamilton's judge from Detroit. Clark sent Hamilton, seven of his officers, and 18 other prisoners to Virginia. French-Canadians who had been with Hamilton were set free after they promised to stay neutral.

What Happened Next

Clark had high hopes after taking Vincennes back. He thought this victory would almost end the fighting with Native Americans. In the years that followed, Clark tried to plan an attack on Detroit. But each time, the plan was canceled because he did not have enough men or supplies. Meanwhile, settlers started moving into Kentucky after hearing about Clark's victory. In 1779, Virginia opened an office to record land claims in Kentucky. New settlements like Louisville were started.

After learning that Clark had first taken over the Illinois Country, Virginia claimed the area. They created Illinois County, Virginia in December 1778. In early 1781, Virginia decided to give this land to the central government. This helped lead to the final approval of the Articles of Confederation. These lands later became the Northwest Territory of the United States.

The Illinois campaign was largely paid for by local people and traders in the Illinois Country. Clark sent his receipts to Virginia, but many of these people were never paid back. Some important helpers, like Father Gibault and Francis Vigo, never got paid in their lifetime. They became poor. However, Clark and his soldiers were given land across from Louisville. This land, called Clark's Grant, is now parts of Clarksville, Indiana, and Clark and eastern Floyd County, Indiana.

In 1789, Clark began to write about the Illinois campaign. He did this because members of the United States Congress asked him to. They were deciding how to manage the Northwest Territory. Clark's story, called the Memoir, was not published while he was alive. It was fully published in 1896. This Memoir was used for two popular novels: Alice of Old Vincennes (1900) and The Crossing (1904). The United States Navy has named four ships USS Vincennes to honor the battle at Vincennes.

The discussion about whether George Rogers Clark "conquered" the Northwest Territory began after the Revolutionary War. This was when the government was trying to figure out land claims and war debts. In July 1783, Governor Benjamin Harrison thanked Clark for "taking such a great and valuable territory out of the hands of the British Enemy." Clark himself never made such a claim. He sadly wrote that he had never captured Detroit. He said, "I have lost the object." In the 1800s and early 1900s, Clark was often called the "Conqueror of the Northwest" in history books. But in the 1900s, some historians started to question this idea. They argued that Clark had to pull his troops out of the Illinois Country before the war ended because he lacked resources. Also, most Native American groups were not defeated. So, they said there was no "conquest" of the Northwest. They also argued that Clark's actions did not affect the border talks in Europe. In 1940, historian Randolph Downes wrote that it was wrong to say Clark "conquered" the Old Northwest. He said it was more accurate to say Clark helped the French and Native American people there remove themselves from British rule.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |