British Army during the American Revolutionary War facts for kids

The British Army during the American Revolutionary War fought for eight years in battles all over the world. A big defeat at the Siege of Yorktown against American and French forces led to Britain losing the Thirteen Colonies in North America. The Treaty of Paris that ended the war also meant Britain lost some things it had gained in the Seven Years' War. However, Britain won many battles elsewhere, so most of its empire stayed strong.

In 1775, the British Army was made up of volunteers. After the Seven Years' War, the army didn't get much money or new recruits. This made it quite weak when the war started in North America. To fix this, the British government quickly hired soldiers from German states. These "auxiliaries" fought alongside the regular British army starting in 1776. Britain also tried to force people into the army (called impressment) in 1778. But this was very unpopular and stopped in 1780.

The constant fighting, the Royal Navy's struggle against the French Navy, and the British army leaving North America in 1778 led to their defeat. When Cornwallis's army surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, a new political group, the Whigs, gained power in parliament. This stopped British attacks in North America.

Contents

How the Army Was Organized and Recruited

After the Seven Years' War, Britain had a huge national debt. The army had grown very large during that war. When peace came in 1763, the army got much smaller. Only about 11,000 men stayed in Great Britain. Another 10,000 were in Ireland and 10,000 in the colonies. This meant 20 infantry regiments were in Britain, 21 in Ireland, 18 in the Americas, and 7 in Gibraltar. There were also 16 cavalry regiments (6,869 men) and 2,712 artillery men. In total, this was about 45,000 soldiers, not counting the artillery.

The British government felt this wasn't enough to fight a rebellion in America. They also needed to defend other territories. So, they made agreements with German states, mainly Hesse-Kassel and Brunswick. They hired 18,000 more soldiers. Half of these were placed in garrisons to free up British units. This brought the army's total strength to about 55,000 men.

Parliament found it hard to get enough soldiers. The army was not a popular job. One big reason was the low pay. A private soldier earned only 8d. a day. This was the same pay as 130 years earlier! The pay was too low for the rising cost of living. Also, soldiers usually served for life, which didn't attract many people.

To get more volunteers, Parliament offered a reward of £1.10s for each new recruit. As the war continued, Parliament became desperate for soldiers. They offered military service to criminals to avoid jail. Deserters were also pardoned if they rejoined their units.

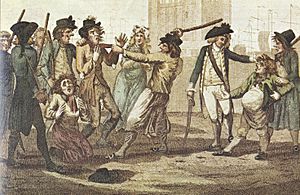

Impressment, or forcing people into service, was a common way to get recruits. But it was very unpopular. Many people joined local militias to avoid being pressed into the regular army. Sometimes, army and navy press gangs would even fight each other to get recruits. Men would hurt themselves to avoid being pressed. Many also deserted as soon as they could. Pressed men were not very reliable soldiers. Regiments with many pressed men were sent to faraway places like Gibraltar or the West Indies. This made it harder for them to desert.

After the losses at the Battles of Saratoga and the start of war with France and Spain, voluntary enlistment wasn't enough. Between 1775 and 1781, the regular army grew from 48,000 to 121,000 soldiers. In 1778, the army tried new ways to get more men. Towns and nobles helped raise 12 new regiments, totaling 15,000 men. The government also passed laws allowing limited impressment in parts of England and Scotland. But these laws were unpopular and stopped in May 1780.

The recruiting laws of 1778 and 1779 also offered better reasons to join. These included a £3 reward and the chance to leave the army after three years, unless the war continued. Thousands of volunteer militia groups were formed for home defense in Ireland and England. Some of the best of these joined the regular army. The British government even released criminals and debtors from prison if they joined the army. Three whole regiments were formed this way.

By November 1778, the army had 121,000 men. This included 24,000 foreign soldiers and 40,000 militia. The next year, the total force was about 194,000 men. This included 104,000 British soldiers, 23,000 Irish soldiers, 25,000 foreign soldiers (like the "Hessians"), and 42,000 militia.

Army Leaders

The British Army didn't have a clear command structure. Commanders often made decisions on their own. The top position, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, was empty until 1778. Then, Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst took the role. He held it until the war ended. But his job was mainly to organize forces at home. He helped against a possible invasion in 1779 and stopped the anti-Catholic riots in 1780.

The war effort was mostly directed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, George Germain, 1st Viscount Sackville. Even though he wasn't formally in the army, he chose generals, handled supplies, and planned many strategies. Some historians say he did a great job. Others say he made mistakes and struggled to control his generals.

Officer Ranks

In the mid-1700s, officers came from different social backgrounds. The Georgian army allowed more people to become officers than later armies. Officers needed to read and write. But there were no strict rules about their education or social class. Most regimental officers were not from rich, land-owning families. They were middle-class people looking for a career.

Officers could buy their ranks. This was common. The cost of a rank depended on its social and military importance. For example, ranks in the Guards regiments were very expensive. Rich people without military training sometimes bought high-ranking positions. This could make a regiment less effective.

Some senior British officers drank a lot. General William Howe was said to have many "crapulous mornings" in New York. John Burgoyne drank heavily every night near the end of the Saratoga campaign. These generals were also reported to have spent time with other officers' wives. During the Philadelphia campaign, British officers offended local Quakers by having their mistresses in the houses where they were staying.

In 1776, the British Army had 119 generals. But many were too old or sick to lead in battle. Others didn't want to fight against the colonists or serve for years in America. Britain had trouble finding strong senior leaders in America. Thomas Gage, the Commander-in-Chief in North America at the start of the war, was criticized for being too soft on the rebels. Jeffrey Amherst became Commander-in-Chief in 1778, but he refused to lead directly in America. He didn't want to take sides in the war. Admiral Augustus Keppel also refused, saying, "I cannot draw the sword in such a cause." The Earl of Effingham quit his job when his regiment was sent to America. William Howe and John Burgoyne also didn't like military solutions to the problem. Howe and Henry Clinton both said they were unwilling participants and just following orders.

Sir William Howe took over from Sir Thomas Gage as Commander-in-Chief in North America. Howe was 111th in seniority. Both Gage and Howe had led light infantry in America during the French and Indian War. But Gage was blamed for not understanding how strong the rebellion was. He was replaced in 1776. Howe had many more soldiers joining him. He was also the brother of Admiral Richard Howe, the Royal Navy's commander in America. The two brothers had much success in 1776. But they failed to destroy Washington's army. They also tried to start peace talks, but nothing came of them.

In 1777, General John Burgoyne led a big campaign south from Canada. He had early success. But he kept going despite major supply problems. He was surrounded and forced to surrender at Saratoga. This event made Britain's European rivals join the war. After Howe's Philadelphia campaign that same year didn't achieve clear results, Howe was called back. Sir Henry Clinton replaced him.

Clinton was known as a very smart expert on tactics and strategy. But he didn't want to take over from Howe. He became commander when the war grew bigger, forcing him to send troops to other places. He became bitter because the government wanted him to win the war with fewer soldiers than Howe had. He tried to resign many times. He also argued with navy commanders and his own officers.

While Clinton held New York, Lord Cornwallis led a separate campaign in the southern states. Cornwallis was one of the most aristocratic British generals in America. But he had wanted a military career since he was young. He insisted on sharing his soldiers' hardships. After early victories, he couldn't destroy the American armies or get much support from Loyalists. Clinton ordered him to create a fortified area on the Chesapeake coast. But a French fleet cut him off. He was forced to surrender at the Siege of Yorktown. This marked the end of Britain's serious attempts to retake America.

The last effective British commander in America was Sir Guy Carleton. He had defended Quebec in 1775. But he was passed over for Burgoyne in 1777 because he was seen as too careful. As commander, his main job was to keep the many Loyalists and former slaves safe in the British area of New York.

Carleton successfully managed the British withdrawal from the American coast. This started with leaving Savannah in July 1782. Then came the evacuations of Charleston, South Carolina in December 1782 and New York City in November 1783. In 1783, Britain gave Florida back to Spain in the Anglo-Spanish Treaty of Versailles. The Royal Navy helped many Loyalists move to the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Great Britain.

Army Size

Here's how big the British Army was, based on Lord North's reports. These numbers don't include the Irish army, Hanoverian soldiers, militia, or the East India Company's private army. The numbers for North America are in parentheses.

- April 1775: 27,063 (6,991)

- March 1776: 45,130 (14,374)

- August 1777: 57,637 (23,694)

- October 1778: 112,239 (52,561)

- July 1779: 131,691 (47,624)

- September 1780: 147,152 (44,554)

- September 1781: 149,282 (47,301)

- March 1782: 150,310 (47,223)

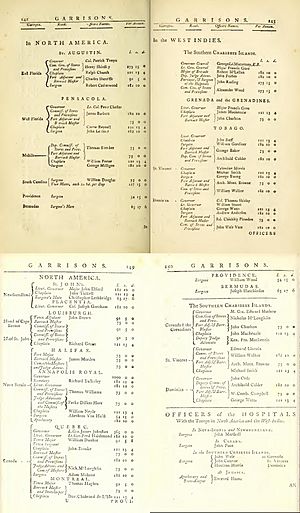

Here is a detailed list of British Army forces in North America around October 1778. About one-third of the army was not counted due to sickness, desertion, and other reasons. These numbers are only for soldiers who were ready to fight:

- New York garrison (17,452 soldiers)

- 16th and 17th Light Dragoons (two regiments)

- Guards (two battalions)

- Light Infantry (two battalions)

- Grenadiers (two battalions)

- 7th, 17th, 23rd, 26th, 33rd, 37th, 42nd, 44th, 57th, 63rd and 64th Foot regiments

- Six provincial regiments/battalions

- Queen’s Rangers regiment

- 13 Hessian regiments plus Jäger

- Expedition for West Indies (5,147 soldiers)

- 4th, 5th, 15th, 27th, 28th, 35th, 40th, 46th, 49th and 55th Foot regiments

- Embarked for East Florida (3,657 soldiers)

- 71st Foot regiment

- Five provincial regiments/battalions

- Two Hessian regiments

- Embarked for West Florida (1,102 soldiers)

- Two provincial regiments

- Waldeck regiment

- Embarked for Halifax (646 soldiers)

- One provincial regiment

- One Hessian regiment

- Rhode Island garrison (5,740 soldiers)

- 22nd, 38th, 43rd and 54th Foot regiments

- Two provincial regiments

- Four Hessian and two Anspach regiments

Infantry Soldiers

Infantry, or foot soldiers, were the main part of the British forces during the war. Two regiments, the 23rd and the 33rd, became famous for being very skilled and professional.

In the mid-1700s, army uniforms were very fancy. Movements in battle were slow and complicated. But fighting in North America during the French and Indian War changed their tactics and clothing. In battle, redcoats usually formed in two lines instead of three. This made them faster and gave them more firepower. During the American Revolution, they adapted even more. They fought in looser lines, a tactic called "loose files and American scramble." Soldiers stood further apart. They used three "orders" to change the distance between them: "order" (two spaces), "open order" (four spaces), and "extended order" (ten spaces). British infantry would advance quickly and fight with bayonets. This new way of fighting made the British army more flexible. However, some British officers later blamed this looser formation for defeats, like the Battle of Cowpens. In that battle, British troops fought against denser lines of American soldiers.

The hired German regiments that joined Howe's army in 1776 also used the two-line formation. But they kept their traditional close-order fighting style throughout the war.

Light Infantry Units

In 1758, Thomas Gage, then a lieutenant colonel, created an experimental light infantry regiment. It was called the 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot. This was one of the first such units in the British army. Other officers, like George Howe, also trained their regiments to be light infantry. When General Jeffery Amherst became commander-in-chief in North America in 1758, he ordered every regiment to form light infantry companies. The 80th regiment was disbanded in 1764. Other temporary light infantry units went back to being regular "line" units. But infantry regiments kept their light companies until the mid-1800s.

In 1771–72, the British army started a new training plan for light infantry. Much of the early training wasn't good enough. Officers weren't sure how to use light companies. Many bright young officers left light companies because being a "light-bob" officer didn't have much social status. In 1772, General George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend wrote a guide for training light companies. It also gave advice for tactics like skirmishing in rough terrain. Townshend also introduced a new way for light infantry officers to communicate. They used whistle signals instead of drums to tell troops to advance, retreat, spread out, or come closer.

In 1774, William Howe wrote the Manual for Light Infantry Drill. He formed an experimental Light Infantry battalion. This became the model for all regular light infantry in North America. Howe's system focused on creating larger groups of light infantry. These were better for big campaigns in North America, not just individual companies. When Howe took command in America, he ordered every regiment to form a light infantry company if they hadn't already. These men were usually chosen from the fittest and most skilled soldiers.

Light infantry companies from several regiments were often combined into larger light infantry battalions. Similar battalions were formed from the grenadier companies of line regiments. Grenadiers were historically chosen from the tallest soldiers. But like light infantry, they were often selected from the most skilled soldiers in their units.

Battle Tactics

At the Battle of Vigie Point in 1778, British infantry veterans of colonial fighting caused many casualties. They fought a much larger force of French troops who advanced in columns.

One description explains how "light infantry, well led by their officers, were very important. They fired on French columns from behind cover. When the French tried to spread out, they were threatened with bayonet charges. When the French advanced, the light infantry fell back to prepare for more skirmishes and ambushes."

Another account says: "Advancing in skirmish order and staying hidden, the light companies fired very destructively on the heavy French columns. Finally, one of the enemy's battalions gave way. The light companies followed them to finish the rout with bayonets."

Loyalist Fighters

Many scouts and skirmishers were also formed from Loyalists and Native Americans. The famous Robert Rogers formed the Queen's Rangers. His brother James Rogers led the King's Rangers. Loyalist pioneer John Butler raised the provincial regiment known as Butler's Rangers. They fought heavily in the Northern colonies. They were accused of being part of massacres led by Native Americans at Wyoming and Cherry Valley. Most Native Americans supported the British. Mohawk leader Joseph Brant commanded Iroquois and Loyalists in New York. Colonel Thomas Brown led another group of King's Rangers in the Southern colonies. They defended East Florida, raided the southern frontier, and helped conquer the southern colonies. Colonial Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore raised a regiment of freed slaves called the Ethiopian Regiment. They fought in the early parts of the war.

Loyalist units were very important to the British. They knew the local land well. One of the most successful units was formed by an escaped slave. He was a veteran of the Ethiopian Regiment known as Colonel Tye. He led the "Black Brigade" in many raids in New York and New Jersey. They cut off supply lines, captured rebel officers, and killed suspected leaders. He died from wounds in 1780.

Uniforms and Gear

The standard British army uniform was the traditional red coat. They wore cocked hats, white breeches, and black gaiters with leather knee caps. Hair was usually cut short or tied in plaits. As the war went on, many regiments replaced their cocked hats with slouch hats. A line infantryman's full "marching order" was very heavy. Soldiers often dropped much of their equipment before battle. Soldiers also got greatcoats for bad weather. These were often used as tents or blankets. Drummers usually wore colors opposite to their regiment's color. They carried their colonel's coat of arms and wore tall mitre caps. Most German regiments wore dark blue coats. Cavalry and Loyalists often wore green.

Grenadiers often wore bearskin hats. They usually carried cavalry sabers as a side arm. Light infantry wore short coats without lace. They had an ammunition box with nine cartridges across their stomach for easy access. They did not use bayonets but carried naval boarding axes.

The most common infantry weapon was the Brown Bess musket with a fixed bayonet. However, some light companies used short-barrel muskets or the Pattern 1776 Rifle. The British army also tried using the breech-loading Ferguson Rifle. But it was too hard to make many of them. Major Patrick Ferguson formed a small experimental company of riflemen with this weapon. But it was disbanded in 1778. Often, British forces relied on Jagers from the German troops to be skirmishers with rifles.

Regimental Flags

British infantry regiments had two flags: the King's Colour (the Union flag) and their regimental colour. The regimental colour showed the regiment's facing color. In 18th and 19th century wars, "the colours" often became a rallying point in the toughest battles. Both flags were highly respected and a source of pride for each regiment.

However, because of the way the war was fought in America, British regiments likely only used their colors for ceremonies. This was especially true for armies led by Howe and Cornwallis. But in the early years of the war, the Hessians continued to carry their colors in campaigns. Major-General Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg wrote that the British only had their colors when resting. But the Hessians carried theirs everywhere. He noted that the country was bad for fighting. He worried about the colors because regiments couldn't stay together in an attack due to walls, swamps, and cliffs. He said the English couldn't lose their colors because they didn't carry them. During the Saratoga campaign, Baroness Riedesel, a German officer's wife, saved the Brunswick regiments' colors. She burned the staffs and hid the flags in her mattress.

Daily Life in the Army

The long distance between the colonies and Britain made it hard to get supplies. The army often ran out of food and supplies. Soldiers had to live off the land. Soldiers spent a lot of time cleaning their clothes and equipment.

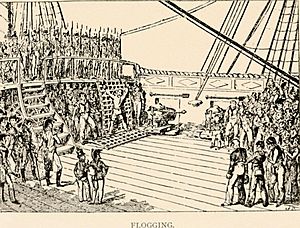

Life in the army was very tough. Discipline was strict. Crimes like theft or desertion could lead to hanging. Punishments like lashings were done in public. For example, two redcoats received 1,000 lashes each for robbery during the Saratoga campaign. Another got 800 lashes for hitting an officer. Flogging was even more common in the Royal Navy.

Despite strict rules, soldiers often lacked self-control. They loved gambling so much that they would bet their own uniforms. Many drank a lot. This was true for all ranks. The army often had poor discipline away from the battlefield. Gambling and heavy drinking were common. However, reports from American civilians said that British troops generally treated non-combatants well. Soldiers' families were allowed to join them in the field. Wives often washed, cooked, mended uniforms, and served as nurses during battles or sickness.

Soldier Training

Training was tough. Firing, bayonet drills, movements, physical exercise, marching, and forming lines were all part of the daily routine. This prepared them for campaigns.

During the war, the British army held large practice battles. These took place at Warley and Coxheath camps in southern England. The main reason was to prepare for a possible invasion. These camps were huge, with over 18,000 men. One militia officer wrote in August 1778: "We often march in large groups to nearby open lands. We are escorted by artillery. There, we practice various movements, maneuvers, and firings of a battlefield. In these trips, there is much hard work and some danger. The grandest and most beautiful imitations of action are shown to us daily. Believe me, the army generally loves war more and more." The maneuvers at Warley camp were painted by Philip James de Loutherbourg. His painting, Warley Camp: The Mock Attack, 1779, shows the uniforms of light infantry and grenadiers. These are some of the most accurate pictures of 18th-century British soldiers.

Cavalry Units

Cavalry, or horse soldiers, played a smaller role in the British army than in other European armies. Britain did not have armored Cuirassiers or Heavy cavalry. British strategy preferred medium cavalry and light dragoons. The cavalry had three Household Cavalry regiments, seven Dragoon Guards regiments, and six Light Dragoons regiments. Several hundred cavalry officers and soldiers who stayed in Britain volunteered for service in America. They transferred to infantry regiments.

Because it was hard to move supplies in North America, cavalry played a limited role. Transporting horses by ship was very difficult. Most horses died during the long journey. Those that survived usually needed weeks to recover after landing. The British army mainly used small numbers of light dragoons. They worked as scouts and were used a lot in special operations. One successful unit was the British Legion. It combined light cavalry and light infantry. They carried out raids into enemy territory.

The lack of cavalry greatly affected how the war was fought. British forces could not fully use their victories. For example, they couldn't chase down American armies after battles like Long Island and Brandywine. Without a large cavalry force to follow the infantry, retreating American forces often escaped.

Foreign Soldiers in British Service

When the war started, Britain had trouble finding enough soldiers. So, the British government hired many German soldiers. Most came from Hesse-Cassel. Units were sent by Count William of Hesse-Hanau, Duke Charles I of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Prince Frederick of Waldeck, Margrave Karl Alexander of Ansbach-Bayreuth, and Prince Frederick Augustus of Anhalt-Zerbst.

About 9,000 Hessians arrived with Howe's army in 1776. They served with British forces in New York and New Jersey. In total, 25,000 hired foreign soldiers fought with Britain during the war.

The German units had different tactics than the regular British troops. Many British officers thought the German regiments were slow. So, British generals used them as heavy infantry. This was mainly because German officers didn't want to use loose formations. British Lieutenant William Hale noted the limits of German tactics: "I believe them steady, but their slowness is a big problem in a country almost covered with woods. And against an enemy whose main skill is running from fence to fence. They keep up an irregular, but annoying fire on troops who advance at the same pace as in their training. At Brandywine, when the first line formed, the Hessian Grenadiers were close behind us. They started beating their march at the same time as us. From that minute, we didn't see them again until the action was over. Only one of them was wounded, by a random shot that came over us."

The Hessians fought in most of the major battles of the war. Duke Karl I provided Britain with almost 4,000 foot soldiers and 350 dragoons. These were led by General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel. These soldiers made up most of the German regulars under General John Burgoyne in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. They were usually called "Brunswickers." The combined forces from Braunschweig and Hesse-Hanau were nearly half of Burgoyne's army.

The Jagers were highly valued by British commanders. Their skill in skirmishing and scouting meant they continued to serve in the Southern campaigns under Cornwallis until the end of the war.

Soldiers from Hanover also served in garrisons at Gibraltar and Minorca. Two regiments fought in the Siege of Cuddalore.

Besides hired troops, the Company army in India had regular British troops and native Indian Sepoys. Foreigners were also among the regular British officers. The Swiss-born Major-General Augustine Prévost successfully defended Savannah in 1779. The former Jacobite officer Allan Maclean of Torloisk had served in the Dutch army. He was second in command during the successful defense of Quebec in 1775. Another Swiss-born officer, Frederick Haldimand, served as Governor of Quebec later in the war. Huguenots and exiled Corsicans also served among the regular soldiers and officers.

War Campaigns

Boston 1774–75

"The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month." —General Howe, March 5, 1776

British troops had been in Boston since 1769. Tensions were rising between the colonists and the British Parliament. General Thomas Gage sent an expedition to remove gunpowder from a magazine in Massachusetts on September 1, 1774. The next year, on April 18, 1775, General Gage sent 700 more men. Their goal was to seize weapons stored by the colonial militia at Concord. The Battles of Lexington and Concord were fought.

The British troops in Boston were not experienced. By the time the redcoats marched back to Boston, thousands of militiamen had gathered. A running battle followed. The British suffered many casualties before reaching Charlestown. The British army in Boston was then surrounded by thousands of colonial militia. On June 17, British forces, now led by General William Howe, attacked and took the Charlestown peninsula in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Howe achieved his goal, but the British suffered heavy losses. Both sides were stuck until guns were placed on the Dorchester Heights. At that point, Howe's position was too dangerous, and the British left Boston entirely.

Canada 1775-76

After capturing Fort Ticonderoga, American forces led by General Richard Montgomery invaded British-controlled Canada. They surrounded and captured Fort Saint-Jean. Another army moved on Montreal. However, they were defeated at the Battle of Quebec. British forces under General Guy Carleton then launched a counter-invasion. They drove the colonial forces completely out of the province. They reached all the way to Lake Champlain. But they did not recapture Fort Ticonderoga.

New York and New Jersey 1776

"I cannot too much commend Lord Cornwallis's good services during this campaign, and particularly the ability and conduct he displayed in the pursuit of the enemy from Fort Lee to Trenton, a distance exceding [sic] eighty miles, in which he was well supported by the ardour of his corps, who cheerfully quitted their tents and heavy baggage as impediments to their march." —General Howe, December 20, 1776

After leaving Boston, Howe immediately prepared to take New York. New York was seen as key to the colonies. In late August, 22,000 men (including 9,000 Hessians) landed quickly on Long Island. They used flat-bottomed boats. This was the largest water landing operation by the British army until the Normandy landings almost 200 years later. In the Battle of Long Island on August 27, 1776, the British outflanked the Americans. They pushed the Americans back to the Brooklyn Heights forts. General Howe didn't want to risk his men in a bloody frontal attack. So, he started to lay siege works. The navy failed to properly block the East River. This left an escape route open for Washington's army. Washington used this, managing a nighttime retreat through his unguarded rear to Manhattan Island.

British forces then fought a series of battles to control Manhattan Island. This ended with the Battle of Fort Washington. Nearly 3,000 Continental troops were captured. After taking Manhattan, Howe ordered Charles Cornwallis to "clear the rebel troops from New Jersey without a major fight, and to do it quickly before the weather changed." Cornwallis's force drove Washington's army entirely out of New Jersey and across the Delaware River. However, early on December 26, Washington crossed back into New Jersey. He captured a Hessian garrison at Trenton. Several days later, Washington outsmarted Cornwallis at Assunpink Creek. He then overwhelmed a British outpost at Princeton on January 3, 1777. Cornwallis regrouped and again drove Washington away. But these defeats showed the British army was too spread out. Howe abandoned most of his outposts in New Jersey.

Saratoga 1777

"I fear it bears heavy on Burgoyne ... If this campaign does not finish the war, I prophesy that there is an end of British dominion in America." —General Henry Clinton, July, 1777

After the New York and New Jersey campaign failed to win a decisive victory, the British army tried a new strategy. Two armies would invade from the north to capture Albany. One army of 8,000 men (British and Germans) was led by General John Burgoyne. Another army of 1,000 men (British, German, Indian, Loyalists, Canadians) was led by Brigadier General Barry St. Leger. A third army under General Howe would advance from New York to support them.

Due to poor planning and unclear orders, the plan failed. Howe believed he couldn't support a Northern army until Washington's army was dealt with. So, he moved on Philadelphia instead. Burgoyne's campaign started well. He captured forts Crown Point, Ticonderoga, and Anne. However, part of his army was destroyed at Bennington. After winning a tough battle at Freeman's Farm, with heavy losses, Burgoyne complained about his soldiers' inexperience. He said his men were too eager and uncertain in their aim. He also said his troops stayed in position to exchange fire too long, instead of using bayonets. After the battle, he ordered his army to retrain.

Burgoyne wanted to keep attacking. He immediately planned a second assault for the next morning. But his officer General Fraser advised him that the British light infantry and Grenadiers were tired. A new attack after more rest would be stronger. That night, Burgoyne heard that Clinton would launch his own attack. This news convinced Burgoyne to wait. He thought American General Gates would have to send some of his forces to fight Clinton. However, Gates was getting more and more soldiers. Burgoyne launched his second attempt to break through American lines early the next month. It failed at Bemis Heights. Burgoyne's force could not handle the losses. Burgoyne was finally forced to surrender after it became clear he was surrounded.

Burgoyne's campaign tactics were heavily criticized. His army was mixed and disorganized. His decision to bring too much artillery, expecting a long siege, meant his army couldn't move fast enough through the difficult land. This gave the Americans too much time to gather a huge force against him. The defeat had big consequences. The French, who had been secretly helping the colonists, decided to openly support the rebellion. They declared war on Britain in 1778.

Philadelphia 1777–78

"...I do not think that there exists a more select corps than that which General Howe has assembled here. I am too young and have seen too few different corps, to ask others to take my word; but old Hessian and old English officers who have served a long time, say that they have never seen such a corps in respect to quality..." —Captain Muenchhausen, June, 1777

While Burgoyne invaded from the North, Howe took an army of 15,000 men (including 3,500 Hessians) by sea to attack Philadelphia. Howe quickly outflanked Washington at the Battle of Brandywine. But most of Washington's army managed to escape. After some fighting with Washington's army at the Battle of the Clouds, a British light infantry battalion made a surprise attack. They attacked an American camp at the Battle of Paoli. They used bayonets instead of muskets to be quiet. This attack removed all remaining resistance to Howe. The rest of Howe's army marched on the rebel capital without opposition.

Capturing Philadelphia did not turn the war in Britain's favor. Burgoyne's army was left alone with only limited support from Sir Henry Clinton. Clinton was responsible for defending New York. Howe stayed in Philadelphia with 9,000 troops. Washington attacked him heavily, but at the Battle of Germantown, Washington was driven off. After an unsuccessful attempt to capture Fort Mifflin, Howe eventually took the forts of Mifflin and Mercer. After checking Washington's forts at the Battle of White Marsh, he returned to winter quarters. Howe resigned soon after, complaining he hadn't been supported enough. Command went to Clinton. After France declared war, Clinton followed orders to move the British army from Philadelphia to New York. He did this by marching overland, fighting a large battle at Battle of Monmouth along the way.

Raids 1778–79

In August 1778, a combined French and American attempt to drive British forces from Rhode Island failed. One year later, an American expedition to drive British forces from Penobscot Bay also failed. In the same year, Americans launched a successful expedition to drive Native Americans from the New York frontier. They also captured a British outpost in a nighttime raid. During this time, the British army carried out many successful raids. They took supplies and destroyed military defenses, outposts, stores, weapons, barracks, shops, and houses.

Southern Colonies 1780–81

"Whenever the Rebel Army is said to have been cut to pieces it would be more consonant with truth to say that they have been dispersed, determined to join again... in the meantime they take oaths of allegiance, and live comfortably among us, to drain us of our monies, get acquainted with our numbers and learn our intentions." —Brigadier General Charles O’Hara, March, 1781

The first major British operation in the Southern colonies was in 1776. A force under General Henry Clinton unsuccessfully attacked the fort at Sullivan's Island. In 1778, a British army of 3,000 men under Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell successfully captured Savannah. This began a campaign to bring Georgia under British control. A French and American attempt to retake Savannah in 1779 failed.

In 1780, the main British focus shifted to the south. British planners wrongly believed many Loyalists lived in the southern colonies. They thought a large Loyalist army could be raised to occupy areas that British troops had pacified. In May 1780, an army of 11,000 men under Henry Clinton and Charles Cornwallis captured Charleston. They also captured 5,000 Continental army soldiers. Soon after, Clinton returned to New York. He left Cornwallis with fewer than 4,000 men. Cornwallis was ordered to secure control of the southern colonies.

At first, Cornwallis was successful. He won a big victory at the Battle of Camden and swept away most resistance. However, dwindling supplies and increasing attacks by local fighters slowly wore down his troops. The destruction of a Loyalist force under Major Ferguson at King's Mountain ended hopes for large-scale Loyalist support. In January 1781, Tarleton's cavalry force was destroyed at the Battle of Cowpens. Cornwallis then decided to destroy the Continental army under Nathanael Greene. Cornwallis invaded North Carolina and chased Greene for hundreds of miles. This became known as the "Race to the Dan." Cornwallis's tired army met Greene's army at Battle of Guilford Court House. Although Cornwallis won, he suffered heavy losses. With little hope of reinforcements from Clinton, Cornwallis decided to move out of North Carolina and invade Virginia. Meanwhile, Greene moved back into South Carolina and began attacking the British outposts there.

Yorktown 1781

"If you cannot relieve me very soon, you must prepare to hear the worst." — General Charles Cornwallis, September 17, 1781

In early 1781, the British army began raiding Virginia. The former Continental army officer, Benedict Arnold, now a British brigadier, led a force with William Phillips. They raided and destroyed rebel supply bases. Arnold later occupied Petersburg and fought a small battle at Blandford.

When Cornwallis heard British forces were in Virginia, he believed North Carolina couldn't be controlled unless its supply lines from Virginia were cut. So, he decided to join forces with Phillips and Arnold. Cornwallis's army fought a series of skirmishes with rebel forces led by Lafayette. Then, he fortified himself with his back to the sea. He believed the Royal Navy could control the Chesapeake Bay. He then asked Clinton for supplies or evacuation. The reinforcements took too long to arrive. In September, the French fleet successfully blocked Cornwallis in Chesapeake Bay. Royal Navy Admiral Graves believed the threat to New York was more important and withdrew. Cornwallis then became surrounded by armies led by Washington and the French General Rochambeau. Outnumbered and with no way to get help or escape, Cornwallis was forced to surrender his army.

West Indies 1778–83

In 1776, an American force captured the British island of Nassau. After France joined the war, many poorly defended British islands fell quickly. In December 1778, veteran British troops under General James Grant landed in St. Lucia. They successfully captured the island's high ground. Three days later, 9,000 French reinforcements landed and tried to attack the British position. However, they were pushed back with heavy losses. Despite this victory, many other British islands fell during the war.

On April 1, 1779, Lord Germain told Grant to set up small garrisons throughout the West Indies. Grant thought this was unwise. Instead, he focused defenses to cover the major naval bases. He placed the 15th, 28th, and 55th Foot regiments, and 1,500 gunners at Saint Kitts. The 27th, 35th, and 49th Foot regiments, and 1,600 gunners defended Saint Lucia. Meanwhile, the royal dockyard at Antigua was held by an 800-man garrison from the 40th and 60th Foot regiments. Grant also reinforced the fleet with 925 soldiers. Although Britain lost other islands, his plans helped the British succeed in the Caribbean during the final years of the war.

East Indies 1778–83

In 1778, British forces began attacking French areas in India. First, they captured the French port of Pondicherry. Then, they seized the port of Mahé. The Mysorean ruler Hyder Ali, an important ally of France, declared war on Britain in 1780. Ali invaded Carnatic with 80,000 men. He laid siege to British forts in Arcot. A British attempt to relieve the siege ended badly at Pollilur. Ali continued his sieges, taking fortresses. Then, another British force under General Eyre Coote defeated the Mysoreans at Porto Novo. Fighting continued until 1783. The British captured Mangalore, and the Treaty of Mangalore was signed. This treaty returned both sides' lands to how they were before the war.

Gulf Coast 1779–81

From 1779, the Governor of Spanish Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, led a successful attack. He conquered British West Florida. This ended with the Siege of Pensacola in 1781.

Central America 1779–80

Britain tried twice to capture Spanish land in Central America. Once in 1779 at the Battle of San Fernando de Omoa. And again in 1780 in the San Juan Expedition. In both cases, initial British military success was defeated by tropical diseases. The San Juan Expedition had the highest British death toll of the war, with 2,500 dead.

The Spanish repeatedly attacked British settlements on the Caribbean coast. But they failed to drive them out. The British under Edward Despard succeeded in retaking the Black River settlement in August 1782. The entire Spanish force surrendered.

Europe 1779–83

Europe was the site of three of the biggest battles of the entire war. French and Spanish forces first tried to invade England in 1779. But they failed due to bad luck and poor planning. They then succeeded in capturing Minorca in 1781. But the largest of them all was the unsuccessful attempt to capture Gibraltar. By 1783, this siege involved over 100,000 men, and hundreds of guns and ships. In September 1782, the "Grand Assault" on the surrounded Gibraltar garrison took place. This was the largest single battle of the war. It involved over 60,000 soldiers, sailors, and marines. France also tried twice to capture the British Channel Island of Jersey. First in 1779 and again in 1781.

After the War

After the Treaty of Paris, the British army began leaving its remaining posts in the Thirteen Colonies. In mid-August 1783, General Guy Carleton began the evacuation of New York. He told the President of the Continental Congress that he was moving out refugees, freed slaves, and military personnel. More than 29,000 Loyalist refugees left the city.

Many Loyalists moved to Nova Scotia, British East Florida, the Caribbean, and London. The Loyalist refugees from New York City included 29,000 white Loyalists and over 3,000 Black Loyalists. Later, Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia, Canada, Jamaica, and the Black Poor of London helped found the British colony of Sierra Leone in West Africa.

The British army became much smaller again in peacetime. Morale and discipline became very poor. The number of troops fell. When the wars with France started again in 1793, the army had only 40,000 men. The army became full of corruption and inefficiency.

Many British officers returned from America believing in the power of firearms and formations with more firepower. However, officers who had not served in America wondered if the loose fighting style used in America was good for future wars against European powers. In 1788, the British army was reformed by General David Dundas. He was an officer who had not served in America. Dundas wrote many training manuals adopted by the army. The first was Principles of Military Movements. He chose to ignore the light infantry and flank battalions that the British army had come to rely on in North America. Instead, after seeing Prussian army maneuvers in Silesia in 1784, he pushed for well-drilled battalions of heavy infantry. He also pushed for uniform training, stopping colonels from developing their own training systems. Charles Cornwallis, an experienced "American" officer who saw the same maneuvers in Prussia, wrote negatively about them. He said, "their maneuvers were such as the worst general in England would be hooted at for practicing; two lines coming up within six yards of one another and firing until they had no ammunition left, nothing could be more ridiculous." The failure to officially learn from the American War of Independence contributed to the early problems the British army faced during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Images for kids

-

A press gang forcing men into military service in 1780.

-

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst, the top army leader from 1778-1782.

-

Sir William Howe, British Commander in North America, 1775–1778.

-

Sir Henry Clinton, British Commander, 1778–1782.

-

A Grenadier of the 40th Regiment of Foot in 1767.

-

British bayonet charges were very effective, as shown in this Trumbull painting of the Battle of Princeton.

-

Joseph Brant led Native Americans and Loyalists in the North.

-

Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton led the British Legion in the Southern colonies.

-

Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen commanded Hessian forces in North America.

-

British assault on Battle of Bunker Hill.

-

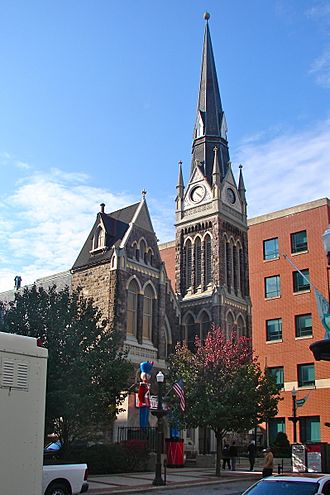

In September 1777, the Liberty Bell was hidden in this Allentown, Pennsylvania church.

-

The October 1777 surrender of General Burgoyne's army at Saratoga.

-

The death of General Johann de Kalb at the Battle of Camden.

-

The surrender of General Cornwallis's army at Yorktown.