Battle of White Marsh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of White Marsh |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

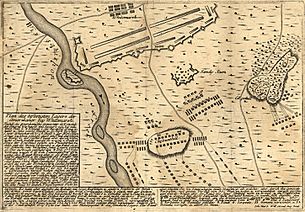

View from the British positions at the Battle of White Marsh. Ink on paper, by cartographer Johann Martin Will |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,500 | 10,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 killed and wounded 54 captured |

19 killed 60 wounded 33 missing 238 deserted |

||||||

The Battle of White Marsh or Battle of Edge Hill was an important event during the American Revolutionary War. It happened from December 5 to 8, 1777, near Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania. This series of small fights was the last big clash between British and American forces in 1777.

After a defeat at the Battle of Germantown, George Washington, who led the American army, set up camp north of British-controlled Philadelphia. His army built strong defenses on hills between Old York Road and Bethlehem Pike. From here, Washington watched the British army closely.

On December 4, General Sir William Howe, the British commander, led about 10,000 troops out of Philadelphia. He hoped to defeat Washington's army before winter arrived. After some smaller fights, Howe decided to stop his attack. He returned to Philadelphia without a major battle. This allowed Washington to move his troops to Valley Forge for the winter.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Armies Prepare for Winter

After their loss at Germantown in October 1777, Washington's army moved to different camps. They gathered supplies and waited to see what the British would do. By late October, Washington's army had about 8,300 regular soldiers and 2,700 militia (citizen soldiers).

On November 2, Washington moved his army to White Marsh, about 13 miles (21 km) northwest of Philadelphia. Here, the American soldiers began building redoubts (small forts) and other defenses. They also set up abatis (barriers made of sharpened tree branches) in front of their camp.

More American troops joined Washington from the north, including soldiers from Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia. Colonel Daniel Morgan's skilled rifle corps also arrived. Despite these new soldiers, the army faced tough times. Many soldiers lacked shoes, blankets, and warm clothes. Washington even offered a reward for the best homemade shoes.

Meanwhile, the British in Philadelphia were also getting ready. Captain John Montresor, a British engineer, built strong defenses around the city. The British also gained more soldiers, including Loyalist (Americans who supported Britain) groups. By mid-November, the British had full control of the Delaware River, allowing more supplies and 2,000 additional soldiers to reach Philadelphia.

Tensions Rise

The two armies were camped just miles apart, leading to many small fights. These skirmishes became more intense through November. Both sides lost soldiers almost daily. In response, General Howe ordered his troops to burn several large country houses near Germantown. Eleven houses were burned, and people in Philadelphia watched from rooftops.

By early December, Howe decided to try one last time to destroy Washington's army. He began planning a surprise attack. However, Washington had a spy network in Philadelphia. A Quaker woman named Lydia Darragh reportedly overheard British officers planning the attack in her home. She managed to warn the Americans. Thanks to this warning, the Continental Army was ready when Howe marched out of Philadelphia on December 4 with about 10,000 men.

The Battle Begins

Day One: December 5

Just after midnight on December 5, British troops, led by Lord Cornwallis, clashed with an American cavalry patrol. The American patrol quickly sent a message to Washington, warning him of the British movement. As the main British force marched through nearby towns, American alarm cannons fired, and soldiers took their positions.

At 3:00 AM, the British stopped on Chestnut Hill, just south of the American defenses. They waited for daylight. Washington ordered his troops to build more campfires to make their army look much larger than it was. A Hessian (German soldier fighting for the British) officer noted, "it looked as if fifty thousand men were encamped there."

Washington prepared for a fight. He sent his heavy baggage north and dispatched troops to find out the size of the British army. General James Irvine led 600 Pennsylvania militia through the Wissahickon Valley. Another group of about 1,000 Pennsylvania militia and 200 Connecticut soldiers moved to support Irvine.

Around noon, Irvine's men met the British light infantry on Chestnut Hill. The American militia fired first but were quickly forced to retreat. General Irvine was wounded and captured while trying to rally his men. The Connecticut soldiers fought briefly, killing three British soldiers and wounding eleven.

The British continued their advance and captured St. Thomas Episcopal Church on a small hill. General Howe climbed the church's bell tower to view the American positions. He decided that Washington's defenses were too strong for a direct attack. Howe's cannons tried to shell the American lines, but they couldn't reach. The British camped on Chestnut Hill that night, planning a new attack.

Day Two and Three: December 6-7

On December 6, both armies watched each other across the Wissahickon Valley. Howe hoped Washington would leave his strong positions to attack. But Washington chose to wait for the British to make the next move. By the end of the day, Howe decided to try a flanking move, attacking the American left side.

Early on December 7, Howe's army marched back through Germantown and then to Jenkintown. Washington learned of this movement around 8:00 AM. He quickly sent Morgan's Rifle Corps and Maryland militia to protect his left flank. Other American troops moved toward Edge Hill.

General Charles Grey led a British column toward the American center. He was supposed to wait for Howe's signal, but he grew impatient and attacked on his own. As Grey's troops advanced, they faced American militia on Edge Hill. The militia were quickly defeated, with some killed and captured.

The Pennsylvania militia fled in panic down Edge Hill. The Connecticut soldiers also retreated in disorder. The British pursued them close to the main American camp before falling back.

Meanwhile, Morgan's Rifle Corps and the Maryland militia faced Howe's main force in thick woods. They fought in an "Indian style," using trees for cover. The Maryland militia fought bravely, surprising British officers who were used to militia running away. However, Morgan's troops were outnumbered and had to retreat back to the main American camp.

British Withdrawal

On the morning of December 8, British generals looked at the American defenses again. To everyone's surprise, General Howe decided to pull back and return to Philadelphia. Even though his troops had won two smaller fights, his plan to get around the American flank hadn't worked as he hoped. Also, his troops were running low on supplies, and the nights were getting colder.

Around 2:00 PM, the British began their withdrawal. They lit many campfires, just like Washington had done, to hide their movements. An American scouting party, led by Captain McLane, discovered that Howe was marching back to Philadelphia. Morgan's troops harassed the British rear guard, especially General Grey's column, which was slowed by its heavy cannons. The British finally arrived in Philadelphia later that day.

Aftermath

Washington was disappointed that he couldn't force a bigger battle. He wrote to Congress that he wished the British had attacked. He believed his army's strong position would have led to an American victory. However, he also knew it would have been too risky for his army to leave their defenses and attack the British.

On December 11, the Continental Army left White Marsh and marched to Valley Forge. The 13-mile (21 km) journey took them eight days. The following April, General Howe resigned and returned to Britain. He was replaced by General Sir Henry Clinton.

Today, parts of the battle area are preserved in Fort Washington State Park. Fort Hill marks where a temporary fort once stood. Militia Hill was where the Pennsylvania militia held their positions. The Emlen House, where Washington had his headquarters, still stands today.

Images for kids

-

Colonel Daniel Morgan

-

Captain John Montresor helped build defenses around British-occupied Philadelphia.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |