Colonel Tye facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Titus Cornelius

|

|

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1753 Colt's Neck, New Jersey, Great Britain |

| Died | September 1780 (aged c. 27) Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States |

| Allegiance | Great Britain |

| Years of service | 1778-1780 |

| Battles/wars | |

Titus Cornelius, also known as Titus, Tye, and famously as Colonel Tye (c. 1753 – September 1780), was an African American who was born into slavery in New Jersey. He bravely escaped his master and became a skilled leader and fighter for the British during the American Revolutionary War. He was part of a group called the Ethiopian Regiment and later led his own unit, the Black Brigade. Colonel Tye was known for his clever fighting tactics and was one of the most feared leaders opposing the American forces in central New Jersey. He died in September 1780 from an infection after being wounded in a fight.

Contents

Early Life and Escape from Slavery

Titus Cornelius was born into slavery around 1753 in Colt's Neck, Monmouth County, New Jersey. His owner was John Corlies, a Quaker. Titus worked on Corlies' farm near the Navesink River and the town of Shrewsbury.

At the start of the American Revolution, New Jersey had about 8,200 enslaved people. This was the second-highest number among the northern American colonies, after New York. Even though many Quakers were starting to oppose slavery, John Corlies continued to own enslaved people.

Quaker traditions usually meant teaching enslaved people to read and write, and freeing them at age 21. However, Corlies did not educate his enslaved workers and kept them past the age of 21. He was known for treating them very harshly. In late 1775, a group of Quakers from Shrewsbury tried to talk to Corlies about how he treated his enslaved people.

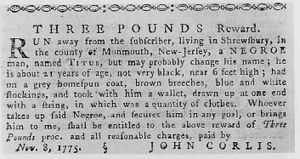

Titus escaped from slavery later that year. His master offered a reward for his capture:

Run away from the subscriber, living in Shrewsbury, in the county of Monmouth, New Jersey, a Negroe man, named Titus, but may probably change his name; he is about 21 years of age, not very black, near 6 feet high; had on a grey homespun coat, brown breeches, blue and white stockings, and took with him a wallet, drawn up at one end with a string, in which was a quantity of clothes. Whoever takes said Negroe, and secures him in any gaol, or brings him to me, shall be entitled to the above reward of Three Pounds, proc. And all reasonable charges paid by John Corlis.

The Quakers were unhappy that Corlies refused to free his enslaved people or educate them. Corlies said he didn't feel it was his duty to free them. Titus learned about the area's families and their political views on his own. In 1778, the Quakers removed Corlies from their group because he refused to free his enslaved people.

Joining the British Forces

In November 1775, Lord Dunmore, the British governor of Virginia, made an important announcement. He offered freedom to all enslaved people and indentured servants who would leave their American masters and join the British side. This offer encouraged many African Americans to escape and join the British. It's estimated that nearly 100,000 enslaved people escaped during the Revolution, with some joining the British. American plantation owners were very angry about Dunmore's offer.

Titus Cornelius escaped from Corlies' farm the day after Dunmore's announcement. He decided to join the British forces. Titus had seen the Quakers try and fail to convince Corlies to free his enslaved people. Turning 21, the age when most Quakers freed their enslaved people, also inspired him to leave. Carrying only a small bag of clothes, Titus headed towards Williamsburg, Virginia. Corlies placed ads in newspapers, offering a reward of "three pounds" for Titus's capture.

Fighting in the American Revolutionary War

Ethiopian Regiment and Black Brigade

After escaping, Titus took the name "Tye" and joined the Ethiopian Regiment. He also became a leader of the "Black Brigade," a fighting group made up of both Black and white Loyalists. This group had a base called "Refugeetown" in Sandy Hook on the Atlantic coast.

Tye first saw action at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778. During this battle, he captured Captain Elisha Shepard of the Monmouth militia. Shepard was then imprisoned in British-held New York City. The Battle of Monmouth, fought near Freehold, New Jersey, didn't have a clear winner. However, it showed both British and American forces how skilled Tye was as a soldier.

Leading the Black Brigade

Colonel Tye knew the area around Monmouth County very well. His bold leadership quickly made him a well-known and feared Loyalist guerrilla commander. The British paid him and his mixed-race group to cause trouble for the American forces in the region. This plan was set up by Royal Governor William Franklin, who was the Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin. It was a way to get back at the Americans for taking over properties belonging to Loyalists.

When American Patriots in Monmouth County started punishing captured Loyalists severely, Franklin and other British officials began raiding American towns. On July 15, 1779, Tye led a daring raid on Shrewsbury, New Jersey. He was joined by a Loyalist named John Moody and 50 African Americans. They captured 80 cattle, 20 horses, and two important local residents, William Brindley and Elisha Cook. The British officers paid Tye and his men five gold guineas for their successful raids. Tye and his fighters often operated from their hidden base in Refugeetown, Sandy Hook. They frequently targeted wealthy Patriots who owned enslaved people, often raiding at night. Tye led many successful raids in the summer of 1779, taking food and fuel, capturing prisoners, and freeing many enslaved people.

By the winter of 1779, Colonel Tye was leading the "Black Brigade," which had 24 Black Loyalists. Tye's group worked with a white Loyalist unit called the "Queen's Rangers" to defend British-occupied New York City. Tye and his men would travel secretly into Monmouth County towns. They would seize cattle, supplies, and silver, bringing these resources back to the British forces. The Black Brigade also helped enslaved people escape to British lines. Later, they helped transport them to Nova Scotia for a new life. They also raided Patriot supporters in New Jersey, capturing them for rewards. Because they had been treated unfairly as enslaved people, the Black Brigade often targeted their former masters and their friends. Patriots feared the Black Brigade more than the regular British army because its members knew the homes of Patriots from their time as enslaved people.

Henry Muhlenberg, a German pastor, wrote about how strong the Black Brigade was. He said that the "regiment of Negroes" were "fitted for and inclined towards barbarities, are lack in human feeling and are familiar with every corner of the country." Reports that African Americans planned attacks on white settlers in Elizabeth and Somerset County increased the local population's fear of Tye and his men.

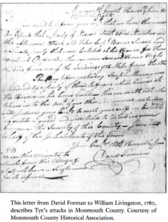

To protect themselves from Tye and other Loyalist raids, the Monmouth County Whigs formed the Association for Retaliation. This group was led by David Forman, a general in the New Jersey militia. Panicked white Patriots asked Governor William Livingston for help. David Forman wrote to Livingston, explaining how widespread Tye's attacks were. Livingston responded by declaring martial law, which is when the military takes control. This made even more African Americans flee to British-held New York. For example, 29 African American men and women left their enslavers in Bergen County during this time. In response, Livingston and his officials encouraged enslavers to move their enslaved people to more remote parts of New Jersey.

On March 30, 1780, the Black Brigade captured Captain James Green and Ensign John Morris. In the same raid, Tye and his men looted and burned the home of John Russell. Russell was killed, and his young son was injured.

Starting in June 1780, Tye led more attacks in Monmouth County. In a notable raid on June 22, 1780, Tye and his men captured James Mott, a major in the Monmouth militia, and James Johnson, a captain in the Hunterdon militia, along with six other militia members. On September 1, 1780, Tye led a small group of African Americans and Queen's Rangers to Colt's Neck, New Jersey. Their goal was to raid the home of Captain Joshua Huddy. Huddy was known for his quick punishment of captured Loyalists, making him an important target for Tye. Tye briefly captured Huddy, but a surprise attack by Patriots helped Huddy escape. Huddy and a female servant had fought off Tye's group for two hours before the Loyalists set fire to the house. Tye was injured in this fight.

Death of Colonel Tye

Colonel Tye developed tetanus and gangrene from the wound he got during the raid against Huddy. He died two days later from the infection.

New Leader of the Black Brigade

After Colonel Tye's death, Colonel Stephen Blucke took command of the Black Loyalist unit, the Black Company of Pioneers. Blucke successfully led Tye's troops for the rest of the war, even continuing operations after the British surrendered at Yorktown. After Huddy's death on April 12, 1782, the "Black Brigade" broke up, and most of its members sought safety in Canada.

Legacy of Colonel Tye

Colonel Tye is often seen as one of the most effective and respected African American soldiers of the Revolution. He made important contributions to the British cause. Even though the British Army never officially made him an officer, "Colonel Tye" was an honorary title. It showed respect for his amazing tactical and leadership skills. The British often gave such titles to other important Black officers in Jamaica and other West Indian islands. The British army did not formally appoint anyone of African descent to such positions, but the Royal Navy did.

Tye's knowledge of the swamps, rivers, and inlets in Monmouth County was very important for the British efforts in New Jersey during the war. As the commander of the Black Brigade, he led many raids against American Patriots.

Tye played a crucial role for the British forces in the area, leading many successful raids and battles against the local Patriots. He also did a great deed by freeing enslaved people and enlisting some to fight alongside him. Historian Robert Mayers wrote about Tye, saying, "Tye's reputation lived on among his comrades, as well as among his enemies. Many Americans contended that the war at the New Jersey shore would have been won much sooner had Tye been enlisted on their side. Others observed that had he lived on for the rest of the war, it would have been a disaster for the Patriots of Monmouth County. Ironically, Tye and other African-American Loyalists fought against the Patriots not because of their loyalty to the Crown but for many of the same freedoms the Patriots had demanded from the King."

Colonel Tye's story shows the important role African Americans played during the Revolutionary War. Dunmore's Proclamation involved the African American population in the war in a new way. The promise of freedom inspired African American men like Tye to join the Loyalist side. Tye and his men captured important Patriot militia members, launched many raids, and took valuable resources from the local population. Their actions caught the attention of Governor William Livingston, who declared martial law in New Jersey to try and restore order. The actions of Tye and other formerly enslaved people made white settlers fear that the war would cause more chaos and disorder. Tye's actions also increased white anxieties about slave revolts and strengthened feelings against ending slavery.

See also

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |