Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Southern theater |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

The Battle of Cowpens |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

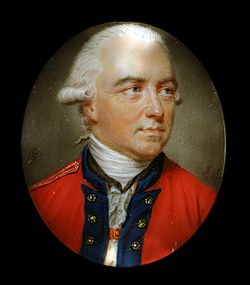

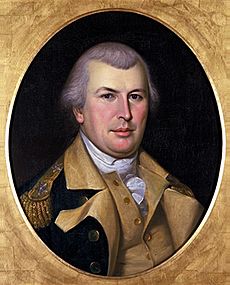

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Southern Army Main Army Rochembeau's Expeditionary Force Gálvez Force |

British Southern Army, Totalling approximately 8,000 regulars and militia | ||||||

The Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War was a major part of the American Revolutionary War. It included battles and fighting mainly in Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. This part of the war lasted from 1778 to 1781. Both large battles and smaller guerrilla warfare tactics were used.

For the first three years of the war (1775–1778), most big battles happened in the northern colonies. These were around cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. After a big British loss at Saratoga, the British changed their plan. They decided to focus on the southern colonies. They hoped to win the war by taking control of the South. Before 1778, American Patriots mostly controlled these southern areas. They had their own governments and local fighters called militias. The Continental Army also helped defend Charleston in 1776. They also fought against British supporters called Loyalists.

The British started their "Southern Strategy" in late 1778 in Georgia. They had early success by capturing Savannah. Then, in 1780, they won big victories in South Carolina. They defeated American forces at Charleston and Camden. At the same time, France (in 1778) and Spain (in 1779) joined the war. They fought against Great Britain to help the United States. Spain took over all of British West Florida, ending with the siege of Pensacola in 1781. France first sent only naval support. But in 1781, they sent many soldiers to join General George Washington's army. They marched from New York to Virginia.

General Nathanael Greene took over the Continental Army in the South after the loss at Camden. He used a strategy of avoiding big battles and wearing down the British. The two armies fought many battles. Most were tactical wins for the British, but they lost many soldiers. This weakened them, while the American army stayed strong. The Battle of Guilford Court House is a good example of this. American victories like the Battle of Cowpens and the Battle of Kings Mountain also hurt the British. The final big battle was the Siege of Yorktown. British General Lord Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781. This was the last major battle of the war. Soon after, peace talks began. These led to the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Early Battles: 1775–1778

Virginia's Fight for Freedom

In most colonies, British officials left quickly as Patriots took control. But in Virginia, the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, resisted. On April 20, 1775, he moved gunpowder from Williamsburg. He took it to a British warship. Dunmore wanted to stop Virginia's local fighters from getting supplies. Patriot militia, led by Patrick Henry, made Dunmore pay for the gunpowder. Dunmore kept looking for military supplies. Patriots often moved supplies before he arrived.

In November 1775, Dunmore offered freedom to enslaved people who fought for the British. His troops fought Patriot militiamen at Kemp's Landing. Then, on December 9, Patriots defeated Loyalist troops at the Battle of Great Bridge. These Loyalist troops included formerly enslaved people in Dunmore's "Ethiopian Regiment." Dunmore and his troops went to British ships near Norfolk. On January 1, 1776, these ships attacked and burned Norfolk. Patriots in the town finished destroying the former Loyalist stronghold. Dunmore was forced out of Virginia that summer. He never returned.

Georgia's Early Struggles

Georgia's royal governor, James Wright, stayed in power until January 1776. Then, British ships arrived near Savannah. The local Committee of Safety ordered his arrest. Patriots and Loyalists thought the ships were there to help the governor. But the fleet was actually sent from Boston to get rice. Wright escaped and reached the fleet. In the Battle of the Rice Boats in March, the British successfully left Savannah. They took many merchant ships full of rice.

The Carolinas Divided

South Carolina was divided when the war started. People in the lowlands, especially around Charleston, supported the Patriots. But many in the back country were Loyalists. By August 1775, both sides were forming their own fighting groups. In September, Patriots took Fort Johnson, Charleston's main defense. Governor William Campbell fled to a British ship.

Loyalists seized gunpowder meant for the Cherokee. This made tensions worse. It led to the first siege of Ninety Six in November. Patriots were getting more fighters than Loyalists. A big campaign called the Snow Campaign (because of heavy snow) involved 5,000 Patriots. Led by Colonel Richard Richardson, they captured or drove away most Loyalist leaders. Loyalists fled to East Florida or Cherokee lands. Some Cherokee, called the Chickamauga, supported the British in 1776. They were defeated by fighters from North and South Carolina.

To control the South, the British needed a port for supplies and soldiers. They planned an expedition to set up a strong base. They also sent leaders to recruit Loyalists in North Carolina. But the expedition from Europe was very late. The Loyalist force that was supposed to meet them was badly defeated. This happened at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge in February 1776. When General Henry Clinton arrived in North Carolina in May, he found it unsuitable. The Royal Navy found Charleston, South Carolina, to be a better spot. Its defenses were not finished and seemed weak. In June 1776, Clinton and Admiral Sir Peter Parker attacked Fort Sullivan. This fort guarded Charleston harbor.

Clinton had not fully checked the area. His 2,200 men landed on Long Island, next to Sullivan's Island. But the water between the islands was too deep to cross. Instead of moving his troops by boat, he relied on the navy to destroy the fort. The fort later became known as Fort Moultrie. However, the British ships' cannons could not damage the fort's defenses. These were made of spongy palmetto logs. The attack failed. It was a humiliating loss. Clinton called off his campaign in the Carolinas. Clinton and Parker blamed each other for the failure. Some believe this failure to take Charleston in 1776 was a major mistake. It left Loyalists without support for three years. It also allowed Charleston to help the American cause until 1780.

British East Florida Remains Strong

Patriots in Georgia tried several times to defeat the British. The British had a base at Saint Augustine in British East Florida. This base supported Loyalists who fled there from other southern states. These Loyalists raided farms in southern Georgia for cattle and supplies. The first attempt to attack was led by Charles Lee. But it stopped when he was called back to the main army. The second attempt was in 1777. Georgia Governor Button Gwinnett organized it. It also failed. Gwinnett and his militia leader, Lachlan McIntosh, disagreed on everything. Some Georgia militia made it into East Florida. But they were stopped at the Battle of Thomas Creek in May.

The last expedition was in early 1778. More than 2,000 American soldiers and state militia were gathered. But it also failed. This was due to disagreements between General Robert Howe and Georgia Governor John Houstoun. A small fight at Alligator Bridge in June happened. But tropical diseases and leadership problems hurt the Patriot forces. East Florida remained firmly in British hands for the rest of the war.

British Southern Campaign Begins

The Loyalist Question

In 1778, the British focused on the South again. They hoped to regain control by getting thousands of Loyalists to join them. They believed many Loyalists would help. This belief came from Loyalist exiles in London. These exiles had direct access to British leaders. They wanted their lands back and rewards for their loyalty. So, they exaggerated how much Loyalist support there would be. They had a lot of influence on British officials. Also, some Loyalists had strong business and family ties in London. The British expected a lot of support if they freed certain areas.

However, this idea was mostly wrong. Cornwallis realized this as the campaign went on. He wrote to Clinton that "Our assurances of attachment from our poor distressed friends in North Carolina are as strong as ever." But not enough Loyalists joined. Those who did were often in danger once the British army moved on.

British Capture Savannah

On December 29, 1778, a British force of 3,500 men from New York arrived. Led by Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell, they captured Savannah, Georgia. In mid-January 1779, Brigadier General Augustine Prevost joined them. He brought troops who had marched from Saint Augustine. Prevost took command of the forces in Georgia. He sent Campbell with 1,000 men toward Augusta. Their goals were to control Augusta and recruit Loyalists.

The American defenders of Savannah had retreated. They went to Purrysburg, South Carolina, about 12 miles (19 km) from Savannah. There, they met Major General Benjamin Lincoln. He was the commander of Continental Army forces in the South. Lincoln marched most of his army from Charleston, South Carolina. He wanted to watch and oppose Prevost. In early February 1779, Prevost sent a few hundred men to Beaufort. This was likely to distract Lincoln from Campbell's movements. Lincoln sent General Moultrie and 300 men to drive them out. The Battle of Beaufort was not a clear win for either side. Both groups eventually went back to their bases.

Meanwhile, Campbell had taken control of Augusta easily. Loyalists began to join him. He signed up over 1,000 men in two weeks. But he could not stop a large group of Loyalists from being defeated. Patriot militia, led by Andrew Pickens, won the Battle of Kettle Creek on February 14, 1779. This battle was 50 miles (80 km) from Augusta. It showed everyone that the British army could not always protect Loyalists. Campbell suddenly left Augusta. This was likely because John Ashe arrived with over 1,000 North Carolina militia. Lincoln had sent them to join the 1,000 militia already across the river in South Carolina. On the way back to Savannah, Campbell gave command to Augustine Prevost's brother, Mark. Mark Prevost surprised Ashe, who was following him south. He almost destroyed Ashe's force of 1,300 men in the Battle of Brier Creek on March 3.

Second Attack on Charleston

By April, Lincoln had more South Carolina militia. He also received military supplies through Dutch shipments to Charleston. He decided to move toward Augusta. He left 1,000 men under General Moultrie at Purrysburg. Their job was to watch Augustine Prevost. Lincoln began his march north on April 23, 1779. Prevost reacted by leading 2,500 men from Savannah toward Purrysburg on April 29. Moultrie fell back toward Charleston instead of fighting. Prevost was within 10 miles (16 km) of Charleston by May 10. Then he started to face resistance. Two days later, he learned that Lincoln was rushing back from Augusta. Prevost retreated to islands southwest of Charleston. He left a fortified guard at Stono Ferry to cover his retreat. When Lincoln returned to Charleston, he led about 1,200 men after Prevost. This force was pushed back by the British on June 20, 1779, at the Battle of Stono Ferry. The British rear guard left that post a few days later. Prevost's attack on Charleston was known for his troops' looting. This angered everyone in the South Carolina low country.

Defending Savannah

In October 1779, French and American forces tried to retake Savannah. General Lincoln led the Americans. A French naval squadron, led by Comte d'Estaing, helped. But it was a huge failure. The combined French-American forces lost about 901 men. The British lost only 54. The French Navy found Savannah's defenses strong. They were like those that stopped Admiral Peter Parker at Charleston in 1776. The cannon fire had little effect on the defenses. Unlike Charleston, where Clinton decided not to attack Fort Moultrie by land, Estaing decided to attack after the naval bombardment failed. In this attack, Count Kazimierz Pułaski, a Polish cavalry commander, was badly wounded. With Savannah safe, Clinton could launch a new attack on Charleston. Lincoln moved his remaining troops to Charleston to help build its defenses.

Third Attack on Charleston

Clinton attacked Charleston in 1780. He blocked the harbor in March. He built up about 10,000 troops in the area. His advance on the city was unopposed. The American naval commander, Commodore Abraham Whipple, sank five of his eight frigates. This created a barrier for defense. Inside the city, General Lincoln had about 2,650 American soldiers and 2,500 militiamen. British colonel Banastre Tarleton cut off the city's supply lines. He won battles at Moncks Corner in April and Lenud's Ferry in early May. Charleston was surrounded. Clinton began building siege lines. On March 11, he started firing cannons at the town.

On May 12, 1780, General Lincoln surrendered his 5,000 men. This was the largest surrender of U.S. troops until the American Civil War. With few losses, Clinton had taken the South's biggest city and port. This was perhaps the greatest British victory of the war. This win left the American military in the South in ruins. It was only after Nathanael Greene outmaneuvered Cornwallis in 1781 that the British lost this advantage.

The remaining American army in the South began to retreat. They headed toward North Carolina. But Colonel Tarleton chased them. He defeated them at the Battle of Waxhaws on May 29. After the battle, stories spread that Tarleton's forces had killed many Patriots after they surrendered. Because of this, "Bloody Tarleton" became a hated name. The phrase "Tarleton's quarter" meant no mercy. It became a rallying cry for the Patriots. Whether or not it was a massacre, the battle had a big impact. When Loyalist militia surrendered at the end of the Battle of Kings Mountain, many were killed. Patriot sharpshooters kept firing, shouting "Tarleton's Quarters!" Tarleton later wrote about the war. He did not mention accusations of bad conduct. He presented himself in a positive way.

Cornwallis Takes Charge

After Charleston, organized American military action in the South almost stopped. The states kept their governments running. The war was carried on by local fighters called partisans. These included Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, William R. Davie, Andrew Pickens, and Elijah Clarke. General Clinton gave control of British operations in the South to Lord Cornwallis. The Continental Congress sent General Horatio Gates, who had won at Saratoga, to the South with a new army. But Gates quickly suffered a terrible defeat at the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780. Cornwallis then prepared to invade North Carolina.

Cornwallis tried to get many Loyalists to join him in North Carolina. But Patriot militia crushed a larger force of Loyalists. This happened at the Battle of Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780. Many Patriot men had crossed the Appalachian Mountains from the Washington District to fight the British. They were called the Overmountain Men. The British plan to raise large Loyalist armies failed. Not enough Loyalists joined. Those who did were at high risk once the British army moved on. The defeat at Kings Mountain and constant attacks on his supply lines by militia forced Cornwallis to retreat. He spent the winter in South Carolina.

Gates was replaced by General Nathanael Greene. Greene was Washington's most trusted officer. Greene gave about 1,000 men to General Daniel Morgan. Morgan was an excellent tactician. He crushed Tarleton's troops at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781. As after Kings Mountain, Cornwallis was criticized for splitting his army without enough support. Greene then wore down his opponents. He used a series of small fights and movements called the "Race to the Dan." Each fight was a tactical win for the British. But they gained no strategic advantage. They lost many soldiers. The American army remained strong.

Cornwallis knew Greene had divided his forces. He wanted to fight either Morgan's or Greene's group before they could rejoin. He removed all extra baggage from his army. He wanted to keep up with the fast-moving Patriots. When Greene heard this, he was happy. He said, "Then, he is ours!" Cornwallis's lack of supplies later caused him problems.

Greene first fought Cornwallis at the Battle of Cowan's Ford. Greene had sent General William Lee Davidson with 900 men. When Davidson was killed, the Americans retreated. Greene was weaker, but he continued his delaying tactics. He fought many more small battles in South and North Carolina. About 2,000 British troops died in these fights. Greene summed up his strategy with a famous motto: "We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again." His tactics were like the Fabian strategy used by the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus. Fabius wore down the stronger forces of Hannibal through a slow war of attrition. Greene eventually felt strong enough to face Cornwallis directly. This was near New Garden, North Carolina (now Greensboro, North Carolina). Cornwallis won the Battle of Guilford Court House tactically. But his army suffered so many losses. He had to retreat to Wilmington, North Carolina, for supplies and reinforcements.

Cornwallis could not completely destroy Greene's army. He realized that American supplies came from Virginia. Virginia had been mostly untouched by the war. Against Clinton's wishes, Cornwallis decided to invade Virginia. He hoped that cutting off supplies to the Carolinas would stop American resistance there. This idea was supported by Lord George Germain. Germain sent letters that left Clinton out of decisions for the Southern Army. Clinton was supposed to be the overall commander. Without telling Clinton, Cornwallis marched north into Virginia. He engaged in raids there. He met the army commanded by William Phillips and Benedict Arnold. These raids destroyed many tobacco fields and barns. Colonists used tobacco to fund their war efforts. The British destroyed about 10 million pounds of tobacco in 1780 and 1781. This became known as the Tobacco War.

When Cornwallis left Greensboro for Wilmington, Greene could begin retaking South Carolina. He achieved this by the end of June. This was despite a loss to Lord Rawdon at Hobkirk's Hill on April 25. From May 22 to June 19, 1781, Greene led the siege of Ninety-Six. He had to stop the siege when he heard Rawdon was bringing troops to help. However, Greene and militia leaders like Francis Marion forced Rawdon to leave the Ninety Six District and Camden. This left the British with only the port of Charleston in South Carolina. Augusta, Georgia, was also besieged on May 22. It fell to Patriot forces under Andrew Pickens and Harry "Light Horse" Lee on June 6. This reduced the British presence in Georgia to only the port of Savannah.

Greene then let his forces rest for six weeks. This was on the High Hills of the Santee River. On September 8, with 2,600 men, he fought British forces. These were led by Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Stewart at Eutaw Springs. Americans who died in this battle were remembered by author Philip Freneau. He wrote a poem in 1781 called "To the Memory of Brave Americans." The battle was a draw. But it weakened the British so much that they retreated to Charleston. Greene kept them trapped there for the rest of the war.

Yorktown: The Final Battle

When Cornwallis arrived in Virginia, he took command of the British forces there. These forces had been led by Benedict Arnold, and then by Major General William Phillips. Phillips, a friend of Cornwallis, died two days before Cornwallis reached Petersburg. Cornwallis had marched north without telling Clinton. Communication between the two British commanders was by sea and very slow. It could take up to three weeks. Cornwallis sent word of his march north. He then began destroying American supplies in the Chesapeake region.

In March 1781, General Washington sent the Marquis de Lafayette to defend Virginia. This was in response to the threat from Arnold and Phillips. Lafayette had 3,200 men. But British troops in the state totaled 7,200. Lafayette had small fights with Cornwallis. He avoided a big battle while gathering more soldiers. During this time, Cornwallis received orders from Clinton. He was told to choose a spot on the Virginia Peninsula and build a fortified naval post. This post would protect large warships. By following this order, Cornwallis put himself at risk of being trapped.

The French fleet, led by the Comte de Grasse, arrived. General Washington's combined French-American army also arrived. Cornwallis found himself cut off. The British Royal Navy fleet, under Admiral Thomas Graves, was defeated by the French. This happened at the Battle of the Chesapeake. Then, French siege cannons arrived from Newport, Rhode Island. Cornwallis's position became impossible to hold. Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington and the French commander, the Comte de Rochambeau. This happened on October 19, 1781.

Cornwallis reported this disaster to Clinton in a letter. It began: "I have the mortification to inform Your Excellency that I have been forced to give up the posts of York and Gloucester and to surrender the troops under my command by capitulation, on the 19th instant, as prisoners of war to the combined forces of America."

What Happened Next

With the surrender at Yorktown, the British war effort largely stopped. French forces played a big part in that battle. Cornwallis's army was lost. The only remaining large British army in America was under Sir Henry Clinton in New York. Clinton was shocked by the defeat. He took no further action. Guy Carleton replaced him in 1782. This shocking loss, coming after a rare naval defeat, made more British people turn against the war. The government led by Lord North collapsed. A new government that wanted peace took power. No more major battles happened on the American continent for the rest of the war. Saratoga had started the decline of British fortunes. But Yorktown was the final blow to their hopes of winning the Revolution.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |