Burning of Norfolk facts for kids

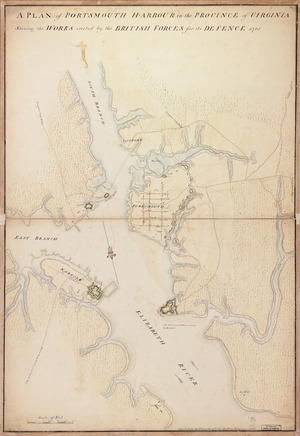

Detail from a 1775 map showing the Norfolk area. Oriented with North to the bottom, Great Bridge is visible near the top of the map, and Norfolk is center-right.

|

|

| Date | January 1, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Location | Norfolk, Virginia |

| Participants | |

| Outcome | Destruction of the town by combined action of British and Whig forces |

The Burning of Norfolk happened on January 1, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. British ships in the harbor of Norfolk, Virginia, started firing cannons at the town. Then, landing parties came ashore to burn certain buildings. The town's people, many of whom supported the British, had already left. Patriot (also called Whig) forces from Virginia and North Carolina were occupying the town.

Even though these Patriot forces tried to stop the British landing parties, they did not try to stop the fires. In fact, they started burning and looting buildings that belonged to people who supported the British. After three days, most of the town was destroyed, mainly by the Patriot forces. They finished destroying the town in early February to make sure the British couldn't use any part of it. Norfolk was the last important place where the British had power in Virginia. After raiding Virginia's coast for a while, the last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, left for good in August 1776.

Contents

Why Did the Burning of Norfolk Happen?

Tensions grew in the British Colony of Virginia in April 1775. This was around the same time the American Revolutionary War began in Province of Massachusetts Bay with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Rebellious Patriots, who controlled the local assembly, started gathering troops in March 1775. This led to a fight over who controlled the colony's military supplies.

Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, ordered British marines to remove gunpowder from the colonial storehouse in Williamsburg. This worried the colonial lawmakers and caused a militia uprising. The problem was solved without fighting. But Dunmore feared for his safety and left Williamsburg in June 1775. He put his family on a British ship.

A small British fleet then gathered at Norfolk. This port town had many merchants who supported the British. Even though some Patriots lived there, the threat from the British fleet likely kept them quiet.

Growing Conflict in Virginia

Small fights continued in Virginia between Patriots and British supporters. In October, Dunmore had enough military help to start organized actions against the Patriots. General Thomas Gage, the British commander in North America, sent a small group of soldiers to Virginia. These troops began raiding nearby areas for Patriot military supplies on October 12.

This continued until the end of October. A small British ship got stuck and was captured by Patriots near Hampton. British navy boats sent to punish the town were pushed back by Continental Army troops and militia. This brief gunfight resulted in some sailors being killed or captured.

Dunmore reacted by issuing a proclamation on November 7. He declared martial law, meaning the military would be in charge. He also offered freedom to enslaved people owned by Patriots if they would fight for the British Army. This idea worried both British supporters and Patriots who owned enslaved people. They were concerned about armed former enslaved people and losing their property.

Despite this, Dunmore was able to recruit enough enslaved people to form the Ethiopian Regiment. He also raised a company of British supporters called the Queen's Own Loyal Virginia Regiment. These local forces joined the two companies of British soldiers already in the colony. Dunmore was hopeful, writing on November 30, 1775, that he would soon be able to make the colony "do their duty."

The Battle of Great Bridge

Virginia's assembly had sent militia companies to Hampton under William Woodford, a colonel in the 2nd Virginia Regiment. More militia kept arriving in Williamsburg. Woodford's force grew to 700 men and moved toward Great Bridge in early December.

Some of Dunmore's troops had built defenses on the north side of the bridge. So, Woodford began building his own defenses on his side. More and more militia companies arrived from nearby counties and North Carolina. On December 9, British troops tried to scatter Woodford's force. But they were strongly defeated.

After the battle, the British retreated back into Norfolk. Soon after, Dunmore and all his forces went onto British ships in Norfolk's harbor. Most of the remaining British supporters in the town also left. Woodford's force continued to grow when Colonel Robert Howe and North Carolina soldiers arrived the day after the battle.

Patriot Forces Take Over Norfolk

On December 14, the Patriot forces had grown to about 1,200 men. Howe and Woodford moved into Norfolk. Since Colonel Howe was a higher-ranking officer in the Continental Army, he took command of the forces in the town. He was very strict in his dealings with Dunmore and the British navy captains. He refused to let supplies be delivered to the crowded British ships. He also insisted on fair exchanges of prisoners.

Howe and Woodford were worried about a possible British attack. At first, they asked for more troops. But after thinking about it, they realized the British fleet could easily sail around the town and trap their soldiers. So, they told the Virginia assembly that the town should be abandoned and made useless to the enemy.

On December 20, the Liverpool arrived with a supply ship. Dunmore placed four ships—the Dunmore, the Liverpool, the Otter, and the Kingfisher—in a threatening line along the town's waterfront. This caused many people and their belongings to leave the town. On Christmas Eve, Captain Henry Bellew of the Liverpool sent a message to the town. He said he preferred to buy supplies instead of taking them by force. Howe refused this offer and got ready for a bombardment.

On December 30, Bellew demanded that the Patriot forces stop parading and changing the guard on the waterfront. He found it offensive. He also suggested it would be smart for women and children to leave the town. Howe refused to move his men. He told Bellew, "I am too much an Officer [...] to recede from any point which I conceive to be my duty."

The Burning and Looting of Norfolk

On New Year's Day 1776, Howe's guards paraded as usual. Between 3:00 and 4:00 pm, the four British ships started firing their cannons at the town. With more than 100 guns, they shelled the town late into the evening. Landing parties were sent ashore. Some went to get supplies, others to set fire to buildings that Patriot snipers had used to shoot at the ships. The British actions were not perfectly planned, but they managed to set most of the waterfront on fire.

The Patriot militia fought the landing parties. However, they did little to stop the flames, which spread quickly because of strong winds. Some buildings belonging to British supporters were burned and looted by the Patriots soon after the shelling began. This included a local distillery. Even though the British stopped their actions that day, the fires continued to burn. The next morning, Colonel Howe reported that "the whole town will I doubt not be consum'd in a day or two." The burning and looting by the occupying Patriots continued for three days. By the time order was restored, much of the town was destroyed.

What Happened After the Fire?

The damage done to the town by the Patriot forces was much greater than what the British did. The Patriots destroyed 863 buildings, valued at about £120,000. In comparison, the British shelling destroyed only 19 buildings, worth £3,000. This was in addition to £2,000 in damages caused by Lord Dunmore during the British occupation.

Colonel Howe's report to the Virginia Convention did not mention the role of the Patriot forces in the burning. He repeated the idea that the town should be completely destroyed. A newspaper story published by Lord Rawdon raised some questions among Patriots about the event. But many people thought the British were responsible for most of the damage. No investigations were done right away.

The convention approved Howe's plan. By February 6, the remaining 416 buildings had been destroyed. It wasn't until 1777 that the full extent of Patriot involvement in the burning was admitted.

Patriot forces left the ruined town after finishing its destruction. They moved to other nearby towns. They were further organized in March when General Charles Lee arrived to take command of the Continental Army's Southern Department. He gathered the militia to force Dunmore out of a camp he had set up near Portsmouth. Dunmore finally left Virginia for good in August 1776.

Before the war, Fort Nelson and the area that would become Fort Norfolk had some defenses. However, these defenses were too weak to stop the British Royal Navy from attacking Norfolk. Because of this, after the war, the U.S. government bought the fortified land in Norfolk and built Fort Norfolk. Both forts were made stronger and used to prevent any more naval attacks on the cities along the Elizabeth River.

There is a marker at St. Paul's Boulevard and City Hall Avenue in Norfolk that remembers this event.

Images for kids

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |