Chickamauga Cherokee facts for kids

The Chickamauga Cherokee were a group of Cherokee people. They chose to separate from the main Cherokee Nation during the American Revolutionary War. Most Cherokee wanted peace with the Americans by late 1776. This was after some tough battles and American attacks.

A leader named Dragging Canoe (also called a red chief) led his followers away. In the winter of 1776–77, they moved down the Tennessee River. They left their old Overhill Cherokee towns. They built 11 new towns in a more hidden area. This helped them stay away from American settlers.

American settlers linked Dragging Canoe and his group to their new town on Chickamauga Creek. They started calling them the Chickamaugas. Five years later, the Chickamauga moved further west and southwest. They settled in what is now Alabama. There, they built five larger towns. People then called them the Lower Cherokee. This name was used for the people of these "Five Lower Towns".

Contents

Moving to New Homes

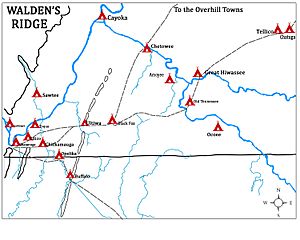

The First "Chickamauga" Towns

In the winter of 1776–77, Dragging Canoe and his Cherokee followers moved. They had supported the British when the American Revolutionary War began. They traveled down the Tennessee River. They left their historic Overhill Cherokee towns. They built about a dozen new towns in this frontier area. They hoped to get away from the growing number of European-American settlers.

Dragging Canoe and his people settled where the Great Indian Warpath crossed Chickamauga Creek. This was near what is now Chattanooga, Tennessee. They named their town Chickamauga after the creek. The whole area around it was called the Chickamauga area. American settlers used this name to describe the fighting Cherokee in this region as "Chickamaugas."

In 1782, militia forces led by John Sevier and William Campbell destroyed these eleven Cherokee towns. Dragging Canoe then led his people further down the Tennessee River. They built five new towns, which became known as the Lower Cherokee towns.

After the Revolutionary War, more pioneers moved west. These settlers came from the new states of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

The "Five Lower Towns"

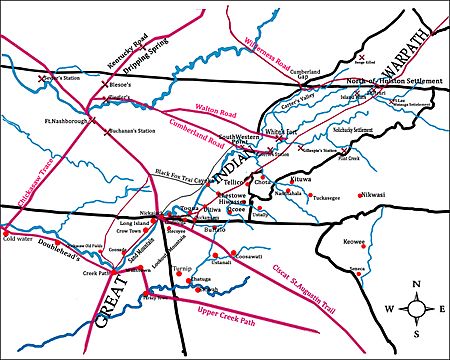

Dragging Canoe moved his people west and southwest. They settled in new areas in Georgia. Their main town was Running Water on Running Water Creek. Other towns built at this time included Nickajack, Long Island, Crow Town, and Lookout Mountain Town. Over time, more towns grew to the south and west. All these settlements were called the Lower Towns.

Years of Fighting

The Chickamauga Cherokee became known for their strong dislike of United States settlers. These settlers had pushed them out of their traditional lands. From Running Water town, Dragging Canoe led attacks on white settlements. These attacks happened all over the Southeastern United States.

The Chickamauga/Lower Cherokee and the frontier settlers fought constantly until 1794. Chickamauga warriors raided as far as Indiana, Kentucky, and Virginia. They also worked with members of the Northwestern Confederacy. Many Cherokee eventually joined the fight against the United States. This was due to growing belief in the Chickamauga cause. It was also because the U.S. destroyed homes of other Native Americans.

Dragging Canoe died in 1792. His chosen successor, John Watts, took charge of the Lower Cherokee. Under Watts, the Cherokee continued their policy of Indian unity. They remained hostile toward European Americans. Watts moved his base to Willstown. This was to be closer to his Muscogee allies. Before this, he made a treaty in Pensacola with the Spanish governor of West Florida, Arturo O'Neill de Tyrone. This treaty provided arms and supplies for the war.

Cherokee Connections

The Chickamauga Towns and later Lower Towns were like other groups of Cherokee settlements. These included the Middle Towns, Out Towns, Valley Towns, and Overhill Towns. These groups were already set up on both sides of the Appalachian Mountains when Europeans first arrived. These groupings were not separate countries. They mostly showed where people lived geographically. People from the Overhill and Valley towns spoke a similar language.

The Cherokee people were very spread out in their government. Their governments were based in the clan and larger town. Townhouses were built for community meetings. Some towns were linked to smaller villages nearby. Even though there were regional councils, they did not have strong power.

Over time, different groups of towns developed different ideas. These ideas were about how to deal with European-Americans. This was partly based on how much they interacted and married with them. This happened through trading and other partnerships.

Before 1788, the only "national" role among Cherokee people was First Beloved Man. This person was a chief negotiator from the towns most isolated from European settlers. After 1788, the people created a national council. But it met rarely and had little power. Even after the peace of 1794, the Cherokee had five groups: the Upper Towns, the Overhill Towns, the Hill Towns, the Valley Towns, and the (new) Lower Towns. Each had its own regional ruling councils. These were seen as more important than the "national" council at Ustanali in Georgia.

Dragging Canoe had spoken to the National Council at Ustanali. He publicly recognized Little Turkey as the main leader of all the Cherokee. The council honored him after his death in 1792. Leaders of the "Chickamauga" often talked with Cherokee from other areas. Warriors from the Overhill Towns supported them in fighting the colonists and later pioneers. Many Chickamauga leaders signed treaties with the U.S. government. They signed along with other leaders of the Cherokee Nation.

After the Wars

After the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in late 1794, leaders from the Lower Cherokee became very important. They led the national affairs of the people. When the national government of all the Cherokee Nation was formed, the first three Principal Chiefs were: Little Turkey (1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller (1811–1827). All these men had fought as warriors under Dragging Canoe. Doublehead and Turtle-at-Home, the first two Speakers of the Cherokee National Council, had also served with Dragging Canoe.

Former warriors from the Lower Towns continued to lead the Cherokee Nation. This lasted well into the 1800s. Even after younger chiefs from the Upper Towns became powerful, the Lower Towns' representatives were still a major voice. The "young chiefs" of the Upper Towns had also fought with Dragging Canoe and Watts.

Settling Down Again

Many former warriors went back to the original Chickamauga area settlements. Some of these places were already reoccupied. They also built new towns in the area, plus some in north Georgia. Others moved into towns built after the earlier move.

In 1799, Brother Steiner, a Moravian Brethren representative, met Richard Fields (Lower Cherokee). Fields had been a warrior. Steiner hired him as a guide and interpreter. The missionary was looking for a good place for a mission and school in the Nation. It was finally built at Spring Place. The land was given by James Vann, who supported European-American education for his people. Once, Steiner asked Fields, "What kind of people are the Chickamauga?" Fields laughed and said, "They are Cherokee, and we know no difference." Neither the Chickamauga nor other Cherokee saw themselves as separate from the larger Cherokee people of that time.

Other Cherokee joined the remaining people from the old Overhill towns. These were on the Little Tennessee River and were called the Upper Towns. Their main center was Ustanali in Georgia. Vann and his friends The Ridge and Charles R. Hicks became their top leaders. These town leaders were the most open to change among the Cherokee. They liked adopting European-American education and modern farming methods.

For about ten years after the fighting ended, the northern Upper Towns had their own council. They recognized the main leader of the Overhill Towns as their chief. They slowly had to move south because they gave their land to the United States.

John McDonald returned to his old home on the Chickamauga River. It was across from Old Chickamauga Town. He lived there until he sold it in 1816. The Boston-based American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions bought it. They used it for the Brainerd Mission. This mission was both a church and a school. It offered academic and job training. His daughter, Mollie McDonald, and son-in-law, Daniel Ross, started a farm and trading post. This was near the old village of Chatanuga. Their son John Ross, born at Turkey Town, later became a principal chief. He guided the Cherokee through the Indian Removals of the 1830s. This was when they were forced to move to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Most of the Lower Cherokee stayed in the towns they lived in by 1794. These were known as the Lower Towns, with their main center at Willstown. The former warriors of the Lower Towns led the political affairs of the Nation for the next twenty years. They were more traditional than the Upper Towns' leaders. They adopted some new ways but tried to keep as many old ways as possible.

Generally, the Lower Towns were south and southwest of the Hiwassee River. They stretched along the Tennessee River down to the northern border of the Muscogee nation. They were west of the Conasauga and Ustanali in Georgia. The Upper Towns were north and east of the Hiwassee. They were between the Chattahoochee River and the Conasauga. This area was similar to the later Amohee, Chickamauga, and Chattooga districts of the Cherokee Nation East.

Also traditional were the Cherokee settlements in the mountains of western North Carolina. These were known as the Hill Towns, with their main center at Quallatown. Similarly, the lowland Valley Towns, with their main center at Tuskquitee, were more traditional. The Upper Town of Etowah was also traditional. It was special because most of its people were full-bloods. Many Cherokee in other towns were of mixed race but identified as Cherokee. Etowah was also the largest town in the Cherokee Nation. The Overhill towns remaining along the Little Tennessee River stayed mostly independent. They kept their main center at Chota.

All five regions had their own councils. These were more important to their people than the national council. This changed after the national council meeting in 1810 at Willstown.

Peacetime Leaders of the Lower Towns

John Watts remained the head of the Lower Cherokee council at Willstown until he died in 1802. After him, Doublehead, who was already a leader, took that position. He held it until his death in 1807. He was killed by The Ridge, Alexander Saunders, and John Rogers. Rogers was a white former trader who first came west with Dragging Canoe in 1777. By 1802, he was considered a member of the Nation and allowed to be on the council. The Glass succeeded him on the council. The Glass was also assistant principal chief of the Nation to Black Fox. The Glass led the Lower Towns' council until the unified council of 1810.

By the time John Norton visited the area in 1809–1810, many former militant Cherokee of the Lower Towns had adopted many American ways. For example, James Vann became a major planter. He owned over 100 African-American slaves. He was one of the wealthiest men east of the Mississippi River. Norton became a personal friend of Turtle-at-Home, John Walker, Jr., and The Glass. All of them were involved in business and trade. When Norton visited, Turtle-at-Home owned a ferry. It had a landing on the Federal Road between Nashville, Tennessee and Athens, Georgia. He lived at Nickajack. This community had grown down the Tennessee River and across it to the north, becoming more important than Running Water.

Georgia and the U.S. government pushed the Cherokee Nation to give up its lands. They wanted them to move west of the Mississippi River. Leaders of the Lower Towns like Tahlonteeskee, Degadoga, John Jolly, Richard Fields, John Brown, Bob McLemore, John Rogers, Young Dragging Canoe, George Guess (Tsiskwaya, or Sequoyah) and Tatsi (Captain Dutch) were among the first to leave. They believed moving was unavoidable because of settlers' greed. They wanted to get the best lands and settlements possible. They moved with their followers to Arkansas Territory. This group later became known as the Cherokee Nation West. They then moved to Indian Territory after a treaty in 1828. They were called the "Old Settlers" in Indian Territory. They lived there for almost ten years before the rest of the Cherokee were forced to join them.

The remaining leaders of the Lower Towns were the strongest supporters of moving west voluntarily. They were strongly opposed by former warriors and their sons who led the Upper Towns. Eventually, leaders like Major Ridge (as The Ridge was known after his military service), his son John Ridge, and his nephews Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie came to believe they needed to negotiate the best deal with the government. They believed removal would happen anyway. Other supporters of moving were John Walker, Jr., David Vann, and Andrew Ross (brother of Principal Chief John Ross). They agreed to the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. This led to the Cherokee removal in 1838–1839.

Later Events

Tecumseh's Visit

In November 1811, Shawnee chief Tecumseh returned to the South. He hoped to get support from southern tribes. His goal was to push back the Americans and bring back old ways. He came with representatives from the Shawnee, Muscogee, Kickapoo, and Sioux peoples. Tecumseh's speeches in the towns of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Lower Muscogee did not gain much support. But he did attract some younger warriors from the Upper Muscogee.

The Cherokee group led by The Ridge visited Tecumseh's council. They strongly opposed his plans. Tecumseh canceled his visit to the Cherokee Nation. This was because The Ridge threatened him with death if he went there. However, during his tour, Tecumseh was joined by 47 Cherokee and 19 Choctaw. They likely went north with him when he returned to the "Northwest Territory."

War with the Creek

Tecumseh's mission started a religious movement. Anthropologist James Mooney called it the "Cherokee Ghost Dance" movement. It was led by the prophet Tsali of Coosawatee, a former Chickamauga warrior. He later moved to the western North Carolina mountains. U.S. forces executed him in 1838 for fighting against the Removal.

Tsali met with the national council at Ustanali. He argued for war against the Americans. He convinced some leaders until The Ridge spoke. The Ridge argued even better against war. He called for supporting the Americans in the coming war with the British and Tecumseh's alliance. During the War of 1812, William McIntosh of the Lower Muscogee asked for Cherokee help in the Creek War. This was to stop the "Red Sticks" (Upper Muscogee). More than 500 Cherokee warriors served under Andrew Jackson in this effort. They fought against their former allies.

A few years later, Major Ridge led a group of Cherokee cavalry. They joined 1,400 Lower Muscogee warriors under McIntosh. This was during the First Seminole War in Florida. They were allied with U.S. Army troops, Georgia militia, and Tennessee volunteers. They went into Florida to fight the Seminoles, refugee Red Sticks, and escaped slaves.

Warriors from the Cherokee Nation East traveled to the lands of the Old Settlers (Cherokee Nation West) in Arkansas Territory. They helped them during the Cherokee-Osage War of 1817–1823. In this war, they fought against the Osage. After the Seminole War, Cherokee warriors, with one exception, did not fight again in the Southeast. This was until the American Civil War. Then, William Holland Thomas raised the Thomas Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders in North Carolina to fight for the Confederacy.

In 1830, the State of Georgia took land in its south. This land had belonged to the Cherokee since the end of the Creek War. It was separated from the rest of the Cherokee Nation by a large part of Georgia. Georgia began to divide it among settlers. Major Ridge led a group of 30 south. They drove the settlers out of their homes on what the Cherokee considered their land. They burned all buildings to the ground, but no one was harmed.

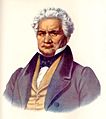

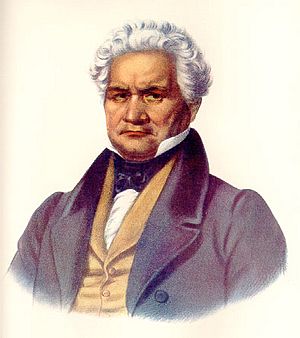

Images for kids

-

The Ridge (Ganundalegi), also known as Pathkiller (Nunnehidihi). This picture is from History of the Indian Tribes of North America.