Cherokee removal facts for kids

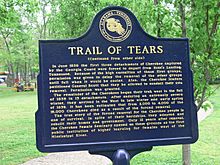

The Cherokee removal, often called the Trail of Tears, was a sad and difficult time for the Cherokee people. Between 1836 and 1839, about 16,000 Cherokee and 1,000–2,000 of their slaves were forced to leave their homes. These homes were in places like Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama. They were made to move far away to the Indian Territory (which is now Oklahoma) in the western part of the United States.

Many people died during this forced journey. It's thought that around 4,000 Cherokee and an unknown number of slaves lost their lives. The Cherokee call this event Nu na da ul tsun yi, meaning "the place where they cried." Another name is Tlo va sa, or "our removal."

Other Native American groups in the United States also faced similar forced moves. These included the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee (Creek), and Seminole tribes. The Seminole in Florida fought against being moved for many years.

The phrase "Trail of Tears" is now used for similar events that happened to other Native American groups. It first described the forced move of the Choctaw Nation in 1831.

Contents

Background of the Removal

In 1835, a count was made of the Cherokee people living in the Southeast. It showed about 16,542 Cherokee, 201 white people married to them, and 1,592 slaves. This made a total of 18,335 people.

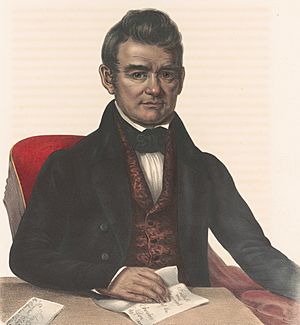

There were growing problems between the Cherokee and white settlers. White settlers wanted the Cherokee land because it had gold and good soil for growing cotton. In October 1835, Principal Chief John Ross, the leader of the Cherokee, was kidnapped from his home. He was taken by a group from the Georgia militia.

After being released, Chief Ross and other tribal leaders went to Washington, D.C. They wanted to protest this action and President Andrew Jackson's plan to move them. Chief Ross tried to make a deal with President Jackson. He offered to give up some land for money and land in the west. Jackson refused this deal. Ross then suggested $20 million for the land, and eventually, the U.S. Senate decided on the price.

An agent for the U.S. government, John F. Schermerhorn, met with a small group of Cherokee who disagreed with Chief Ross. This meeting happened at the Cherokee capital, New Echota, Georgia. On December 29, 1835, this small group signed a treaty called the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty traded Cherokee land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River.

However, the elected Cherokee leaders and most of the Cherokee people did not agree with this treaty. In February 1836, two large meetings were held where about 13,000 Cherokee signed lists saying they were against the treaty. Chief Ross sent these lists to Congress. But, a slightly changed version of the treaty was approved by the U.S. Senate by just one vote on May 23, 1836. President Jackson then signed it into law. The treaty gave the Cherokee until May 1838 to move themselves to Indian Territory.

Why Cotton Farming Mattered

Before the cotton gin was invented, growing cotton was very hard work. It took a long time to remove the sticky seeds from the cotton. This made it not very profitable. But in 1793, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin. This machine made it much easier to clean cotton.

Because of the cotton gin, cotton farming grew a lot in the South, especially near North Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia. Cotton production increased hugely between 1830 and 1850. This success earned the South the nickname "King Cotton."

The Cherokee Nation had valuable farming land. This land was perfect for growing cotton because of the climate. It would have been very important for the growing cotton industry. White settlers wanted this land to grow more cotton and make money.

Most Cherokee families had small farms and grew only what they needed. But some Cherokee started growing cotton to sell. This made them a threat to white settlers who wanted to profit from the cotton industry. The settlers wanted to take over the land and control the cotton market. This desire for land helped push the idea of moving the Cherokee.

Georgia and the Cherokee Nation's Land

In the early 1800s, the United States was growing fast. This caused problems with Native American tribes living inside state borders. States like Georgia wanted to control all the land within their boundaries. But Indian tribes did not want to move or lose their unique ways of life.

In 1802, Georgia gave up its land claims in the west (which became Alabama and Mississippi). In return, the U.S. government promised to eventually make treaties to move the Indian tribes living in Georgia. This would give Georgia full control of its land.

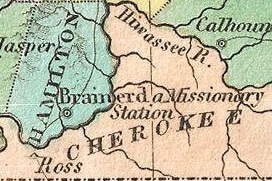

However, the Cherokee, whose lands were in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama, refused to move. They set up their capital at New Echota in 1825. In 1827, led by Chief John Ross, the Cherokee wrote their own constitution. They declared the Cherokee Nation to be a free and independent nation.

John Ross became the first elected Principal Chief. In 1828, the Cherokee government made a law. It said that anyone who signed a land agreement with the U.S. without the Cherokee government's permission would be seen as a traitor and could be put to death.

The Cherokee land was very valuable. It was a good place for future roads and railroads connecting the mountains to rivers like the Tennessee River. This area is still important for transportation today. Georgia taking these lands meant the Cherokee Nation lost out on this wealth.

The Cherokee lands in Georgia were also important because they were the easiest way to travel between the Chattahoochee River and the Tennessee River. From the Tennessee River, people could travel by water to other parts of the country.

These problems between Georgia and the Cherokee Nation became worse when gold was found near Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1828. This started the Georgia Gold Rush. People hoping to find gold began going onto Cherokee lands without permission. This put more pressure on Georgia to get rid of the Cherokee.

In 1830, Georgia tried to make its laws apply to Cherokee lands. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the Court said the Cherokee were not a fully independent nation. So, the Court would not hear their case. But in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not make laws in Cherokee territory. Only the U.S. government had power over Indian affairs.

President Andrew Jackson did not agree with the Supreme Court's ruling. He was determined to move the Cherokee. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This law gave Jackson the power to make treaties to exchange Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson used the dispute with Georgia to pressure the Cherokee to sign a removal treaty.

Because of Georgia's laws, the Cherokee Nation moved its capital to the Red Clay Council Grounds in Tennessee.

The Treaty of New Echota

After Andrew Jackson was re-elected president in 1832, some Cherokee leaders started to think differently about removal. These leaders included Major Ridge, his son John Ridge, and nephews Elias Boudinot and Stand Watie. They became known as the "Treaty Party." They believed it was best to make a deal with the U.S. government before things got worse.

Meanwhile, Georgia began holding lotteries to divide up Cherokee lands among white Georgians.

However, Principal Chief John Ross and most of the Cherokee people were strongly against moving. Chief Ross even canceled tribal elections. The Cherokee Nation became split into two groups: those who followed Ross (the National Party) and those who supported the Treaty Party.

Chief Ross wrote a strong letter to Congress. He said the treaty took away their private property and their freedom. He wrote that they had "neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own." He felt they were being treated as if they were not part of the human family.

In 1835, President Jackson sent Reverend John F. Schermerhorn to make a treaty. The U.S. government offered the Cherokee Nation $4.5 million to move. But the Cherokee National Council rejected these terms in October 1835. Chief Ross tried to negotiate new terms, but he was told to deal with Schermerhorn.

Schermerhorn then held a meeting with the pro-removal Cherokee leaders at New Echota, Georgia. Only about five hundred Cherokee attended. On December 30, 1835, twenty-one people signed the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty gave up all Cherokee land east of the Mississippi River. In return, the Cherokee would get $5 million, money for education, and land in Indian Territory. It also said Cherokee could stay and become citizens on 160 acres of land, but President Jackson later removed this part.

Chief Ross and the Cherokee National Council said the treaty was a fraud. But Congress still approved it on May 23, 1836, by only one vote.

The Removal Process

The Cherokee removal happened in three main steps. First, some Cherokee who agreed with the treaty moved on their own. This was called the voluntary removal. Most Cherokee, including Chief John Ross, were very angry and did not want to move. They thought the government would not force them to leave.

But the U.S. Army was sent in, and the forced removal began. The Cherokee were violently gathered into special camps during the summer of 1838. Moving them west was delayed because of very hot weather and a lack of rain. In the fall, the Cherokee finally agreed to move themselves west. This was done under the leadership of Chief Ross, and it was called the reluctant removal.

Voluntary Removal Stage

The treaty gave the Cherokee two years to move to Indian Territory on their own. President Andrew Jackson sent General John E. Wool to help with this. But when General Wool arrived, he saw that almost all the Cherokee were against the treaty. They refused to accept government help to move.

General Wool was frustrated because no one wanted to leave willingly. During this time, some Cherokee who supported the treaty tried to convince others to accept government help. But Chief John Ross told his people to keep refusing any help. He said that taking help meant agreeing to the treaty.

Seeing that their efforts were not working, about 2,000 Cherokee (mostly from the Ridge faction) accepted government money and moved west. They left about 13,000 Cherokee behind who still opposed the treaty. Many moved as families or individuals. Some groups also moved together. For example, Major Ridge and Stand Watie left with a group of 466 Cherokee in March 1837.

Forced Removal Stage

Many Americans were upset by the treaty and asked the government not to force the Cherokee to move. For example, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote a letter to President Martin Van Buren in April 1838. He asked him not to harm the Cherokee Nation.

But as the May 23, 1838, deadline for voluntary removal got closer, President Van Buren ordered General Winfield Scott to lead the forced removal. General Scott set up his headquarters in Charleston, Tennessee. He arrived with about 7,000 U.S. Army and state militia soldiers.

General Scott told his troops to be kind to the Cherokee. He ordered them to arrest any soldier who hurt or insulted a Cherokee person. The soldiers began gathering Cherokee people in Georgia on May 26, 1838. Ten days later, they started in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Alabama.

Men, women, and children were taken from their homes at gunpoint over three weeks. They were gathered into crowded camps, often with very few of their belongings. About 1,000 Cherokee hid in the mountains. Some who owned private land also avoided being taken.

The Cherokee were then marched to places like Ross's Landing (Chattanooga, Tennessee) and Gunter's Landing (Guntersville, Alabama) on the Tennessee River. From there, they were forced onto boats. However, a drought caused low water levels in the rivers. This made boat travel very difficult, with many deaths and people leaving the groups. General Scott stopped these army-led removals.

Because of the deaths and people leaving, General Scott stopped the Army's removal efforts. The remaining Cherokee were put into eleven internment camps. These camps were in places like Fort Cass and Ross's Landing.

The Cherokee stayed in these camps during the summer of 1838. Many became sick with diseases like dysentery, and 353 people died. A group of Cherokee asked General Scott to delay the journey until cooler weather. He agreed. Chief Ross, finally accepting that they had to move, managed to get the U.S. government to let the Cherokee Council manage the rest of the removal. General Scott agreed to pay for the remaining 11,000 Cherokee to be moved under Chief Ross's leadership.

Reluctant Removal Stage

Chief John Ross made sure he was in charge of the removal process. He worked with other Cherokee leaders, who gave him full responsibility. He quickly made a plan. He organized 12 wagon trains, each with about 1,000 people. These trains were led by experienced Cherokee leaders. Each train had doctors, interpreters, and other helpers, even grave diggers. Chief Ross also bought a steamboat for his family and other leaders to travel more comfortably.

Even with these better plans, many people still died from disease and exposure to the weather. These groups had to travel through many states, including Kentucky, Illinois, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Missouri. Their final destination was Oklahoma. One main route went through Chattanooga, Tennessee, then northwest through Kentucky and Illinois, and southwest through Missouri. The whole trip was about 2,200 miles long.

The Cherokee faced freezing temperatures, snowstorms, and pneumonia. The harsh journey and bad weather caused about 4,000 deaths, though the exact number varies in different estimates.

Deaths and Numbers

The number of people who died on the Trail of Tears has been estimated differently. An American doctor, Elizur Butler, who traveled with one group, estimated 2,000 deaths in the Army camps and another 2,000 on the trail. His total of 4,000 deaths is often used.

A study in 1973 estimated 2,000 total deaths. Another study in 1984 said 6,000 people died. The Smithsonian anthropologist James Mooney also used the 4,000 figure, which was about one-quarter of the tribe. About 16,000 Cherokee were counted in 1835, and about 12,000 moved in 1838. This means about 4,000 people were not accounted for. Some 1,500 Cherokee stayed in North Carolina, and more in South Carolina and Georgia, so the highest death numbers might not be accurate. Also, nearly 400 Creek Indians who had not been moved earlier joined the Cherokee removal.

It was also hard to count the exact number of deaths because of problems with Chief John Ross's expense reports. He claimed rations for more Cherokee than the Army counted. The Van Buren government refused to pay Ross at first, but a later president approved paying him over $500,000 in 1842.

Some Cherokee traveled back and forth more than once. Many people who left the Army's boat groups later joined the wagon trains led by Ross. People also moved between groups, and these changes were not always recorded.

During the journey, it is said that the people would sing "Amazing Grace". This Christian hymn had been translated into Cherokee. The song became a special anthem for the Cherokee people.

Aftermath of the Removal

The Cherokee who were moved first settled near Tahlequah, Oklahoma. The disagreements caused by the Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears led to the killings of Major Ridge, John Ridge, and Elias Boudinot. Only Stand Watie escaped that day. Over time, the Cherokee Nation's population grew again. Today, the Cherokee are the largest Native American group in the United States.

Not all Cherokee were removed. Some Cherokee lived on private land that they owned, not land owned by the tribe. These people were not forced to move. In North Carolina, about 400 Cherokee, led by Yonaguska, lived on land owned by a white man named William Holland Thomas. He had been adopted by the Cherokee as a boy. So, these Cherokee were not forced to leave. They were joined by other small groups. These North Carolina Cherokee became the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. They numbered about 1,000 people.

A local newspaper in 1840 said that between 900 and 1,000 Cherokee were still in North Carolina. It said they were "a great annoyance to the citizens" who wanted to buy land there. The newspaper reported that President Jackson said they were "free to go or stay."

The Trail of Tears is seen as a very sad event in American history. To remember it, the U.S. Congress named the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail in 1987. It covers 2,200 miles across nine states.

In 2004, Senator Sam Brownback introduced a resolution to apologize to all Native Peoples for past U.S. government policies. It passed in the U.S. Senate in 2008.

As of 2014, members of the Cherokee Nation can ask for special heritage seeds for a type of bean. These beans were carried by the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears. This is part of the Cherokee Seed Project.

In Popular Culture

- The band Paul Revere & the Raiders released a song in the 1970s called "Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian)". It remembered the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation.

- The country-rock group Southern Pacific recorded a song called "Trail of Tears" on their 1988 album Zuma.

- In 1974, John and Terry Talbot of Mason Proffit wrote and recorded their song "Trail of Tears" on the album The Talbot Brothers.

- The Swedish rock band Europe mentions the Trail of Tears in their song "Cherokee" from their album The Final Countdown.

- The American composer James Barnes wrote a piece for band called Trail of Tears (1989). It shows the journey of the Cherokee people. The piece includes a sad poem spoken in the Cherokee language.

- Guitarist Eric Johnson released a song called "Trail of Tears" on his 1986 album Tones.

- A Parchment of Leaves, a novel by Silas House, uses the Cherokee Removal as a main part of its story.

- The novel Through the Trail of Tears by Gloria V. Casañas also has these events as a major theme. It is told through parts of a fictional diary.

Documentary

- The Trail of Tears: Cherokee Legacy is a documentary from 2006 directed by Chip Richie.

|

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |