Eli Whitney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eli Whitney

|

|

|---|---|

1822 portrait of Whitney by Samuel Morse

|

|

| Born |

Eli Whitney Jr.

December 8, 1765 Westborough, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America

|

| Died | January 8, 1825 (aged 59) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Education | Yale College |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Spouse(s) |

Henrietta Frances Edwards

(m. 1817) |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Whitney family |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | Interchangeable parts, cotton gin |

| Signature | |

|

|

Eli Whitney Jr. (born December 8, 1765 – died January 8, 1825) was a clever American inventor. He is most famous for creating the cotton gin in 1793. This invention was a big deal during the Industrial Revolution and changed the economy of the Southern United States. His cotton gin made it much easier to process a type of cotton called "upland short cotton." This made cotton farming very profitable, which unfortunately increased the demand for workers in the Southern states. Even though his invention had a huge impact, Eli Whitney faced many legal challenges trying to protect his patent for the cotton gin. Because of these problems, he didn't make as much money as he hoped from it. Later, he focused on working with the government to make muskets (a type of rifle) for the new United States Army. He kept inventing and making weapons until he passed away in 1825.

Contents

Eli Whitney's Early Life and Education

Eli Whitney was born in Westborough, Massachusetts, on December 8, 1765. He was the oldest child of Eli Whitney Sr., who was a successful farmer.

When Eli was 11, his mother passed away. By the time he was 14, during the American Revolutionary War, he was already running a successful business making nails in his father's workshop!

Eli really wanted to go to college. However, his stepmother didn't support this idea. So, Eli worked hard as a farm helper and a school teacher to save enough money. He studied at Leicester Academy and with a teacher named Rev. Elizur Goodrich. He finally entered Yale University in 1789 and graduated in 1792.

After college, Eli planned to study law. But he needed more money. He accepted a job offer to be a private tutor in South Carolina. On his journey, he met the widow of a famous war hero, Mrs. Catherine Littlefield Greene. She invited Eli to visit her large farm, called Mulberry Grove, in Georgia. There, he met Phineas Miller, who would later become his business partner.

Eli Whitney's Amazing Inventions

Eli Whitney is famous for two big ideas that changed the United States in the 1800s. These were the cotton gin (invented in 1793) and his strong support for interchangeable parts. The cotton gin completely changed how cotton was harvested in the Southern states. Meanwhile, interchangeable parts transformed factories in the Northern states, making manufacturing much more efficient.

How the Cotton Gin Changed Cotton Farming

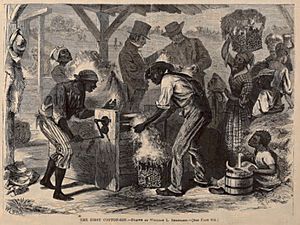

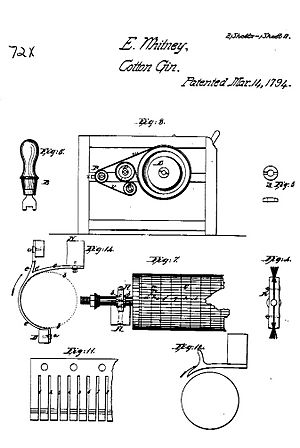

The cotton gin is a machine that quickly removes seeds from cotton fibers. Before this invention, separating cotton seeds was very hard work, usually done by hand. The word "gin" is actually short for "engine"!

While staying at Mrs. Greene's farm, Eli Whitney heard people talking about how difficult it was to clean cotton. He quickly got to work and, in just a few weeks, he built a model of his new machine. The cotton gin used a wooden drum with hooks that pulled cotton fibers through a screen. The seeds were too big to pass through the screen and fell out.

This invention was a game-changer! A single cotton gin could clean up to 55 pounds (about 25 kg) of cotton every day. This made cotton farming much more profitable in the Southern United States. Unfortunately, this also increased the demand for workers on cotton farms.

Eli Whitney applied for a patent for his cotton gin in 1793. However, he faced many problems with people copying his invention. He and his business partner, Phineas Miller, wanted to charge farmers for cleaning their cotton, instead of selling the machines. But it was easy for others to build similar machines, and many people did. This led to many lawsuits, and Whitney's company eventually went out of business in 1797.

Even though the cotton gin didn't make Eli Whitney rich, it made him famous. His invention had a huge impact on the Southern economy. Cotton became the most important crop, and the United States started exporting massive amounts of cotton to Europe and other places. This period was sometimes called the "King Cotton" era because cotton was so important.

The Idea of Interchangeable Parts

Eli Whitney is often given credit for inventing interchangeable parts, but this idea actually existed before him. His important role was in promoting and making this idea popular, especially for making muskets (guns).

What are interchangeable parts? Imagine if every part of a machine was made exactly the same. If one part broke, you could easily replace it with another identical part, instead of having to make a new custom part or even a whole new machine. This makes repairs much faster and manufacturing much cheaper!

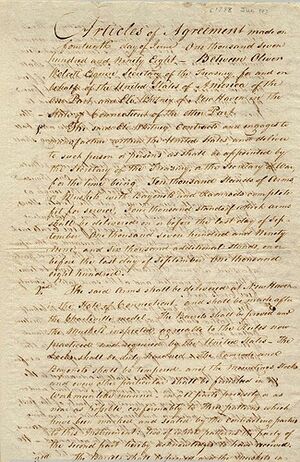

Many people worked on this idea over time. Eli Whitney became a strong supporter of it when he got a contract from the U.S. government in 1798. He was hired to make 10,000 to 15,000 muskets for the army. At this time, his cotton gin business was struggling, and he needed money.

Whitney promised to deliver the muskets quickly using interchangeable parts. However, he faced many challenges and delays. It took him much longer than expected to fulfill the contract. Some historians believe that his early demonstrations of interchangeable parts were "staged" to impress government officials and buy him more time.

Despite the difficulties, Whitney's work helped to popularize the idea of interchangeable parts. This concept later became a key part of the "American system of manufacturing." It helped factories make many products quickly and efficiently, which was very important for the country's growth.

The Milling Machine's Development

Eli Whitney was also involved in the early development of the milling machine. This is a tool used to shape metal and other materials very precisely. However, he wasn't the only one working on it. Many inventors were developing similar machines around the same time, between 1814 and 1818. So, it's hard to say that one person alone invented the milling machine.

Later Life and Lasting Legacy

Eli Whitney was very good at making friends with important people. He used his connections from Yale University to help his arms business grow. These connections included government officials and powerful leaders.

In 1817, he married Henrietta Edwards. Her family was also very well-known and connected in Connecticut. These family ties were helpful for his business, especially since he relied on government contracts.

Eli Whitney passed away on January 8, 1825, in New Haven, Connecticut, shortly after his 59th birthday. He had been ill with prostate cancer. It is said that he even invented some devices to help ease his pain during his illness.

His son, Eli Whitney III (also known as Eli Whitney Jr.), later took over his father's armory. He also played a big part in building the water system for New Haven, Connecticut.

Today, Yale University has a special program for older students called the Eli Whitney Students Program. It's named after him because he started his studies at Yale when he was 23 and graduated with honors in just three years.

See also

In Spanish: Eli Whitney para niños

In Spanish: Eli Whitney para niños

- Whitney family

- Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Eli Whitney Museum

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |