Cherokee Nation (1794–1907) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cherokee Nation ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ

Tsalagihi Ayeli

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1794–1907 | |||||||||||||||||

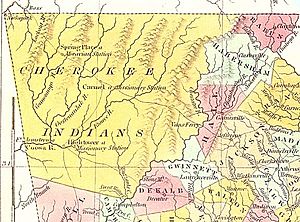

Southeastern U.S. and Indian territories, including Cherokee, Creek, and Chickasaw; 1806

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Status | Sovereign state (1794-1865) United States region (1865-1907) |

||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Cherokee | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Autonomous tribal government | ||||||||||||||||

| Principal Chief | |||||||||||||||||

|

• 1794–1907

|

Principal Chief | ||||||||||||||||

|

• 1794–1905

|

Tribal Council | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-colonial to early 20th century | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Created with the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse

|

7 November 1794 1794 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• New Echota officially designated capital city

|

12 November 1825 | ||||||||||||||||

| 29 December 1835 | |||||||||||||||||

|

• Cherokee Trail of Tears

|

1838–1839 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Tahlequah becomes new official capital

|

6 September 1839 | ||||||||||||||||

|

• Disbanded by US Federal Government

|

16 November 1907 1907 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | US dollar | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States -Oklahoma |

||||||||||||||||

The Cherokee Nation (in Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ, pronounced Tsalagihi Ayeli) was a self-governing Native American group in North America. It was officially recognized from 1794 to 1907. People living there often called it "The Nation."

The United States government ended the Cherokee Nation's official status in 1907. This happened just before Oklahoma became a state. Later, in the late 1900s, the Cherokee people formed a new government. This government is known today as the Cherokee Nation. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and also the Cherokee Nation, had never truly stopped existing.

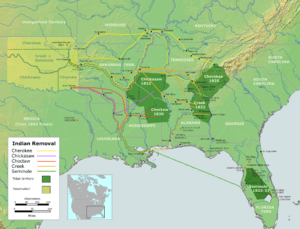

The Cherokee Nation included the Cherokee people from the Qualla Boundary and the southeastern United States. It also included those who moved to Indian Territory (around 1820). Many were forced to move by the U.S. government during the Trail of Tears in the 1830s. The Nation also welcomed descendants of the Natchez, Lenape, and Shawnee peoples. After the Civil War, formerly enslaved people and their families also became part of the Cherokee Nation.

The Cherokee Nation was seen as its own independent government. During the American Civil War, many Cherokee leaders sided with the Confederacy. Because of this, the U.S. required a new peace treaty after the war. This treaty also gave freedom to enslaved people within the Cherokee Nation. Later, the U.S. Congress passed the Dawes Act. This law aimed to break up Native American governments and land claims. It was part of the plan to make Oklahoma a state in 1907. After land was divided among families, all Cherokee people became citizens of the state and the United States.

Contents

A Look Back: History of the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee people called themselves the Ani-Yun' wiya. In their language, this means "leading" or "principal" people. Before 1794, the Cherokee did not have one big national government. Instead, they lived in many separate towns and clans. Their society was based on a matrilineal kinship system. This means family lines were traced through mothers.

Cherokee towns were spread out in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Each town was self-governing. Leaders were chosen when needed to talk with French, British, and later, U.S. officials. The Cherokee called this leader "First Beloved Man" or Uku. The English translated this as "chief".

The chief's main job was to lead talks with the Europeans who were moving into their lands. Hanging Maw was one such chief recognized by the U.S. government. However, most Cherokee people did not see him as their main leader.

Forming a United Nation

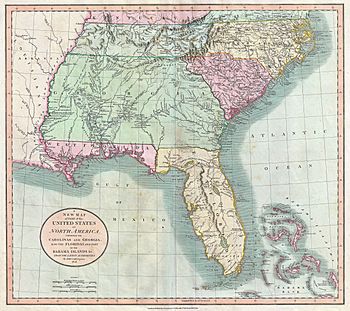

At the end of the Cherokee–American wars in 1794, Little Turkey became the "Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation". All the towns recognized him. At this time, Cherokee communities were in lands claimed by North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and eastern Tennessee.

A group called the Chickamauga Cherokee (or Lower Cherokee) had moved away earlier. They were led by War Chief Dragging Canoe. They lived in a mountainous area that later became part of northeastern Alabama.

U.S. President George Washington wanted Native Americans in the Southeast to adopt European-American ways of life. This was called "civilizing" them. U.S. agents encouraged Native Americans to stop sharing land and start individual farms. They also introduced pigs and cattle, which replaced deer as a main food source.

Americans also taught Cherokee men to fence and plow land. Traditionally, Cherokee women did most of the farming. Women were taught weaving. Over time, blacksmiths, mills, and cotton farms (using enslaved labor) were set up.

After Little Turkey, Black Fox (1801–1811) and Pathkiller (1811–1827) became Principal Chiefs. Both had been warriors with Dragging Canoe. In 1809, the Cherokee officially reunited, ending the "separation" period.

New Leaders and Education

Three important veterans of the Cherokee–American wars became key leaders. They were James Vann, The Ridge, and Charles R. Hicks. These leaders wanted the Cherokee people to adopt some European-American customs. They supported formal education for young people and new farming methods.

In 1801, they invited Moravian missionaries to their land. These missionaries taught Christianity and "civilized life." The Moravians and later Congregationalist missionaries also ran boarding schools. Some students even went to a school in Connecticut.

Charles R. Hicks was a very important leader. He was the main chief from 1813–1827. He also took part in the Creek War, a civil war among the Creek people. This war happened at the same time the U.S. was fighting in the War of 1812.

Creating a Government

The Cherokee Nation—East started creating electoral districts in 1817. By 1822, they had a Supreme Court. In 1827, the Cherokee Nation adopted a written constitution. This constitution set up a government with three parts: a law-making group (legislative), a leader (executive), and courts (judicial). The Principal Chief was chosen by the National Council, which was the law-making body. The Cherokee Nation—West adopted a similar constitution in 1833.

After the Trail of Tears, the reunited Cherokee Nation approved a new constitution. This happened in Tahlequah, Oklahoma on September 6, 1839. This event is celebrated every Labor Day weekend during the Cherokee National Holiday.

The Forced Removal

In 1802, the U.S. government promised Georgia that it would remove Native Americans from Georgia's lands. In return, Georgia gave up its claims to western lands. European Americans wanted more land in the Deep South for cotton farms. The invention of the cotton gin made growing cotton very profitable.

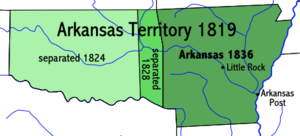

In 1815, the U.S. government created a Cherokee Reservation in the Arkansaw district. They tried to convince the Cherokee to move there voluntarily. The Cherokee who moved became known as the "Old Settlers" or Western Cherokee.

Through treaties in 1817 and 1819, the Cherokee traded their lands in Georgia, Tennessee, and North Carolina for lands west of the Mississippi River. However, most Cherokee refused to leave their homes. In 1830, the United States Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This law forced Native Americans to give up their lands. About one-third of the remaining Native Americans left voluntarily. The rest were forced out by government troops and the Georgia militia.

Most of the new Cherokee settlements were near Tahlonteeskee, Oklahoma, which was the western capital.

Civil War and Rebuilding

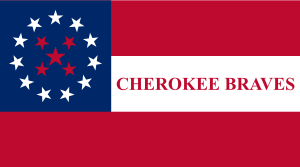

During the American Civil War, the Cherokee Nation faced a difficult choice. Some wanted to stay neutral. Others wanted to join the Union or the Confederacy. Two important Cherokee leaders, John Ross and Stand Watie, owned enslaved people. Watie believed the Cherokee should side with the Confederacy. Ross wanted to remain neutral. The memory of the Trail of Tears made the decision even harder. Within the first year, most of the Nation decided to support the Confederacy.

Many small battles took place in the Cherokee Nation–West. About 3,000 out of 21,000 Cherokee served as soldiers for the Confederacy. Some notable Cherokee who served were:

- William Penn Adair (1830–1880), a Cherokee senator and diplomat.

- Nimrod Jarrett Smith (1837–1893), who later became a Principal Chief.

- Confederate General Stand Watie (1806–1871), who signed the Treaty of New Echota. He led the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles and was the last Confederate general to surrender in June 1865.

After the war, the U.S. made new treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes. These tribes had to agree that their old treaties with the U.S. were no longer valid because they had sided with the Confederacy. This allowed the U.S. to take more land. The new treaty also required the Cherokee to free their enslaved people. These formerly enslaved people, called freedmen, were offered citizenship and land within the Cherokee Nation if they chose to stay.

A study in 2020 showed that formerly enslaved people in the Cherokee Nation did very well. They received free land, unlike those in the former Confederate states. This led to less racial inequality in the Cherokee Nation. Black people had higher incomes, more people could read, and more children went to school.

The End of the Nation's Government

In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison stopped the leasing of land in the Cherokee Outlet. The money from these leases helped the Cherokee Nation protect its lands.

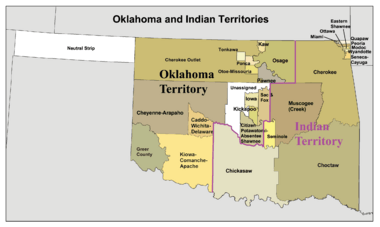

From 1898 to 1906, the U.S. government began to dismantle the Cherokee Nation's government. This was to prepare for the Indian Territory to become part of the new state of Oklahoma. In response, leaders of the Five Civilized Tribes tried to create a new state called State of Sequoyah in 1905. It would have its own Native American constitution. However, the U.S. Congress did not approve this idea. The Cherokee Nation's government was officially dissolved in 1906.

After this, the Cherokee government was not clearly defined. The U.S. government sometimes appointed chiefs just to sign treaties. As problems with this setup grew, the Cherokee wanted a more permanent government. In 1934, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration passed the Indian Reorganization Act. This law encouraged tribes to restart their governments. On August 8, 1938, the Cherokee held a meeting in Fairfield, Oklahoma. They elected a new Chief and reformed the Cherokee Nation.

Life in the Indian Territory

The Cherokee Nation was divided into nine districts. These were Canadian, Cooweescoowee, Delaware, Flint, Goingsnake, Illinois, Saline, Sequoyah, and Tahlequah.

The Cherokee Capital

Tahlequah was founded in 1838 as the new capital of the united Cherokee Nation. It was named after Great Tellico, an important Cherokee town in Tennessee. Today, signs in Tahlequah are often in both English and the Cherokee language (using the alphabet created by Sequoyah).

The Cherokee National Capitol Building

The Cherokee National Capitol building was built between 1867 and 1869. It was designed by C. W. Goodlander in the 'late Italianate' style. It housed the nation's court and other offices. In 1961, the U.S. Department of Interior named it a National Historic Landmark.

People of the Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation was made up of different groups of people. These included the Cherokee Nation–West, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Cherokee Nation–East (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians). These three groups became the main federally recognized tribes of Cherokee in the 20th century.

The Delaware People

In 1866, some Delaware (Lenape) people moved to the Cherokee Nation from Kansas. They had been sent to Kansas in the 1830s. They settled in the northeast part of the Indian Territory and joined the Cherokee Nation in 1867. The Delaware Tribes managed their own affairs within the Cherokee Nation's lands.

The Natchez People

The Natchez are a Native American people who originally lived near present-day Natchez, Mississippi. In the mid-1700s, French colonists defeated them. Many survivors were sold into slavery. Others found safety with allied tribes, including the Cherokee.

The Shawnee People

A group of Shawnee people, known as the Loyal Shawnee or Cherokee Shawnee, moved to Indian Territory with the Seneca people in 1831. They were called "Loyal" because they fought for the Union during the American Civil War. After the war, European-American settlers moved onto their lands.

In 1869, the Cherokee Nation and the Loyal Shawnee agreed that 722 Shawnee would become Cherokee citizens. They settled in Craig and Rogers counties.

Swan Creek and Black River Chippewa

The Anishinaabe-speaking Swan Creek and Black River Chippewa bands were moved from southeast Michigan to Kansas in 1839. After Kansas became a state and the Civil War ended, settlers pushed them out. Like the Delaware, these two Chippewa bands moved to the Cherokee Nation in 1866. They were very few in number and eventually merged with the Cherokee.

Cherokee Freedmen

The Cherokee Freedmen were formerly enslaved African Americans who had been owned by Cherokee citizens. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This gave citizenship to all formerly enslaved people in the Confederate States, including those held by the Cherokee. To make peace with the Cherokee, the U.S. government required them to free their enslaved people. It also required them to offer full Cherokee citizenship to those who wanted to stay. This was guaranteed by a treaty in 1866.

Famous Cherokee Nation Citizens

This list includes important Cherokee people who lived in or were born into the original Cherokee Nation:

- Elias Boudinot, Galagina (1802–1839), a leader and speaker. He started the first Cherokee newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix.

- Ned Christie (1852–1892), a Cherokee Nation senator.

- Rear Admiral Joseph J. Clark (1893–1971), a U.S. Navy officer. He was the highest-ranking Native American in U.S. military history.

- Doublehead, Taltsuska (died 1807), a war leader during the Cherokee–American wars.

- Junaluska (around 1775–1868), a veteran of the Creek War. He saved President Andrew Jackson's life.

- John Ridge, Skatlelohski (1792–1839), son of Major Ridge, a leader who signed the New Echota Treaty.

- John Rollin Ridge, Cheesquatalawny, or "Yellow Bird" (1827–1867), grandson of Major Ridge, and the first Native American novelist.

- Clement V. Rogers (1839–1911), a Cherokee senator, judge, and cattleman.

- Will Rogers (1879–1935), a famous Cherokee entertainer, roper, journalist, and writer.

- John Ross, Guwisguwi (1790–1866), a veteran of the Red Stick War. He was the Principal Chief during the Removal and in the west.

- Redbird Smith (1850–1918), a traditionalist and political activist.

- William Holland Thomas, Wil' Usdi (1805–1893), a non-Native adopted into the tribe. He was the first Principal Chief of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

- Nancy Ward, Nanye-hi (around 1736–1822/4), a Beloved Woman and diplomat.

In Popular Culture

- The song "Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian)" by Paul Revere & the Raiders tells about the struggles of the Cherokee Nation.

|

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |