Stand Watie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stand Watie

|

|

|---|---|

|

ᏕᎦᏔᎦ

|

|

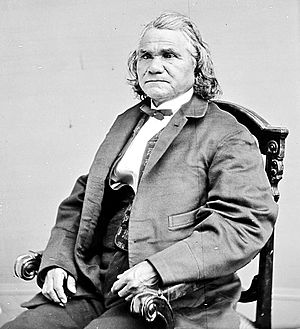

Watie, c. 1865

|

|

| 2nd Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation | |

| In office 1862–1866 |

|

| Preceded by | John Ross |

| Succeeded by | John Ross |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 12, 1806 Oothcaloga, Cherokee Nation (present-day Calhoun, Georgia), U.S. |

| Died | September 9, 1871 (aged 64) Delaware County, Indian Territory, U.S. |

| Resting place | Polson Cemetery, Delaware County, Oklahoma, U.S. 36°31′32.2″N 94°38′09.5″W / 36.525611°N 94.635972°W |

| Relatives | Elias Boudinot (brother) Elias C. Boudinot (nephew) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles |

| Battles | American Civil War |

Brigadier-General Stand Watie (Cherokee: ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, romanized: Degataga, lit. 'Stand firm') was an important Cherokee leader. He was born on December 12, 1806, and passed away on September 9, 1871. He also went by names like Standhope Uwatie and Isaac S. Watie.

Watie served as the second principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1862 to 1866. During the American Civil War, the Cherokee Nation sided with the Confederate States. Stand Watie became the only Native American Confederate general. He led Native American soldiers, mostly Cherokee, Muskogee, and Seminole fighters. He was the very last Confederate general to surrender at the end of the war.

Before the Cherokee people were forced to move to Indian Territory in the 1830s, Watie and his older brother Elias Boudinot signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. Most of the Cherokee tribe did not agree with this treaty. After the move, there was a lot of conflict and violence within the tribe. Stand Watie was one of the few leaders who survived these dangerous times.

After the Civil War, Watie led a group of Southern Cherokee to Washington, D.C.. They hoped to make peace and have their tribal divisions recognized. However, the United States government only negotiated with the Cherokee leaders who had supported the Union. Watie spent his last years away from politics, trying to rebuild his farm.

Contents

Early Life in the Cherokee Nation

Stand Watie was born on December 12, 1806, in a place called Oothcaloga. This area was part of the Cherokee Nation, which is now Calhoun, Georgia. His father, Uwatie, was a full-blood Cherokee. His mother, Susanna Reese, had a white father and a Cherokee mother.

Watie's birth name was Degataga, which means "standing firm" in English. His brothers were Gallagina (who later became Elias Boudinot) and Thomas Watie. They were close to their uncle Major Ridge and his son John Ridge, who were also important tribal leaders.

By 1827, Watie's father, David Uwatie, had become a successful farmer. He owned African-American slaves who worked on his land. After his father became a Christian, he changed his name to David Uwatie. He and Susanna renamed their son Degataga to Isaac. However, Degataga preferred to use "Stand," a loose translation of his Cherokee name. Later, the family shortened their last name to "Watie."

Stand Watie and his brothers and sisters learned to read and write English. They attended the Moravian mission school in Spring Place, which is now in Georgia.

Working for the Cherokee Phoenix

Stand Watie sometimes wrote articles for the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper. His older brother Elias was the editor of this newspaper from 1828 to 1832. The Cherokee Phoenix was the first Native American newspaper. It printed articles in both Cherokee and English.

The Indian Removal Act

Watie became involved in the problems caused by Georgia's strict laws against Native Americans. Gold was found on Cherokee lands in northern Georgia. This led to thousands of white settlers moving onto Native American lands. There was a lot of conflict.

In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This law aimed to move all Native Americans from the Southeast to lands west of the Mississippi River. In 1832, Georgia took most of the Cherokee land. This happened even though federal laws were supposed to protect Native Americans. The state even sent its militia to destroy the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper office. The newspaper had published articles against the forced removal.

Stand Watie and his brothers believed that the removal was going to happen no matter what. They thought it was best to secure Cherokee rights through a treaty before moving to Indian Territory. They were part of the Treaty Party leaders who signed the 1835 Treaty of New Echota. However, most of the Cherokee people were against being removed. The Tribal Council and Chief John Ross refused to approve the treaty.

Moving to Indian Territory

In 1835, Stand Watie, his family, and many other Cherokee people moved to Indian Territory. This area is now Oklahoma. They joined some Cherokee who had already moved there in the 1820s. These earlier settlers were known as the "Old Settlers."

The Cherokee who stayed in the East were later rounded up by the U.S. government. They were forced to move in 1838. This difficult journey became known as the "Trail of Tears." About 4,000 people died during this forced march.

After the removal, there was a lot of violence within the Cherokee tribe. Some Cherokee leaders who signed the treaty were targeted. Stand Watie, his brother Elias Boudinot, their uncle Major Ridge, and cousin John Ridge were all sentenced to death on June 22, 1839. Only Stand Watie survived these attacks. He made sure his brother Elias's children were sent to their mother's family in Connecticut for safety and education. Their mother, Harriet, had died in 1836.

The violence continued for years. In the 1840s, Stand Watie was involved in further conflicts. His brother Thomas Watie was killed in 1845. This was part of a cycle of violence that affected the tribe for a long time.

Stand Watie and the Civil War

In 1861, Principal Chief John Ross signed an agreement with the Confederate States. He hoped to prevent the Cherokee Nation from splitting apart. However, within a year, Ross and some of the tribal council felt this agreement was not working. In the summer of 1862, Ross moved the tribal records to Union-controlled Kansas. He then went to Washington, D.C., to meet with President Lincoln.

After Ross left, Stand Watie took his place as principal chief. However, Tom Pegg became the principal chief for the pro-Union Cherokee. After Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, Pegg called a special meeting of the Cherokee National Council. On February 18, 1863, they passed a law to free all slaves within the Cherokee Nation.

Many Cherokee people fled north to Kansas or south to Texas for safety. Those who supported the Confederacy took advantage of the situation. They elected Stand Watie as principal chief. Ross's supporters did not accept this election. Open fighting broke out between Confederate and Union Cherokee within Indian Territory. The situation was made worse by outlaws who didn't support either side.

After the Civil War ended, both groups of Cherokee sent representatives to Washington. Watie tried to get the U.S. government to recognize a separate "Southern Cherokee Nation," but this never happened.

Stand Watie was the only Native American to become a Confederate brigadier-general during the war. Many Cherokee leaders were worried about the U.S. government. They feared it might turn their lands into a new state called Oklahoma. Because of this, most of the Cherokee Nation decided to support the Confederacy. This was a practical choice, even though less than one-tenth of the Cherokee owned slaves.

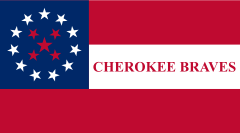

Watie formed a regiment of mounted infantry (soldiers on horseback). In October 1861, he became a Colonel in what became the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles.

Battles and Raids

Watie fought against Union troops. He also led his men in battles between different Cherokee groups. They attacked Cherokee civilians and farms. They also fought against the Creek, Seminole, and other tribes in Indian Territory who supported the Union.

Watie is well-known for his part in the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas. This battle took place from March 6–8, 1862. Watie's troops captured Union artillery (cannons). They also helped Confederate forces retreat safely from the battlefield. However, most of the Cherokees who had joined another regiment switched to the Union side.

In August 1862, after John Ross and his followers announced their support for the Union, Stand Watie was elected principal chief by the remaining Southern Confederate group. Even as support for the Confederacy among the Cherokee dropped, Watie continued to lead his cavalry. He was promoted to Brigadier-General on May 10, 1864.

Watie commanded the First Indian Brigade. This group included two regiments of Mounted Rifles and three battalions of Cherokee, Seminole, and Osage soldiers. These troops were based south of the Canadian River. They often crossed the river into Union territory.

Watie's forces fought in many battles and small fights in the western Confederate states. These included Indian Territory, Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, and Texas. It is said that Watie's group fought in more battles west of the Mississippi River than any other unit.

Watie played a key role in a major Confederate victory in Indian Territory. This was the Second Battle of Cabin Creek, which happened on September 19, 1864. He and General Richard Montgomery Gano led a raid that captured a Union supply train. They took about $1 million worth of wagons, mules, food, and other important supplies. During this raid, Watie's forces also attacked black haycutters. Union reports stated that Watie's soldiers "killed all the Negroes they could find," including wounded men.

During the war, General Watie's family and other Confederate Cherokee found safety in Rusk and Smith counties in east Texas. The Cherokee and their allies became a strong Confederate fighting force. They kept Union troops out of southern Indian Territory and much of north Texas throughout the war. However, they also spent a lot of time fighting other Cherokee.

In February 1865, the Confederate Army put Watie in charge of the Indian Division of Indian Territory. But by then, the Confederates were no longer able to fight effectively. On June 23, 1865, at Doaksville in the Choctaw Nation (now Oklahoma), Watie signed a cease-fire agreement. He was the last Confederate general in the field to surrender.

In September 1865, after the war ended, Watie went to Texas to see his wife Sallie. He also mourned the death of their son, Comisky, who had died at age 15. After the war, Watie was part of the Cherokee Delegation. This group worked to create new treaties with the United States.

Later Life and Family

The U.S. government saw that the two Cherokee groups (Union and Confederate supporters) could not agree. So, they decided to negotiate with them separately. This allowed the government to get many agreements from both sides. The new treaty required the Cherokee to free their slaves. The Southern Cherokee wanted the government to pay to move the Cherokee Freedmen from their lands. The Northern Cherokee suggested making them tribal members.

The U.S. government insisted that the Cherokee Freedmen would receive full rights as citizens. This included land and payments, just like other Cherokee. This treaty was signed by Chief Ross on July 19, 1866. The U.S. Senate approved it on July 27, just four days before Ross died.

The tribe was very divided over the treaty. A new chief, Lewis Downing, was elected. He was a wise leader who helped bring the Cherokee people back together. Even though some tensions lasted into the 20th century, the Cherokee did not have a long period of fighting among themselves like some other areas in the South.

After the treaty was signed, Watie lived in the Choctaw Nation for a short time. Soon after Downing was elected, Watie returned to the Cherokee Nation. He tried to stay out of politics and rebuild his life. He returned to Honey Creek, where he passed away on September 9, 1871. Stand Watie was buried in the old Ridge Cemetery, which is now called Polson's Cemetery. This cemetery is in what is now Delaware County, Oklahoma.

Stand Watie's Family

After moving to Indian Territory, Stand Watie married Sarah Bell on September 18, 1842. Their families had been friends for a long time. They had three sons: Saladin, Solon, and Cumiska. They also had two daughters, Minnee and Jacqueline. Sadly, all of their children passed away before their parents. Saladin died in 1868, and Solon died the next year. Both daughters passed away not long after their father. Sarah died in 1884.

Some historical records suggest that Stand Watie married four women during his life. These were Eleanor Looney, Elizabeth Fields, Isabella Hicks, and Sarah Caroline Bell. He had a child with Elizabeth Fields who was stillborn in 1836. Stand Watie and Sarah Bell married in 1842. They had five children together, but none of them had children of their own.

See also

In Spanish: Stand Watie para niños

In Spanish: Stand Watie para niños