John Ross (Cherokee chief) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Ross

|

|

|---|---|

| Koo-wis-gu-wi | |

John Ross ca. 1866

|

|

| Cherokee Nation Principal Chief | |

| In office 1829–1866 |

|

| Preceded by | William Hicks |

| Succeeded by | William P. Ross |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 3, 1790 Turkeytown, Alabama |

| Died | August 1, 1866 (aged 75) Washington, D.C. |

| Resting place | Ross Cemetery, Cherokee County, Oklahoma |

| Spouses | Quatie Brown Henley (c. 1790–1839) Mary Brian Stapler (1826–1865) |

| Relations | Great-granddaughter Mary G. Ross; Nephew William P. Ross; Niece Mary Jane (Ross) Ross |

| Children | 7 |

| Known for | opposition to Treaty of New Echota; Trail of Tears; Union supporter during American Civil War |

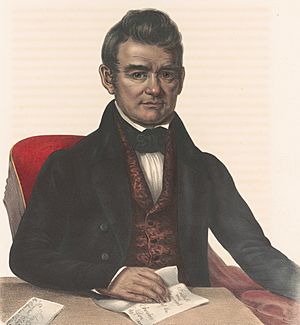

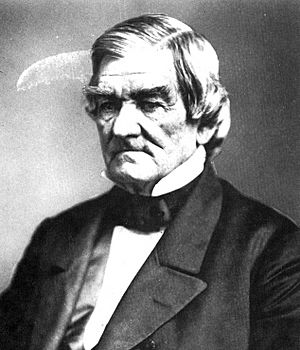

John Ross (Cherokee: ᎫᏫᏍᎫᏫ, romanized: Guwisguwi, lit. 'Mysterious Little White Bird'; October 3, 1790 – August 1, 1866) was a very important leader of the Cherokee Nation. He was their Principal Chief from 1828 to 1866, serving longer than anyone else. People sometimes called him the "Moses of his people." This meant he led his people through many difficult times. These included their forced move to Indian Territory and the American Civil War.

John Ross had a Cherokee mother and a Scottish father. His mother and grandmother were also part Scottish and part Cherokee. But they grew up in the Cherokee culture. The Cherokee people traced their family through the mother's side. So, children born to a Cherokee mother were considered part of her family and clan. This meant young John was raised as Cherokee. He also learned about British society and spoke both English and Cherokee. His parents sent him to schools that taught other mixed-race Cherokee children.

After finishing school, Ross became a US Indian agent in 1811. During the War of 1812, he served in a Cherokee group under General Andrew Jackson. After a conflict called the Red Stick War, Ross started a tobacco farm in Tennessee. In 1816, he built a warehouse and trading post on the Tennessee River. He also started a ferry service. These businesses became the start of a community called Ross's Landing, which is now Chattanooga, Tennessee. At the same time, Ross became very interested in Cherokee politics. Important Cherokee leaders like Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks became his mentors.

In 1816, Ross went to Washington, D.C., with other Cherokee leaders. They talked about land borders and white settlers moving onto Cherokee land. Ross was the only one who spoke fluent English, so he became the main negotiator. When he returned in 1817, he was elected to the National Council. The next year, he became the council president. Most council members were like Ross: wealthy, educated, and English-speaking. Even traditional Cherokee people saw that he had the skills to protect their land. Ross immediately refused an offer of $200,000 from the US government to make the Cherokee move. He made more trips to Washington as demands for Cherokee land grew. In 1824, Ross bravely asked the US Congress for help. This was the first time a Native American tribe had done this. Ross gained support for the Cherokee cause in Washington.

In January 1827, both Principal Chief Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks died. William Hicks, Charles's brother, became interim chief. Ross and Major Ridge shared responsibilities for the tribe. William Hicks was not seen as a strong leader. So, in October 1828, the Cherokee elected John Ross as their permanent Principal Chief. He held this position until he died.

The idea of moving the Cherokee Nation caused a big split. Ross, supported by most of the people, tried to stop the US government from forcing them to move. His group was called the National Party. Another group, the "Treaty Party" or "Ridge Party," believed they could not resist. They wanted to get the best deal possible. This group was led by Major Ridge. The Treaty Party signed the Treaty of New Echota on December 29, 1835. This treaty said the Cherokee had to leave by 1838. Chief Ross and the National Council never approved this treaty. But the US government said it was valid. Ross and thousands of traditional Cherokee people refused to follow this unfair treaty.

To force the treaty, the US Army moved those who did not leave by 1838. They gathered people from many villages and towns and made them walk west. This forced journey is known as the "Trail of Tears." It was called this because of the sadness of losing their homeland and the thousands of lives lost. About one-fourth of the Cherokee who were forced to move died along the trail. Ross's wife, Quatie, was one of them. Some Cherokee hid in the wilderness to avoid the army. Their descendants became the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Ross tried to bring his people back together after they reached Indian Territory. But opponents of the forced move killed the leaders of the Treaty Party. Stand Watie escaped and became Ross's biggest enemy. The issue of slavery soon caused more divisions. The Treaty Party became the "Southern Party." Ross's National Party largely became the "Union Party." Ross first wanted the Cherokee to stay neutral in the American Civil War. He thought joining the "white man's war" would hurt the tribe's unity.

When Union forces left their forts in Indian Territory, Ross changed his mind. He signed a treaty with the Confederacy. But he later fled to Union-held Kansas. Stand Watie then became the main chief. The Confederates lost the war, and Watie was the last Confederate general to surrender. Ross then returned to his post as Principal Chief.

After the war, the US government required the Five Civilized Tribes to make new peace treaties. Ross traveled to Washington, D.C., for this reason. He died there on August 1, 1866.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Ross, also known by his Cherokee name Guwisguwi, was born in Turkeytown (in modern-day Alabama). His mother was Mollie McDonald, and his father was Daniel Ross, a Scottish trader. John had several brothers and sisters.

Family Background

The Cherokee kinship system is matrilineal. This means children belong to their mother's family and clan. John Ross and his siblings were part of his mother's Bird Clan. They gained their social standing from her family. In this system, the mother's oldest brother often played a big role in the children's lives. Ross's mother and grandmother were of mixed race. But they were raised mainly in Cherokee culture.

Ross's great-grandmother, Ghigooie, was a full-blood Cherokee. She married William Shorey, a Scottish interpreter. Their daughter, Anna, married John McDonald, another Scottish trader. John McDonald was John Ross's grandfather.

Growing Up and School

Ross grew up near Lookout Mountain. He was educated in English by white teachers. He did not speak the Cherokee language very well. But his mixed background and fluency in English helped him represent the Cherokee to the US government. Many full-blood Cherokee visited his father's trading company. So, he met many tribal members. As a child, Ross took part in tribal events, like the Green Corn Festival.

John's father wanted him to have a good education. After being taught at home, Ross went to schools run by Reverend Gideon Blackburn. These schools were in southeast Tennessee for Cherokee children. Classes were in English, and most students were of mixed race, like Ross. He finished his education at an academy near Kingston, Tennessee.

Mixed Heritage Leaders

Ross's life was similar to other important mixed-race leaders in North America. Scottish and English fur traders often married high-ranking Native American women. Both sides saw these marriages as good for their communities. Their children were raised in cultures that blended both traditions. These mixed-race children often became important leaders in their societies.

Family Life

John Ross had two wives and several children. He married Elizabeth "Quatie" (Brown) Henley, a Cherokee woman, around 1812. She had one child from a previous marriage. Quatie Ross died in 1839 in Arkansas during the Trail of Tears. She had several children with John Ross.

John Ross married again in 1844 to Mary Stapler. She died in 1865, less than a year before him. They had two children together.

Careers and Leadership

Indian Agent and Businessman

At age twenty, Ross became a US Indian agent for the western Cherokee in Arkansas Territory. During the War of 1812, he served in a Cherokee group. He fought under General Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.

Ross started several businesses that made him very wealthy. He grew a lot of tobacco in Tennessee. He had about 20 enslaved African Americans to help with this labor-intensive crop.

In 1816, he founded Ross's Landing, which had a ferry crossing. After the Cherokee were forced to move, white settlers changed the name of Ross's Landing to Chattanooga. Ross also had a trading company and warehouse. He earned a lot of money from these businesses.

Many Cherokee moved to northeast Georgia because of pressure from white settlers. In 1827, Ross moved to Rome, Georgia, closer to New Echota, the Cherokee capital. In Rome, Ross started another ferry service. By 1836, Ross was one of the five wealthiest men in the Cherokee Nation.

Learning to Lead

From 1811 to 1827, Ross learned how to negotiate with the United States. He also gained skills to run a national government. Older chiefs like Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks supported his political career. They saw that Ross, with his education and English skills, could best defend Cherokee interests. Ross served as their clerk and worked on all financial and political matters. They also taught him about Cherokee traditions.

In 1816, the chiefs' council sent Ross on his first trip to Washington D.C. The group had to deal with important issues like land borders and white settlers moving onto Cherokee land. Ross's fluency in English made him a key figure.

In November 1817, the Cherokee formed the National Council. Ross was elected to this thirteen-member group. The Council was created to strengthen Cherokee political power. This was after General Andrew Jackson made treaties with small groups of Cherokee who did not represent the whole nation. Being on the National Council placed Ross among the Cherokee's top leaders. Most members were wealthy, of mixed heritage, and spoke English.

President of the National Committee

In November 1818, Ross became president of the National Committee. He held this position until 1827. The Council chose Ross because they believed he had the diplomatic skills to refuse American demands for Cherokee lands. He quickly turned down an offer of $200,000 from the US government. This money was offered if the Cherokee would move west of the Mississippi.

In 1819, Ross went to Washington again with a Cherokee group. He took on a bigger leadership role. They wanted to make the Treaty of 1817 clearer. They wanted to limit the land given up and protect the Cherokee's right to their remaining lands. The US Secretary of War, John C. Calhoun, pushed Ross to give up large areas of land in Tennessee and Georgia. Ross refused. But the US government kept up the pressure. In October 1822, Calhoun asked the Cherokee to give up land claimed by Georgia. Ross first asked the Cherokee people what they thought. They all said no to giving up more land.

In January 1824, Ross traveled to Washington to defend the Cherokee's land. Calhoun offered two choices: give up their lands and move west, or become US citizens. Ross refused Calhoun's offer. Instead, he directly asked Congress for help on April 15, 1824. This was a new approach for a Native American nation.

No Indian nation had ever before asked Congress for help with their problems. Ross's letters changed from a submissive tone to one of strong defense. He argued complex legal points.

Some politicians in Washington noticed this change in leadership. Future president John Quincy Adams said Ross's speeches sounded more like "white discourse" than traditional Indian speeches. Adams called Ross "the writer of the delegation." He noted that they "sustained a written controversy against the Georgia delegation with great advantage." Even Georgia's delegation admitted Ross's skill. An article in The Georgia Journal said the Cherokee letters were "too refined to have been written or dictated by an Indian."

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

In January 1827, both Principal Chief Pathkiller and Charles R. Hicks, Ross's mentor, died. Ross, as president of the National Committee, and Major Ridge, as speaker of the National Council, were in charge of the tribe's affairs. William Hicks, Charles's brother, was interim chief for a short time. But he did not impress the tribe. Most people knew that Ross had handled the tribe's business. On October 17, 1828, the Cherokee elected John Ross as Principal Chief.

Throughout the 1820s, the Cherokee Council created a new national government. It had two parts, like the US government. In 1822, they created the Cherokee Supreme Court. In May 1827, Ross was elected to the committee that wrote a constitution. This constitution created a Principal Chief, a council, and a National Committee. Together, these would form the General Council of the Cherokee Nation, a constitutional republic. The constitution was approved in October 1827. It took effect in October 1828, when Ross was elected Principal Chief. He was reelected many times and stayed in this job until he died in 1866. He was very popular with both full-blood Cherokee and mixed-blood Cherokee.

The Cherokee had built a government that could make clear plans to protect their rights.

Supreme Court Cases

Ross found support in Congress from people like senators Henry Clay and Daniel Webster. But in April 1829, John H. Eaton, the Secretary of War, told Ross that President Jackson would support Georgia's right to control the Cherokee people.

On December 8, 1829, President Andrew Jackson announced he wanted Congress to pass a bill. This bill would require Indian tribes in the Southeast to move west of the Mississippi River.

On December 19, 1829, Georgia passed laws that greatly limited the Cherokee Nation. They took a large part of Cherokee land. They said Cherokee law was not valid in that area. They banned Cherokee government meetings in Georgia. They made contracts between Indians and whites invalid unless two white people witnessed them. They did not allow Indians to testify against white people in court. And they forbade Cherokee from digging for gold on their own lands. These laws were meant to force the Cherokee to move.

In May 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. President Jackson signed it on May 23. This law allowed the president to exchange lands west of the Mississippi for the lands of Indian nations in the Southeast. In the summer of 1830, Jackson urged the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek to sign treaties agreeing to move. The Cherokee refused to meet with Jackson. The other tribes signed.

When Ross and the Cherokee leaders failed to protect their lands through the government, Ross decided to defend Cherokee rights in the US courts. In June 1830, the Cherokee leaders chose William Wirt, a former US Attorney General, to defend their rights before the US Supreme Court.

Wirt argued two cases for the Cherokee: Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Court did not rule in favor of the Cherokee. The Court said it did not have the power to hear a case where a tribe was a party.

In 1832, the Supreme Court further explained the relationship between the federal government and the Cherokee Nation. In Worcester v. Georgia, the Court said that Georgia could not extend its laws to the Cherokee Nation. This power belonged to the federal government. The Cherokee were seen as sovereign enough to legally resist Georgia's government. But the issue became complicated when the Indian Removal Act gave the federal government the legal power to handle the whole situation. These court decisions made Jackson look bad politically.

Meanwhile, the Cherokee Nation faced financial problems. The US government stopped paying them money for previous land deals. Georgia stopped any income from gold on Cherokee lands. And the Cherokee Nation's request for a federal loan was denied. Ross struggled to pay the Cherokee Nation's legal bills.

Opposition from the Ridge Party

In May 1832, Supreme Court Justice John McLean met with the Cherokee leaders. He suggested they "remove and become a Territory." He said they would get land in the west and a representative in Congress. Ross was very angry, thinking this was a betrayal.

McLean's advice caused a split among Cherokee leaders. John Ridge and Elias Boudinot began to doubt Ross's leadership. John Ridge suggested sending a group to Washington to discuss a removal treaty with President Jackson. The council rejected Ridge's idea. Instead, they chose Ross and others to represent the Cherokee. In February 1833, Ridge wrote to Ross, saying the group sent to Washington should start talks about moving. Ridge and Ross both knew the Cherokee could not stop Georgia from taking their land. But Ridge was angry that Ross had refused Jackson's offer of $3 million for all their lands.

In this situation, Ross led a group to Washington in March 1834. He tried to negotiate other options besides removal. Ross made several proposals. But the Cherokee Nation might not have approved them. And Jackson was unlikely to agree to anything less than removal. These offers, and the long trips, showed that Ross wanted to delay the talks about moving. He hoped the next President might be more favorable.

Ross's plan had a weakness: the US could make a treaty with a small group of Cherokee. On May 29, 1834, Ross learned that a new group, including Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and Ross's younger brother Andrew, had arrived in Washington. This group was called the "Ridge Party" or "Treaty Party." Their goal was to sign a removal treaty. The two sides tried to make peace, but by October 1834, they still had no agreement. In January 1835, the groups were in Washington again. Under pressure from the Ridge Party, Ross agreed on February 25, 1835, to exchange all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi for land west of it. He asked for $20 million. But he said the General Council had to approve the terms.

Treaty of New Echota and the Trail of Tears

Secretary of War Lewis Cass thought Ross was just trying to delay things again. He threatened to sign the treaty with John Ridge. On November 7, 1835, Ross and his guest, John Howard Payne, were arrested by the Georgia guard at Ross's home. They were taken to Spring Place, Georgia, and put in prison. On December 29, 1835, the Treaty Party signed the Treaty of New Echota with the U.S. Most Cherokee believed the people who signed it did not have the authority to do so. But Ross could not stop it from being enforced. President Martin Van Buren ordered General Winfield Scott and 7,000 Federal troops to force the Cherokee to move if they did not leave by 1838. This forced move became known as the Trail of Tears. Accepting defeat, Ross convinced General Scott to let him oversee much of the removal process.

Returning home late one night, Ross saw a man he didn't know at his house. The man told Ross he now owned the property and had papers to prove it. Ross learned that Georgia agents had given the house to this man after evicting his family. Ross was now homeless. The next day, he found that family members had given his wife Quatie a place to stay. Quatie died of pneumonia on February 1, 1839, on a steamboat on the Arkansas River. She was buried in Little Rock.

Selling common lands was a serious crime under Cherokee law. So, after the move to Indian Territory, people who opposed the treaty killed Boudinot, Major Ridge, and John Ridge. Stand Watie, Boudinot's brother, was also attacked but survived. The killers were never publicly identified or tried. Some Cherokee believed Chief John Ross knew about the killings beforehand. But Ross's son, Allen, later wrote that this was not true. After this, there were years of violence between the two groups.

Because of the land struggle and Ross's wealth, some Cherokee and US leaders thought Ross was a dictator. But Ross also had powerful supporters in Washington. Thomas L. McKenney, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, called Ross the "father of the Cherokee Nation." He said Ross was like Moses, leading his people from their homeland to a new country.

Remarriage

John Ross met the Stapler family in Brandywine Springs, Delaware, in 1841. Ross had many things in common with John Stapler, a merchant. Stapler's younger daughter, Mary Brian Stapler, fell in love with Ross. They married in Philadelphia on September 2, 1844.

American Civil War and Later Life

The American Civil War divided the Cherokee people. At first, most supported the Confederacy. This was because the Confederacy protected their right to own enslaved people. Ross tried to convince his people to stay neutral. He feared joining the war would cancel earlier treaties with the United States. But eventually, most Cherokee chose sides. Full-blood Cherokee often favored staying with the United States. This group included over two thousand members of the Keetoowah Society, who opposed slavery.

Ross argued for the Cherokee Nation to remain neutral. But it was a losing argument. On August 21, 1861, Ross announced that the Cherokee should ally with the Confederate States of America. Many wealthy mixed-blood Cherokee, led by Stand Watie, supported the Confederacy. Traditionalists and Cherokee who opposed slavery remained loyal to the Union. However, many Cherokee may not have fully understood the new treaty.

After Ross left to meet with President Lincoln, traditional Cherokee helped choose Thomas Pegg as Acting Principal Chief. Three or four of Ross's own sons fought for the Union. But Ross's nephew by marriage, John Drew, led a Confederate Cherokee regiment. Most of Drew's regiment later refused to follow Confederate orders to kill other Indians. Many leaders of the pro-Union group, still led by Ross, went to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, for the war.

By 1863, many Cherokee voters had fled to Kansas and Texas. This gave the pro-Confederate Treaty Party a chance to elect Stand Watie as Principal Chief without them. Pro-Union National Council members said the election was invalid. That fall, Watie's men raided Ross's home, Rose Cottage. The home was looted and burned. Ross lost all his belongings. Ross's daughter Jane and her husband, Andrew Nave, were living there. Nave was shot and killed. Ross's oldest son, James, was captured and died in a Confederate prison. Ross remained in exile. But within a week of the burning, the National Council met and restored Ross as Principal Chief.

Ross took his wife Mary and children to Philadelphia to see her family. Ross returned to Washington for a meeting with President Lincoln. When he came back for Mary in 1865, she was very ill. She died on July 20, 1865, and was buried in Delaware. Ross returned to Indian Territory after her funeral.

After the war, the two Cherokee groups tried to negotiate separately with the US government. The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Dennis N. Cooley, was convinced by Stand Watie and Elias Cornelius Boudinot that Ross was a dictator. Even though his health was getting worse, Ross left Park Hill on November 9, 1865, to meet with President Andrew Johnson. Johnson told Cooley to restart talks with the Cherokee and to meet only with the pro-Union group, led by John Ross. Ross died on August 1, 1866, in Washington, D.C., while still negotiating a final treaty. However, Ross had convinced Johnson to reject a very harsh treaty version that Cooley favored.

Death and Legacy

Ross was first buried next to his second wife Mary in Wilmington and Brandywine Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware. A few months later, the Cherokee Nation moved his remains to the Ross Cemetery at Park Hill, Indian Territory (now Cherokee County, Oklahoma).

John Ross's great-great granddaughter, Mary G. Ross (1908–2008), was the first Native American female engineer. She helped with space travel and became a famous woman scientist of the space age.

Honors and Monuments

The city of Chattanooga named the Market Street Bridge after Ross. A statue of Ross stands on the lawn of the Hamilton County Courthouse.

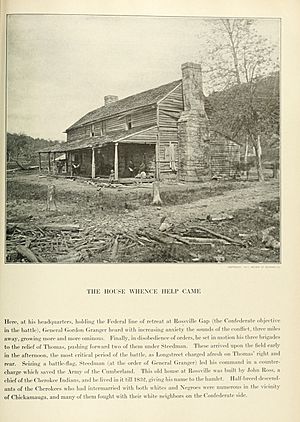

The city of Rossville, Georgia, is named for Ross. It has his former home, the John Ross House. He lived there from 1830 to 1838 until the state took his lands. It is one of the oldest homes in the Chattanooga area and is a National Historic Landmark.

The city of Park Hill, Oklahoma, has a John Ross museum in an old schoolhouse near Ross Cemetery.

National Public Radio correspondent Steve Inskeep suggested that the US $20 bill should show images of both John Ross and Andrew Jackson. This would show different parts of American history.

Media Portrayals

- John Ross was played by Johnny Cash in a TV episode called "Trail of Tears" in 1971.

- John Ross's life and the Trail of Tears are shown in Episode 3 of the Ric Burns documentary, We Shall Remain (2009), on PBS.

See also

In Spanish: John Ross para niños

In Spanish: John Ross para niños

- Timeline of Cherokee removal

- Indian Removal Act

- List of treaties of the Confederate States of America

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |