Winfield Scott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Winfield Scott

|

|

|---|---|

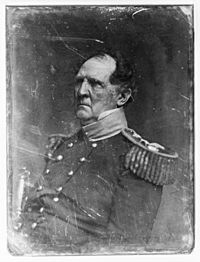

Scott photographed in 1862

|

|

| Commanding General of the U.S. Army | |

| In office July 5, 1841 – November 1, 1861 |

|

| President | |

| Preceded by | Alexander Macomb |

| Succeeded by | George B. McClellan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 13, 1786 Dinwiddie County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | May 29, 1866 (aged 79) West Point, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | West Point Cemetery, West Point, New York |

| Political party | Whig |

| Education | College of William and Mary |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal (2) |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Virginia Militia United States Army |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Major General Brevet Lieutenant General |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

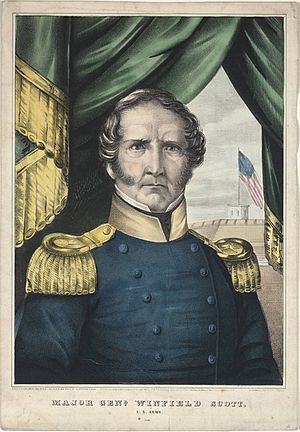

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786 – May 29, 1866) was an important American military leader and political figure. He served as a general in the United States Army for many years, from 1814 to 1861. He fought in several major conflicts, including the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, and the early parts of the American Civil War. He also took part in conflicts with Native American tribes.

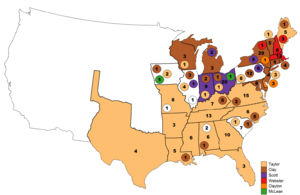

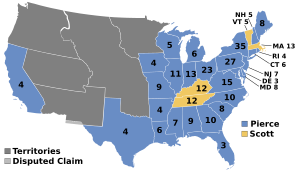

Scott was the Whig Party's choice for president in the 1852 election. However, he lost to Democrat Franklin Pierce. People knew him as Old Fuss and Feathers because he always insisted on proper military rules and manners. He was also called the Grand Old Man of the Army because he served for so many years.

Scott was born in Virginia in 1786. He studied to become a lawyer and had a short time in the local militia. In 1808, he joined the army as a captain. During the War of 1812, he fought in Canada, including the Battle of Queenston Heights and the Battle of Fort George. He became a brigadier general in 1814. He fought bravely at the Battle of Chippawa but was badly hurt at the Battle of Lundy's Lane.

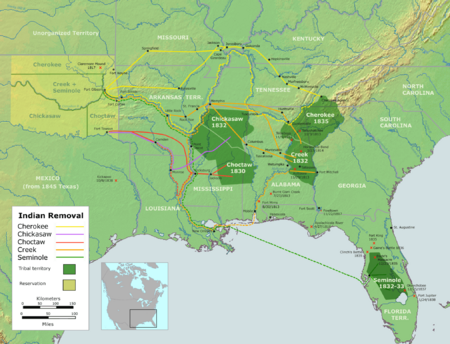

After the war, Scott commanded army forces in the Northeastern United States. In the 1830s, he helped end the Black Hawk War. He also took part in the Second Seminole War and the Creek War of 1836. Scott oversaw the difficult forced relocation of the Cherokee people. He also helped avoid war with Britain by calming tensions during the Patriot War and the Aroostook War.

In 1841, Scott became the Commanding General of the United States Army. When the Mexican–American War started in 1846, he led a campaign against the Mexican capital, Mexico City. He captured the port city of Veracruz. Then, he defeated Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna's armies in battles like Cerro Gordo and Churubusco. He successfully captured Mexico City. After this, he helped keep order and supported the negotiation of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war.

Scott tried three times to become the Whig presidential candidate, in 1840, 1844, and 1848, but did not succeed. He finally won the nomination in 1852. However, the Whig Party was already struggling. Franklin Pierce won the election easily. Despite this, Scott remained popular. In 1855, he became a brevet lieutenant general. He was the first U.S. Army officer to hold this rank since George Washington. In 1859, he peacefully resolved the Pig War, which was the last border conflict between Britain and America.

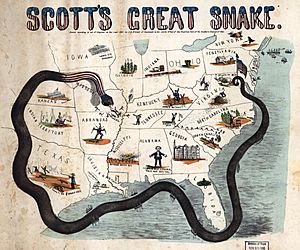

Even though he was from Virginia, Scott stayed loyal to the Union when the Civil War began. He advised President Abraham Lincoln in the early stages of the war. He created a plan called the Anaconda Plan. He retired in late 1861 as Lincoln started to rely more on General George B. McClellan. Scott lived in West Point, New York, after retiring. He died there on May 29, 1866. Many people thought Scott was a very skilled general. Historians consider him one of the most successful generals in U.S. history.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Winfield Scott was born on June 13, 1786. He was the fifth child of Ann Mason and William Scott. His father was a farmer, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, and an officer in the local militia. The Scott family lived on a farm called Laurel Hill, near Petersburg, Virginia. Scott's first name, Winfield, came from his maternal grandmother's family name.

Scott's paternal grandfather, James Scott, came from Scotland. He moved to America after a battle in Scotland. Scott's father died when Winfield was six years old. His mother raised him and his siblings. Even though his family was wealthy, most of the family's money went to his older brother, James, who inherited the farm. Scott was a very tall and strong man, standing six feet, five inches tall and weighing 230 pounds.

Scott went to schools run by James Hargrave and James Ogilvie. In 1805, he started attending the College of William and Mary. But he soon left to study law with a lawyer named David Robinson. During this time, Scott attended the trial of Aaron Burr, who was accused of treason. Scott developed a negative opinion of General James Wilkinson, who was the senior army officer at the time. Wilkinson seemed to try to hide his involvement in Burr's actions.

Scott became a lawyer in 1806 and practiced law in Virginia. In 1807, he got his first military experience as a corporal in the Virginia Militia. This was during the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, a naval dispute with Britain. Scott led a small group that captured British sailors. However, Virginia authorities did not approve and released the prisoners. Later that year, Scott tried to practice law in South Carolina but couldn't get a license because he hadn't lived there long enough.

Joining the Army and Early Challenges

First Years in the Army

In early 1808, President Thomas Jefferson asked Congress to make the United States Army bigger. This was because Britain was threatening American ships. Scott convinced a family friend to help him get a position in the army. In May 1808, just before his 22nd birthday, Scott became a captain in the light artillery. He recruited his company from Virginia and then traveled with them to New Orleans. Scott was upset by how unprofessional the army seemed at the time. It had only about 2,700 officers and men.

Scott soon had problems with his commander, General James Wilkinson. Wilkinson refused to move troops from an unhealthy camp, even though the Secretary of War ordered it. Wilkinson owned the land and made money from the soldiers staying there. This caused many soldiers to get sick and even die.

Scott briefly left the army because he was unhappy with Wilkinson. But he changed his mind and returned. In January 1810, Scott faced a military trial. This was partly because he made disrespectful comments about Wilkinson. It was also because of a small amount of money missing from funds he was given for recruiting. The court decided Scott wasn't dishonest but had not kept good records. His army position was suspended for one year. After the trial, Scott fought a duel with an army medical officer who he blamed for the trial. Both were unharmed.

Scott returned to Virginia and spent the year studying military tactics and law. Wilkinson was later removed from command. Scott rejoined the army, and his peers welcomed him. This made him believe that most officers agreed with his views on Wilkinson.

Fighting in the War of 1812

Tensions grew between Britain and the United States. Britain attacked American ships and forced American sailors into their navy. They also encouraged Native American resistance to American settlers. In July 1812, Congress declared war on Britain. Scott was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He was assigned to the 2nd Artillery.

Scott led two companies north to join General Stephen Van Rensselaer's militia. This force was preparing to invade Canada. President James Madison wanted to capture Montreal to control the St. Lawrence River. The invasion would start with an attack on Queenston, Ontario.

In October 1812, Van Rensselaer's forces attacked British forces in the Battle of Queenston Heights. Scott led an artillery attack that helped American troops cross the Niagara River. He took command of American forces at Queenston after another officer was badly wounded. Soon after, a larger British force arrived. Scott had to surrender because more American militia did not arrive. As a prisoner of war, Scott was treated well by the British. He was released in November as part of a prisoner exchange.

When he returned to the U.S., Scott was promoted to colonel. He was given command of the 2nd Artillery. He also became chief of staff to General Henry Dearborn, who led operations against Canada.

Dearborn ordered Scott to lead an attack on Fort George. This fort was important on the Niagara River. With help from naval commanders, Scott landed American forces behind the fort, forcing it to surrender. Scott was praised for his actions. In November 1813, Scott forced the British to retreat from Hoople Creek. However, the campaign to capture Montreal failed. President Madison replaced Wilkinson and other senior officers with younger ones like Scott. In early 1814, Scott became a brigadier general.

In mid-1814, Scott took part in another invasion of Canada. Scott was key to the American victory at the Battle of Chippawa on July 5, 1814. This battle was important because it was the first time American troops truly defeated British regular soldiers.

Later in July 1814, Scott's scouting group was ambushed. This started the Battle of Lundy's Lane. Scott's brigade suffered heavy losses. He was badly wounded while trying to commit his reserve forces. Scott believed that the general's decision not to fully commit troops early on led to many unnecessary deaths. The battle ended without a clear winner. Scott spent months recovering from his wounds.

Scott's performance at Chippawa earned him national fame. He was promoted to the brevet rank of major general. He also received a Congressional Gold Medal. In October 1814, Scott commanded American forces in Maryland and northern Virginia. The War of 1812 ended in February 1815 after news of the Treaty of Ghent arrived.

In 1815, Scott became an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati. This was to recognize his service in the War of 1812. His special Society of the Cincinnati medal was a unique, solid gold eagle. It is now in the United States Military Academy Museum.

Family Life

In March 1817, Scott married Maria DeHart Mayo. She was the daughter of a wealthy engineer and businessman from a well-known Virginia family. Scott and his family lived in Elizabethtown, New Jersey for about 30 years. From the late 1830s, Maria spent much time in Europe due to a lung condition. She died in Rome in 1862. They had seven children, five daughters and two sons:

- Maria Mayo Scott (1818–1833), who died as a teenager.

- John Mayo Scott (1819–1820), who died young.

- Virginia Scott (1821–1845), who became a nun.

- Edward Winfield Scott (1823–1827), who died young.

- Cornelia Winfield Scott (1825–1885), who married Colonel Henry Lee Scott. He was Winfield Scott's aide.

- Adeline Camilla Scott (1831–1882), who married a New York City businessman.

- Marcella Scott (1834–1909), who married Charles Carroll MacTavish.

Mid-Career and Important Roles

Post-War Years and "Old Fuss and Feathers"

After the War of 1812, Scott helped decide which officers would stay in the army. Andrew Jackson and Brown became the two major generals. Scott and three others became brigadier generals. Scott took time off to study warfare in Europe. When he returned in May 1816, he commanded army forces in the Northeastern United States. He set up his headquarters in New York City.

He earned the nickname "Old Fuss and Feathers." This was because he always insisted on proper military behavior, courtesy, appearance, and discipline. In 1835, Scott wrote a three-volume book called Infantry Tactics. This book was the standard drill manual for the U.S. Army until 1855.

Scott had a rivalry with Andrew Jackson for a while, but they later became friends. He also had a long-standing feud with General Gaines over who was senior. Both hoped to replace the ailing General Brown. When Brown died in 1828, President John Quincy Adams chose Macomb instead of Scott or Gaines because of their feuding. Scott was very angry and threatened to resign, but he eventually stayed in the army.

Black Hawk War and Nullification Crisis

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson ordered Scott to Illinois. He was to take command in the Black Hawk War. By the time Scott arrived, the war had ended. Scott and Governor John Reynolds signed a treaty with Chief Keokuk and other Native American leaders. This treaty opened up much of present-day Iowa for white settlement.

Later in 1832, Jackson put Scott in charge of army preparations for a possible conflict during the Nullification Crisis. Scott went to Charleston, South Carolina, where the crisis was centered. He strengthened federal forts there. He also tried to convince people not to support leaving the Union. The crisis ended peacefully in early 1833.

Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

President Jackson started a policy of Indian removal. This meant forcibly moving Native Americans to lands west of the Mississippi River. Some Native Americans moved peacefully, but others, like many Seminoles, fought back. In December 1835, the Second Seminole War began after the Dade massacre. In this event, Seminoles attacked and killed a U.S. Army company in Florida.

President Jackson ordered Scott to take command against the Seminole. Scott arrived in Florida in February 1836. After several months of fighting without a clear victory, he was ordered to Alabama and Georgia. He was to stop a Muscogee uprising called the Creek War of 1836. American forces quickly defeated the Muscogee. Scott's actions in these campaigns received some criticism. A court investigated Scott and Gaines. The court cleared Scott of wrongdoing but criticized his language when criticizing Gaines.

Martin Van Buren became president in 1837. He continued Jackson's policy of Indian removal. In April 1838, Van Buren put Scott in command of removing the Cherokee from the Southeastern United States. Some of Scott's friends tried to stop him from taking this command, as they saw it as wrong. But Scott accepted his orders.

Most Cherokee refused to move willingly. Scott made careful plans to ensure his soldiers moved them by force, but as humanely as possible. However, the Cherokee still suffered abuse from soldiers. One account said soldiers drove them "like cattle, through rivers." In mid-1838, Scott agreed to Chief John Ross's plan to let the Cherokee lead their own move west. Scott was criticized by many Southerners for this decision. Scott observed one Cherokee group's journey.

Avoiding War with the United Kingdom

In late 1837, the "Patriot War" started along the Canadian border. Some Americans tried to support rebellions in Canada. Tensions grew even more after the Caroline affair. In this event, Canadian forces burned a steamboat used to supply rebels. President Van Buren sent Scott to Western New York to prevent more border crossings and avoid war with Britain. Scott was still popular from the War of 1812. He asked Americans not to support the Canadian rebels.

In late 1838, a new crisis called the Aroostook War began. This was about a border dispute between Maine and Canada that had not been settled. Scott was tasked with preventing this conflict from becoming a full war. He gained the support of Maine's governor. Scott then negotiated a truce with the British commander in the area.

Presidential Election of 1840

In the mid-1830s, Scott joined the Whig Party. This party was formed by people who opposed President Jackson. Scott's success in preventing war with Canada made him popular. In early 1839, newspapers started mentioning him as a possible presidential candidate. By the time of the convention in December 1839, Henry Clay and William Henry Harrison were the main candidates. Scott was seen as a possible compromise candidate if they couldn't agree. After many votes, the convention nominated Harrison for president.

Harrison won the 1840 presidential election against Van Buren. However, Harrison died just one month into his term. Vice President John Tyler became president.

Commanding General of the U.S. Army

Service Under President Tyler

On June 25, 1841, Macomb died. Scott and Gaines were the two most likely choices for Commanding General of the United States Army. The Secretary of War recommended Scott, and President Tyler approved. Scott was also promoted to major general. Before Scott, the commanding general had little control over the army staff. Their advice was also rarely sought by civilian leaders.

Scott tried to make the office more important. However, he had little influence with President Tyler. Tyler quickly became unpopular with most of the Whig Party. Some Whigs wanted Scott to be their candidate in the 1844 presidential election. But Clay quickly became the clear favorite for the Whig nomination. Clay won the nomination but lost the election to Democrat James K. Polk. Polk's campaign focused on adding Texas to the U.S. After Polk won, Congress approved the annexation of Texas. Texas became a state in 1845.

Mexican–American War

Early War and Invasion Plan

Polk and Scott did not like each other. Their distrust grew after Polk became president, partly because Scott was a Whig. Polk had two main goals: to get Oregon Country and to get Alta California from Mexico. The U.S. almost went to war with Britain over Oregon. But they agreed to divide Oregon Country.

The Mexican–American War started in April 1846. U.S. forces under General Zachary Taylor fought Mexican forces near the Rio Grande. This area was claimed by both Mexico and Texas. Polk, the Secretary of War, and Scott agreed on a plan. The U.S. would capture Northern Mexico and then seek a peace deal. While Taylor led the army in Northern Mexico, Scott oversaw the army's growth. He made sure new soldiers had supplies and were organized.

Capturing Mexico City

Taylor won several battles. But Polk decided that just holding Northern Mexico wouldn't make Mexico surrender. Scott created an invasion plan. It would start with a naval attack on the port of Veracruz and end with capturing Mexico City. Polk reluctantly chose Scott to command the invasion. Many officers who later became famous in the American Civil War joined this campaign. These included Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant.

Scott's invasion of Mexico through Veracruz was a huge operation. It began on March 9, 1847, with the Siege of Veracruz. Scott's army of 12,000 men landed safely. They surrounded Veracruz and began attacking it. The Mexican forces surrendered on March 27. Scott wanted to gain the cooperation of the Catholic Church. He ordered his men to respect church property and salute Catholic priests.

After getting supplies, Scott's army marched towards Xalapa, on the way to Mexico City. Meanwhile, Polk sent Nicholas Trist to negotiate a peace treaty. Scott and Trist, though they first argued, later worked well together.

In mid-April, Scott's army met Santa Anna's army at Cerro Gordo. Santa Anna had a strong defensive position. But he left his left side unprotected, thinking the dense trees made it impassable. Scott attacked from two sides. One force attacked Santa Anna's left side. Another attacked his artillery. In the Battle of Cerro Gordo, the American forces captured a key Mexican position. Mexican resistance collapsed. Santa Anna escaped, but Scott's army captured about 3,000 Mexican soldiers. Scott continued towards Mexico City, cutting off his supply lines.

Scott's army reached the Valley of Mexico in August 1847. Santa Anna had gathered about 25,000 men. Mexico City had no walls, so Santa Anna wanted to defeat Scott in a major battle. He chose to defend near the Churubusco River, south of the city. The Battle of Contreras began on August 19. An American force surprised and defeated Valencia's army. This defeat caused panic among Santa Anna's troops. Scott immediately attacked, starting the Battle of Churubusco. Scott's forces quickly defeated the Mexican army.

After the battle, Santa Anna negotiated a truce with Scott. The Mexican foreign minister told Trist they were ready to talk peace. Despite Scott's army being outside Mexico City, the two sides disagreed on terms. Mexico only wanted to give up parts of California and refused to accept the Rio Grande as its border.

During negotiations, Scott dealt with 72 members of the Saint Patrick's Battalion. These were soldiers who had left the U.S. Army and fought for Mexico. All 72 were tried by a military court and sentenced to death. Scott spared 20 of them, but the rest were executed. In early September, peace talks broke down. Scott ended the truce. In the Battle for Mexico City, Scott attacked from the west. He captured the important fortress of Chapultepec on September 13. Santa Anna retreated, and Scott accepted the surrender of the remaining Mexican forces on September 14.

After capturing Mexico City, Scott and the army restored order with the help of local leaders and the Catholic Church. Peace talks between Trist and the Mexican government started again. Scott supported these talks and stopped all further attacks. Scott was highly respected for how fairly he treated Mexican citizens. In November 1847, Trist was ordered back to Washington, and Scott was ordered to continue the military campaign. Polk was frustrated with the slow pace of talks. With Scott's support, Trist ignored his orders and continued negotiations.

Trist and the Mexican negotiators signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. The U.S. Senate approved it the next month. In late 1847, Scott arrested some officers who criticized him in newspapers. In response, Polk ordered their release and removed Scott from command.

Scott was elected an honorary member of the Aztec Club of 1847. This was a military society for officers who served in Mexico during the war.

Presidential Elections and Later Service

Scott was again considered for the Whig presidential nomination in the 1848 election. Other candidates included Henry Clay and General Zachary Taylor. Whigs were looking for a war hero who wasn't too focused on politics. Scott appealed to anti-slavery Whigs. They were upset that Clay and Taylor owned slaves. However, the delegates chose Taylor as their candidate. Many anti-slavery Whigs then supported former President Martin Van Buren. Taylor went on to win the election.

After the war, Scott returned to his duties as the army's senior general. Congress debated the issue of slavery in new territories. Scott supported the Compromise of 1850. This was a series of laws meant to settle the slavery question. Meanwhile, Taylor died in July 1850. Vice President Millard Fillmore became president. The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 deeply divided the country and the Whig Party. Northerners strongly disliked the strict rules of the Fugitive Slave Act. Southerners complained if it wasn't enforced enough.

Presidential Election of 1852

By early 1852, Scott was a leading candidate for the Whig presidential nomination. He was supported by Northern Whigs who opposed the Compromise. President Fillmore was favored by most Southern Whigs. The 1852 Whig National Convention began on June 16. Southern delegates passed a party platform that supported the Compromise of 1850.

After many votes, Scott finally won the nomination on the 53rd ballot. Fillmore accepted his defeat and supported Scott. However, many Northern Whigs were upset when Scott publicly supported the party's pro-Compromise platform. Many Southern Whigs refused to support Scott.

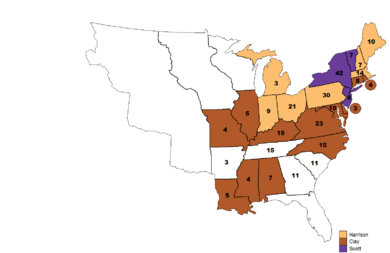

The 1852 Democratic National Convention nominated Franklin Pierce. He was a Northerner who sympathized with the Southern view on slavery. Pierce had served under Scott in the Mexican War. Democrats attacked Scott for various past incidents, including his court-martial in 1809. Scott was not a very popular candidate. He suffered the worst defeat in Whig history. Scott won only four states and 44 percent of the popular vote. Pierce won almost 51 percent of the popular vote and a large majority of the electoral votes.

Pierce and Buchanan Administrations

After the 1852 election, Scott continued as the army's senior officer. He got along well with President Pierce. But he often argued with Pierce's Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis. Despite his election loss, Scott remained popular. In 1855, Congress promoted Scott to brevet lieutenant general. He was the first U.S. Army officer since George Washington to hold this rank. He also earned the nickname "Grand Old Man of the Army."

The Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854 caused more tension. It led to violent clashes between pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups in Kansas. This divided both major parties. Pierce was not re-nominated. The Whig Party collapsed. In the 1856 election, Buchanan won. Sectional tensions grew after the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Buchanan could not heal the divisions. Some Southern leaders openly wanted to leave the Union.

In 1859, Buchanan sent Scott to settle a dispute with Britain over the San Juan Islands. Scott reached an agreement to reduce military forces on the islands. This resolved the "Pig War" peacefully.

In the 1860 election, Abraham Lincoln won. Fearing secession, Scott advised Buchanan to strengthen federal forts in the South. He was initially ignored. But Scott gained influence after the Secretary of War was replaced. Scott helped convince Buchanan to reinforce Washington, D.C., Fort Sumter, and Fort Pickens. Meanwhile, several Southern states left the Union and formed the Confederate States of America.

Scott was from Virginia. Lincoln sent an envoy to ask if Scott would remain loyal to the U.S. and keep order during Lincoln's inauguration. Scott replied, "I shall consider myself responsible for [Lincoln's] safety." He helped ensure Lincoln arrived safely and that the inauguration was secure.

Lincoln Administration and Retirement

When Lincoln took office, seven states had seceded. They had seized federal property. But the U.S. still controlled Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens. Scott advised evacuating the forts. He thought trying to resupply them would increase tensions and be impossible. Lincoln rejected this advice and chose to resupply the forts. Scott accepted the orders, but his resistance and poor health weakened his standing. Still, he remained a key military adviser.

On April 12, Confederate forces attacked Fort Sumter, forcing its surrender. On April 15, Lincoln declared a rebellion and called for militiamen. Scott advised Lincoln to offer Robert E. Lee command of the Union forces. But Lee chose to serve the Confederacy.

Scott worked to turn Union military personnel into a strong fighting force. Lincoln did not want to expand the regular army. The Union would rely on volunteers. Scott developed a strategy called the Anaconda Plan. This plan called for capturing the Mississippi River and blocking Southern ports. By cutting off the eastern Confederate states, Scott hoped to force surrender with minimal loss of life. Scott's plan was leaked and criticized by Northern newspapers. They wanted an immediate attack on the Confederacy.

Scott was too old for battlefield command. Lincoln chose General Irvin McDowell to lead the main Union army. Scott thought McDowell was uncreative and inexperienced. Scott advised that the army needed more training time. But Lincoln ordered an attack on the Confederate capital, Richmond. McDowell's force met the Confederate Army at the First Battle of Bull Run. The Union suffered a major defeat. This ended hopes for a quick end to the war.

McDowell received most of the blame for the defeat. But Scott, who helped plan the battle, also faced criticism. Lincoln replaced McDowell with McClellan. Lincoln started meeting with McClellan without Scott. Frustrated, Scott resigned in October 1861. Scott favored General Henry Halleck as his successor. But Lincoln made McClellan the army's senior officer.

Retirement and Final Years

In his last years of service, Scott became very heavy. He could not ride a horse or walk far without resting. He often had poor health, suffering from gout and other conditions. After retiring, he traveled to Europe with his daughter. In Paris, he helped calm a diplomatic incident with Britain called the Trent Affair.

When he returned from Europe in December 1861, he lived alone in New York City and at West Point, New York. He wrote his memoirs and closely followed the Civil War.

On June 23–24, 1862, President Lincoln visited West Point. He spent five hours talking with Scott about the Civil War. After McClellan's defeat, Lincoln took Scott's advice. He appointed General Halleck as the army's senior general. In 1864, Scott sent a copy of his new memoirs to Ulysses S. Grant. Grant had replaced Halleck as the lead Union general. Scott wrote on the copy, "from the oldest to the greatest general." Grant led the Union to victory using a strategy similar to Scott's Anaconda Plan. Robert E. Lee's army surrendered in April 1865.

Scott died at West Point on May 29, 1866, almost 80 years old. President Andrew Johnson ordered flags flown at half-staff to honor him. Many leading Union generals attended Scott's funeral. He is buried at the West Point Cemetery.

Legacy and Recognition

Historical Reputation

Winfield Scott holds the record for the longest active service as a general in the U.S. Army. He also served the longest as the army's chief officer. Historians say Scott was one of America’s greatest generals. However, he served in wars that were less famous than the American Revolution or the Civil War.

Historian John Eisenhower called Scott "an astonishing man." He was the country's "most prominent general" between 1821 and 1861. The Duke of Wellington called Scott "the greatest living general" after he captured Mexico City. Robert E. Lee wrote that Scott was the main reason for their success in Mexico. Historians Scott Kaufman and John A. Soares Jr. say Scott was a skilled diplomat. He helped prevent war between Britain and the United States after the War of 1812.

Scott was also known for caring about his soldiers. For example, when cholera broke out among his troops, he learned how to treat it. He risked his own health to care for the sick soldiers.

Scott received several honorary degrees. These included a Master of Arts from Princeton University in 1814. He also received a Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) from Columbia University in 1850 and from Harvard University in 1861.

Memorials and Honors

Many places and things are named after Winfield Scott. Several counties are named for him, including Scott County, Iowa, Scott County, Kansas, and Scott County, Virginia. Communities like Winfield, Illinois, Winfield, Indiana, and Fort Scott, Kansas also bear his name.

Fort Winfield Scott was part of San Francisco Bay's defenses. Lake Winfield Scott in Georgia and Mount Scott in Oklahoma are also named after him. The Scott's oriole, a type of bird, is named in his honor.

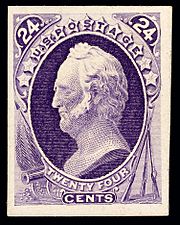

A statue of Scott stands at Scott Circle in Washington, D.C. His picture was also on a U.S. postage stamp. A paddle steamer and a US Army tugboat were named Winfield Scott. Several people, including generals and an admiral, were named after him. The US Army Civil Affairs Association sees General Scott as the 'Father of Civil Affairs'.

The General Winfield Scott House in New York City was named a National Historic Landmark in 1975. Scott's important papers are kept at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan.

Dates of Rank

Winfield Scott's military career ended when he retired on November 1, 1861. During his service, he was promoted from captain to brevet lieutenant general. Here are the dates of his promotions:

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Captain | Regular Army | May 3, 1808 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Regular Army | July 6, 1812 | |

| Colonel | Regular Army | March 12, 1813 | |

| Brigadier General | Regular Army | March 9, 1814 | |

| Brevet Major General | Regular Army | July 25, 1814 | |

| Major General | Regular Army | June 25, 1841 | |

| Brevet Lieutenant General | Regular Army | March 29, 1847 | |

| Brevet Lieutenant General | Retired | November 1, 1861 |

See also

In Spanish: Winfield Scott para niños

In Spanish: Winfield Scott para niños

- List of major generals in the United States Regular Army before 1 July 1920

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |