Valley of Mexico facts for kids

The Valley of Mexico (called Valle de México in Spanish, and Anahuac in Nahuatl, meaning "Land Between the Waters") is a high flat area in central Mexico. It's surrounded by tall mountains and volcanoes. This valley was once home to many ancient civilizations, like the Teotihuacan, the Toltec, and the Aztec Empire.

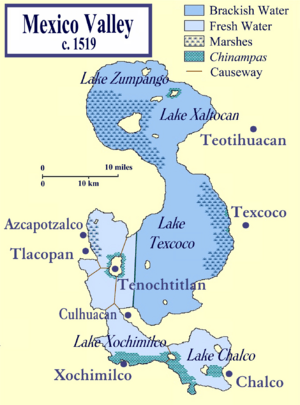

Long ago, the valley had five connected lakes: Lake Zumpango, Lake Xaltocan, Lake Xochimilco, Lake Chalco, and the biggest, Lake Texcoco. These lakes covered about 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles) of the valley floor. When the Spanish arrived in 1519, about one million people lived here, making it one of the most crowded places in the world.

After the Spanish took over the Aztec Empire, they rebuilt the main city, Tenochtitlan, and called it Mexico City. Over time, they started draining the lakes to stop floods. Today, the Valley of Mexico is mostly covered by the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. It also includes parts of the State of Mexico, Hidalgo, Tlaxcala, and Puebla.

The valley is about 2,200 meters (7,200 feet) above sea level. The mountains around it are over 5,000 meters (16,400 feet) high. It's like a big bowl with no natural way for water to flow out to the sea. All the water from rain and melting snow collects here. Sadly, all the native fish in the valley's waters died out by the end of the 1900s. Today, water from the valley flows out through man-made canals to the Tula River and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. Earthquakes happen often here, so it's an earthquake-prone area.

People have lived in this valley for at least 12,000 years. They were drawn by the mild climate (around 12 to 15 °C or 54 to 59 °F), lots of animals to hunt, and good land for farming. Important civilizations like the Teotihuacan (800 BC to 800 AD), the Toltec Empire (10th to 13th century), and the Aztec Empire (1325 to 1521) grew here.

After the Spanish arrived, the population dropped because of fighting and diseases. But by 1900, it was over one million again. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the population has grown very fast, along with many industries. Since 1900, the number of people has doubled every 15 years. Now, about 21 million people live in the Mexico City area, covering almost the entire valley.

This huge growth in a closed valley has caused big problems with air and water quality. Winds and weather patterns trap pollution in the valley. Also, too much water is pumped from underground, causing the city to sink below where the lakes used to be. This makes flooding worse and puts a lot of stress on the valley's drainage system.

History of People in the Valley

First People in the Valley

The Valley of Mexico was a great place for early humans. It had many different plants and animals, and good land for farming. People in this area started farming instead of just hunting and gathering between the end of the Ice Age and the beginning of our current time period.

The oldest known human settlement in the valley is Tlapacoya. It was on the edge of Lake Chalco. Scientists believe people lived there as far back as 12,000 BC. After 10,000 BC, more tools and signs of human life are found. Other early sites exist, but their exact dates are not yet known.

Giant Columbian mammoths used to live here. The valley has many places where mammoths were hunted. Most of these sites are near where Lake Texcoco used to be. Mammoth bones are still found by farmers today. The symbol for one of Mexico City's subway stations, Talisman, is a mammoth because many bones were found during its construction. The best place to see mammoth remains is at the Paleontological Museum in Tocuila.

Early Civilizations Before Teotihuacan

Tlatilco was an important ancient village in the Valley of Mexico. It was one of the first big settlements in the valley. It grew on the western shore of Lake Texcoco between 1200 BC and 200 BC. The people of Tlatilco were farmers, growing beans, squash, and chili peppers. They were strongest from 1000 to 700 BC.

Another old civilization was in the south of the valley, called Cuicuilco. This ancient site is now partly buried under lava from a volcano. Cuicuilco was a city by 1200 BC. It started to decline around 100 BC to 150 AD because of volcanic eruptions.

Teotihuacan and the Toltecs

About 2,000 years ago, the Valley of Mexico became one of the most crowded places in the world, and it still is. After Cuicuilco declined, people moved north to Teotihuacan and later to Tula.

Teotihuacan started as a village around 800 BC. It grew very big around 200 BC. At its peak, it had about 125,000 people and covered 20 square kilometers (7.7 square miles). It was important for trading obsidian (a type of volcanic glass) and was a major religious center. In the early 700s AD, Teotihuacan became less important as the Toltec empire grew. People then moved to Tula, north of the valley.

Aztec Empire

After the Toltec empire ended in the 1200s, people moved back to the lake areas of the valley. Many small city-states, each with its own religious center, grew up around the lakes. These cities, including the powerful Tenochtitlan, claimed to be descendants of the Toltecs.

Tenochtitlan was the biggest and most powerful city when the Spanish arrived. The Mexica people (Aztecs) founded it on a small island in Lake Texcoco in 1325. They expanded it using chinampas, which were floating gardens or artificial islands for farming. The Aztecs also built dikes, canals, and gates to control the lake's water. They brought fresh water to the city from mountain springs using aqueducts.

Even though Tenochtitlan was powerful, it needed resources from other parts of the valley. This led to the Aztec Triple Alliance with Texcoco and Tlacopan. By 1519, Tenochtitlan was the strongest, which caused problems that the Spanish used to their advantage. By 1520, over 1,000,000 people lived in the valley.

Spanish Rule and Mexico City Today

After the Spanish conquered the Aztec empire in 1521, they rebuilt Tenochtitlan and renamed it Mexico City. The city grew as the lakes shrank. After the conquest, the population dropped due to disease and violence, especially among native people. But it grew steadily through the colonial period and after Mexico became independent.

By the early 1900s, Mexico City's population was over one million. It has doubled about every 15 years since 1900. This growth is partly because the government focused on developing this area. This brought in businesses and more people. Since the 1950s, the city has spread beyond its original borders into the surrounding states, forming the huge Mexico City Metropolitan Area.

Today, this area does 45% of Mexico's industrial work and has 25% of the country's population. Much of this growth has happened on the mountainsides, with illegal settlements in important natural areas. The urban area has grown from about 90 square kilometers (35 square miles) in 1940 to 1,160 square kilometers (448 square miles) in 1990. The metropolitan area now has about 21 million people and 6 million cars.

Air Pollution Challenges

Mexico City has serious air pollution problems. This is because it's high up, surrounded by mountains, and has specific wind patterns. The high altitude means fuels don't burn completely, creating harmful gases like nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide. The mountains trap the smog, and the winds inside the valley just move the pollution around instead of pushing it away.

A major problem in winter is "thermal inversion." This is when cooler air near the ground gets trapped by warmer air above it. This keeps pollution close to the city. Also, winds from outside the valley blow pollution into the valley's main opening, where many industries are located. In summer, the situation improves with rain, but the strong sunlight still creates dangerous levels of ozone.

While still polluted, the air is better than it was decades ago. Lead pollution was controlled by using unleaded gasoline. Carbon monoxide and sulfur dioxide levels have also been reduced. The main problems now are ozone and tiny particles (soot) in the air. Mexico City often has levels of these tiny particles that are higher than what the World Health Organization recommends.

In the 1940s, before so much pollution, you could see for about 100 kilometers (60 miles) in the valley. You could see the snow-capped volcanoes like Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl every day. Now, the average visibility is only about 1.5 kilometers (1 mile). The mountain peaks are rarely visible from the city.

Dr. Mario J. Molina, a Nobel Prize winner, studied the effects of pollution here. He says tiny particle pollution is the biggest concern because it damages lungs. He estimates that people in the city lose about 2.5 million workdays each year due to health problems from these particles.

Water in the Valley

The Valley of Mexico is a closed basin, meaning water doesn't naturally flow out. It has three main water zones: the low flat area (where the lakes used to be), the foothills, and the surrounding mountains. The old lakebeds are mostly clay and are now covered by the city. Rain and melting snow from the mountains flow into the valley's water system. This underground water feeds five main sources that provide much of Mexico City's drinking water.

The Old Lake System

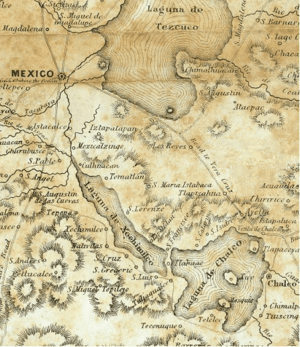

Before the 1900s, the Mexico City part of the valley had a chain of lakes. The northern lakes near Texcoco were salty, and the southern ones were fresh. The five lakes – Zumpango, Xaltocan, Xochimilco, Chalco, and the largest, Texcoco – covered about 1,500 square kilometers (580 square miles). Smaller mountains partly separated them. All the other lakes flowed into the lower Lake Texcoco, which became salty as water evaporated. Rivers from the mountains fed these lakes with runoff and melted snow.

The lake system had been shrinking for a long time due to climate change. Warmer temperatures meant more evaporation and less rain. By the time of the Aztecs, the northern lakes were too shallow for canoes during the dry season.

Controlling Water in the Valley

For 2,000 years, people have changed the water system in the valley, especially in the lake areas. The Aztecs built dikes to control floods and to keep the salty water of the northern lakes separate from the fresh water in the south. After the Spanish destroyed Tenochtitlan in 1521, they rebuilt the Aztec dikes, but they weren't enough to stop floods.

The Spanish started a huge project called the desagüe (drainage) to drain the area and control floods. This project continued throughout the entire colonial period. The idea for drainage canals came after a big flood in 1555. The first canal was started in 1605 to drain Lake Zumpango northwards. This would also send water from the Cuautitlán River away from the lakes and towards the Tula River.

This project was led by Enrico Martínez, who worked on it for 25 years. He built a canal called Nochistongo, which sent water to the Tula Valley. But it wasn't enough to prevent the Great Flood of 1629 in the city. Another canal, called the "Grand Canal," was built later. It's 6.5 meters (21 feet) wide and 50 kilometers (31 miles) long. The drainage project continued after Mexico became independent. President Porfirio Díaz officially completed it in 1894, though work still went on. Even with the Grand Canal, flooding in the city didn't stop completely.

In the 1900s, Mexico City started to sink quickly. Pumps had to be installed in the Grand Canal because it could no longer drain the valley using only gravity. The Grand Canal was also extended with a new tunnel. Even so, the city still had floods in 1950 and 1951. The Grand Canal can still move a lot of water out of the valley, but less than before. This is because the city continues to sink (as much as 7 meters or 23 feet in some areas), which weakens the water system.

Because of this, another tunnel, called the Emisor Central, was built for wastewater. This tunnel is very important, but it's been damaged by overuse and corrosion. There's worry that it might fail soon, especially during the rainy season. If it fails, it could cause huge floods in the city center, the airport, and eastern neighborhoods.

So, a new drainage project costing US$1.3 billion is planned. It will include new pumping stations, a new 30-mile (48 km) drainage tunnel, and repairs to the existing pipe system.

Pumping too much groundwater in the 1900s made the lakes disappear faster. The old lake beds are now mostly paved over. Only some canals in Xochimilco remain, mainly for tourists who ride on colorful boats called trajineras. The drying up of the lakes has had a big impact on the environment of the Valley of Mexico.

Drinking Water and Sinking Land

Historically, Mexico City got its drinking water from mountain springs through aqueducts. The Aztecs first built these, and the Spanish rebuilt them. In the mid-1800s, fresh groundwater was found under the city, leading to many wells being drilled. Today, 70% of Mexico City's water still comes from five main underground water sources in the valley. These sources are refilled by natural springs and rain.

When the population reached about six million, Mexico City started needing water from outside the valley. Today, Mexico City has a serious water shortage. Because of more people, more industries, and deforestation in the surrounding mountains, more water is leaving the system than entering it. It's estimated that the city needs 63 cubic meters (16,640 gallons) of water per second. But the main underground water source is being pumped at 55.5 cubic meters (14,660 gallons) per second, and it's only refilling at 28 cubic meters (7,400 gallons) per second. This means there's a big shortfall.

This over-pumping of groundwater from the old clay lake bed is causing the land the city is built on to sink. This problem started in the early 1900s because of the valley's drainage for flood control. Since then, some parts of Mexico City have sunk 9 meters (30 feet). For example, the El Ángel de la Independencia statue, built in 1910, was originally at street level. But because the street has sunk around it, steps have been added to reach its base.

The sinking land causes flooding problems because much of the city is now below the natural lake floor. Pumps have to work 24 hours a day to control runoff and wastewater. Despite this, flooding is still common, especially in the summer rainy season, in lower areas like Iztapalapa. Residents often build small walls in front of their homes to stop polluted rainwater from entering. The sinking also damages water and sewer pipes, which can contaminate the drinking water and pose health risks.

Other measures have been taken to control flooding. In 1950, dikes were built to hold storm runoff. Rivers that run through the city were put into concrete tunnels in 1950 and 1951. Rivers like the Consulado River and Churubusco River are now in tunnels that send their water directly to the drainage system, out of the valley. Two other rivers, the San Javier and Tlalnepantla, are diverted before they reach the city. Their water now flows directly into the Grand Canal. No water from these rivers is allowed to sink into the ground to refill the underground water sources.

While mountain streams still start naturally, as they pass through poor neighborhoods without proper sanitation, they become like open sewers. So, their final parts are often put into tunnels or added to existing major tunnels to prevent this polluted water from contaminating the underground water supply.

See also

In Spanish: Valle de México para niños

In Spanish: Valle de México para niños

- Mexican Plateau

- Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt

- Valleys of Mexico