Second Seminole War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Second Seminole War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seminole Wars and Indian removal | |||||||

Rampage during the Second Seminole War. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Seminole | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Andrew Jackson Martin Van Buren William Henry Harrison John Tyler Duncan Lamont Clinch Francis L. Dade (1835) † Winfield Scott (1836) David Moniac (1836) † Richard Keith Call (1836) Richard Gentry (1837) † Thomas S. Jesup (1836–38) Zachary Taylor (1838–40) Walker Keith Armistead (1840–41) William Jenkins Worth (1841–42) |

Osceola John Horse Holata Mico (Billy Bowlegs) Abiaca (Sam Jones) Micanopy Coacoochee (Wild Cat) Halleck Tustenuggee Halpatter Tustenuggee (Alligator) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| more than 9,000 in 1837 cumulative 10,169 regulars, 30,000 militia and volunteers | 900–1,400 warriors in 1835, fewer than 100 in 1842 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,600 military, unknown civilian | 3,000 | ||||||

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a long fight in Florida from 1835 to 1842. It was between the United States and groups called Seminoles. These groups included Native Americans and Black Seminoles. This war was part of a bigger series of conflicts known as the Seminole Wars. Many people consider the Second Seminole War to be the longest and most expensive of all the Indian conflicts in the United States.

Contents

- Why the Second Seminole War Started

- The Dade Massacre

- General Gaines's Expedition

- General Scott's Plan

- The Army Retreats, Governor Call Tries Again

- Jesup Takes Command

- Truce and Escape

- Captures and Tricky Tactics

- Zachary Taylor and the Battle of Lake Okeechobee

- The Battle of Loxahatchee

- Jesup Steps Down; Zachary Taylor Takes Command

- Macomb's Peace and the Harney Massacre

- New Tactics

- The "Mosquito Fleet"

- Indian Key Attack

- Revenge and Talks

- Colonel Worth Takes Charge

- The War Ends

- Costs of the War

- After the War

- See also

Why the Second Seminole War Started

People from different Native American tribes in the southeastern United States moved into Florida in the 1700s. These groups included the Creek people, Yamasees, and others. The Creeks were the largest group. One group of Creek speakers, the Mikasuki, settled near what is now Lake Miccosukee. Another group settled near the Alachua Prairie.

The Spanish in St. Augustine called the Alachua Creeks cimarrones. This word meant "wild ones" or "runaways." This is likely where the name "Seminole" came from. Over time, this name was used for all the different groups in Florida. But the Native Americans still saw themselves as members of different tribes.

The United States and Spain disagreed about Florida after the American Revolutionary War. The U.S. said Spain was helping runaway slaves and not stopping Native Americans from raiding U.S. lands. In 1818, Andrew Jackson led an invasion of Florida. This led to the First Seminole War.

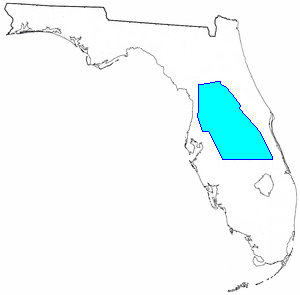

The United States bought Florida from Spain in 1819. They officially took control in 1821. Now that Florida was part of the U.S., settlers wanted the Seminoles to move away. In 1823, the government made a deal called the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminoles. This treaty set up a special area, called a reservation, for them in central Florida.

Moving to the Reservation

The Seminoles gave up their lands in northern Florida. They slowly moved to the reservation. There were some small fights with European Americans. Colonel Duncan Lamont Clinch was in charge of the Army in Florida. Fort King was built near the reservation.

By 1827, the Army said the Seminoles were on the reservation and Florida was peaceful. This peace lasted five years. During this time, many people wanted the Seminoles to be moved west of the Mississippi River. The Seminoles did not want to move. They especially did not want to be put on the Creek reservation. Most European Americans thought the Seminoles were just Creeks who had recently moved to Florida. But the Seminoles said Florida was their home. They said they were not connected to the Creeks.

Runaway slaves were a constant problem between Seminoles and European Americans. Many African Americans who escaped slavery found freedom in Florida under Spanish rule. They became known as Black Seminoles. They formed their own communities near Seminole villages. The two groups had strong friendships but kept their own cultures. People who owned slaves in nearby states worried about these free Black Seminoles. They often accused the Seminoles of stealing their slaves. But sometimes, white people raided Florida and took Black Seminoles by force.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson, a former enemy of the Seminoles, became President. In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. This law aimed to move Native Americans, including the Seminoles, west of the Mississippi River.

Treaty of Payne's Landing

In 1832, Seminole leaders met at Payne's Landing. They signed a treaty that said the Seminoles would move west if the land was good. They would live on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe. Seven chiefs went to see the new land.

When the chiefs came back to Florida, most of them said they did not sign the treaty. Or they said they were forced to sign it. They also said they could not make decisions for all the tribes. Even some U.S. Army officers said the chiefs were "tricked and pushed into signing."

The United States Senate approved the Treaty of Payne's Landing in 1834. The treaty gave the Seminoles three years to move west. The government said the three years started in 1832. So, they expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. Fort King was reopened in 1834. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, was in charge of getting the Seminoles to move.

Thompson met with the chiefs in October 1834. The Seminoles told him they would not move. They said they did not feel bound by the treaty. Thompson asked for more soldiers at Fort King and Fort Brooke. He reported that the Seminoles bought a lot of gunpowder and lead. General Clinch also warned that the Seminoles would not move without force.

In March 1835, Thompson read a letter from President Andrew Jackson to the chiefs. Jackson said, "If you... refuse to move, I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for 30 days to reply. A month later, they said they would not move. Thompson and the chiefs argued. General Clinch had to step in to stop a fight. Eight chiefs finally agreed to move but asked to wait until the end of the year. Thompson and Clinch agreed.

Five important Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy, did not agree to move. Thompson removed them from their positions. As relations got worse, Thompson stopped selling guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola, a young warrior, was very angry about this. He felt it treated Seminoles like slaves. He said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood." Thompson had Osceola locked up for a night. To get out, Osceola agreed to follow the treaty.

The situation got worse. Some European Americans attacked Native Americans. In August 1835, a soldier was killed by Seminoles while carrying mail. In November, Chief Charley Emathla wanted to avoid war. He led his people to Fort Brooke to go west. Other Seminoles saw this as a betrayal. Osceola met Charley Emathla and killed him.

The Dade Massacre

As it became clear the Seminoles would fight, Florida got ready for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked for 500 guns. Five hundred volunteers were called up. Native American war parties attacked farms and homes. Families fled to forts or left the area. A group led by Osceola attacked a supply train, killing eight guards. Sugar plantations along the coast were destroyed. Many enslaved people from these plantations joined the Seminoles.

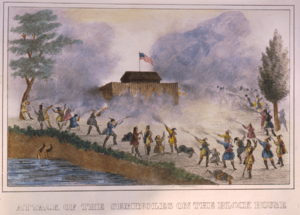

The U.S. Army had about 550 soldiers in Florida. Fort King had only one company of soldiers. It was feared they might be attacked. Two companies, 110 men, left Fort Brooke on December 23, 1835. They were led by Major Francis L. Dade. Seminoles watched the soldiers for five days. On December 28, the Seminoles attacked the soldiers. They killed all but three men. This event became known as the Dade Massacre. Only two white men survived the battle. On the same day, Osceola and his followers killed Wiley Thompson and six others outside Fort King.

In February, Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock found the remains of Dade's group. He wrote in his journal that the government was wrong. He felt the Native Americans were bravely defending their land against an unfair treaty.

On December 29, General Clinch left Fort Drane with 750 soldiers. They went to a Seminole stronghold called the Cove of the Withlacoochee. When they reached the Withlacoochee River, they could not find a place to cross. Clinch had his regular troops cross in one canoe. Once they were across, the Seminoles attacked. The troops fought back with bayonets. Four soldiers died and 59 were wounded.

On January 6, 1836, Seminoles attacked a plantation on the New River. They killed a family and their tutor. Other people in the area fled to Key West. On January 17, volunteers and Seminoles fought south of St. Augustine. The volunteers lost four men.

General Gaines's Expedition

The American army was very small then, with less than 7,500 men. It was spread out across the country. State militias and volunteers helped when more troops were needed. As news of the fighting spread, Major General Winfield Scott was put in charge of the war. Congress gave $620,000 for the war. Volunteers started forming in Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina. General Gaines gathered 1,100 soldiers and volunteers in New Orleans. He sailed with them to Fort Brooke.

Gaines found Fort Brooke low on supplies. He thought General Scott had sent supplies to Fort King. So, Gaines led his men to Fort King. Along the way, they found the Dade Massacre site. They buried the bodies in three mass graves. Gaines's group reached Fort King after nine days. It was also low on supplies. Gaines got seven days' worth of food from General Clinch. Then, Gaines headed back to Fort Brooke. He took a different route to try to find the Seminoles. He hoped to fight them in their stronghold in the Cove of the Withlacoochee River.

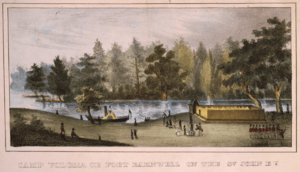

Gaines's group reached the same spot on the Withlacoochee where Clinch had fought earlier. It took another day to find a crossing point. General Gaines was stuck. He could not cross the river, and his men were running out of food. Gaines had his men build a fort called Camp Izard. He sent a message to General Clinch. Gaines hoped the Seminoles would gather around Camp Izard. Then Clinch's forces could attack them from the side. But General Scott ordered Clinch to stay at Fort Drane.

Gaines's men soon had to eat their horses and mules. A battle went on for eight days. Clinch finally decided to disobey Scott and went to help Gaines. Clinch and his men reached Camp Izard on March 6. They chased away the Seminoles.

General Scott's Plan

General Scott started gathering men and supplies for a big attack. Three groups, totaling 5,000 men, were to meet at the Cove of the Withlacoochee. The goal was to trap the Seminoles with a very large force. Scott would go with one group. Another group would come from Volusia. The third group would come from Fort Brooke. The plan was for all three groups to arrive at the same time. This would stop the Seminoles from escaping.

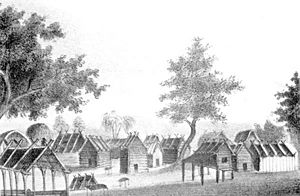

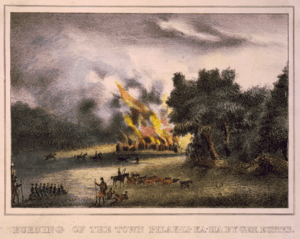

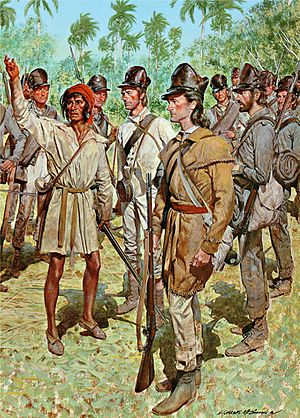

On the way to his starting point, General Eustis found Pilaklikaha, also known as Abraham's Town. Abraham was a Black Seminole leader and interpreter. He was very important during the war. Eustis burned the town before moving on.

All three groups were delayed. Eustis was two days late because of a Seminole attack. The other groups also arrived late. Clinch crossed the Withlacoochee on March 29 to attack. But he found the villages empty. Eustis's group had a small fight with some Seminoles. But overall, only a few Seminoles were killed or captured. By March 31, all three commanders were low on supplies. They headed for Fort Brooke. The mission failed to trap the Seminoles. People blamed the lack of planning time and the difficult Florida climate.

The Army Retreats, Governor Call Tries Again

April 1836 was a bad month for the Army. Seminoles attacked several forts. They also burned the sugar works on Clinch's plantation. After that, Clinch quit the Army and left Florida. Many forts were abandoned because of illness. Summer in Florida was called the "sickly season." By the end of August, another fort was abandoned. Congress gave another $1.5 million for the war. They also allowed volunteers to join for up to a year.

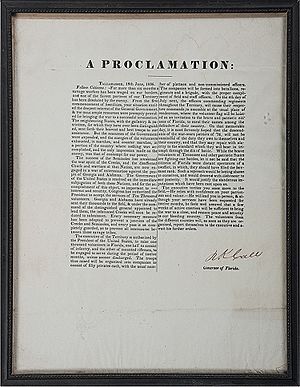

Richard Keith Call became Governor of Florida in March 1836. He suggested a summer campaign using militias and volunteers. The War Department agreed. But delays meant the campaign did not start until late September. Call also planned to attack the Cove of the Withlacoochee. He sent most of his supplies by boat. He marched his men to the Withlacoochee. They reached it on October 13. The river was flooded and could not be crossed. They had no axes to build rafts. Seminoles on the other side shot at any soldier who showed himself. Call then turned west to find the supply depot. But the supply boat had sunk. Out of food, Call led his men back to Fort Drane. This was another failed mission.

In mid-November, Call tried again. His forces crossed the Withlacoochee this time. But they found the Cove empty. Call divided his forces. On November 17, Seminoles were driven from a large camp. There was another battle the next day. The Seminoles were thought to be heading for the Wahoo Swamp. Call waited for his other group. Then he entered the Wahoo Swamp on November 21. The Seminoles fought back hard because their families were nearby. But they had to retreat across a stream. Major David Moniac, a Creek who was the first Native American to graduate from West Point, was killed trying to cross the stream.

Call faced crossing a deep stream under enemy fire. Supplies were low again. Call pulled back and led his men to Volusia. On December 9, Call was removed from command. Major General Thomas Jesup took over. He took the troops back to Fort Brooke. The volunteers' time was up, and they went home.

Jesup Takes Command

In 1836, the U.S. Army had only four Major Generals. Thomas Jesup was the last one available. Jesup had just stopped a Creek uprising. Jesup brought a new way of fighting. Instead of big attacks, he focused on wearing the Seminoles down. This needed many soldiers in Florida. Jesup eventually had over 9,000 men. About half were volunteers. He also had Marines, Navy, and Revenue Cutter Service personnel. They patrolled the coast and rivers. The Seminoles had started the war with 900 to 1,400 warriors. They had no way to replace their losses.

The Navy and Revenue Marine helped the Army from the start. Their ships carried men and supplies. They patrolled the coast to stop arms from reaching the Seminoles. Sailors and Marines helped at Army forts. They also went on expeditions into Florida.

Truce and Escape

January 1837 brought a change. Many Seminoles and Black Seminoles were captured or killed. At the Battle of Hatchee-Lustee, Marines captured horses, baggage, and 25 Native Americans and Black Seminoles, mostly women and children. In late January, some Seminole chiefs sent messages to Jesup. A truce was made. A meeting between Jesup and the chiefs happened in late February. In March, a 'Capitulation' was signed. It said Seminoles could take their allies and their "bona fide property" (meaning their Black Seminoles) with them when they moved west.

As Seminoles came to Army camps to wait for transport, slave catchers claimed many Black Seminoles. Since Seminoles had no written records, they often lost these disputes. Other white people tried to arrest Seminoles for crimes or debts. This made the Seminoles distrust Jesup's promises. By the end of May, many chiefs, including Micanopy, had surrendered. But two important leaders, Osceola and Sam Jones, had not. They strongly opposed moving. On June 2, these two leaders and about 200 followers entered a weakly guarded camp. They led away the 700 Seminoles who had surrendered.

The war did not immediately restart in a big way. Jesup thought the war was ending. Many soldiers had been sent elsewhere. It was also summer, the "sickly season." The Army did not fight much in Florida during the summer. Congress gave another $1.6 million for the war. In August, the Army stopped giving food to civilians at its forts.

Captures and Tricky Tactics

Jesup kept pressure on the Seminoles with small units. Many Black Seminoles started turning themselves in. Jesup ended up sending most of them west to join other Seminoles. On September 10, 1837, the Army captured a group of Mikasukis, including King Phillip, an important chief. The next night, they captured a group of Yuchis, including their leader, Uchee Billy.

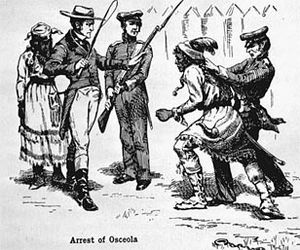

General Jesup had King Phillip send a message to his son Coacoochee (Wild Cat) to arrange a meeting. When Coacoochee arrived under a flag of truce, Jesup arrested him. In October, Osceola and Coa Hadjo, another chief, asked to meet with Jesup. A meeting was set up. When Osceola and Coa Hadjo arrived, also under a white flag, they were arrested. Osceola died in prison at Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina, within three months.

Not all captured Seminoles stayed captured. While Osceola was held at Fort Marion, 20 Seminoles escaped through a narrow window. The escapees included Coacoochee and John Horse, a Black Seminole leader. Jesup's actions were seen as unfair. He was still trying to explain them years later.

A group of Cherokees was sent to Florida to try to convince the Seminoles to move west. When Micanopy and others came to meet the Cherokees, General Jesup had the Seminoles held. John Ross, the Cherokee leader, protested. But Jesup said he had told the Cherokees that no Seminole who came in would be allowed to go home.

Zachary Taylor and the Battle of Lake Okeechobee

Jesup now had a large army. He had so many men that he had trouble feeding them all. Jesup's plan was to sweep down Florida, pushing the Seminoles further south. Colonel Zachary Taylor led a group from Fort Brooke into the middle of the state. Other groups cleared areas between rivers. A joint Army-Navy unit patrolled the lower east coast.

Colonel Taylor saw the first major fight. He left Fort Gardiner with 1,000 men on December 19. He headed towards Lake Okeechobee. On Christmas Day, 1837, Taylor's group found the main Seminole force. They were on the north shore of Lake Okeechobee.

The Seminoles, led by Alligator, Sam Jones, and Coacoochee, were hidden in a swampy area. The ground was thick mud. Taylor had about 800 men, while the Seminoles had less than 400. Taylor sent the Missouri volunteers in first. Many were killed before they pulled back. Next, 200 soldiers attacked. They lost many men before they also pulled back. Then, the 4th Infantry attacked. This time, the troops pushed the Seminoles out of the swamp towards the lake. Taylor then attacked their side. But the Seminoles escaped across the lake. Only about a dozen Seminoles were killed. Still, the Battle of Lake Okeechobee was called a big victory for Taylor and the Army.

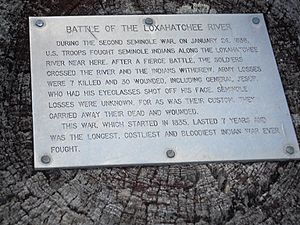

The Battle of Loxahatchee

Taylor joined other groups moving down Florida. They passed on the east side of Lake Okeechobee. On January 15, a Navy group under Lt. Levin Powell found a Seminole camp. They were outnumbered. An attack failed. The troops returned to their boats after losing four dead and 22 wounded. At the end of January, Jesup's troops found a large group of Seminoles east of Lake Okeechobee. The Seminoles were in a swamp. Cannon fire pushed them back across the Loxahatchee River. They fought again there. The Seminoles eventually disappeared. They caused more casualties than they received. This was the Battle of Loxahatchee.

The fighting slowed down. In February 1838, Seminole chiefs offered to stop fighting if they could stay south of Lake Okeechobee. Jesup liked the idea. He thought it would be easier to gather them later. But Jesup had to get approval from Washington. The chiefs and their followers camped near the Army. There was friendly interaction between them. However, the Secretary of War said no. He told Jesup to keep fighting. Jesup called the chiefs to his camp, but they refused to come. Jesup sent soldiers to capture them. The Seminoles did not fight much.

Loxahatchee River Battlefield Park protects an area where fighting happened. There are also memorials in Jonathan Dickinson State Park.

Jesup Steps Down; Zachary Taylor Takes Command

Jesup asked to be removed from his command. As summer came in 1838, the number of soldiers in Florida dropped to about 2,300. In May, Zachary Taylor, now a General, took command. With fewer soldiers, Taylor focused on keeping the Seminoles out of northern Florida. This would allow settlers to return home. But Seminoles could still reach far north. In July, they were blamed for deaths near Tallahassee and in Georgia. Fighting slowed in summer as soldiers moved to the coasts. The Seminoles focused on growing crops and gathering food.

Taylor's plan was to build small forts often across northern Florida. These forts would be connected by roads. Larger groups would search specific areas. This was expensive, but Congress kept providing money. In October 1838, Taylor moved the last Seminoles living near the Apalachicola River to Indian Territory. Killings near Tallahassee made Taylor move soldiers from southern Florida to protect the north. The winter was quiet. The Army killed few Seminoles and sent less than 200 west. Nine U.S. troops were killed. By spring 1839, Taylor reported building 53 new forts and 848 miles of roads.

Macomb's Peace and the Harney Massacre

By 1839, support for the war was decreasing. Many people thought the Seminoles deserved to stay in Florida. The cost and time to remove all Seminoles were too high. Congress gave $5,000 to make a deal with the Seminoles. President Martin Van Buren sent General Alexander Macomb to negotiate a new treaty. The Seminoles remembered broken promises. They were slow to respond. Finally, Sam Jones sent his chosen leader, Chitto Tustenuggee, to meet Macomb. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced an agreement. The Seminoles would stop fighting. In return, they would get a reservation in southern Florida.

The agreement seemed to hold through the summer. There were few killings. A trading post was set up on the Caloosahatchee River. The Seminoles who came there seemed friendly. A group of 23 soldiers was at the trading post. On July 23, 1839, about 150 Native Americans attacked the post. Some soldiers, including Colonel William S. Harney, escaped by boat. But most soldiers and civilians were killed. The war was on again.

The Americans did not know which group attacked. Many blamed the 'Spanish' Indians, led by Chakaika. Some suspected Sam Jones. Jones promised to hand over the attackers in 33 days. Meanwhile, Sam Jones's group near Fort Lauderdale stayed friendly with soldiers. On July 27, they invited officers to a dance. The officers declined but sent two soldiers and a Black Seminole interpreter with whiskey. The Mikasuki killed the soldiers. But the Black Seminole escaped. He reported that Sam Jones and Chitto Tustenuggee were involved. In August 1839, Seminole groups raided as far north as Fort White.

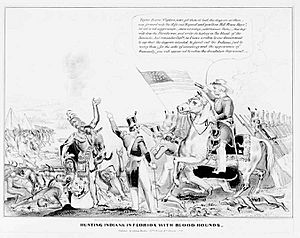

New Tactics

The Army decided to use bloodhounds to track the Seminoles. In early 1840, Florida bought bloodhounds from Cuba. They also hired Cuban handlers. The dogs had mixed results. People worried the dogs would attack women and children. The Secretary of War ordered the dogs to be muzzled and on leashes. Bloodhounds could not track through water. Also, they were trained to track African Americans. They struggled to track Native Americans.

In northern Florida, Taylor's system of forts kept the Seminoles moving. But the Army could not clear them out. Attacks on travelers were common. In February 1840, the mail stage was attacked. In May, Seminoles attacked a theater group, killing six people. In the same month, a group of soldiers was attacked. Six men pursuing the Native Americans were also killed.

In May 1840, Zachary Taylor left Florida. He was replaced by General Walker Keith Armistead. Armistead started an attack. He sent 100 soldiers at a time to search for Seminoles. For the first time, the Army fought in Florida during the summer. They captured people and destroyed crops. The Seminoles also fought back, killing 14 soldiers in July. The Army worked to find Seminole camps. They burned fields and food stores. They also drove away their animals.

Armistead planned to let the militia defend northern Florida. He wanted to use regular Army soldiers to keep the Seminoles south of Fort King. He would then chase them there. The Army destroyed camps and fields across central Florida. They destroyed 500 acres of Seminole crops by mid-summer. The Army in Florida now had many regiments.

Changes were also made in southern Florida. At Fort Bankhead, Colonel Harney trained his men in swamp and jungle fighting. The Navy took a bigger role. They sent boats with sailors and Marines up rivers and into the Everglades.

The "Mosquito Fleet"

In late 1839, Navy Lt. John T. McLaughlin led a joint Army-Navy force. This force would operate in Florida. It included schooners and cutters off the shores. Barges near the mainland would stop Cuban and Bahamian traders bringing arms to the Seminoles. Smaller boats, even canoes, patrolled rivers and the Everglades. McLaughlin set up his base at Tea Table Key.

An attempt to cross the Everglades from west to east started in April 1840. But sailors and Marines were attacked by Seminoles. Many naval personnel got sick. The expedition was called off. For the next few months, McLaughlin's force explored southern Florida's inlets and rivers. McLaughlin later led a force across the Everglades. From December 1840 to January 1841, his group crossed the Everglades from east to west in dugout canoes. They were the first white groups to do so.

Indian Key Attack

Indian Key is a small island in the upper Florida Keys. It had become a base for people who salvaged shipwrecks. In 1836, it became the main town for Dade County. Despite fears of attack, people stayed to protect their property. The islanders had six cannons and their own small militia. The Navy had a base on nearby Tea Table Key.

Early on August 7, 1840, a large group of 'Spanish' Native Americans secretly came onto Indian Key. One man saw them and raised the alarm. Of about 50 people on the island, 40 escaped. Dr. Henry Perrine, a former U.S. Consul, was among the dead. He was waiting on Indian Key until it was safe to move to land he had been given on the mainland.

The naval base on Tea Table Key had few people. Only a doctor, his patients, and five sailors were there. This small group put cannons on barges. They tried to attack the Native Americans on Indian Key. The Native Americans fired back. The cannons on the barges broke loose. The sailors had to retreat. The Native Americans burned the buildings on Indian Key after taking everything valuable.

Revenge and Talks

In December 1840, Colonel Harney got revenge for the attack on the Caloosahatchee River. He led 90 men into the Everglades. They used canoes borrowed from the Marines. A Black man named John, who had been held by Seminoles, guided them. They found some Native Americans in canoes. Harney's men chased them. They caught some and hanged the men. Harney's group found the camp of Chakaika and the 'Spanish Indians'. The soldiers dressed as Native Americans. They attacked the camp early in the morning. Chakaika was outside the camp. He tried to run, then turned to face the soldiers. He offered his hand, but a soldier shot and killed him. There was a short fight. Some Native Americans escaped. Harney hanged two captured warriors. He also had Chakaika's body hung. Harney and his men returned after 12 days. Harney lost one soldier. He had killed four Native Americans and hanged five.

Armistead had $55,000 to bribe chiefs to surrender. In November 1840, General Armistead met with chiefs. He was allowed to offer each leader $5,000 to bring their followers to move west. He could also offer land in southern Florida to those who stayed. But Armistead did not offer these terms. He insisted they agree to the old treaty. He also secretly sent soldiers to threaten one chief's people. After several days, both chiefs fled in the middle of the night.

Echo Emathla, a chief, surrendered. But most of his people did not. Other groups continued to fight. Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted $5,000 to bring in his 60 people. Smaller chiefs got $200. Every warrior got $30 and a rifle. Coacoochee used Armistead's willingness to talk. In March 1841, he agreed to bring in his followers in a few months. During that time, he visited several forts. He used a pass from Armistead. He demanded food and liquor. At one fort, Coacoochee demanded a horse and whiskey.

By spring 1841, Armistead had sent 450 Seminoles west. Another 236 were waiting to go. Armistead thought only about 300 warriors were left in Florida. In May 1841, Halleck Tustenuggee said he would surrender.

Colonel Worth Takes Charge

In May 1841, Colonel William Jenkins Worth became the new commander. The war was unpopular and expensive. Worth had to cut costs. He released nearly 1,000 civilian employees. He combined smaller commands. Worth then ordered his men on "search and destroy" missions during the summer. These efforts drove the Seminoles out of their old stronghold. Much of northern Florida was also cleared.

On May 1, 1841, Lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman escorted Coacoochee to a meeting. Coacoochee agreed to bring his people to move west in 30 days. Coacoochee's people came and went freely at the fort. But the commander thought Coacoochee would break his promise. On June 4, he arrested Coacoochee and 15 followers. Worth ordered the ship carrying them to return. He wanted to use Coacoochee to convince other Seminoles to surrender.

Worth offered Coacoochee bribes worth about $8,000. Coacoochee agreed to send messages urging Seminoles to move west. Chiefs still fighting met and agreed to kill any messengers from the whites. But when one messenger appeared at a council of southern chiefs, he was captured but not killed.

A total of 211 Seminoles surrendered because of Coacoochee's messages. This included most of his own group. Hospetarke and 127 of his group were captured in August. As fewer Seminoles remained, it was easier for them to hide. In November, the Army burned some villages in the Big Cypress Swamp. Some Seminoles in southern Florida gave up after that.

Seminoles were still spread across Florida. One starving group surrendered in northern Florida in 1842. Further east, groups led by Halpatter Tustenuggee and Halleck Tustenuggee raided settlements. On April 19, 1842, soldiers found a group of Seminole warriors. There was a brief fight. The Seminoles disappeared into a swamp. Halleck Tustenuggee was captured when he came to Fort King for talks. The rest of his group was also caught.

The War Ends

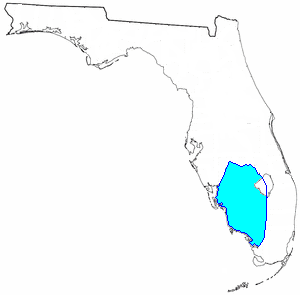

Colonel Worth suggested in early 1842 that the remaining Seminoles be left alone if they stayed in southern Florida. Worth eventually got permission to leave the remaining Seminoles on an informal reservation in southwest Florida. He could declare the war over whenever he chose. At this time, several different groups of Native Americans were still in Florida. Billy Bowlegs led a large group of Seminoles. Sam Jones led a group of Mikasukis in the Everglades. North of Lake Okeechobee was a group of Muskogees led by Chipco. Another Muskogee group, led by Tiger Tail, lived near Tallahassee.

In August 1842, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act. This law gave free land to settlers who improved the land and were ready to defend themselves. People could claim 160 acres of land in southern Florida. They had to live on the land for five years and clear five acres. But they could not claim land within two miles of a military post.

In the last action of the war, General William Bailey led 52 men. They chased a small group of Tiger Tail's warriors who had been attacking settlers. They surprised the group and killed all 24. William Wesley Hankins, at 16, was said to have fired the last shot of the war.

Also in August 1842, Worth met with the chiefs still in Florida. Each warrior was offered a rifle, money, and one year's worth of food if they moved west. Some accepted. But most hoped to move to the reservation in southwest Florida. Worth believed the remaining Native Americans would either go west or move to the reservation. He declared the war over on August 14, 1842. Worth then took a break. The Army in Florida had 1,890 men. Attacks on white settlers continued.

Worth returned to Florida in November 1842. He decided that Tiger Tail and Otiarche had taken too long to decide. He ordered them to be brought in. Tiger Tail was very sick and died waiting to be moved. Other Native Americans in northern Florida were also captured and sent west. By April 1843, only one regiment was left in Florida. In November 1843, Worth reported that only about 300 Native Americans were left in Florida. They were all living on the reservation and were no longer a threat.

Costs of the War

The Second Seminole War cost a lot of money, estimated between $30 million and $40 million. The Navy spent about $511,000. Over 10,000 Army, Navy, and Marine soldiers served in Florida. About 30,000 militiamen and volunteers also served.

The U.S. Army officially recorded 1,466 deaths, mostly from disease. About 269 officers and men were killed in action. Almost half of these deaths happened in the Dade Massacre, Battle of Lake Okeechobee, and Harney Massacre. The Navy and Marine Corps lost 41 men. About 55 volunteer officers and men were killed by the Seminoles. The number of white civilians, Seminoles, and Black Seminoles killed is not known.

By the end of 1843, 3,824 Native Americans (including 800 Black Seminoles) had been sent from Florida to what became the Indian Territory. They were first settled on the Creek Reservation, which caused problems. By 1962, their numbers had dropped to 2,343 Seminoles in the Indian Territory. About 1,500 remained in Florida.

After the War

Peace came to Florida for a while. The Native Americans mostly stayed on the reservation. But there were small fights. Florida authorities kept pushing for all Native Americans to be removed. The Native Americans tried to avoid white people as much as possible. As time passed, more serious problems happened. The government decided again to remove all Native Americans from Florida. They put more pressure on the Seminoles. This led to the Third Seminole War in 1855.

See also

In Spanish: Segunda guerra semínola para niños

In Spanish: Segunda guerra semínola para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |