Black Seminoles facts for kids

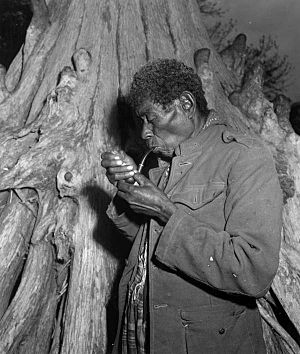

An Afro-Seminole elder smoking from a pipe (1952)

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~2,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States: Oklahoma, Florida, Texas The Bahamas: Andros Island Mexico: Coahuila |

|

| Languages | |

| English, Afro-Seminole Creole, Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Protestantism, Roman Catholicism and syncretic Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gullah, Mascogos, Seminoles |

The Black Seminoles, also known as Afro-Seminoles, are a group of people connected to the Seminole tribe in Florida and Oklahoma. Most of them are descendants of Seminole people, free Africans, and people who escaped slavery. They formed alliances with Seminole groups in Spanish Florida. Many Black Seminoles have Seminole family roots. However, because of their dark skin and curly hair, they were often seen as slaves or freed people.

Historically, Black Seminoles lived in their own groups close to Native American Seminoles. Some were held as slaves, especially by Seminole leaders. But Black Seminoles had more freedom than slaves owned by white people or other Native American tribes. They even had the right to carry weapons.

Today, many Black Seminole descendants live in communities around the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. Two of their groups, the Caesar Bruner Band and the Dosar Barkus Band, are part of the Nation's main council. Other Black Seminole communities are found in Florida, Texas, the Bahamas, and northern Mexico.

Since the 1930s, the Seminole Freedmen have faced challenges with being included in the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma. In 1990, the tribe received a large payment from the United States for land taken in Florida in 1823. The Freedmen have been trying to get a share of this money. In 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the Seminole Freedmen could not sue without the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma joining them. The Nation refused to join the lawsuit. In 2000, the Seminole Nation voted to only allow people who could prove they were descendants of a Seminole listed on the Dawes Rolls (records from the early 1900s) to be members. This rule excluded about 1,200 Freedmen who were members before. They argue that the Dawes Rolls were not always correct and often listed people with both Seminole and African ancestors only as Freedmen.

Contents

How the Black Seminoles Began

The Spanish government first tried to protect their claim to Florida by using local Indian tribes in a mission system. These Native Americans were meant to act as a local army to defend the colony from attacks by the nearby colony of South Carolina. However, attacks from South Carolina colonists and new European diseases, which the Native Americans had no protection against, quickly wiped out Florida's native population.

After most local Native Americans died out, Spanish leaders encouraged Native Americans and runaway slaves from the Southern colonies to move to Florida. The Spanish hoped that more people living in Spanish Florida would help protect against possible attacks from American colonists.

As early as 1689, black people escaped from the South Carolina Lowcountry to Spanish Florida looking for freedom. These people slowly formed what is now known as the Gullah culture. In 1693, King Charles II of Spain made a rule that black runaways would be free if they helped defend the Spanish settlers at St. Augustine. The Spanish created a black army. Their settlement at Fort Mosé, started in 1738, was the first legally recognized free black town in North America.

Not all escaped slaves wanted to serve in the military in St. Augustine. Many sought safety in the wild areas of northern Florida. Their knowledge of farming in warm climates and their resistance to tropical diseases helped them a lot. Most of the black people who first settled in Florida were Gullah people. They had escaped from the rice plantations of South Carolina and later Georgia. As Gullah people, they had developed a special language based on English and African words, along with their own culture and leadership. These Gullah pioneers built their own farming villages, growing rice and corn. They became allies with Creek and other Native Americans who were also escaping into Florida at the same time. In Florida, they developed the Afro-Seminole Creole language, which they spoke with the growing Seminole tribe.

After the Treaty of Paris (1763) in 1763, which ended the Seven Years' War, Spanish Florida was given to the Kingdom of Great Britain. The area continued to be a safe place for runaway slaves from the Southern colonies because it was not heavily settled. Many escaped black people found safety near growing Native American settlements.

In 1773, when the American naturalist William Bartram visited the area, he called the Seminole a distinct people. Their name likely came from the word "simanó-li," which means "people who move from crowded towns and live by themselves." The word "Seminole" might also come from the Spanish word cimarrón, which is also the source of the English word maroon. This word describes communities of runaway slaves in Florida, the Caribbean, and other parts of the New World.

Florida had been a safe place for runaway slaves for at least 70 years by the time of the American Revolution. Black Seminole communities were set up near the main Seminole towns. More freedom-seeking black people came to Florida during the American Revolution (1775–83), escaping during the war. During the Revolution, the Seminole sided with the British. This led to more contact between African Americans and Seminole. The Seminole, like the Creek and other Southeast Native American tribes, did own some slaves. During the War of 1812, both communities joined the British against the US. They hoped to stop American settlers. This strengthened their bond but made American general Andrew Jackson dislike them.

Spain had given land to some Muscogee (Creek) Native Americans. Over time, other small groups of Southeast American Native Americans, like the Miccosukee, Choctaw, and the Apalachicola, joined the Creek. They formed communities. Their community grew in the late 1700s and early 1800s as many Creek left present-day Georgia and Alabama. This was due to pressure from white settlers and the Creek Wars. Through this process, these Native Americans formed the Seminole tribe.

Black Seminole Culture

The Black Seminole culture that developed after 1800 was a lively mix of African, Native American, Spanish, and slave traditions. They adopted some Native American ways. For example, maroons wore Seminole clothes and ate the same foods prepared in the same ways. They gathered the roots of a plant called coontie. They ground, soaked, and strained these roots to make a starchy flour similar to arrowroot. They also mashed corn to make sofkee, a kind of porridge often used as a drink. They also brought their Gullah staple food, rice, to the Seminole. Rice remained a basic part of the diet for Black Seminoles who moved to Oklahoma.

The language of the Black Seminoles is a mix of African, Seminole, and Spanish words. Experts say the African roots of the Black Seminoles come from the Kongo, Yoruba, and other African groups. Linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner found about fifteen words spoken by Black Seminoles that came from the Kikongo language. Other African words spoken by Black Seminoles come from the Twi, Wolof, and other West African languages.

At first, living separately from the Native Americans, the maroons created their own unique African-American culture. This culture was based on the Gullah culture from the Lowcountry. Black Seminoles leaned towards a mixed form of Christianity that developed during the plantation years. Some cultural practices, like "jumping the broom" for marriage, came from the plantations. Other customs, like some names used for black towns, showed their African heritage.

Over time, the Seminole and black people had some marriages between them. However, historians and experts now believe that Black Seminoles generally had their own independent communities. They allied with the Seminole during times of war.

Seminole society was based on a matrilineal family system. This means that inheritance and family lines went through the mother. Children were considered to belong to their mother's family group. So, those born to African mothers would have been seen as black by the Seminole. While the children might learn customs from both parents' cultures, the Seminole believed they belonged more to the mother's group. African Americans adopted some parts of the European-American father-led system. But, in the Southern slave states, a law from the 1600s called partus sequitur ventrem said that children of slave mothers were legally slaves. Under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, even if a mother escaped to a free state, she and her children were legally considered slaves and runaways. Because of this, Black Seminoles born to slave mothers were always at risk of being captured and re-enslaved.

Relations Between Africans and Seminoles

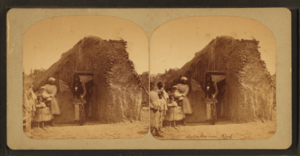

By the early 1800s, maroons (free black people and runaway slaves) and the Seminole were often in contact in Florida. They developed a unique system of relations, different from other North American Native Americans and black people. Seminole practice in Florida did allow for a type of slavery. However, it was not like the harsh chattel slavery common in the American South. It was more like a feudal system, where African Americans among the Seminole generally lived in their own communities.

In exchange for giving a yearly payment of animals, crops, or help with hunting and war parties, black prisoners or runaways found safety among the Seminole. In return, the Seminoles gained an important ally in a region with few people. The Black Seminoles elected their own leaders and could gather wealth in cattle and crops. Most importantly, they carried weapons for self-defense. Records show that Seminole and Black Seminole people owned large amounts of land in Florida. Some of this land is still owned by their descendants today. In the 1800s, white Americans called the Black Seminoles "Seminole Negroes." Their Native American allies called them Estelusti ("black People").

Under these relatively free conditions, the Black Seminoles thrived. U.S. Army Lieutenant George McCall wrote about a Black Seminole community in 1826:

We found these negroes in possession of large fields of the finest land, producing large crops of corn, beans, melons, pumpkins, and other esculent vegetables.... I saw, while riding along the borders of the ponds, fine rice growing; and in the village large corn-cribs were filled, while the houses were larger and more comfortable than those of the Native Americans themselves.

Historians believe that in the 1820s, about 800 black people lived with the Seminoles. The Black Seminole settlements were well-defended, unlike most slave communities in the Deep South. The strong military bond between Africans and Seminoles led General Edmund P. Gaines, who visited several thriving Black Seminole settlements in the 1800s, to call the African Americans "vassals and allies" of the Seminole.

The usual relationship between Black Seminoles and Native Americans changed during the Second Seminole War. The old tribal system broke down. The Seminole became loose war groups living off the land, with no difference between tribe members and black runaways. This changed again in the new territory. The Seminole had to settle on specific plots of land and start farming. Conflict arose because the Seminole were placed on land given to the Creek, who practiced chattel slavery. There was growing pressure from both Creek and pro-Creek Seminole to adopt the Creek style of slavery for the Black Seminoles. Creek slave traders and others, including white people, began raiding Black Seminole settlements to kidnap and enslave people. The Seminole leadership became led by a pro-Creek group that supported chattel slavery. These threats caused many Black Seminoles to escape to Mexico.

When it came to religion, the groups remained separate. The Seminole followed the spiritual beliefs of their Great Spirit. Black former-slaves had a mixed form of Christianity they brought from the plantations. In general, the black former-slaves never fully adopted Seminole culture and beliefs. However, they were accepted into Seminole society. They were not considered Native American by the mid-1900s.

Most black former-slaves spoke Gullah, a language based on African and English words. This allowed them to communicate better with Anglo-Americans than the Creek or Mikasuki-speaking Seminole. The Native Americans used them as translators to help with trading with the British and other tribes. Together, in Florida, they developed Afro-Seminole Creole. In 1978, linguist Ian Hancock identified it as a distinct language. Black Seminoles and Freedmen continued to speak Afro-Seminole Creole through the 1800s in Oklahoma. Hancock found that in 1978, some Black Seminole and Seminole elders still spoke it in Oklahoma and Florida.

The Seminole Wars

After winning independence in the American Revolution, American slaveholders became very worried about the armed black communities in Florida. Spain ruled the territory again, as Britain had given both East and West Florida back to Spain. US slaveholders wanted to capture and return Florida's black runaways under the Treaty of New York (1790).

General Andrew Jackson wanted to break up Florida's maroon communities after the War of 1812. He attacked the Negro Fort, which had become a Black Seminole stronghold after the British left it. Breaking up these communities was one of Jackson's main goals in the First Seminole War (1817–18).

Under pressure, the Native American and black communities moved into south and central Florida. Slaves and Black Seminoles often traveled down the peninsula to escape from Cape Florida to the Bahamas. Hundreds left in the early 1820s after the United States bought the territory from Spain in 1821. Reports from that time mention a group of 120 escaping in 1821. A much larger group of 300 African-American slaves escaped in 1823, picked up by Bahamians in 27 small boats and canoes. Their worry about living under American rule was justified. In 1821, Andrew Jackson became the governor of Florida. He ordered an attack on Angola, a village built by Black Seminoles and other free black people south of Tampa Bay. Raiders captured over 250 people, most of whom were sold into slavery. Some survivors fled deeper into Florida, and others went to Florida's east coast and escaped to the Bahamas. In the Bahamas, the Black Seminoles created a village called Red Bays on Andros. Basket making and certain grave rituals linked to Seminole traditions are still practiced there. The building of the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1825 reduced the number of slave escapes from this spot.

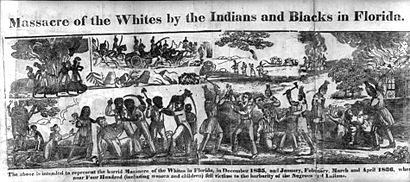

The Second Seminole War (1835–42) was the peak of conflict between the U.S. and the Seminoles. It was also the strongest point of the African-Seminole alliance. The U.S. wanted to move Florida's 4,000 Seminole people and most of their 800 Black Seminole allies to the western Indian Territory. In the year before the war, important white citizens captured and claimed at least 100 Black Seminoles as runaway slaves.

Black Seminoles did not want to be moved to the West. They feared attempts to re-enslave more of their community. In meetings before the war, they supported the most aggressive Seminole group, led by Osceola. After the war started, individual black leaders like John Caesar, Abraham, and John Horse played key roles. Besides helping the Native Americans fight, Black Seminoles encouraged plantation slaves to rebel at the start of the war. These slaves joined Native Americans and maroons in destroying 21 sugar plantations from Christmas Day 1835 through the summer of 1836. Historians debate if these events should be seen as a separate slave rebellion. Generally, they view the attacks on the sugar plantations as part of the Seminole War.

By 1838, U.S. General Thomas Sydney Jesup tried to separate the black and Seminole warriors. He offered freedom to the black people if they surrendered and agreed to move to Indian Territory. John Horse was among the black warriors who surrendered under this offer. However, because of Seminole opposition, the Army did not fully keep its promise. After 1838, more than 500 Black Seminoles traveled with the Seminoles thousands of miles to the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Some traveled by ship across the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River. Many people died along this journey, also known as The Trail of Tears, because of the harsh conditions.

The status of Black Seminoles and runaway slaves was largely unclear after they reached Indian Territory. The problem was made worse because the government first put the Seminole and black people under the control of the Creek Nation. Many Creek people owned slaves. The Creek tried to re-enslave some of the runaway black slaves. John Horse and others set up towns, usually near Seminole settlements, just as they had done in Florida.

In the West and Mexico

In the west, Black Seminoles were still threatened by slave raiders. These included pro-slavery members of the Creek tribe and some Seminole. Their loyalty to the black people lessened after their defeat by the US in the war. Officers of the federal army may have tried to protect the Black Seminoles. But in 1848, the U.S. Attorney General gave in to pro-slavery groups. He ordered the army to take away the community's weapons. This left hundreds of Seminoles and Black Seminoles unable to leave their settlement or defend themselves against slave traders.

Moving to Mexico

Facing the threat of enslavement, the Black Seminole leader John Horse and about 180 Black Seminoles made a large escape in 1849 to northern Mexico. Slavery had been ended in Mexico twenty years earlier. The black runaways crossed to freedom in July 1850. They rode with a group of traditional Seminole led by Chief Coacochee. The Mexican government welcomed the Seminole allies as border guards. They settled at Nacimiento, Coahuila.

After 1861, the Black Seminoles in Mexico and Texas had little contact with those in Oklahoma. For the next 20 years, Black Seminoles served as soldiers and Native American fighters in Mexico. There, they became known as mascogos, a name from the Creek tribe – Muskogee. Slave raiders from Texas continued to threaten the community. But weapons and help from the Mexican Army allowed the black warriors to defend their community. By the 1940s, 400–500 descendants of the Mascogos lived in Nacimiento de los Negros, Coahuila. They lived on lands next to the Kickapoo tribe. They had a successful farming community. By the 1990s, most of the descendants had moved into Texas.

Indian Territory (Oklahoma)

During this time, several hundred Black Seminoles remained in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Most of the Seminole and the other Five Civilized Tribes supported the Confederacy during the American Civil War. Because of this, in 1866, the US required new peace treaties with them. The US demanded that the tribes free any slaves and give the freedmen full citizenship rights in the tribes if they chose to stay in Indian Territory. In the late 1800s, Seminole Freedmen thrived in towns near the Seminole communities on the reservation. Most had not been living as slaves to the Native Americans before the war. They lived—as their descendants still do—in and around Wewoka, Oklahoma. This community was founded in 1849 by John Horse as a black settlement. Today, it is the capital of the federally recognized Seminole Nation of Oklahoma.

After the Civil War, some Freedmen leaders in Indian Territory practiced having more than one wife, like African leaders in other communities. In 1900, there were 1,000 Freedmen listed in the Seminole Nation's population in Indian Territory, about one-third of the total. By the time of the Dawes Rolls, many households were headed by women. The Freedmen's towns were made up of large, closely connected families.

After land was divided, "freedmen, unlike their Native American peers on the blood roll, were allowed to sell their land without getting approval from the Indian Bureau. This made the poorly educated Freedmen easy targets for white settlers moving from the Deep South." Many Seminole Freedmen lost their land in the early decades after it was divided. Some moved to cities. Others left the state because of its strict racial segregation laws. As US citizens, they faced Oklahoma's harsher racial laws.

Since 1954, the Freedmen have been included in the constitution of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. They have two groups, each representing more than one town. They are named after 19th-century leaders: the Cesar Bruner band covers towns south of Little River; the Dosar Barkus band covers several towns north of the river. Each of these groups elects two representatives to the General Council of the Seminole Nation.

Texas Community

In 1870, the U.S. Army asked Black Seminoles to return from Mexico to serve as army scouts for the United States. The black Seminole Scouts (originally an African American unit despite the name) played a main role in the Texas-Indian Wars of the 1870s. They were based at Fort Clark, Texas, where the Buffalo Soldiers were also stationed. The scouts became famous for their tracking skills and amazing endurance. Four men received the Medal of Honor, three for an action in 1875 against the Comanche.

After the Texas Indian Wars ended, the scouts remained at Fort Clark in Brackettville, Texas. The Army ended the unit in 1914. The veterans and their families settled in and around Brackettville. Scouts and family members were buried in its cemetery. The town remains an important place for the Texas-based Black Seminoles. In 1981, descendants in Brackettville and the Little River community of Oklahoma met for the first time in over a century. They gathered in Texas for a Juneteenth reunion and celebration.

Florida and Bahamas

Black Seminole descendants still live in Florida today. They can join the Seminole Tribe of Florida if they meet its rules for blood quantum: having at least one-quarter Seminole ancestry. About 50 Black Seminoles, all of whom have at least one-quarter Seminole ancestry, live on the Fort Pierce Reservation. This is a 50-acre piece of land taken into trust in 1995 by the Department of Interior for the Tribe as its sixth reservation.

Descendants of Black Seminoles, who identify as Bahamian, live on Andros Island in the Bahamas. A few hundred refugees had left in the early 1800s from Cape Florida to go to the British colony for safety from American enslavement. After banning its part in the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, Britain declared in 1818 that slaves who arrived in the Bahamas from outside the British West Indies would be set free. In 1833, Britain ended slavery throughout its Empire. These descendants are sometimes called "black Indians," recognizing their history.

Legacy and Honors

- Fort Mose Historic State Park in Florida is a National Historic Landmark. It marks the site of the first free black community in the United States.

- A large sign at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park remembers the place where hundreds of African Americans escaped to freedom in the Bahamas in the early 1820s. This is part of the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Trail.

- A sign at the Manatee Mineral Spring marks where traces of the village of Angola were found.

- Red Bays, Andros, the historic settlement of Black Seminoles in the Bahamas, and Nacimiento, Mexico, are recognized as related international sites on the Network to Freedom Trail.

Notable Black Seminoles

- Dosar Barkus, a band leader from 1892 through the time land was divided. A current band is named after him.

- Cesar Bruner, a band leader from the Reconstruction era through when Oklahoma became a state. A current band is named after him.

- Eugene Bullard

- John Horse, a leader at the time of removal, founder of Wewoka, and co-leader of the 1849 escape to northern Mexico.

- Sergeant John Ward

- Pompey Factor and Isaac Payne - Medal of Honor recipients for their service in the 24th Infantry.

See also

In Spanish: Semínolas negros para niños

In Spanish: Semínolas negros para niños