Texas–Indian wars facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Texas Indian wars |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars and the Mexican Indian Wars | |||||||

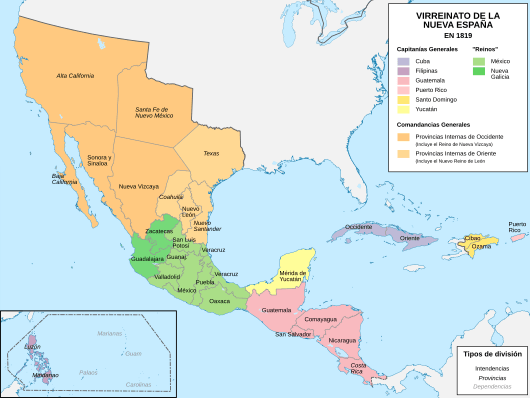

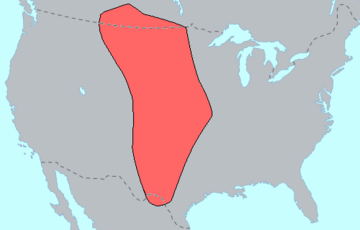

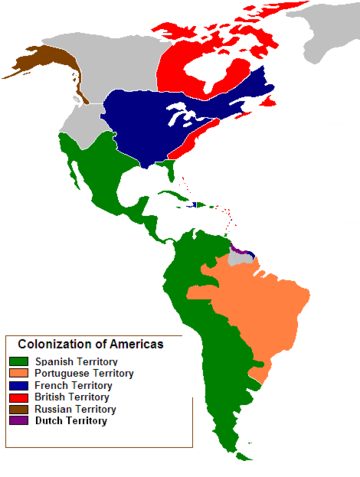

A map showing the Comanche lands (Comancheria) during the 1800s. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Other Indigenous nations |

|||||||

Texas Comanche wars 1820–1875 |

|||||||

The Texas–Indian wars were a series of fights between settlers in Texas and the Southern Plains Indians during the 1800s. These conflicts started even before many European and American settlers arrived. Spain and later Mexico wanted people to move to Texas. They hoped these new settlements would protect them from the Plains Indians.

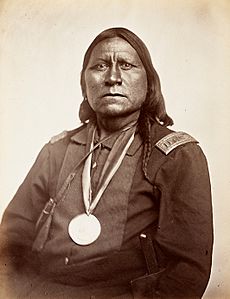

So, fights between American settlers and Plains Indians happened while Texas was still part of Mexico. The conflicts kept going after Texas became independent in 1836. They finally ended in 1875, about 30 years after Texas joined the United States. The last free group of Plains Indians, the Comanches led by Quanah Parker, gave up and moved to a reservation in Oklahoma.

This struggle between the Plains tribes and Texans became very intense. The Republic of Texas, mostly settled by Americans, was seen as a threat by the native people. These wars involved strong feelings on both sides. They led to many deaths and, in the end, the near-total takeover of the Indian lands.

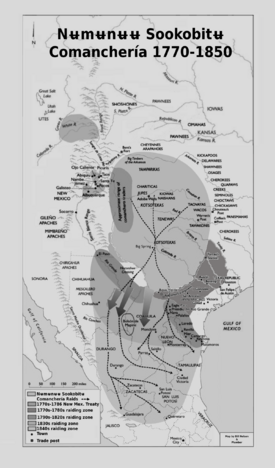

Many native tribes lived in the area. But the most powerful was the Comanche, known as the "Lords of the Plains." Their land, called Comancheria, was very strong. They often fought against the Spanish, Mexicans, Texans, and Americans. The Comanche were known as fierce fighters. They were famous for raiding, burning, and taking captives as far south as Mexico City.

Contents

Understanding the Background of the Wars

Early Native American Groups in Texas

Texas was a meeting point for two major native cultures. The Pueblo people lived to the west. The Plains tribes lived to the east. Archaeologists have found that three main native cultures lived here before Europeans arrived.

New groups of people moved into Texas over time. They competed for land and resources. Europeans began settling permanently in Texas in the late 1600s. They settled near the Rio Grande and moved north to places like San Antonio and El Paso.

The Comanche arrived in northern Texas around the early 1700s. They became the most powerful group in the late 1700s. This happened after they learned to use horses very well. Most other Plains Indians had arrived by the mid-1700s.

Native groups in northern Texas included the Southern Plains villagers. The Tonkawa were a group of tribes in central Texas. Tribes in east Texas included the Caddo. Along the Gulf coast lived the Akokisa, Atakapa, and Karankawa. The Plains Apache and Kiowa moved into Texas before Europeans came.

Spanish settlers sometimes captured Native American children. They would often baptize these children and raise them as servants. This practice first involved Apaches, and later Comanche children.

The Rise of the Comanche People

Before the mid-1600s, the Comanche were part of the Shoshone people. They lived near the Platte River in Wyoming. When they got horses, they could travel and hunt much better. This led the Comanche to become a separate tribe from the Shoshone.

They moved to the southern Great Plains, from the Arkansas River to Central Texas. Their population grew quickly. This was because of many buffalo, their use of horses for hunting and fighting, and by taking in other Shoshone and captives.

The Comanche fought with speed and skill. They became excellent horse riders and warriors. They were the most powerful Native American group on the plains. Tribes that accepted Comanche power had to provide food, lodging, and women as tribute.

When the Comanche met Spanish colonists, they stopped Spain from expanding east from New Mexico. They also prevented direct contact with new Spanish settlements. The Comanche, and later their Apache allies, launched deep raids into Mexico. They captured and enslaved thousands of Mexicans.

Eventually, Mexicans made up almost 30% of the Comanche nation. The Comanche were not a single, unified tribe. They were divided into many independent groups. These groups shared the same language and culture. Sometimes they fought each other, but at other times they worked together.

Comanche Wars with the Apaches

Before 1750, the Apaches were very strong in west Texas. But this changed when the Comanche arrived. In the 1740s, the Comanche began moving south of the Arkansas River. They settled in the Llano Estacado area, which goes from Oklahoma through the Texas Panhandle into New Mexico.

The Apaches were forced out after a series of wars. The Comanche then controlled this large area. It stretched from the Arkansas River through central Texas to San Antonio. It also included the Edwards Plateau west to the Pecos River.

Comanche Alliances with Other Tribes

After pushing out the Apaches, the Comanche suffered from a smallpox epidemic from 1780–1781. This disease was very severe. The Comanche stopped their raids for a while, and some groups broke apart. Another smallpox epidemic hit in 1816–1817. It is believed that more than half of the Comanche population died from these diseases.

Because of this huge loss, the Comanche formed an alliance with the Kiowa and Kiowa Apache. This happened after a Kiowa warrior spent time with the Comanche in 1790. They needed to protect their hunting grounds from settlers. The Kiowa and Comanche agreed to share hunting grounds and fight together. The Kiowa Apache, as allies of the Kiowa, joined this alliance too.

Europeans Arrive in Texas

European and Mexican colonists came to Texas before Spanish rule ended. Spanish leaders did not encourage many people to settle here. The area was far from their main bases. The number of colonists was very small, and they were always at risk from Comanche raids.

By the early 1800s, Mexican resistance to Comanche attacks had almost collapsed. This was due to the Comanche wars and the Mexican wars for independence.

In contrast, American settlers were seen as very good fighters. So, they were encouraged to build settlements in Texas. These settlements were meant to be a defense against Comanche raids further south. Many of these early Americans were killed or driven out by Spanish authorities. But the Comanche's deep raids into Mexico showed that Americans could hold the frontier.

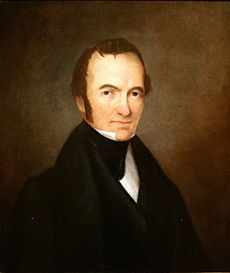

Because of this, the new Mexican government quickly invited Americans to settle. Stephen F. Austin was one of the first. He was given land in Texas. When Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the government continued to invite Americans. They wanted to develop their northern provinces, which had few people.

Mexican Texas: 1821–1836

In the 1820s, Mexico allowed Stephen F. Austin to bring more American families to Texas. Thousands more colonists from the United States then moved into the region, many without permission. Many did not want to be ruled by Mexico.

In 1829, Mexico ended slavery. Immigrants from the U.S. were sometimes allowed to keep slaves in some colonies. Or they found ways to avoid the law. Many slaves in Mexico were called "indentured servants" with the goal of becoming free later. Americans did not like this rule. They also did not like Mexico's government tightening its control. These disagreements eventually led to the Texas Revolution.

In 1821, José Francisco Ruiz made a truce with the Penatucka Comanche. This group was closest to the settlements in East and Central Texas. He then signed a peace treaty in Mexico City in December 1821. But within a year, the Mexican government did not give the gifts they promised. So, the Pentucka started raiding again.

By 1823, war was happening all along the Rio Grande. Most Mexican settlements were destroyed. Only those in the upper Rio Grande were safe. Thousands of Mexican refugees fled there. The Comanche pushed out or killed most Europeans and Mexicans in the region, except for the American Texans. In 1824, the Tonkawa made a treaty with Austin. They promised to help him against the Comanche.

Mexico signed more treaties in 1826 and 1834. But each time, they failed to keep their promises. In earlier years, this would have led to Comanche raids toward Mexico City. But the presence of American militias stopped these attacks. This made the Mexicans slow to pay.

Comanche raids were about taking goods and captives. So, American communities were good targets. Even though Texan forces were stronger than earlier Mexican colonists, the speed and large numbers of Comanche raiders overwhelmed many early Texan settlers. For example, in 1826, Comanches raided and burned Green DeWitt's new town of Gonzales.

From 1821 to 1835, colonists struggled with Comanche raids. This was despite the creation of full-time militia ranger companies in 1823. The Tonkawa and Delaware Indians, who were enemies of the Comanche, allied with the new immigrants. They hoped to gain allies against their traditional enemies. The Comanche hated the Tonkawa.

By 1823, Austin saw the need for special forces to fight the Plains tribes, especially the Comanche. The Comanche did not care if people were Mexican or American when they raided. Austin created the first Rangers by hiring 10 men. They were paid to fight Indians and protect the settlements. Soon, more Ranger companies were formed.

After Texas became a republic, this continued. Texas did not have money for a large army. So, they created small Ranger companies. These Rangers rode fast horses to chase and fight Comanches on their own terms.

The Fort Parker Attack

On May 19, 1836, a large group of Comanche, Kiowa, Wichita, and Delaware attacked Fort Parker. This outpost was finished in March 1834. Settlers thought it would protect them from Native Americans who had signed peace treaties. But these Native American groups were under Comanche influence, so the Comanche did not feel bound by the treaties.

The attack at Fort Parker resulted in the killing of settlers. The Comanche also took two women and three children captive. The Parker family was well known. The destruction of most of their family shocked all of Texas.

Survivors, like James W. Parker, called for revenge and help to get the captives back. This happened near the end of the Texas Revolution. Texans had just won the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836. Most Texans were busy returning home and dealing with their own losses.

Republic of Texas: 1836–1845

The time of the Republic of Texas and its relationship with Native Americans can be seen in three parts. First, President Sam Houston used diplomacy. Then, President Mirabeau B. Lamar was hostile. Finally, Houston returned for a second term and tried diplomacy again.

Houston led the republic to talk with the Comanche. They said they would stop raiding if they received gifts, trade, and regular face-to-face meetings. Houston was well-liked by Native Americans. He had married a woman of Cherokee descent. He had lived in Indian Territory for years and learned about their cultures.

Houston was willing to meet the Comanche on their terms. He believed it was worth spending money on gifts. The republic could not afford a large army to defend itself. It might not be able to defeat the Comanche-Kiowa alliance, especially if Mexico helped them.

Texans were upset by stories of thousands of children and women still being held captive. They demanded that the republic fight back against the Comanche. Under Lamar, the Republic of Texas fought the Comanche. They invaded Comancheria, burned villages, and attacked many war groups. But this effort made the new republic go broke.

More importantly, Texas forces rescued many hostages, but thousands remained captive. Houston was elected for his second term largely because Lamar's Native American policies had failed.

Houston's First Term: 1836–1838

Houston's first goal as president was to keep the Republic of Texas independent. He did not have the money to fight a big war against the Plains Indians. Houston had spent much of his childhood with the Cherokee Indians in Tennessee. He was friends with Cherokee Chief Bowles. Bowles later led a group of Cherokee who moved to Texas to escape being forced out of the Southeastern United States.

Houston supported a "Solemn Declaration." This gave the Cherokee rights to the land in Texas where they lived. He signed a treaty with the Cherokee and other tribes on February 23, 1836. This was the first treaty made by the Republic of Texas. It was signed by allied tribes like the Shawnee, Delaware, and Kickapoo.

The treaty gave these tribes land in areas that are now Smith and Cherokee counties. It also included parts of Van Zandt, Rusk, and Gregg counties. The treaty said that this land could not be sold or leased to anyone who was not a tribe member. After signing, Houston gave Chief Bowles a sword, a red silk vest, and a sash.

One of Houston's first actions as president was to send the treaty to the Texas Senate for approval. The treaty was delayed for a year. Lawmakers then decided it would harm Texans. This was because settler David G. Burnet already had land within the Cherokee treaty area. The treaty was declared "null and void" on December 26, 1837.

Houston tried to restore the treaty's terms throughout his presidency. He asked General Thomas J. Rusk to mark the boundary. But he was not successful before his presidency ended.

During Houston's first term, the Texas Rangers fought the Battle of Stone Houses against the Kichai on November 10, 1837. The Rangers were outnumbered and lost.

The Córdova Rebellion showed the Native American problems of Houston's first term. There was evidence of a plot by Cherokee Indians and Mexicans to rebel against Texas and rejoin Mexico. Houston did not believe his Cherokee friends were involved. He refused to arrest them. He used them to find the anti-Texans among the group, and those Mexicans were killed.

The Cordova Rebellion showed Houston's skill in stopping trouble without much bloodshed. When Houston left office, Texans were at peace with Native Americans. But many captives were still held by the tribes.

The Texas Congress passed laws opening all Native American lands to white settlement. They ignored Houston's veto. Settlements quickly moved north along the Brazos, Colorado, and Guadalupe rivers. This pushed into Comanche hunting grounds and the edges of Comancheria. As a result, the relationship between Texans and Comanches became violent.

Houston tried to restore peace. The Comanches were worried about the speed of Texan settlement. They considered a fixed boundary, which was new for them. However, Texas law did not allow Houston to give up any land claimed by the Republic. Still, he made peace with the Comanche in 1838.

Lamar's Presidency: 1838–1841

Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar, the second president of Texas, was unfriendly toward Native Americans. Lamar's team boasted they would remove Houston's "pet" Indians. In 1839, Lamar stated his policy: "The white man and the red man cannot dwell in harmony together," he said, "Nature forbids it."

His answer to the 'Indian Problem' was to "fight a harsh war against them." He wanted to chase them to their hiding places "without mercy or pity." He aimed to make them feel that "fleeing from our borders without hope of return, is better than the pains of war."

Lamar was the first Texas official to try "removal." This meant forcing Native American tribes to move to places far from white settlers. His policy aimed to create a permanent Native American border. Beyond this line, the "removed" tribes could live freely without white settlement or attacks. Lamar became convinced that the Cherokee could not stay in Texas. This was after their part in the 1838-39 Córdova Rebellion and the 1838 Killough massacre.

The Cherokee War

The Cherokee War and the removal of the Cherokee from Texas began soon after Lamar took office. Lamar demanded that the Cherokee give up their lands and property. They had been promised land if they stayed neutral during the Texas War of Independence. Lamar wanted them to move to the Indian Territory of the United States.

Houston had promised the Cherokee their land titles during the Córdova Rebellion. He protested Lamar's actions but it was no use. In May 1839, Lamar's government found a letter. It showed plans by Mexican officials to get Native Americans to fight against Texas settlers. With public support, Lamar decided to force the Cherokee Indians out of East Texas. When they refused, he used military force.

On July 12, 1839, the militia sent a peace group to negotiate their removal. The Cherokee reluctantly agreed to sign a treaty. It promised them money for their crops and the cost of moving. For the next 48 hours, the Cherokee said they would leave peacefully. But they refused to sign the treaty. This was because it said they had to be escorted out of Texas by armed guards.

On July 15, 1839, the commissioners told the Native Americans that Texans would march on their village immediately. Those willing to leave peacefully should fly a white flag. On July 15-16, 1839, a combined militia force attacked the Cherokees, Delaware, and Shawnee. This happened under Chief Bowles at the Battle of the Neches.

The Native Americans tried to fight at the village, but failed. They tried to regroup, but that also failed. About 100 Native Americans were killed, including Chief Bowles. Only three militia members died. Chief Bowles was carrying the sword Houston had given him when he was killed. After the battle, the Cherokee fled to the Choctaw Nation and northern Mexico. This left East Texas almost free of organized Native American communities. Their lands, once guaranteed by treaty, were given to American settlers.

Lamar and the Plains Tribes

Lamar's success in removing the Cherokee, a neutral tribe, from Texas made him bolder. He wanted to do the same with the Plains tribes. Lamar needed an army for his Native American policies. He began building one, which was very expensive.

At independence, Texas had about 30,000 American and Hispanic residents. The Cherokee had less than 2,000 people in Texas. So, removing them was not a huge drain on the republic. The Cherokee War was also relatively short and had few Texan casualties.

However, the Comanche and Kiowa had a population of 20,000 to 30,000 in the 1830s. They had many good firearms and horses. By the 1830s, the Comanche had a large network of Native American allies and a vast trading system. Texas had a militia but no standing army. Its small navy had been reduced. Lamar had neither the people nor the money for his policy after the Cherokee War, but he did not give up.

Lamar's time as president saw more violence between the Comanche and colonists. There were not enough Rangers to fight the Comanche in places like Palo Duro Canyon. At the end of 1839, some Comanche chiefs of the Penateka band believed they could not completely drive the colonists away. Attacks by the Cheyenne and Arapaho on their northern border, plus many deaths from smallpox, made the Penateka chiefs think a treaty might be best.

They also realized how important the captive Texans were to the Texans. So, they thought they could get big deals from the Texans. The Comanche offered to meet with Texans to make peace. They wanted a recognized border between Texas and Comancheria and the return of hostages. The famous Penateka war chief Potsʉnakwahipʉ ("Buffalo Hump") disagreed. He did not trust Lamar. None of the other 11 Comanche bands were involved in these peace talks.

The decision of chiefs from one Comanche band to talk, and their offer to return hostages, made Lamar believe the Comanche were ready to give up the hostages. However, most past talks about returning hostages were not honored by the Comanche. They got deals but did not return the hostages, or they delayed it forever.

Secretary of War Albert Sidney Johnston gave clear instructions. Lamar expected the Comanche to return the hostages in good faith. He also expected them to give in to his threats. Johnston sent militia to San Antonio with specific orders: "Should the Comanche come in without bringing with them the Prisoners, as it is understood they have agreed to do, you will detain them. Some of their number will be dispatched as messengers to the tribe to inform them that those detained, will be held as hostages until the Prisoners are delivered up, then the hostages will be released."

The Council House Fight

Thirty-three Penateka chiefs and warriors, along with 32 other Comanches, arrived in San Antonio on March 19, 1840. They came to meet with Texas officials. Texas officials demanded the return of all captives held by the Penateka. They also insisted that the Comanches leave Central Texas, stop bothering Texan settlements, stop working with Mexicans, and avoid all white settlements.

The main Penateka chief, Mukwooru ("Spirit Talker"), led the group. The Comanche chiefs brought one white captive, Matilda Lockhart, and several captured Mexican children. The talks happened at the council house. This was a stone building next to the jail. During the meeting, the Comanche warriors sat on the floor, as was their custom. The Texans sat on chairs on a raised platform facing them.

Matilda Lockhart had told them she saw 15 other prisoners at the main Comanche camp a few days before. She said the Native Americans wanted to see how much they could get for her. Then they planned to bring in the other captives one by one. The Texans demanded to know where the other captives were.

Mukwooru replied that different Comanche groups held the other prisoners. He said he thought the other captives could be ransomed. But it would be for a lot of supplies, like ammunition and blankets. He then ended his speech by saying, "how do you like that answer?"

The Texan militia entered the room and stood along the walls. When the Comanches would not, or could not, promise to return all captives right away, Texas officials said the chiefs would be held hostage until the white captives were freed.

The interpreter warned the Texan officials that if he gave that message, the Comanches would try to fight their way out. He was told to give the warning and left the room after translating. After learning they were hostages, the Comanches tried to fight their way out using arrows and knives. Texan soldiers fired at close range, killing both Native Americans and whites.

Comanche women and children waiting outside started firing arrows when they heard the noise inside. At least one Texan observer was killed. When a few warriors got out of the council house, all the Comanche started to run. The soldiers who followed kept firing, killing and wounding both Comanche and Texans.

Armed citizens joined the fight. They claimed they could not tell the difference between warriors, women, and children. So, they shot at all the Comanche. According to Anderson, this "confusion" was convenient for the Texans. It gave them an excuse to kill women and children.

According to a report by Col. Hugh McLeod on March 20, 1840, out of 65 Comanches, 35 were killed (30 adult men, 3 women, and 2 children). 29 were taken prisoner (27 women and children, and 2 old men). One Mexican escaped unnoticed. Seven Texans died, including a judge, a sheriff, and an army lieutenant. 10 more were wounded.

The Great Raid and Plum Creek Battle

To get revenge for the killing of 33 Comanche chiefs at the Council House Fight, almost all the remaining captives held by the Native Americans were killed. Only three were spared because they had been adopted into the tribe. Potsʉnakwahipʉ ("Buffalo Hump") wanted more revenge. He gathered his warriors and sent messages to all Comanche groups, and to the Kiowa and Kiowa Apache.

Most or all Comanche chiefs joined the raid. Buffalo Hump led about 500 warriors and 400 women and boys. They raided from the Edwards Plateau all the way to the coast. They burned and looted Victoria and Linnville. Linnville was the second-biggest port in Texas then. The Comanches took thousands of horses and mules. They also took a lot of valuable goods from the Linnville warehouses.

The people of Linnville wisely fled to the Gulf waters. They watched helplessly as the Comanche looted and burned the town. At Plum Creek near Lockhart, the Rangers and militia caught up to the Comanche. Several hundred militia led by Mathew Caldwell and Ed Burleson, plus all Ranger companies and their Tonkawa allies, fought the war party.

The Rangers and militia overcame the Comanche guarding their loot. In a running gunfight, they rescued several dozen captives. They also recovered mules carrying hundreds of thousands of dollars in gold.

The rest of Lamar's presidency involved brave but tiring raids and rescue attempts. They managed to get back several dozen more captives. Buffalo Hump continued his war against the Texans. Lamar hoped for another big battle to use his Rangers and militia to remove the Plains tribes.

However, the Comanche had learned from Plum Creek. They did not plan to gather in large numbers again. They did not want the militia to use cannons and massed rifle fire on them. Lamar spent $2.5 million fighting the Comanche in 1840. This was more than the Republic's total income during Lamar's two-year term.

Houston's Second Presidency: 1841–1844

When Sam Houston left the presidency the first time, people seemed to support Lamar's strong anti-Native American policies. But after the Great Raid and hundreds of smaller raids, with the Republic bankrupt and all captives either rescued or killed, Texans turned away from war. They elected Houston for his second presidency, hoping for more diplomacy.

Houston's Native American policy was to get rid of most regular Army troops. But he formed four new Ranger companies to patrol the frontier. Houston ordered the Rangers to protect Native American lands from settlers and illegal traders. Houston wanted to stop the cycle of anger and revenge that had gotten out of control under Lamar.

Under Houston, Texas Rangers were allowed to punish Native Americans severely for breaking rules. But they were never to start conflicts. If problems happened on either side, troops were ordered to find and punish the actual people responsible. They were not to get revenge on innocent Native Americans just because they were Native Americans.

Houston began to negotiate with the Native Americans. The Caddos were the first to respond. A treaty was made in August 1842. Houston then extended it to all tribes except the Comanche, who still wanted war. In March 1843, Houston reached agreements with the Delaware, Wichitas, and other tribes.

At that point, Buffalo Hump, who trusted Houston, began to talk. In August 1843, a temporary treaty led to a ceasefire between the Comanches and their allies, and the Texans. In October 1843, the Comanches agreed to meet Houston. They wanted to try to negotiate a treaty similar to the one at Fort Bird. (The fact that this included Potsʉnakwahipʉ "Buffalo Hump," after the Council House events, showed extraordinary Comanche trust in Houston.)

In early 1844, Buffalo Hump and other Comanche leaders, including Santa Anna and Old Owl, signed a treaty at Tehuacana Creek. They agreed to return all white captives and stop raiding Texan settlements. In return, the Texans would stop military action against the tribe. They would also set up more trading posts and recognize the border between Texas and Comanchería.

Comanche allies, including the Waco, Tawakoni, Kiowa, Kiowa Apache, and Wichita, also agreed to join the treaty. By the end of his second term, Houston had spent less than $250,000. He had brought peace to the frontier and a treaty between the Comanches and their allies. The Republic was only waiting for the United States to approve its statehood.

Jones's Presidency: 1845–1846

During the rest of the Republic of Texas period, President Anson Jones followed Houston's policies. However, Jones, like most Texas politicians, did not want to set a boundary for Comancheria. So, he supported those in the Legislature who stopped that part of the treaty.

Texas Becomes a State: 1845–1861

After the Texas Senate removed the boundary part from the treaty, Buffalo Hump rejected it. Fights started again. On February 28, 1845, the U.S. Congress passed a bill. It allowed the United States to annex the Republic of Texas. Texas became a U.S. state on December 29, 1845.

One main reason Texas wanted to join the U.S. was its huge debts. The United States agreed to take on these debts. In 1852, in return for this, Texas gave up a large part of its claimed territory. This land is now parts of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

Texas joining the United States marked the beginning of the end for the Plains Indians. The United States had the money and people to truly carry out a "removal" policy. And they did. In May 1846, Buffalo Hump realized he could not keep fighting the strong United States and Texas. So, he led the Comanche group to treaty talks at Council Springs. There, they signed a treaty with the United States.

As a war chief of the Penatucka Comanches, Buffalo Hump worked peacefully with American officials in the late 1840s and 1850s. He negotiated a non-government peace treaty with John O. Meusebach in 1847. In 1849, he guided John S. Ford's trip part of the way from San Antonio to El Paso. In 1856, he led his people to the new Comanche reservation on the Brazos River.

The Antelope Hills Expedition: 1858

The years 1856–58 were very violent on the Texas frontier. Settlers kept moving into Comancheria. 1858 saw the first Texan invasion into the heart of Comancheria. This was called the Antelope Hills expedition. It was led by Ford and included the Battle of Little Robe Creek.

This battle showed the beginning of the end for the Comanche as a strong people. They were successfully attacked deep in their own land. Valuable Native American hunting grounds were plowed over. Grazing land for Comanche horses was lost. The Comanche realized their homeland was being taken over by Texas settlers. The expedition showed the Comanches not on reservations that they could not expect protection there. So, they fought back with fierce raids into Texas.

By 1858, only five of the twelve Comanche bands still existed. One, the Penateka, had shrunk to only a few hundred on the reservation. Realizing their way of life was disappearing, the remaining free Comanche fought back with incredible violence.

The U.S. Army could not stop the violence. Federal troops were being moved out of the area for political reasons. At the same time, federal law and many treaties stopped state forces from going into federally protected Indian Territories. The U.S. Army was also told not to attack Native Americans in these territories.

The reason was that many tribes, like the Cherokee, were farming and living peacefully. Other tribes, like the Comanche and Kiowa, continued to live in Comancheria (part of the Indian Territories) while raiding white settlements in Texas.

The relationship between the federal government, Texas, and the native tribes was complex. This was because of a unique legal issue after Texas joined the U.S. The U.S. Constitution puts the federal government in charge of Native American affairs. It took over this role in Texas in 1846.

But when Texas joined the Union, the new state kept control of its public lands. In all other new states, the federal government controlled both public lands and Native American affairs. So, it could make treaties guaranteeing reservations. In Texas, however, the federal government could not do this. Texas strongly refused to give public land for Native American reservations within Texas. Meanwhile, it expected the federal government to pay for Native American affairs.

Federal Native American agents in Texas knew that land rights were key to peace. But Texas officials were uncooperative about Native American homelands. So, no peace was possible.

Aftermath of the Antelope Hills Expedition

The Battle of Little Robe Creek showed the Texan attitude toward women and children casualties in Native American fighting. Ford was accused of killing women and children in every battle against the Plains Indians. He dismissed it by saying it was hard to tell "warriors from squaws." But his dark jokes made it clear he did not care about the age or sex of his victims. Ford believed that the deaths of settlers, including women and children, during Native American raids, meant all Native Americans, regardless of age or sex, were combatants.

The Tonkawa warriors with the Rangers celebrated the victory. Other Native Americans never forgot the Tonkawa's alliance with Texan colonists. Despite pleas from the aging Placido to protect his people, the Tonkawa were moved from their reservation on the Brazos. They were put on a reservation in Oklahoma with the Delaware, Shawnee, and Caddo tribes.

In 1862, warriors from these tribes attacked the Tonkawas. 133 out of the remaining 309 Tonkawas were killed. The elderly Placido was among the dead. Today, fewer than 15 Tonkawa families remain on their reservation in Oklahoma.

Attack on Buffalo Hump's Camp

On October 1, 1858, Buffalo Hump's remaining Penateka Band was attacked. They were camped in the Wichita Mountains with other Comanche groups. United States troops led by Maj. Earl Van Dorn attacked them. Van Dorn allegedly did not know that Buffalo Hump's band had recently signed a peace treaty with the United States. Van Dorn and his men killed 80 Comanches.

This attack on a peaceful camp, where Native Americans had signed a peace treaty, was called a "battle" by Van Dorn. Some historians still call it the "Battle of Wichita Mountains." Despite this, an old and tired Buffalo Hump led his remaining followers to the Kiowa-Comanche reservation. This was near Fort Cobb in Indian Territory, Oklahoma. He was very sad about the end of the Comanches' traditional way of life. But he asked for a house and farmland to set an example for his people. He tried to live as a rancher and farmer. He died in 1870.

The Murder of Robert Neighbors: 1859

During this time, settlers began attacking Native Americans on reservations in Texas. Federal Native American agent Robert Neighbors became hated by white Texans. Neighbors claimed that U.S. Army officers at Fort Belknap and Camp Cooper did not give enough support to him and his agents. They also did not protect the Native Americans enough.

Despite constant threats to his life, Neighbors never stopped trying to do his duty and protect the Native Americans. With the help of federal troops, whom he finally shamed into helping him, he managed to keep white people away from the reservations.

However, he was convinced that Native Americans would never be safe in Texas. So, he decided to move them to safety in the Indian territories. In August 1859, he successfully moved the Native Americans without any deaths to a new reservation. He had to return to Texas for business. He stopped at a village near Fort Belknap. On September 14, 1859, while talking with a settler, a man named Edward Cornett shot and killed him. Historians believe his murder was a direct result of his actions protecting the Comanche. Neighbors probably did not even know his killer. He was buried in the civilian cemetery at Fort Belknap.

The Battle of Pease River: 1860

There are two different stories about what happened on Mule Creek on December 18, 1860. This was near Margaret, Texas, in Foard County. The official story is that Sul Ross and his forces surprised the Quahadi Band of the Comanche. They wiped them out, including their leader Peta Nocona.

According to Peta Nocona's son, Quanah Parker, his father was not there that day. He said the Comanches killed were almost all women and children in a camp where they were drying buffalo hides and curing meat. However, everyone agrees that at sunrise on December 18, 1860, Rangers and militia led by Sul Ross found and surprised a group of Comanche. They were camped on Mule Creek, a small river that flows into the Pease River. Almost everyone was killed. This included a brave warrior named Nobah, who died trying to protect his chief's wife and daughter.

Only one woman was allowed to live because she was recognized as white. She was later found to be Cynthia Ann Parker. The only other known survivors were a 10-year-old boy saved by Sul Ross and Cynthia Parker's baby daughter, "Prairie Flower."

Cynthia Ann Parker was returned to her white family. They watched her closely to stop her from going back to her husband and children. After her daughter died from the flu, she stopped eating and died. This happened because her guardians would not let her return to the Comanche to find her lost sons.

Civil War: 1861–1865

The Civil War brought much fighting and disorder to the plains. Cavalry troops left Indian Territory for other battles. Many Rangers joined the Confederate Army. The Comanche and other Plains tribes began to push back settlements from Comancheria. The frontier was pushed back over 100 miles. The Texas plains were filled with abandoned and burned farms. However, the Native American population was not large enough to take back control of all of Comancheria.

The Elm Creek Raid

In late fall of 1864, in Young County, Texas, a large group of 500 to 1,000 Comanche and Kiowa warriors raided. They were led by Kotsoteka chief Kuhtsu-tiesuat ("Little Buffalo"). They attacked the middle Brazos River country. They destroyed 11 farms along Elm Creek. They stole almost every cow, horse, and mule. They also surrounded Fort Murrah, a settler stronghold.

The home guard managed to hold the fort. After Kuhtsu-tiesuat died in the fight, the war party returned north with 10 women and children captives. A black scout named Britt Johnson, whose wife was among the captured women, went to look for the prisoners. He managed to rescue all of them with help from the friendly Penateka chief Asa-havey. Asa-havey later became known for this kind of rescue work.

First Battle of Adobe Walls

The first battle of Adobe Walls happened on November 26, 1864. It was near the ruins of William Bent's old trading post and saloon. This was near the Canadian River in Hutchinson County, Texas. This battle was one of the largest fights between whites and Native Americans on the Great Plains.

It happened because General James Henry Carleton, commander of the military in New Mexico, wanted to punish Comanche and Kiowa attacks. These tribes were attacking Santa Fe wagon trains. The Native Americans saw the wagon trains as invaders who killed buffalo and other game they needed to survive.

Colonel Kit Carson was put in charge of the First Cavalry, New Mexico Volunteers. He was told to campaign against the winter camps of the Comanches and Kiowas. These camps were said to be on the south side of the Canadian River. On November 10, 1864, Carson left Fort Bascom with 335 cavalry. He also had 75 Ute and Jicarilla Apache Scouts.

On November 12, Carson's force moved down the Canadian River into the Texas Panhandle. They had two howitzers, 27 wagons, an ambulance, and 45 days of food. Carson decided to go to Adobe Walls first, which he knew from working there years before. Bad weather, including an early snowstorm, made progress slow. On November 25, the First Cavalry reached Mule Springs, about 30 miles west of Adobe Walls.

Scouts reported a large Native American camp at Adobe Walls. Carson ordered his cavalry forward, followed by the wagons and howitzers. About two hours after sunrise on November 26, Carson's cavalry attacked a Kiowa village of 150 lodges. Chief Dohäsan and his people fled. They warned allied Comanche villages nearby. Guipago, a young war chief, managed to hold back the enemy.

Carson dug in at Adobe Walls around 10 am. He used a corner of the ruins as a hospital. Carson was surprised to find many villages in the area. There was a very large Comanche village, with 3,000–5,000 Native Americans in total. This was far more opposition than Carson expected.

The Kiowa led the first attack. Dohäsan was helped by Satank (Sitting Bear), Guipago, and Satanta. Guipago led the warriors in the first counterattack to protect the fleeing women and children. Satanta was said to have copied bugle calls back to Carson's bugler, confusing their signals.

Running low on supplies, Carson ordered his forces to retreat in the afternoon. The Native Americans tried to block his retreat by setting fire to the grass and brush near the river. Carson set back-fires and moved to higher ground. There, the two howitzers continued to hold off the Native Americans. When evening came, Carson ordered some of his scouts to burn the lodges of the first village. The Kiowa-Apache chief Iron Shirt was killed when he refused to leave his tepee. The army called Carson's mission a victory, even though he was forced to leave the field.

Battle of Dove Creek

On January 18, 1865, Confederate Texans attacked a peaceful tribe of Kickapoos at Battle of Dove Creek, in Tom Green County. The Texans were soundly defeated.

Final Years: 1865–1875

Native American Attacks on Cowboys

After the Civil War, Texas' growing cattle industry started to recover. Beef became very valuable after the war. Supplies from Texas were shipped to other states for high prices. Texas Longhorn cattle were in demand. The state's open range became their new home and breeding ground.

Hundreds of ranches and farms appeared by the end of the war. Veterans were hired as cowboys to protect cattle. However, moving the cattle was dangerous for the new ranches. The best routes for cattle drives went right through Comanche territory.

Relationships between them were sometimes peaceful. Cowboys could cross if they paid a fee. But during conflicts or when food was scarce, Native Americans would attack cowboys and their cattle. One sad case happened to a black cowboy named Britton Johnson in 1864. His ranch was raided by Comanches. They killed his son and kidnapped his wife and daughter. Johnson managed to negotiate for his family, but the Comanches did not leave him alone. A group of 25 warriors attacked Johnson again with two of his cowboys during a cattle drive. All of them died fighting.

Another well-known attack happened in the spring of 1867. Ranchers Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, with their cowboys, tried to drive their cattle around Comancheria. This trail is now known as the Goodnight–Loving Trail. During the journey, Loving had to scout ahead alone. This proved deadly. Loving and his ranch hand were soon attacked by 200 armed Comanche warriors patrolling the border. Loving made his last stand in the Pecos River to let his cowboy get help. Loving escaped the attack but was badly wounded and died soon after. Goodnight also faced raids. He was once wounded during an attack with another cowboy.

These attacks hurt the booming Texas economy. By the end of the 1860s, the Comanches had driven much of the cattle business out of West Texas. However, over the years, Comanches would surrender or sell their lands to Texas cattlemen.

Battle of Antelope Hills (1868)

On December 19, 1868, a large Comanche and Kiowa group met a company of the 10th Cavalry. This was on the way from Fort Arbuckle to Fort Cobb. On December 25, six companies of the 6th Cavalry and one company of the 37th Infantry arrived. They were on their way from Fort Bascom (New Mexico) to the Antelope Hills. They found the Nokoni village (about 60 tipis) of Kiyou (Horseback) and Tahka ("Arrowpoint").

Seeing the soldiers, Tahka, the war chief, led the Comanche warriors in a charge. But he was killed. The village and its supplies were destroyed. Kiowa warriors led by Manyi-ten came to join the fight. Only one soldier was killed. In December 1868, tired from lack of food and freezing weather, the Nokoni went to Fort Cobb and surrendered.

The Warren Wagon Train Attack

Henry Warren was hired to transport supplies to forts in West Texas. These included Fort Richardson, Fort Griffin, and Fort Concho. On May 18, 1871, his wagon train was traveling down the Jacksboro-Belknap road. They were heading towards Salt Creek Crossing. They met General William Tecumseh Sherman.

Less than an hour later, the teamsters saw a large group of riders ahead. Hidden in a thicket of bushes, the Kiowa had watched Sherman's inspection group pass without attacking. The night before, Mamanti ("He Walking-above"), a powerful shaman, had predicted that this small group would be followed by a larger one with more goods to take.

Three hours later, 10 mule-drawn wagons full of army corn and fodder reached the spot. As the warriors charged, the supply train quickly formed a circle. All the mules were put in the center. But the defenders were overwhelmed. The warriors destroyed the corn supplies, killing seven wagon drivers.

The Kiowa warriors lost three of their own. But they left with 40 mules heavily loaded with supplies. Five white men escaped. One was Thomas Brazeale, who reached Fort Richardson on foot, about 20 miles away. As soon as Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie learned of the incident, he told Sherman. Sherman and Mackenzie searched for the warriors responsible for the raid. The ambush had been planned by a large group of Kiowa warriors led by Satanta.

Satanta boasted about his actions. He said that Satank and Ado-ete were also involved. Sherman ordered their capture. They were arrested at Fort Sill. Sherman ordered their trial. This made them the first Native American leaders to be tried for raids in a U.S. court.

Sherman ordered the three Kiowa chiefs taken to Jacksboro, Texas, to stand trial for murder. Satank tried to escape. He was killed while traveling to Fort Richardson for trial. He began singing his death song and managed to grab a rifle from one of his guards. He was shot to death before he could fire. His body lay unburied in the road. His people were afraid to claim it, though Mackenzie said they could safely claim Satank's remains.

When General Sherman decided to send the Kiowa war chiefs to Jacksboro for trial, he wanted to make an example. What he did not want, but what happened, was that the trial became a big public event. First, the two lawyers appointed to represent the two Kiowa actually defended them. They did not just participate in a civics lesson as the Army wanted. Their strategy was to argue that the two chiefs were simply fighting a war for their people's survival. This attracted worldwide attention. It also created opposition to the whole process.

Also, the Bureau of Indian Affairs opposed the whole process. They argued that the two chiefs were not subject to civilian law. This was because their people were at war with the United States. The Native Americans were not sorry. At his trial, Satanta warned what might happen if he was killed: "I am a great chief among my people. If you kill me, it will be like a spark on the prairie. It will make a big fire – a terrible fire!"

Satanta was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, as was Big Tree. But Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis, under great pressure from leaders of the Quaker Peace Policy, decided to change the court's decision. The punishment for both was changed to life imprisonment. Thanks to the strong actions of Guipago, who threatened a new bloody war, Satanta and Big Tree were freed after two years. They had been imprisoned at the Huntsville State Penitentiary in Texas.

Battle of the North Fork of the Red River

In 1872, the Quaker Peace Policy had partly failed. It had greatly reduced battles between tribes and the U.S. military, but not entirely. Troops from Fort Sill could not officially be sent against the Comanche. However, some army officers were eager to attack the Comanche in the heart of Comancheria.

A captured comanchero (a trader with the Comanche), Edwardo Ortiz, told the army that the Comanches were on their winter hunting grounds. This was along the Red River on the Staked Plains. General Christopher C. Augur, commander of the Department of Texas, sent a group from Fort Concho. This group, led by Captain Napoleon Bonaparte McLaughlin, went on a two-month scouting trip in spring 1872. He returned to the fort, confirming that the main Comanche force was in camps on the Staked Plains. Ortiz also claimed that army groups could move well in that country. General Augur then called Mackenzie to San Antonio for a meeting. From this meeting, the army planned a campaign against the Comanche in their strongholds on the Staked Plains.

On September 28, near McClellan Creek in Gray County, Texas, the 4th U.S. Cavalry attacked a village of Kotsoteka Comanche. The battle was a surprise attack on the village. 23 men, women, and children were killed. 120 or 130 women and children were captured, along with more than 1,000 horses. Most of the villagers were captured. But Quahadi Comanche warriors arrived from a nearby village. Led by Quanah, they made the soldiers retreat quickly.

The next day, September 29, the Kotsoteka and Quahadi warriors attacked the military camp. They got their horses back but not their women and children. So, the Comanche prisoners were kept under guard. They were transferred to Fort Concho, where they were held through the winter. Mackenzie used the captives to force the Native Americans not on reservations back to them. He also forced them to free white captives.

Mackenzie's plan worked. Soon after the battle, Mow-way and Parra-ocoom moved their groups near the Wichita Agency. Nokoni chief Horseback, who had family members among the prisoners, helped persuade the Comanches. They traded stolen livestock and white captives, including Clinton Smith, for their own women and children.

This was the first time the United States had successfully attacked the Comanches in the heart of Comancheria. It showed that if the Army wanted to force the Comanches onto reservations, the way to do it was to destroy their villages. This would leave them unable to survive off the reservation.

The Red River War

On July 20, 1874, General Sherman ordered General Philip Sheridan to begin an attack against the Kiowa and Comanches on the plains of West Texas and Oklahoma. The goal was to kill them or drive them to reservations. The army used Mackenzie's tactics from the 1872 campaign at North Fork. They would attack the Comanche in their winter strongholds. They would destroy their villages and their ability to live independently.

During the summer of 1874, the Army launched a campaign. It aimed to remove the Comanche, Kiowa, Kiowa Apache, and Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes from the Southern Plains. This campaign was meant to force them onto reservations in Indian Territory. The campaigns of 1874 were different from earlier attempts to bring peace to the frontier.

The "Red River War," as it was called, ended the culture and way of life for the Southern Plains tribes. It brought an end to the Plains tribes as a distinct people. The Red River War happened when buffalo hunters were killing the great American Bison almost to extinction. Both the bison and the people who depended on them nearly disappeared at the same time.

There were about 20 battles between Army units and the Plains Indians during the Red River War. The well-equipped and well-supplied Army simply kept the Native Americans moving. In the end, they ran out of food, ammunition, and the ability to fight any longer.

Second Battle of Adobe Walls

The Second Battle of Adobe Walls happened during the Red River War. The Plains tribes realized, with growing desperation, that buffalo hunters were killing off their food supply. This threatened their very survival. A combined force of Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and other Plains tribes gathered almost 700 warriors. They tried to attack the buffalo hunters camped at the old ruins at Adobe Walls.

On June 27, 1874, the allied Native American force attacked the 28 hunters and one woman camped at Adobe Walls. If the defenders had been asleep, as the attackers hoped, they would have been quickly defeated and killed. But the defenders were awake. Their long-range buffalo guns made the attack useless. With Quanah Parker wounded, the Native Americans gave up the attack. It was the last major attempt by the Native Americans to defend the Plains. The difference in weapons was simply too great to overcome.

Army Attack Near Anadarko

After Adobe Walls, several groups went to the Fort Sill agency for the census and to receive payments. But only Isa-nanica was allowed to stay on the Fort Sill reserve. The other chiefs had to lead their people to the Wichita agency at Anadarko. After some killings by the Kiowa, the 25th Infantry was sent to guard Anadarko. They were joined by four companies of the 10th Cavalry from Fort Sill.

On August 22, 1874, near Anadarko, a cavalry group was sent to Pearua-akup-akup's village. They demanded all their weapons. When the Nokoni warriors fought back, the soldiers fired on them. Guipago, Satanta, Manyi-ten, and Ado'ete came with their Kiowa warriors. The remaining companies of the 10th Cavalry also came. They faced 200 or 300 Nokoni Comanche and Kiowa.

During the night, the Comanche tents and supplies were burned. The next day, August 23, the fight continued. Four Army soldiers and 14 warriors were wounded (one warrior died). The Nokoni and Kiowa then retreated. They burned the prairie and killed some white men near Anadarko and along Beaver Creek. Friendly Tosawi and Asa-havey led the Penateka to Fort Sill. Kiyou probably decided it was wiser to go, with his friendly Nokoni band, to the Wichita agency. The Yamparika and Nokoni joined the Quahadi and Kotsoteka. They camped at Chinaberry Trees, Palo Duro Canyon.

Satanta's Final Years

Satanta was released in 1873 (and Ado'ete was also released). He was said to have soon returned to attacking buffalo hunters and was present at the raid on Adobe Walls. His presence at the battle broke his parole. The government ordered his arrest. He surrendered in October 1874 and was sent back to the state prison.

In his book "History of Texas," Clarance Wharton writes about Satanta in prison: "After he was returned to the penitentiary in 1874, he saw no hope of escape. For a while he worked on a chain gang which helped to build the M.K. & T. Railway. He became sullen and broken in spirit, and would be seen for hours gazing through his prison bars toward the north, the hunting grounds of his people."

Satanta died on October 11, 1878. Ado'ete was also arrested again. But unlike Satanta, he was not sent back to Huntsville. This was because it could not be proven that he was present at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. Both Satank and Satanta are buried at the Chief's Knoll at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

The Palo Duro Campaign

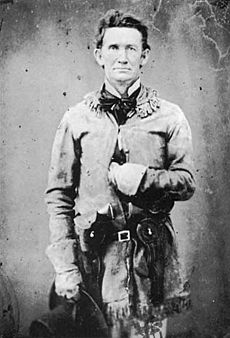

Colonel Mackenzie and the 4th Cavalry Regiment chased Quanah Parker and his followers through late 1874 into 1875. He led a five-group movement to meet at the Native American hiding places along the eastern edge of the Staked Plains.

Mackenzie fought a very brave and important battle on September 28, 1874. He destroyed five Native American villages in Palo Duro Canyon. He also destroyed 1,000 of their horses in Tule Canyon. This broke the Native Americans' ability to resist. He took their most prized possessions, their horses, and destroyed their homes and food supplies.

On November 5, 1874, Mackenzie's forces won a small battle, his last, with the Comanches. In March 1875, Mackenzie took command at Fort Sill. He also gained control over the Comanche-Kiowa and Cheyenne-Arapaho reservations.

Mackenzie sent Jacob J. Sturm, a doctor and interpreter, to negotiate Quanah's surrender. Sturm found Quanah, whom he called "a young man of much influence with his people." He explained why they should surrender peacefully. Mackenzie had promised that if Quanah surrendered, his entire group would be treated honorably. No one would be charged with any crime. (The arrest and trial of Kiowa leaders in 1871 had made this a real concern.)

However, Sturm also carried Mackenzie's personal promise. If the Quahada refused to surrender, every man, woman, and child would be hunted down and killed. Quanah later said he was ready to die. But he did not want to condemn the women and children to death. Quanah believed Colonel Mackenzie.

Quanah rode to a mesa. There, he saw a wolf come toward him, howl, and trot away to the northeast. Overhead, an eagle "glided lazily and then whipped his wings in the direction of Fort Sill," as Jacob Sturm reported later. Quanah saw this as a sign. On June 2, 1875, he led his group to Fort Sill and surrendered.

On that day, the Plains Indians' traditional way of life was completely destroyed. Quanah worked tirelessly to help his people adapt to the Anglo world that had defeated them. Mackenzie appointed him as the sole chief of the Comanches. He worked hard to bring education and the ability to survive in the white man's world to his people. He tried to keep his people's land together. When that became impossible, he tried to get the best deal for his people.

Kiyou was appointed as the Comanche head chief. He was ordered to choose the "worst" Comanche chiefs and warriors to be blamed for the uprising at Palo Duro. Nine Comanche and 27 Kiowa were sent to Fort Marion, Florida. All the main Comanche leaders (Quanah, Mow-way, Tababanika, Isa-rosa, Hitetetsi, Kobay-oburra) were kept safe. Guipago, Manyi-ten, Tsen-tainte, and Mamanti were sent to Fort Marion. Guipago was sent back to Fort Sill in 1879. He died of malaria in July 1879.

|

See also

In Spanish: Guerras indias de Texas para niños

In Spanish: Guerras indias de Texas para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |