Santa Fe Trail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Santa Fe Trail |

|

|---|---|

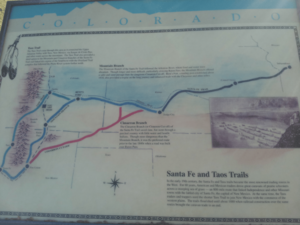

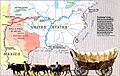

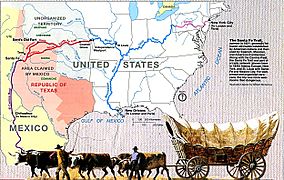

Map of the Santa Fe Trail

|

|

| Location | Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Colorado |

| Established | 1822 |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Santa Fe National Historic Trail |

The Santa Fe Trail was a famous path that connected Franklin, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was like a superhighway in the 1800s! A man named William Becknell first used it in 1821. For many years, it was a very important road for trading goods. People used it until 1880, when trains started going to Santa Fe. The trail also connected to another old road called El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which went all the way to Mexico City. Today, parts of the Santa Fe Trail are part of other roads like U.S. Route 66.

The trail went through the land of the Comanche people, called Comancheria. The Comanche knew the trail was important, so they asked for payment from traders who wanted to pass through. American traders also saw the Comanche as people they could trade with. The Comanche often raided areas further south in Mexico. This made New Mexico rely more on trade with Americans. The Comanche raided to get horses, which they could then sell. By the 1840s, so many people were using the trail that it affected the bison herds. The bison couldn't reach their usual feeding grounds. This, along with too much hunting, caused the bison population to drop a lot. When the Comanche lost their main source of food and trade (the bison), their power in the region became weaker.

In 1846, during the Mexican–American War, the United States Army used the Santa Fe Trail to move into New Mexico.

After the war, the U.S. gained control of the Southwest. The trail was very important for helping the U.S. develop and settle these new lands. It played a big part in the country's move westward. Today, the National Park Service remembers this historic road as the Santa Fe National Historic Trail. There's also a highway route that follows the trail's path. It goes through Kansas, southeastern Colorado, and northern New Mexico. This highway is called the Santa Fe Trail National Scenic Byway.

Contents

History of the Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail was first used by Native Americans and European traders in the late 1700s. Later, in the 1800s, many people from the United States used it. This happened after the U.S. bought the Louisiana Territory. Traders and settlers traveled across the southwest from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The main trading center in Missouri was St. Louis, which had a port on the Mississippi River.

In 1719, a French officer named Claude Charles Du Tisne tried to create a trade route to Santa Fe. His trip started in Kaskaskia, Illinois, but Native American tribes in Kansas stopped him. Later, French traders Pierre Antoine and Paul Mallet successfully traveled from Kaskaskia, Illinois, to Santa Fe and back in 1739-1740. They made other trips too, facing challenges from Native Americans and Spanish authorities. Then, the French explorer Pierre Vial made another important trip in 1792. French traders from St. Louis slowly became the main fur traders in Santa Fe and with the Native American tribes. Other French traders, like Auguste Pierre Chouteau and Jules de Mun, also traveled the trail in 1815. However, Spanish officials arrested them in Santa Fe.

After the U.S. bought Louisiana in 1803, Americans improved the Santa Fe Trail. They started using it more often in 1822. This was because Mexico had just become independent from Spain, creating new trade chances. Goods made in Missouri were taken to Santa Fe, which was then part of the Mexican state of Nuevo Mexico.

Settlers looking for free land used wagon trains to follow different emigrant trails. These trails branched off to places further west. The idea of manifest destiny was popular at the time. This was the belief that the U.S. should stretch from one coast to the other. The Santa Fe Trail connected cities along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers to western areas. It was used to carry products from the central plains to towns like St. Joseph and Independence, Missouri.

In the 1820s and 1830s, the trail was also used in the other direction. Traders used it to bring food and supplies to fur trappers and mountain men. These men were exploring and opening up the remote Northwest, including areas in Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Montana. A mule trail also went north to supply the valuable fur trade on the Pacific Coast.

Trade Connections

Santa Fe was close to the northern end of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. This road went overland from Mexico City to San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico.

Mule trains also carried goods from Fort Bernard in Wyoming to the Santa Fe Trail at Fort Bent in Colorado.

Santa Fe's Importance for Trade

In 1825, a merchant named Manuel Escudero from Chihuahua was asked by New Mexico's governor to talk with the U.S. government. His goal was to open U.S. borders for Mexican traders. Starting in 1826, important families from New Mexico, like the Chávezes and Oteros, began trading along the trail. By 1843, most of the traders on the Santa Fe Trail were from New Mexico and Chihuahua.

In 1835, Mexico City sent Albino Pérez to govern New Mexico. In 1837, people in northern New Mexico rebelled against Pérez. They were unhappy with new laws that taxed trade and entertainment. They also didn't like the large land grants given to wealthy Mexicans. New Mexicans valued their freedom on the frontier, far from Mexico City. The rebels defeated and killed Governor Albino Perez. However, forces from southern New Mexico, led by Manuel Armijo, later removed the rebels from power.

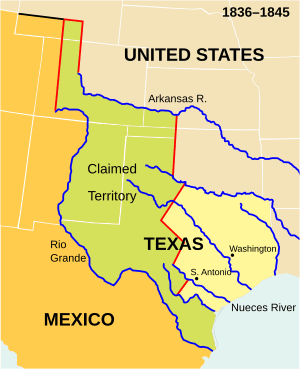

Texas and Mexico Disagree

The Republic of Texas and Mexico both claimed Santa Fe. This was part of the land north and east of the Rio Grande. Both nations claimed this area after Texas broke away from Mexico in 1836.

In 1841, a small group of soldiers and traders left Austin, Texas, for Santa Fe. They represented the Republic of Texas and its president, Mirabeau B. Lamar. They wanted to convince the people of Santa Fe and New Mexico to join Texas. They also wanted to control the Santa Fe Trail trade. Knowing about the recent problems in New Mexico, they hoped to be welcomed by the rebels. This trip, known as the Texan Santa Fe Expedition, faced many problems. Governor Armijo's Mexican army captured the group. They were treated very harshly during a difficult march to Mexico City. There, they were put on trial, found guilty, and sent to prison.

In 1842, Colonel William A. Christy asked Sam Houston, the president of Texas, for help with a plan to overthrow the governments in New Mexico and Chihuahua. He suggested giving half of what they gained to the Republic of Texas. Houston agreed, but only if the plan was kept very secret.

Houston made Warfield a colonel. Warfield tried to find volunteers in Texas, St. Louis, Missouri, and the southern Rocky Mountains. He recruited John McDaniel and a small group of men near St. Louis. Warfield gave McDaniel the rank of a Texas captain. After Warfield went towards the Rockies, McDaniel led a robbery in April 1843. This happened in what is now Rice County, Kansas. They robbed a trading group on the Santa Fe Trail that wasn't well protected. The leader of the group, Antonio José Chávez, was killed. He was the son of a former governor of New Mexico.

Warfield reportedly didn't know about the crime. McDaniel and one other person were tried, found guilty, and executed. Other people involved who were arrested by the U.S. were also found guilty and imprisoned. Newspapers reported that Americans and Mexicans were very angry about the crime. Local merchants and citizens at the U.S. end of the Santa Fe Trail demanded justice. They wanted the stable trade that their economy depended on to return.

After Chávez was killed, Warfield started some small fights in the area. He used people he had recruited from the southern Rockies. He attacked Mexican troops outside Mora, New Mexico, without being provoked, and five soldiers died. Warfield lost his horses after a fight in Wagon Mound, where Mexican forces had chased him. After Warfield's men reached Bent's Fort on foot, they broke up their group.

In February 1843, Colonel Jacob Snively was given a job to stop Mexican trading groups along the Santa Fe Trail. This was similar to what Warfield was asked to do the year before. After Warfield's volunteers broke up, he found and joined a group of 190 Texas soldiers called the "Battalion of Invincibles." This group was led by Snively. New Mexico Governor Manuel Armijo led Mexican troops out of Santa Fe to protect incoming trading groups. But, after the Invincibles destroyed much of an advance group led by Captain Ventura Lovato, the governor went back. After this battle, many Americans quit, and Snively's group became much smaller, with just over 100 men. Snively planned to rob Mexican merchant groups in land claimed by Texas. This was to get back at Texas for recent executions and Mexican invasions. However, U.S. troops who were protecting the trading groups quickly arrested and disarmed Snively's battalion. After taking their weapons, Captain Philip St. George Cooke allowed them to return to Texas.

The Santa Fe Trail and the Railroad

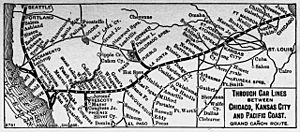

In 1863, even with arguments about railroad laws, business people started investing in the American Southwest. This led to the building of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. The name shows what the founders wanted: the eastern end was planned to be in Atchison, Kansas.

In Kansas, the AT&SF railroad tracks generally followed the Santa Fe Trail west of Topeka. This happened as the railroad grew between 1868 and 1874. When a railroad bridge was built across the Missouri River, it connected eastern markets to the cattle trail in Dodge City and coal mines in Colorado. This helped Kansas City, Missouri, grow a lot. Building the railway further west into New Mexico was delayed, and the new railroad struggled for money. To help themselves, the railway started offering "Shopping Excursion deals." These were trips for people who wanted to look at land to buy. The railroad gave discounts on these trips to visit its land offices. If someone bought land, the cost of the ticket was taken off the purchase price.

The railroad sold land that Congress had given it. This helped new towns and businesses grow along its route. This, in turn, created more train traffic and money for the railway. With this money, the railway expanded west, adding new connections through the tougher western parts of the Trail. As trains became more common, trade on the Santa Fe Trail itself soon became only local. In a way, after World War I, the trail was "reborn." By the 1920s, it slowly became paved roads for cars.

The Trail's Route

The eastern start of the trail was in the central Missouri town of Franklin. This town was on the north bank of the Missouri River. The path across Missouri that Becknell first used followed parts of the older Osage Trace and Medicine Trails. West of Franklin, the trail crossed the Missouri River near Arrow Rock. After that, it generally followed the route of today's U.S. Route 24. It went north of Marshall, through Lexington to Fort Osage, and then to Independence. Independence was also a starting point for the Oregon and California Trails.

West of Independence, the trail generally followed the route of today's U.S. Route 56. This went from near Olathe to the western border of Kansas. It then entered Colorado, cutting across the southeastern corner of the state before going into New Mexico. The part of the trail between Independence and Olathe was also used by people traveling on the California and Oregon Trails. These trails branched off to the northwest near Gardner, Kansas.

From Olathe, the trail went through towns like Baldwin City, Burlingame, and Council Grove. Then it swung west of McPherson to the town of Lyons. West of Lyons, the trail followed almost the same path as today's Highway 56 to Great Bend. You can still see ruts in the ground from the trail in several places. At Great Bend, the trail met the Arkansas River. Parts of the trail followed both sides of the river upstream to Dodge City and Garden City.

West of Garden City in southwestern Kansas, the trail split into two main paths. One path was called the Mountain Route or the Upper Crossing. It followed the Purgatoire River from La Junta upstream to Trinidad. Then it went south through the Raton Pass into New Mexico.

The other main path was called the Cimarron Cutoff or Cimarron Crossing. This path cut southwest across the Cimarron Desert. This desert was also known as the Waterscrape or La Jornada. It went to the valley of the Cimarron River near the towns of Ulysses and Elkhart. Then it continued towards Boise City, Oklahoma, to Clayton, New Mexico. This path joined up with the northern Mountain Route at Fort Union. This Cimarron route was usually very dangerous because it had very little water. The Cimarron River was one of the only water sources along this part of the trail.

From Watrous, the two reunited paths continued south to Santa Fe. Part of this route has been named a National Scenic Byway.

Challenges on the Trail

Travelers faced many difficulties along the Santa Fe Trail. The trail was about 900 miles (1,450 km) long. It went through dangerous plains, hot deserts, and steep, rocky mountains. The weather was extreme: very hot and dry summers, and long, very cold winters. Fresh water was hard to find, and the high plains had almost no trees. The Pecos, Arkansas, Cimarron, and Canadian rivers in the region could have very different amounts of water flowing through them each year.

Also, unlike the Oregon Trail, there was a serious risk of attacks from Native American tribes. Neither the Comanche nor the Apache tribes of the southern plains liked people crossing their land. In 1825, Congress voted to protect the Santa Fe Trail, even though much of it was in Mexican territory. Not having enough food and water also made the trail very risky. Bad weather, like huge lightning storms, made things even harder for travelers. If a storm hit, there was often no place to hide, and the animals could get scared. Rattlesnakes were also a threat, and many people died from snakebites. Later, the groups of wagons became larger to help prevent Native American raids. Travelers also used more oxen instead of mules. Oxen were better at pulling heavy loads, and Native Americans valued them less, so there was less risk of them being stolen.

Preserving the Trail's History

Parts of the Santa Fe Trail in Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In Missouri, this includes places like the 85th and Manchester "Three Trails" Trail Segment and the Arrow Rock Ferry Landing. The longest clear section of the trail, Santa Fe Trail Remains, near Dodge City, Kansas, is a National Historic Landmark. In Colorado, the Santa Fe Trail Mountain Route – Bent's New Fort is also on the National Register.

Notable Places Along the Trail

- Missouri

- Arrow Rock (Arrow Rock Landing, Santa Fe Spring, Huston Tavern)

- Harvey Spring/Weinrich Ruts

- Independence (Santa Fe trail Ruts, Lower Independence (Blue Mills) Landing, Upper Independence (Wayne City) Landing)

- Kansas City (Westport Landing)

- Kansas

- Kansas City (Shawnee Mission, Big Blue River Crossing)

- Council Grove (Kaw Mission, Neosho River Crossing, Hermit's Cave, Last Chance Store, Council Oak, Post Office Oak)

- Fort Larned National Historic Site

- Fort Dodge (Jackson's Grove and Island, Santa Fe Trail Ruts, Middle Crossing, Point of Rocks, Fort Atkinson Site)

Mountain Route towards Colorado

- Arkansas River Crossing

- Colorado

Mountain Route

Cimarron Route through Kansas towards Oklahoma

- New Mexico

Mountain Route

- Clifton House

- Cimarron (Aztec Mill, Cimarron Plaza and Well)

- Philmont Scout Ranch

Cimarron Route

Joint route

- Fort Union National Monument

- Pecos National Historical Park

- Santa Fe

- De Vargas Street House, Oldest House in the United States

- Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Area

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Camino de Santa Fe para niños

In Spanish: Camino de Santa Fe para niños

- MO: Jackson County Historic Places

- KS: Johnson County Historic Places

- OK: Cimarron County Historic Places

- NM: Colfax County Historic Places

- Oregon-California Trails Association

- Pawnee Rock

- Related National Park Units

- Santa Fe Trail Remains

- Santa Fe Trail Museum, part of the Trinidad History Museum

- Santa Fe Trail Historical Park in El Monte, California

- Trailside Center museum in Kansas City, Missouri

- Scenic byways in the United States

- Tree in the Trail

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |