Camino Real de Tierra Adentro facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Camino Real de Tierra Adentro |

|

|---|---|

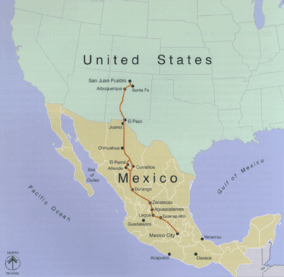

Map of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

|

|

| Location | Mexico and the United States |

| Governing body |

|

| Website | El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Location | Mexico |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iv) |

| Inscription | 6969 (4993rd Session) |

| Area | 3,101.91 ha (7,665.0 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 268,057.2 ha (662,384 acres) |

The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro means "Royal Road of the Interior Land" in English. It was a very long and important trade route. This historic road stretched about 2,560-kilometre (1,590 mi) (1,600 miles). It connected Mexico City all the way to San Juan Pueblo in New Mexico, USA.

People used this road from 1598 to 1882. It was the most northern of four main "royal roads." These roads linked Mexico City to other important places during the time Spain ruled the Americas.

In 2010, UNESCO added 55 sites along the Mexican part of the route to the World Heritage List. This included old cities, towns, bridges, and large farms called haciendas. This part of the route is about 1,400-kilometre (870 mi) (870 miles) long. It goes from the Historic Center of Mexico City to Valle de Allende, Chihuahua.

A 404-mile (650 km) (650 km) section of the road in the United States is called the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail. It became part of the National Historic Trail system in 2000. The National Park Service and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management help look after this historic route. They work with the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association (CARTA).

Contents

What Was the Route Like?

The Camino Real started in Mexico City near the main square, the Zócalo. It went north through places like San Miguel de Allende. The road ended near Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A Look Back: History of the Road

Before Europeans Arrived

Long before Europeans came, native tribes in Mexico used this route. They used it for hunting and trading. The path connected people from the Valley of Mexico to those in the north. They traded things like turquoise, obsidian, salt, and feathers. By the year 1000 AD, a busy trade network existed. It stretched from Mesoamerica all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

When Europeans Came

After the Spanish took over Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) in 1521, they explored new lands. They wanted to expand their empire and find more riches for Spain. They followed the trails that the native people already used for trading.

In 1598, a group of Spanish soldiers led by Juan de Oñate got lost in the desert. They were looking for the best way to the Rio Grande. A local native person they met drew a map in the sand. This map showed them the only safe way to the river. They reached the Río del Norte near El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. They then mapped and extended the route to Española. Oñate made Española the capital of the new province. This new trail became the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro. It was the most northern of the four main "royal roads" that connected Mexico City to its important areas.

After the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, the Spanish were forced out of New Mexico. But Spain decided not to give up the province. They kept a supply route open to help their people there. This system was called the conducta. It used wagon caravans that left Mexico City every three years. They traveled to Santa Fe along the Camino Real. The trip was long and hard, taking six months. This included two to three weeks of rest stops.

Travelers faced many dangers. Rivers could flood, making them wait for weeks. Long dry spells made water hard to find. The scariest part was crossing the Jornada del Muerto. This was a 100 kilometres (62 mi) (60-mile) stretch of desert with no water.

Besides needing supplies, the biggest danger was attacks. Groups of bandits robbed travelers in some areas. Further north, native groups like the Chichimecas often attacked. They mostly wanted horses, but sometimes took women and children. Spanish forts called presidios were built along the way. Soldiers from these forts helped protect the caravans. At night, in dangerous areas, wagons formed a circle. People and animals stayed safe inside the circle.

The Camino Real was used for over 300 years, from the mid-1500s to the 1800s. It was mainly used to transport silver from northern mines. Over time, the road got better, and dangers became fewer. More farms and towns grew up along the route.

The 1700s on the Trail

During the 1700s, many new places appeared along the Camino Real. The area between Durango and Santa Fe became known as "the Chihuahua Trail." The city of Chihuahua, founded in 1709, became a very important trading center.

Albuquerque, founded in 1706, also became a key stop. Because it was easy to defend, Albuquerque became the main trading center between New Mexico and the rest of New Spain. People traded cattle, wool, textiles, animal skins, salt, and nuts. This trade mostly happened with mining cities like Chihuahua and Parral.

Ciudad Juárez became another major stop. By 1765, it had over 2,600 people. This made it the largest city on the northern border of New Spain. Ciudad Juárez was known for its farms and ranches. They produced wines, brandy, vinegar, and raisins.

In the 1700s, the Spanish king allowed special markets called Fairs. These Fairs helped boost trade along the Camino Real. Important Fairs included those in San Juan de los Lagos, Saltillo, and Chihuahua. The Chihuahua Fair was very important for merchants from New Mexico. The Taos Fair was also a big yearly event. Here, Comanche and Ute tribes traded weapons, horses, and furs with the Spanish. Spain kept control over trade in its northern areas. This meant no trade happened with the French in Louisiana.

By the late 1700s, Spain wanted to protect its northern lands. Other European powers, especially England and France, wanted these lands. Spain tried to include native people in their society and economy. They wanted natives to help defend the Spanish border.

In 1786, Bernardo de Gálvez, the leader of New Spain, wrote down three ways to deal with native groups. These were:

- Keep military pressure on tribes that were hostile or not allied.

- Form alliances with friendly tribes.

- Encourage trade with natives who had peace treaties with Spain.

By the late 1700s, a shaky peace was made between the Spanish and Apache tribes. This led to a big increase in trade along the Camino Real. Products came from all over the world. This included goods from other parts of New Spain, Europe, and even from Asia. For example, merchants in Parral sold pottery from Michoacán, porcelain from China, and clay goods from Guadalajara.

The 1800s and the End of the Road

The 1800s brought many changes for Mexico. From the Napoleonic Wars to the start of the Mexican War of Independence, the government was unstable. It struggled to send supplies to the northern areas. This led to new ways of getting goods. In 1807, an American explorer named Zebulon Pike explored the border between the US and New Spain. He wanted to find a way for US trade to reach New Mexico. Spanish officials captured Pike in 1807. They sent him along the Camino Real to Chihuahua for questioning. While there, Pike learned about unhappiness with Spanish rule.

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain after 11 years of fighting. The Camino Real remained important during this time. Travelers used it to share news about the war with towns in the north. Both rebels and royal forces used the road. For example, after Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla started the war, he used the road to retreat. He was captured and executed by royal forces.

Between 1821 and 1822, after Mexico's independence, the Santa Fe Trail was created. This trail connected the US territory of Missouri with Santa Fe. At first, US merchants were arrested for bringing illegal goods into Mexico. But northern Mexico's growing money problems led to more tolerance for this trade. The Santa Fe Trail provided new markets for local products from New Mexico. By 1827, a profitable trade link was formed between Missouri, New Mexico, and Chihuahua.

In 1846, a disagreement over the Texas-Mexico border led to the Mexican–American War. US forces invaded Mexico. General Stephen W. Kearny used the Santa Fe Trail to take New Mexico's capital. Another force, led by Colonel Alexander William Doniphan, fought Mexican groups on the Camino Real. Doniphan's forces captured El Paso del Norte and later Chihuahua City. From 1846 to 1847, the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro was used constantly by American forces. They traveled deep into Mexico. Many American soldiers wrote in their journals about what they saw. They noted populations of cities and even prices of goods and animals.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in February 1848. Mexico gave up most of its northern lands to the US. This included parts of what are now New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, California, Nevada, and Utah. The Camino Real de Tierra Adentro was then split between two countries forever. Many of its stories have been lost, but its cultural importance remains today.

World Heritage Site Status

The Mexican part of the road was considered by UNESCO in 2001. They looked at it for its cultural importance. This meant it showed "creative genius" and "a great exchange of influences." In 2010, UNESCO also said it was important for showing "a significant stage of human history." Finally, on August 1, 2010, UNESCO officially named this road a World Heritage Site. This included 60 historical sites along the route.

UNESCO recognized 60 sites along the road. Five of these (Mexico City, Querétaro City, Guanajuato City, San Miguel de Allende, and Zacatecas) were already World Heritage Sites. The original historic route is not exactly the same as the UNESCO-recognized route. UNESCO left out some parts, like the section north of Valle de Allende in Chihuahua. They also left out the Hacienda de San Diego del Jaral de Berrio in Guanajuato. Because of this, there's a plan to add more parts to the World Heritage Site later. The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia is looking for more evidence of old bridges, pavements, and haciendas.

Recognized Sites in Mexico

Here are some of the places along the Camino Real that UNESCO has recognized:

Mexico City and State of Mexico

- Historic center of Mexico City.

- Old College of San Francisco Javier in Tepotzotlán.

- Aculco de Espinoza.

- Bridge of Atongo.

- Part of the Camino Real between Aculco de Espinoza and San Juan del Río.

State of Hidalgo

- Templo and exconvento de San Francisco in Tepeji del Río de Ocampo and its bridge.

- Part of the Camino Real between the bridge of La Colmena and the Hacienda de La Cañada.

State of Querétaro

- Historic center of San Juan del Río.

- Hacienda de Chichimequillas.

- Chapel of the hacienda de Buenavista.

- Historic center of Querétaro City.

State of Guanajuato

- Bridge of El Fraile.

- Antiguo Real Hospital de San Juan de Dios in San Miguel de Allende.

- Bridge of San Rafael in Guanajuato City.

- Bridge La Quemada.

- Sanctuario de Jesús Nazareno de Atotonilco in San Miguel de Allende.

- Historic center of Guanajuato City and its nearby mines.

State of Jalisco

- Historic center of Lagos de Moreno and its bridge.

- Historic center of Ojuelos de Jalisco.

- Bridge of Ojuelos de Jalisco.

- Hacienda de Ciénega de Mata.

- Old Cemetery of Encarnación de Díaz.

State of Aguascalientes

- Hacienda de Peñuelas.

- Hacienda de Cieneguilla.

- Historic center of Aguascalientes City.

- Hacienda de Pabellón de Hidalgo.

-

Templo de San Blas in Pabellón de Hidalgo.

State of Zacatecas

- Chapel of San Nicolás Tolentino of the Hacienda de San Nicolás de Quijas.

- Town of Pinos.

- Templo de Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles of Noria de Ángeles.

- Templo de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in Villa González Ortega.

- Colegio de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Propaganda Fide.

- Historic center of Sombrerete.

- Templo de San Pantaleón Mártir in Noria de San Pantaleón.

- Sierra de Órganos.

- Architectural set of Chalchihuites.

- Part of the Camino Real between Ojocaliente and Zacatecas.

- Cave of Ávalos.

- Historic center of Zacatecas City.

- Sanctuary of Plateros.

-

El Laberinto of Altavista archaeological zone in Chalchihuites.

State of San Luis Potosí

- Historic center of San Luis Potosí.

State of Durango

- Chapel of San Antonio of the Hacienda de Juana Guerra.

- Churches in the town of Nombre de Dios.

- Hacienda de San Diego de Navacoyán and Bridge del Diablo.

- Historic center of Durango City.

- Churches in the town of Cuencamé and Cristo de Mapimí.

- Templo de Nuestra Señora del Refugio in the Hacienda La Pedriceña in Los Cuatillos, Cuencamé Municipality.

- Iglesia Principal of San José de Avino.

- Chapel of the Hacienda de la Inmaculada Concepción of Palmitos de Arriba.

- Chapel of the Hacienda de la Limpia Concepción of Palmitos de Abajo.

- Architectural set of Nazas.

- Town of San Pedro del Gallo.

- Architectural set of Mapimí.

- Town of Indé.

- Chapel of San Mateo of the Hacienda de San Mateo de la Zarca.

- Hacienda de la Limpia Concepción of Canutillo.

- Templo de San Miguel in Villa Ocampo.

- Part of the Camino Real between Nazas and San Pedro del Gallo.

- Ojuela Mine.

- Cave of Las Mulas de Molino.

-

Plaza de Armas in the Historic centre of Durango City.

State of Chihuahua

- Town of Valle de Allende.

Map of the Sites

The Trail in the United States

In the United States, the original route of the Camino Real goes from the Texas–New Mexico border to San Juan Pueblo. This route is now a National Scenic Byway called El Camino Real. Parts of it follow modern highways like I-10 and I-25.

Over the last few decades, trails for walking, biking, and horseback riding have been added. These include the Paseo del Bosque Trail in Albuquerque. The Camino Real also connects to the Old Spanish Trail and the Santa Fe Trail in Santa Fe.

Along the trail, you can still find old stopovers called parajes. These include El Rancho de las Golondrinas. Historic forts like Fort Craig and Fort Selden are also located along the trail.

CARTA: Helping Preserve the Trail

The El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro Trail Association (CARTA) is a group that works to protect and teach people about this historic trail. They work with the U.S. National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and Mexican groups. CARTA publishes a magazine called Chronicles of the Trail. It shares history and news about what CARTA is doing to preserve the trail.

The Chihuahua Trail

The Chihuahua Trail is another name for the part of the Camino Real that goes through Chihuahua state in Mexico. It connects New Mexico to central Mexico.

By the late 1500s, Spanish explorers had moved north from Mexico City. They followed this trail all the way to Santa Fe. Until Mexico became independent in 1821, this 1,500-mile (2,400 km) (2,400 km) trail was the only way to communicate with New Mexico. Ox carts, mule trains, missionaries, soldiers, and colonists all used it. When the Santa Fe Trail opened, traders from the United States used the Chihuahua Trail to go further south. They went to places like Durango and Zacatecas. In the 1800s, railroads took over. But in the mid-1900s, the old Mexico City–Santa Fe road became one of Mexico's major highways. The part from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to El Paso, Texas, is now US State Highway 85. It was first used by Franciscan missionaries in 1581 and might be the oldest highway in the United States.

Images for kids

-

The section of the road in the US, about 646 kilometres (401 mi) (400 miles), became a National Historic Trail in 2000.

-

Church of San Blas in Pabellón de Hidalgo.

See also

In Spanish: Camino Real de Tierra Adentro para niños

In Spanish: Camino Real de Tierra Adentro para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |