Old Spanish Trail (trade route) facts for kids

|

The Old Spanish Trail

|

|

The route of the Old Spanish Trail.

|

|

| Location | New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, California |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 88001181 (original) 01000863 (increase 1) 08000229 (increase 2) |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | Utah: October 6, 1988 |

| Boundary increases | Nevada: August 22, 2001 Nevada: March 21, 2008 |

The Old Spanish Trail was an important trade route in the American Southwest. It linked settlements near Santa Fe, New Mexico with those in Los Angeles, California. This trail was about 700 miles long. It crossed tough lands like high mountains, dry deserts, and deep canyons. Many people consider it one of the hardest trade routes ever used in the United States.

Spanish explorers first found parts of the trail in the late 1500s. But it was mostly used by traders with pack trains from about 1830 to the mid-1850s. During this time, the area was part of Mexico. It became part of the United States in 1848.

The trail got its name from a report by John C. Frémont in 1844. He was guided by Kit Carson. Frémont's report showed that parts of the trail had been known by the Spanish since the 16th century. This trail was very important for New Mexico. It created a difficult but useful way to trade with California.

In 2002, the U.S. Congress made this trail part of the National Trails System. It is now called the Old Spanish National Historic Trail.

Contents

A Look Back: History of the Trail

The Old Spanish Trail was a mix of paths. These paths were first made by Native American people. Later, Spanish explorers, trappers, and traders used them. They traded with tribes like the Ute.

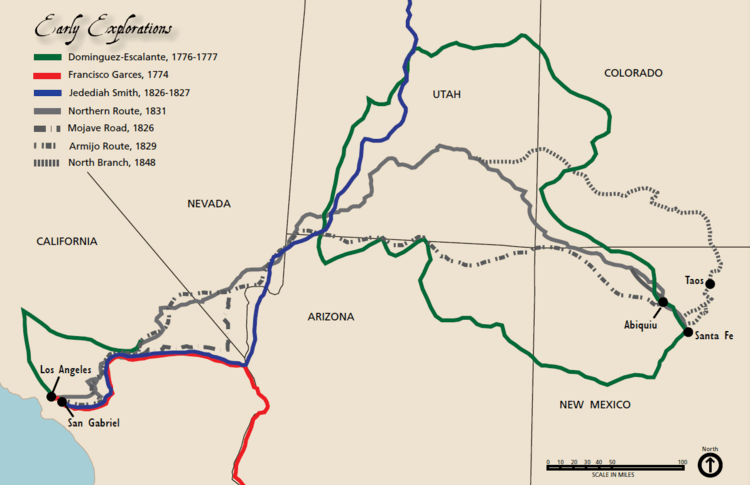

Early Explorations and Discoveries

In 1765, Juan Maria de Rivera explored the eastern parts of the trail. This included areas in what is now southwest Colorado and southeast Utah. In 1776, two Franciscan missionaries, Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, tried to reach California from Santa Fe. They got as far as the Great Basin near Utah Lake before turning back.

Other explorers, like Francisco Garcés and Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, also explored the southern region. They found shorter ways through the mountains and deserts. These routes connected Sonora to New Mexico and California. However, most of these did not become part of the Old Spanish Trail. One exception was some paths through the Mojave Desert.

The Mohave Trail was one such path. Francisco Garcés first traveled it from the Mohave villages on the Colorado River. He went west across the Mojave Desert, using desert springs. He then turned northwest to the Old Tejon Pass. He was looking for a route to Monterey. Garcés later returned to the Colorado River using the entire Mohave Trail. This trail was also used by the first Americans to reach California by land. This happened in November 1826 with an expedition led by Jedediah Smith. Today, the Mojave Desert part of the Mohave Trail is a jeep trail called the Mojave Road.

Opening the Trade Route

A full route linking New Mexico to California was opened in 1829-1830. This happened when Antonio Armijo, a merchant from Santa Fe, led a trade group. His group had 60 men and many mules. Armijo's group created a trade route. They used a network of Native American paths. They also used parts of Jedediah Smith’s routes from 1826 and 1827. They also used Rafael Rivera’s route from 1828 to the San Gabriel Mission through the Mojave Desert. Armijo wrote a report about his journey for the governor. The Mexican government published it in June 1830.

After this, traders usually made one round trip each year. News of Armijo's successful trip spread. Trade began between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. However, in 1830, fighting with the Navajo tribe made Armijo's route to the Colorado River difficult. A new route north of the river was needed. This new route used paths made by fur traders and trappers through Ute lands. It went northwest to the Colorado and Green rivers. Then it crossed to the Sevier River. It followed the Sevier River, then went west over mountains near Parowan, Utah. From there, it went south to the Santa Clara River. This connected it to Armijo's route to California.

Trading Goods and People

Trade usually involved one mule pack train from Santa Fe. It had 20 to 200 people and about twice as many mules. They brought goods like blankets, hand-woven by Native Americans in New Mexico, to California. California had many horses and mules, often wild, with no local market. These were easily traded for the woven goods. Usually, two blankets were traded for one horse. Mules were tougher, so they cost more blankets. California had few people who could process wool or weave. So, woven products were very welcome.

Trading groups usually left New Mexico in early November. This was to use the winter rains to cross the deserts. They would arrive in California in early February. The return trip usually left California in early April. This was to cross the trail before water holes dried up or melting snow made rivers too high. The returning groups often drove hundreds or even thousands of horses and mules.

New Settlements and Challenges

Some people from New Mexico started moving to California in the late 1830s. This happened as the fur trade began to slow down. New Mexicans settled in Alta California using this route. Some first settled in Politana. Then they started the towns of Agua Mansa and La Placita on the Santa Ana River. These were the first towns in what became San Bernardino and Riverside counties.

The trail was also used for some bad purposes. Some raiders attacked California ranches to steal horses and capture people. These captives were then sold in the large Native American slave trade. Mexicans, former trappers, and Native American tribes, especially the Utes, all took part in stealing horses. A leader named Walkara was known to steal hundreds or thousands of horses in one raid. Native Americans along the route, especially Paiute women and children, were at risk of being captured. They were sold as servants to Mexican ranchers and settlers in California and New Mexico. This slave trade caused long-lasting problems for people living along the trail. Sometimes, fighting between Native American groups happened because of these raids.

The Trail's End

John C. Frémont, known as "The Great Pathfinder," traveled the route in 1844. He was guided by Kit Carson. Frémont named the trail in his reports around 1848. Trade between New Mexico and California continued until the mid-1850s. By then, freight wagons and new wagon trails made the old pack trail less useful.

By 1846, both New Mexico and California became U.S. territories. This happened after the United States won the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). After 1848, many Mormon immigrants began settling along the trail in Utah, Nevada, and California. This changed trade and attitudes towards Native American slavery.

Today, the names of places in this article refer to current states and towns. Few settlements existed along the trail before 1850, except near the California coast. However, many natural features along the trail still have their Spanish names.

Exploring the Trail Routes

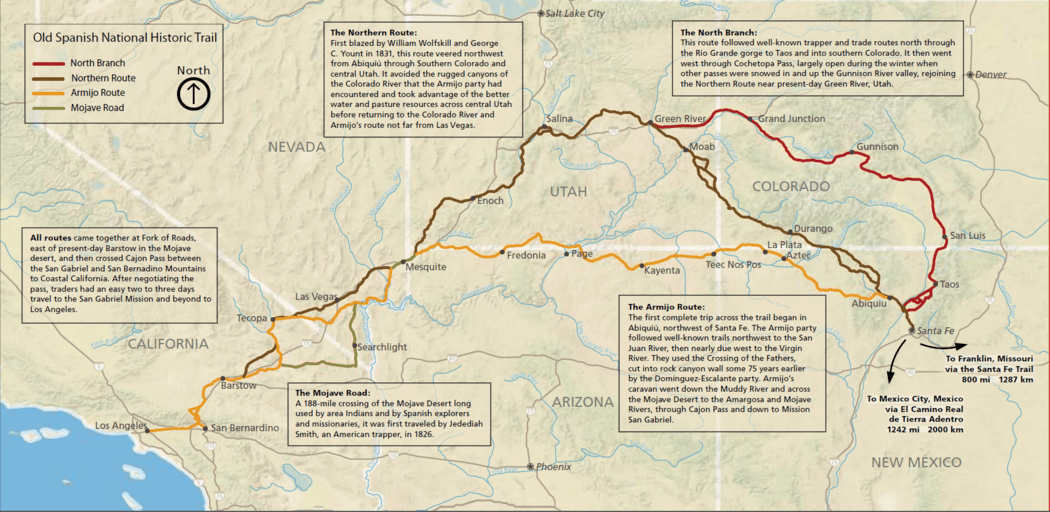

The Old Spanish Trail was not just one single path. It had several main routes and branches that travelers used.

Armijo's Original Route

The Armijo Route was the first main path. It was created by Antonio Armijo's group in 1829–1830. They left Abiquiu on November 7, 1829. They traveled northwest and west from Santa Fe. They followed the Chama River and the Puerco River. Then they crossed to the San Juan River basin.

From the San Juan, they entered the Four Corners area. They passed north of the Carrizo Mountains to Church Rock. This is east of today's Kayenta. The trail went to Marsh Pass and north through Tsegi Canyon. At the Colorado River, they crossed at the Crossing of the Fathers. This is above today's Glen Canyon Dam.

They kept going west to Pipe Spring. Then they went to the Virgin River near today's St. George, Utah. They followed the Virgin River to the Santa Clara River. They followed the Santa Clara River near the Shivwits Reservation. They crossed south over the Beaver Dam Mountains at Utah Hill Summit. They reached the Virgin River again. They followed it for three days to the Colorado River.

They traveled west next to the river, over tough land in the Black Mountains. This was to avoid the deep Boulder Canyon. They reached the green areas of Callville Wash and Las Vegas Wash by the river. Armijo waited there for his scouts. One scout, Rivera, had visited the Mohave villages downriver before. Rivera returned, recognizing the Mohave Trail that led west to Southern California. Armijo tried a shortcut southwest to the mouth of the Mojave River. This might have been to save time or because the Mohave people had been unfriendly to other groups.

From Las Vegas Wash on the Colorado River, Armijo's group went southwest. They passed Eldorado Dry Lake and the spring at Goodsprings Valley. They went through Wilson Pass, across Mesquite Valley and California Valley. They went through Emigrant Pass to Resting Springs. Then they followed the Amargosa River from near Tecopa to Salt Spring.

From Salt Spring, they crossed a two-day dry stretch up Salt Creek. They reached Laguna del Milagro ("Lake of the Miracle"), probably Silver Lake. Then they went to Ojito del Malpais ("little spring of the badlands") on Soda Lake. They had another dry day past Soda Lake. Then they reached the Mojave River. This river sometimes had drinkable water. The Mohave Trail led up this river.

By this point, Armijo's group was low on food. Armijo sent some scouts ahead to get food from the settlement at San Bernardino de Sena Estancia. They followed the river for six days, killing a mule or horse each day for food. Near Summit Valley, they met vaqueros (cowboys) from San Bernardino de Sena Estancia who had extra food. Armijo did not cross the mountains using the Mohave Trail over Monument Peak. Instead, he followed a route he called "Cañon de San Bernardino." This went from the upper Mojave River west through Cajon Pass and down Crowder and Cajon canyons. This led to the coastal plain of San Bernardino Valley. This route was likely known to the vaqueros.

Once through the pass, they turned west. They followed the base of the San Gabriel Mountains for two days to San Jose Creek. They followed it, crossed the San Gabriel River at the Rancho La Puente. They reached Mission San Gabriel Arcángel on January 30, 1830. Armijo used the same route to return home, traveling from March 1 to April 25, 1830. He wrote a short diary of his trip. It listed the places where they camped but not distances. The Mexican government published it in June 1830.

The Main Northern Route

The Main Northern Route avoided Navajo land. It also avoided the harder canyon country of the Armijo Route near the Colorado River. William Wolfskill and George Yount first traveled this route in 1830. This path went northwest from Santa Fe through southwestern Colorado. It passed the San Juan Mountains, Mancos, and Dove Creek. It entered Utah near today's Monticello.

The trail continued north through tough land to Spanish Valley near today's Moab, Utah. There, a ferry crossed the wide Colorado River. Then it turned northwest to a ferry crossing on the large Green River near today's Green River, Utah. The route then went through or around the San Rafael Swell. This was the northernmost point of the trail.

Entering the Great Basin in Utah through Salina Creek Canyon, the trail turned southwest. It followed the Sevier, Santa Clara, and Virgin Rivers to the north bank of the Colorado River. From there, travelers could follow the Colorado River to Las Vegas Wash. Then they went south through the Eldorado Valley and Piute Valley to join the Mojave Trail. This was west of the Mohave villages. They followed the route between the springs along the Mojave Trail to Soda Lake and the Mojave River. Later groups could also use the Armijo Route. This route turned southwest from the Colorado at Las Vegas Wash. It went to Resting Springs and to the Mojave River. From there, it joined the Wolfskill/Yount Route. They followed that river up and over the San Bernardino Mountains through Cajon Pass. Then they went through Crowder Canyon and lower Cajon Canyon. Finally, they crossed the coastal valleys to Mission San Gabriel and Los Angeles.

The Northern Branch

The North Branch of the Old Spanish Trail was used by traders and trappers. It used Native American and Spanish colonial paths. It went from Santa Fe north to Taos and into the San Luis Valley of Colorado. Groups then headed west to today's Saguache. They crossed the Continental Divide at Cochetopa Pass. Then they went through present-day Gunnison and Montrose to the Uncompahgre Valley.

The trail then followed the Gunnison River to today's Grand Junction. There, the Colorado River was crossed. Then it went west to join the Main Northern Route just east of the Green River. The North Branch later became important for explorers looking for railroad routes. In 1853, three groups explored the North Branch over Cochetopa Pass. These groups were led by Lieutenant Edward Fitzgerald Beale, Captain John Williams Gunnison, and John C. Frémont.

Trail Changes Over Time

Between 1829 and 1848, the Old Spanish Trail changed a lot. Travelers found or made easier paths. But no matter the route, the trail crossed mountains and dry areas. It had limited grass and sometimes little water. It crossed two deserts. Often, the bones of horses that died of thirst were seen along the way.

The western parts of the trail could only be used reliably in winter. This was when rains or snow brought water to the desert. In summer, there was often no water, and the extreme heat could be deadly. Only one round trip per year was usually possible. After 1848, the western parts of the trail were used in winter. This allowed travel between Utah and California when other trails were closed by snow.

Frémont's Shortcut

One important change to the route was made by John C. Frémont in 1844. His group left the Armijo Route at Resting Spring. They turned northeast after crossing the Nopah Range through Emigrant Pass. They went through California Valley and across Pahrump Valley to Stump Spring. Then they went into the mountains to Mountain Springs and Cottonwood Spring. Finally, they reached Las Vegas Springs.

He then crossed 50 dry miles to the Muddy River. He rejoined the Main Route on the Virgin River at Halfway Wash. This was after crossing what became known as Mormon Mesa. This route saved a lot of distance. It avoided the long detours of the Armijo and Main routes that followed the Colorado River. This shortcut later became the Mormon Road, a wagon road between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles.

Preserving and Remembering the Trail

In 1988, a part of the trail in Arches National Park was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2001, the section of the trail in Nevada was also added. It runs from the Arizona border to California. It is called the Old Spanish Trail/Mormon Road Historic District.

The Old Spanish Trail became the fifteenth national historic trail in 2002. This happened when Congress passed a bill and President George W. Bush signed it.

Today, not many parts of the original trail remain. But the trail is remembered in many local street and road names. There are also many historical markers in the states it crossed. Parts of US 160 in Colorado and US 191 in Utah are also named after the trail.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Viejo Sendero Español para niños

In Spanish: Viejo Sendero Español para niños