San Gabriel River (California) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids San Gabriel River |

|

|---|---|

The channelized San Gabriel River in Los Alamitos, near its confluence with Coyote Creek

|

|

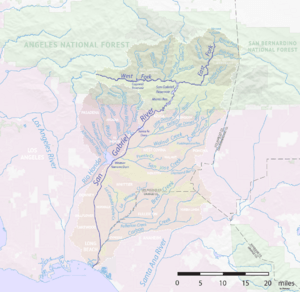

Map of the San Gabriel (yellow) and Rio Hondo (purple) watersheds.

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Counties | Los Angeles County, Orange County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | East Fork San Gabriel River Angeles National Forest, San Gabriel Mountains 4,493 ft (1,369 m) 34°20′35″N 117°43′30″W / 34.34306°N 117.72500°W |

| River mouth | Pacific Ocean Alamitos Bay, Long Beach/Seal Beach 0 ft (0 m) 33°44′33″N 118°06′56″W / 33.74250°N 118.11556°W |

| Length | 58 mi (93 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 689 sq mi (1,780 km2) |

| Tributaries |

|

The San Gabriel River is a waterway in California, flowing about 58 miles (93 km) south through Los Angeles and Orange Counties. It's one of the three main rivers in the Greater Los Angeles Area. The river's watershed starts in the rugged San Gabriel Mountains. It then flows through the developed San Gabriel Valley and the Los Angeles coastal plain. Finally, it empties into the Pacific Ocean between Long Beach and Seal Beach.

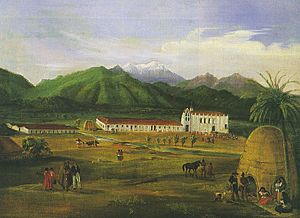

Long ago, the San Gabriel River flowed across a wide, flat area. Its channels often changed during winter floods. This created many wetlands, which were a rare source of fresh water in this dry region. The Tongva people lived in the San Gabriel River basin for thousands of years. They relied on the river's fish and game. The river is named after the nearby Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. This mission was built in 1771 during the Spanish colonization of California.

Spanish, Mexican, and American settlers used the river's water for farming and ranching. This was before cities started growing in the early 1900s. Eventually, much of the area became industrial and suburban. Big floods in 1914, 1934, and 1938 led to building dams and debris basins. Much of the lower river was also made into a straight channel with concrete banks. Today, the river provides about one-third of the water used in southeast Los Angeles County.

The upper San Gabriel River has been mined for gold since the 1860s. Its deep gravel bed has also been important for construction aggregate since the early 1900s. The river is a popular place for fun activities. There are parks and trails along its flood basins. The headwaters of the San Gabriel River are still natural. They are a popular spot in the Angeles National Forest.

Contents

Exploring the San Gabriel River's Journey

The San Gabriel River basin covers 689 square miles (1,780 km2). It is located between the Los Angeles River to the west and the Santa Ana River to the east. To the north is the Mojave Desert. The river's journey has three main parts.

The Mountainous North

The northern part is in the Angeles National Forest of the San Gabriel Mountains. This area is steep and rocky. It gets the most rain and snow, about 33 inches (840 mm) per year. This is where almost all the river's natural water comes from. The highest point is Mount San Antonio (Mount Baldy), at 10,064 feet (3,068 m). In winter, many areas above 6,000 feet (1,800 m) are covered in snow.

The San Gabriel Valley and Coastal Plain

The middle part is the San Gabriel Valley. The southern part is the coastal plain of the Los Angeles Basin. These two areas are separated by the Puente Hills and Montebello Hills. Most of these valleys are now covered by cities. About 2 million people live in the river's watershed.

The climate here is very dry. There is only moderate rain in winter and almost none in summer. The lower part of the river used to flood seasonally. This created large swamps and wetlands. Today, very little of this natural environment remains.

River Flow Changes

The San Gabriel is one of Southern California's largest natural streams. But its water flow changes a lot each year. Historically, the river had its highest flows in winter and spring. Flows dropped a lot after early June. Today, dams and water diversions have dried up some parts of the river. Other parts have more water due to treated wastewater runoff.

East Fork Headwaters

The East Fork is 17 miles (27 km) long. It is the biggest source of the San Gabriel River. It starts high up at Pine Mountain, 9,648 feet (2,941 m), in the Sheep Mountain Wilderness. It flows through a remote valley with large meadows. Then it turns south and flows through a steep canyon.

The East Fork flows through a deep gorge called the "Narrows." Here, Iron Mountain rises 8,007 feet (2,441 m) to the southeast. Mount Hawkins, 8,850 feet (2,700 m), rises to the northwest. Near the end of the Narrows, the river goes under the Bridge to Nowhere. This 120-foot (37 m) high bridge was left behind after a huge flood in 1938. The flood washed out a highway being built along the East Fork. Today, the bridge is a popular spot for hikers and bungee jumpers.

After the Narrows, the river flows south through a more open valley. It then turns sharply west. It flows into San Gabriel Reservoir, where it meets the West Fork.

West Fork Headwaters

The West Fork is 19 miles (31 km) long. It starts at Red Box Saddle, a visitor center along the Angeles Crest Highway. It begins at 4,666 feet (1,422 m) elevation. The West Fork flows at a lower elevation than the East Fork. It also carries less water. It flows east in a fairly straight line. From its start, the river quickly goes down to the Cogswell Reservoir.

Below Cogswell Dam, a road (Forest Route 2N25) runs next to the river. This road is only for walking or biking. The river flows east through a winding canyon. It forms the southern edge of the San Gabriel Wilderness. It then flows into San Gabriel Reservoir, joining the East Fork.

North Fork Headwaters

The North Fork is the shortest and steepest of the three main forks. It starts as streams falling from the mountains between Mount Islip and Mount Hawkins, over 7,000 feet (2,100 m) high. It flows south for 4.5 miles (7.2 km). It forms a braided channel along its wide canyon floor. It flows into the West Fork near San Gabriel Reservoir.

The North Fork is the most developed fork. It has many campgrounds and facilities. The popular Crystal Lake Recreation Area is in the upper North Fork. It has the only natural lake in the San Gabriel Mountains. Highway 39 follows the North Fork valley. The upper part of this road has been closed since 1978 due to landslides.

San Gabriel Canyon and Dams

Below where the East Fork and West Fork meet, the San Gabriel River flows through the deep San Gabriel Canyon. This is the only major break in the southern San Gabriel Mountains. This part of the river now has large reservoirs for water supply and flood control. San Gabriel Dam, a 325-foot (99 m) high rockfill dam, creates the 44,183-acre-foot (54,499,000 m3) San Gabriel Reservoir. The concrete gravity Morris Dam, just downstream, creates the 27,800-acre-foot (34,300,000 m3) Morris Reservoir. A small power plant in Azusa gets water from the San Gabriel River below San Gabriel Dam.

The water levels in the upper San Gabriel Reservoir change a lot. It is mainly used for flood control and to manage sediment. During the dry season, the reservoir is often low. This leaves room for stormwater and allows workers to remove built-up dirt. The northern part of the reservoir, when dry, is also used for OHV riding. You cannot boat on San Gabriel Reservoir or Morris Reservoir. Morris Reservoir was used by the U.S. Navy for torpedo testing until the 1990s.

Journey Through San Gabriel Valley

The river leaves San Gabriel Canyon at Azusa, below Morris Dam. Here, it enters the wide, flat alluvial plain of the San Gabriel Valley. Most of the river's flow is diverted into spreading grounds. These help refill the local San Gabriel Valley aquifer, which is an important water source. The riverbed then continues southwest, usually dry. It passes under Interstate 210 into the flood control basin behind Santa Fe Dam.

Past the Santa Fe Dam, the river flows through Irwindale. This area has many large gravel quarries. They have been digging up the river's rich sediments since the early 1900s. From here, Interstate 605 (the San Gabriel River Freeway) runs next to the river. In the San Gabriel Valley, the river flows in an earth-bottomed channel. It has artificial concrete or riprap banks. Below Interstate 10 at El Monte, Walnut Creek joins the river. This brings a small amount of water back to the river year-round.

The river then enters the Whittier Narrows. This is a natural gap between the Puente and Montebello Hills. Here, it is held back by the Whittier Narrows Dam. This dam is also mainly for flood control. The Rio Hondo also flows through the Whittier Narrows. Historically, these two rivers sometimes joined each other. Today, the Whittier Narrows Dam controls their flow into fixed channels.

The Lower River's Path to the Ocean

Below the Whittier Narrows Dam, the river flows south-southwest. It roughly marks the border between Los Angeles County and Orange County. It flows through Whittier and Pico Rivera. It passes under Interstate 5 to Downey, where it becomes a concrete channel. The San Gabriel River Bike Trail runs next to the river for 28 miles (45 km) to the Pacific Ocean.

From Cerritos, the river flows south-southeast. It meets Coyote Creek, its largest lower tributary. A short distance below Coyote Creek, the riverbed changes back from concrete to earth. It passes under Interstate 405 and the Pacific Coast Highway. It then empties into the Pacific Ocean between Alamitos Bay and Anaheim Bay. This is on the border of Long Beach and Seal Beach.

How the San Gabriel River Formed

The San Gabriel River, its canyons, and its flat areas are geologically young. They exist because of forces along the San Andreas Fault. This fault is where the North American Plate and Pacific Plate meet. The San Gabriel Mountains are a fault block mountain range. They are a huge piece of rock lifted up by the San Andreas Fault. The mountains are still rising about 2 inches (51 mm) per year. The Puente and Montebello hills are even younger, less than 1.8 million years old. As these hills formed, the San Gabriel River kept its path, cutting through the Whittier Narrows.

The San Gabriel Mountains are made of old, broken, and unstable rock. This means they erode a lot. Heavy winter storms cause fast erosion, creating the dramatic canyons of the San Gabriel River. In the winter, the mountains have many landslides and mudslides. This has led to building many debris basins to protect towns.

During floods, the river carries huge amounts of sediment from the mountains. This includes sand, gravel, clay, and even car-sized boulders. About 5 million years ago, the Los Angeles Basin sank down. At the same time, the San Gabriel River deposited a huge alluvial fan. This created the flat valley floor. In the San Gabriel Valley, river deposits can be up to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) deep.

Before cities were built, the river channels were not well-defined. They often changed course with each winter storm. Sometimes the river joined the Rio Hondo and flowed into the Los Angeles River. Other times, it flowed south to Alamitos Bay or Anaheim Bay. Every few decades, a big storm would cause the rivers to flood at the same time. This would cover the coastal plain with water.

The thick sediments in the lowlands also hold a large local aquifer system. This is an underground layer of water. Historically, this water was close to the surface. Natural artesian wells existed in many places. In the 19th century, large-scale farming began. This caused the water level to drop as farmers drilled many wells. Today, the San Gabriel Valley aquifer is an important source of water. Water is added back to it using local runoff and water from other areas.

Wildlife and Nature Along the River

The San Gabriel River once had a rich ecosystem on its wide floodplain. This area was flooded many times each year by rain and snowmelt. This created a 47,000-acre (19,000 ha) network of riparian (riverbank) and wetland habitats. These included seasonal flood areas, alkali meadows, and forests of willows, oaks, and cottonwoods. There were also fresh and saltwater marshes. At its mouth, the river flowed into a large estuary with thousands of acres of marsh and swamp. In the mountains, the river channel is often too narrow for much plant life. Winter floods tend to wash the channel down to bare rock.

Today, most streams are in artificial channels. Most of the original wetlands have been lost to city growth. Less than 2,500 acres (1,000 ha) of wetlands remain in the San Gabriel River watershed. Most remaining wetlands are next to the river or in flood control basins. They provide homes for birds and small mammals. Also, projects are working to restore riverbank and wetland areas. For example, an artificial wetland and bioswale system is planned near El Monte. It will be a recreation area, wildlife habitat, and help with pollution.

Forests and Wildfires

Above 7,000 feet (2,100 m), the San Gabriel Mountains have some pine and fir forests. These are what's left of a huge evergreen forest that once covered Southern California. This was during the last ice age when the climate was much wetter. These mountain forests are home to large animals like deer and black bears. The upper San Gabriel watershed was never heavily logged. The 17,000-acre (6,900 ha) San Dimas Experimental Forest is also in the watershed. It is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve where forest water has been studied since 1933. Lower down, chaparral and brush plants are common. The Puente Hills have special plant communities like coastal sage scrub and walnut forests.

Wildfires are a natural part of these plant communities. However, after the 1938 flood, a strong program to stop wildfires began. This was because burned areas erode quickly during storms, causing mudslides. This has caused a lot of dry plant material to build up. This increases the risk of bigger fires. Droughts in the early 2000s led to huge fires. The 2002 Curve Fire burned 20,000 acres (8,100 ha), much of it in the North Fork. The 2009 Station Fire was the largest in Los Angeles County's history. It burned much of the upper West Fork. As cities grow closer to the mountains, the risk of property damage from fires also grows.

Fish and Aquatic Life

The San Gabriel River used to have many native fish. This included the largest runs of steelhead trout in Southern California. Steelhead once swam over 60 miles (97 km) upriver from the Pacific Ocean to lay their eggs. It was known as one of the "best steelhead fishing rivers in the state." But irrigation, dams, and river channeling have almost wiped out steelhead in the San Gabriel basin. Since the 19th century, rainbow trout (steelhead that live only in fresh water) have been put into the upper forks. This is for people to fish. About 60,000 rainbow trout are stocked each year. The West Fork also has the largest remaining population of arroyo chub. This fish lives only in Southern California streams.

Human History Along the San Gabriel River

Humans have lived in the San Gabriel River area for at least 2,500 years. Before Spanish explorers arrived, there were an estimated 5,000–10,000 native people. Most of the San Gabriel River was in the traditional land of the Tongva (Gabrielino) people. The Chumash also used the area. Tongva villages were usually on high ground, safe from floods. A typical village had large, round huts called "kich" or "kish." Each hut was home to several families.

In summer, villagers would go up the San Gabriel Canyon into the mountains to gather food. The San Gabriel River also provided food like steelhead trout and game animals. The many plants around the river and its marshes, like tule, were used to build homes and canoes. The Tongva often set small fires to clear old plants. This helped new plants grow for game animals. They also made oceangoing canoes using wooden planks and tar from local oil seeps.

At least 26 Tongva villages were along the San Gabriel River. One of the largest, Asuksangna, was at the mouth of the San Gabriel Canyon. The West Fork canyon was part of a trade route. This allowed the Tongva to trade with the Serrano people in the Mojave Desert. The San Gabriel Valley had the most people because of its fertile soil and more rain.

Early Explorers and Missions

The San Gabriel River basin had a lot of water, which was rare in dry Southern California. This made it an attractive place for early European settlers. Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed past the river's mouth in 1542. He met the native Tongva, who came out in canoes. The first Spanish group to cross the river was the Portolà expedition in 1769. Juan Crespí, a missionary, described the river as flowing "among many green marshes, their banks covered with willows and grapes."

The expedition had to build a bridge across the river because it was too swampy. This area became known as "la puente" (the bridge). The modern city of La Puente gets its name from this.

After the Portolà expedition, Spain claimed California. The San Gabriel River was called "Río San Miguel Arcángel." Mission San Gabriel Arcángel was founded in 1771 by Junípero Serra. It was built along the San Gabriel River near present-day Montebello. The mission's name was soon given to the river and the San Gabriel Mountains. The original mission site flooded often, so it moved to its current location in San Gabriel in 1775. The mission eventually controlled 1,500,000 acres (610,000 ha) of land.

The Spanish tried to gather Native Americans into central communities. They offered gifts, but often used force. Native people worked on mission farms and ranches. They were also converted to Christianity. Native Americans who ran away from the mission system hid in the upper canyons of the San Gabriel River. A resistance movement lasted for many years. This included the San Gabriel mission uprising in 1785, led by Tongva medicine woman Toypurina.

Diseases greatly reduced the native populations. By the early 1800s, most surviving Gabrieliño had entered the mission system. By 1830, the native population was about a quarter of what it was before Spanish colonization.

Ranchos and American Control

To attract settlers, Spain and later Mexico created large land grants. These became the many ranchos in the area. The decline of Native American populations made it easy for colonists to take large areas of land. During the Spanish and Mexican periods (until 1846), cattle ranching was the main economy. Many ranchos were located in the San Gabriel River watershed.

California became a U.S. state in 1850. One important battle of the Mexican–American War was fought on January 8, 1847, on the San Gabriel River. This was the last defense line for Mexican forces. American forces crossed the river under heavy fire. They forced the Mexicans from their position in under 90 minutes. After taking control of the river, the Americans took Los Angeles on January 10. The Mexicans surrendered California three days later. This event is known as the Battle of Rio San Gabriel.

The Gold Rush in San Gabriel

People had rumored about gold in San Gabriel Canyon for many years. Gold was first confirmed in the upper San Gabriel River around April 1855. The Los Angeles Star reported that prospectors found "gold of the best quality."

The river was quiet for a few years due to drought. But the winter of 1858-59 was wet. Soon, hundreds of gold seekers came to the river. By May 1859, claims were made along 40 miles (64 km) of the San Gabriel Canyon. It was hard to get to the diggings because the rocky riverbed was the only way in. In July 1859, stagecoach service started to bring miners and supplies.

Between 1855 and 1902, an estimated $5,000,000 worth of gold was taken from the San Gabriel River. Miners started with simple gold panning. Then they used more advanced methods like sluices and hydraulic mining. Dams and waterwheels helped them get gold from the river gravel. Some tunnel mining also happened in later years.

Large settlements grew in the rough country along the upper San Gabriel River. Prospect Bar grew to include stores and shops. A flood in November 1859 destroyed it. But four months later, it was rebuilt as Eldoradoville. This town was near the East Fork and Cattle Canyon. From 1859 to 1862 was the best time for the San Gabriel gold rush. Wells Fargo shipped about $15,000 worth of gold per month from Los Angeles County. Most of it was from the San Gabriel diggings.

By 1861, Eldoradoville had about 1,500 people. The town did well until the Great Flood of 1862. This was the largest flood in California's recorded history. It swept the canyon clean. "A wall of churning gray water swept down the canyon, obliterating everything in its path." Shacks, supplies, and mining equipment were all washed away.

Mining continued after the 1862 flood, but never as much. A second wave of gold seeking began in the early 1930s along the East Fork. A 1932 Los Angeles Times article called it a "leisurely gold rush." It reported that over 500 people lived along the stream. They lived in shacks, tents, and cars. For many, it was a way to earn money during the Great Depression. These mining camps were also destroyed by the great flood of 1938.

Today, recreational gold mining continues. However, it is not legal in many places. The U.S. Forest Service says that lands in the East Fork are "not open to prospecting or any other mining operations." But this rule is often not enforced.

Farming and Water Use

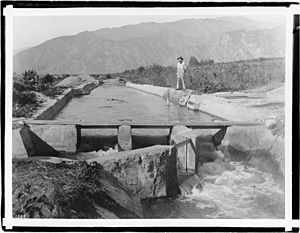

Southern California's climate is good for farming. But the seasonal rainfall made it hard to grow crops without irrigation. After Mission San Gabriel was founded, the Spanish built canals (zanjas) and reservoirs. These irrigated crops, powered mills, and watered livestock. The earliest record of water diversion for the mission is around 1773.

After California became part of the United States in 1846, ranching changed to farming. The San Gabriel River became a key water source. The California Gold Rush brought many people to the state. The high demand for food made the San Gabriel River Basin a very productive farming area. Railroads arrived in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This allowed the region to export farm products.

Some areas had easy access to water, like the "island meadow" between the Rio Hondo and San Gabriel Rivers. This was a popular spot for early American settlers. But most areas needed irrigation. The East and West Forks of the San Gabriel River carry water all year. Even in dry summers, the San Gabriel flowed to the mouth of San Gabriel Canyon. Here, it soaked into the San Gabriel Valley aquifer. Most water diversions were taken here or near the Whittier Narrows.

By 1907, the San Gabriel River irrigated some of the "most highly productive citrus regions of Southern California." The Teague Grove in San Dimas was once one of the largest citrus groves in the world.

Conflict over San Gabriel River water became intense in the 1880s. This led to the creation of the San Gabriel River Water Committee in 1889. This committee manages the distribution of San Gabriel River waters. This agreement is still in effect today.

Modern River Management

In the early 1900s, Los Angeles grew and needed more water. But all the river water was already used by farmers. In 1913, the Los Angeles Aqueduct opened. It brought water from the distant Owens Valley. This allowed cities to grow where farms once were. New industries moved to the San Gabriel River area. Oil was discovered in the Whittier Narrows in 1912. By 1920, almost 100 wells were pumping oil along the river. The Montebello Oil Field still produces oil today.

The Pacific Electric railway system, created in 1911, helped new communities grow. It connected them to downtown Los Angeles. A major bridge, the Puente Largo, was built in 1907. It carried the railway over the San Gabriel River. It was the largest bridge built in Southern California at that time.

The San Gabriel River flooded greatly in 1914. This caused much damage. That year, the Los Angeles County Flood Control Act was passed. The county began a program to build dams. A drought in the 1920s also showed the need for dams to store water. In 1924, engineer James Reagan proposed a big dam project. He hoped it would manage floods and save water.

Construction of the "Forks Dam" began in December 1928. It was meant to be the tallest dam in the world. But on September 16, 1929, a huge landslide buried the dam site. No lives were lost, but it was found that a dam could not be built safely there.

Despite this, the effort to dam the San Gabriel River continued. In April 1934, the county completed the Cogswell Dam. A month later, Pasadena completed Morris Dam. This dam supplied water to its residents. Morris Dam was later sold to the flood control district.

The largest dam, San Gabriel Dam, was almost finished before the Los Angeles flood of 1938. This was the most damaging flood in Southern California's history. Storms in late February and early March 1938 dropped a year's worth of rain in one week. The new dams reduced a huge flood crest. This saved a large part of the San Gabriel Valley from damage.

After World War II, roads into the mountains became more important. The state tried to build a road over the San Gabriel Mountains. Construction began in 1929 on the East Fork Road. But the 1938 flood destroyed the road and most of its bridges. Only the Bridge to Nowhere remains. Later attempts to build roads were also stopped by mudslides and erosion.

Camps and Resorts

As Los Angeles grew, trips to the San Gabriel Mountains became popular. In 1891, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce asked Congress to protect mountain areas for recreation. In 1892, the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve was created. This was the start of the Angeles National Forest.

The canyons, quiet after the gold miners left, became busy with resorts. These were built along the San Gabriel River forks. Between 1890 and 1938, hiking was very popular. Camp Bonito was a major resort. It was known for its "splendid trout streams." Other resorts included Cold Brook Camp and Opids Camp.

At first, you could only reach the upper San Gabriel River by hiking or horseback. The Mount Lowe Railway opened in 1893. It brought vacationers near the summit of Mount Wilson. As cars became popular, roads went deeper into the mountains. By 1915, a paved road reached the forks of the San Gabriel. This made it easier to get to the many camps.

Hiking popularity dropped during World War II. But it increased again after the war. Today, the upper San Gabriel is still heavily used for hiking, camping, fishing, swimming, and backpacking.

River Changes and Modern Uses

Controlling Floods

Before the 1900s, the San Gabriel River area was mostly for farming. When the river flooded, there was limited loss of life and property. The river's changing path below the Whittier Narrows made it hard to build permanent towns. A flood in 1868 caused the river to change course. It moved towards its present mouth at Alamitos Bay. The old western channel is now the Rio Hondo. The new channel is roughly its current path.

After the 1938 flood, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built two large flood control basins. These were Santa Fe Dam and Whittier Narrows Dam. They were finished in 1949 and 1957. These dams do not store water permanently. Their combined capacity of 112,000 acre-feet (138,000,000 m3) is only for flood control. Santa Fe Dam also stops destructive mudslides from the San Gabriel Canyon. Whittier Narrows Dam can move extra floodwaters between the San Gabriel River and Rio Hondo.

Another result of the 1938 flood was the channeling of Southern California streams. This included the San Gabriel River. Almost the entire lower river has been turned into an artificial channel. However, only about 10 miles (16 km) of the San Gabriel River channel (between Whittier Narrows Dam and Coyote Creek) is fully concrete. The channel is built to handle a 100-year flood.

Supplying Water

The San Gabriel River is an important water source for the 35 cities and communities in its watershed. Even though the climate is dry, the San Gabriel still provides about a third of the local water. The Cogswell, San Gabriel, and Morris dams can capture and store up to 85,000 acre-feet (105,000,000 m3) of rain and snow runoff. The Upper San Gabriel Valley Municipal Water District estimates that 95–99 percent of stormwater runoff is captured each year. The California Department of Water Resources considers the San Gabriel River a "fully appropriated" stream. This means no new water rights can be taken.

Two major underground water basins (aquifers) are under the San Gabriel River watershed. They are separated by rock and fault lines. Groundwater is the main long-term water storage. The aquifers can hold much more water than surface reservoirs. The San Gabriel Valley Basin covers 255 square miles (660 km2). It can store 10.8 million acre feet of groundwater. The Central Basin is larger, covering 277 square miles (720 km2). It can store 13.8 million acre feet.

The Los Angeles County Department of Public Works (LADPW) operates many spreading grounds. These areas receive water from the San Gabriel River. They allow it to soak back into the aquifers. The San Gabriel/Rio Hondo system has seven spreading grounds. These help recharge the San Gabriel Valley aquifer and the Central Basin aquifer. Rubber dams can also be inflated along parts of the river. This slows the water flow and allows it to soak directly into the riverbed.

Water distribution in the San Gabriel Valley is managed by the Main San Gabriel Basin Watermaster. This board decides how much water goes to each user. It also decides how much water is put into and pumped from the aquifer.

Generating Hydroelectricity

There is one hydroelectric plant on the river, north of Azusa. The original Azusa Hydroelectric Plant was built in 1898. It generated 2,000 kilowatts (KW) of power. In the early 1900s, it powered the Pacific Electric (Red Car) and Los Angeles Railway (Yellow Car) systems. The plant was bought by the City of Pasadena in 1930. A new 3,000 KW plant was built in the 1940s.

The power station gets water from the 5.5-mile (8.9 km) long Azusa Conduit. This conduit draws water from the river below San Gabriel Dam. It runs along the east wall of the San Gabriel Canyon. It then drops 390 feet (120 m) down the mountainside to the powerhouse. Using river water for electricity can dry up the channel. This reduces fish habitat.

Mining Sand and Gravel

The San Gabriel River bed is full of sand and gravel. It is an important source of materials for construction. The San Gabriel Valley around Irwindale is one of the largest mining areas in the United States. Over a billion tons have been taken from the old riverbed. Most of the freeway system in greater Los Angeles was built using these materials.

In Irwindale, there are seventeen gravel pits. The largest company is Vulcan Materials Company. There are plans to fill some inactive pits. They could be used for businesses, shops, or parks. They could also become water storage reservoirs.

Sediment is also removed from the reservoirs along the San Gabriel River. The San Gabriel River drains one of the most eroding mountain ranges. Reservoirs must be constantly cleaned to keep space for flood control. Between 1935 and 2013, about 42,000,000 cubic yards (32,000,000 m3) of sediment was removed from Cogswell and San Gabriel Reservoirs. This material is often not good for construction. It must be put in special disposal sites.

Water Quality Concerns

More than half of the watershed is developed. This means the San Gabriel River receives a lot of industrial and urban runoff. This causes pollution in the lower river. Several large wastewater treatment plants also discharge water into the river. The largest is the Los Coyotes plant, which releases 30 million gallons per day. A total of 598 businesses are allowed to discharge storm water into the river. More than 100 storm drains empty directly into the river. The upper parts of the river are undeveloped. But they are used a lot for recreation. This leads to trash, debris, and other pollution. The U.S. Forest Service removes about four hundred 32-gallon bags of trash from the East Fork each weekend.

A 2007 study found that Coyote Creek had "acute and chronic toxicity" from pesticides and industrial chemicals. But pollution levels in the main San Gabriel River, Walnut Creek, and San Jose Creek were "significantly reduced" from 1995 levels. This was due to better water treatment. The Alamitos and Haynes power stations discharge cooling water into the river. This has harmed the habitat around the river's estuary. A lot of the groundwater in the San Gabriel River watershed is also polluted. This is mostly from industrial chemicals. The San Gabriel Valley has four Superfund sites. Here, water is extracted for treatment before being pumped back into the ground.

River Crossings

From mouth to source (year built in parentheses):

- Marina Drive (1963)

SR 1 - Pacific Coast Highway (1931)

SR 1 - Pacific Coast Highway (1931)- Westminster Avenue - twin bridges (1964)

SR 22 - East 7th St - twin bridges (1941, 1959)

SR 22 - East 7th St - twin bridges (1941, 1959)- College Park Drive (1964)

- Southbound Interstate 605 ramp to northbound Interstate 405 (1966)

I-405 - San Diego Freeway (1964)

I-405 - San Diego Freeway (1964)- Southbound Interstate 405 ramp to northbound Interstate 605 (1966)

- East Willow Street (1962)

- East Spring Street (1952)

- East Wardlow Road (1963)

- San Gabriel River Bicycle Path [bike bridge]

- Carson Street - twin bridges (1971)

- Del Amo Boulevard (1966)

- South Street (1952)

- 183rd Street (1972)

- Artesia Boulevard (1941)

- Railroad (West Santa Ana Branch, disused)

SR 91 - Artesia Freeway (1968)

SR 91 - Artesia Freeway (1968)- [Pedestrian Bridge]

- Alondra Boulevard (1952)

- Rosecrans Avenue (1951)

- Foster Road [Pedestrian Bridge]

- Eastbound Interstate 105 ramps to Interstate 605 (1987)

I-105 - Glenn Anderson Freeway and Metro Green Line (1987)

I-105 - Glenn Anderson Freeway and Metro Green Line (1987)- Interstate 605 ramps to westbound Interstate 105 (1987)

- Imperial Highway (1952)

- Railroad (Union Pacific)

- Firestone Boulevard (1934)

- Florence Avenue (1951)

I-5 - Santa Ana Freeway (1953)

I-5 - Santa Ana Freeway (1953)- Telegraph Road (1937)

- Railroad (Union Pacific)

- Slauson Avenue (1958)

- Railroad (BNSF)

- Washington Boulevard (1953)

SR 72 - Whittier Boulevard (1968)

SR 72 - Whittier Boulevard (1968)- Railroad

- East Beverly Boulevard (1952)

- San Gabriel River Parkway (1954)

- Whittier Narrows Dam

- Peck Road - twin bridges (1952)

SR 60 - Pomona Freeway (1967)

SR 60 - Pomona Freeway (1967)- Valley Boulevard (1916)

- Railroad

I-10 - San Bernardino Freeway (westbound 1933, eastbound 1956)

I-10 - San Bernardino Freeway (westbound 1933, eastbound 1956)- Ramona Boulevard (1961)

- Lower Azusa Road (1960)

I-605 - San Gabriel River Freeway - twin bridges (1970)

I-605 - San Gabriel River Freeway - twin bridges (1970)- Live Oak Avenue (1961)

- Arrow Highway (1949)

- Santa Fe Dam

I-210 - Foothill Freeway (1968)

I-210 - Foothill Freeway (1968)- Foothill Boulevard/Huntington Drive (1922)

- [Pedestrian Bridge]

- Mountain Laurel Way

- Rock Springs Way

SR 39 - San Gabriel Canyon Road (1933)

SR 39 - San Gabriel Canyon Road (1933)- Morris Reservoir

- San Gabriel Reservoir

East Fork Crossings

- Forest Route 2N16/Upper Monroe Rd to Fire Camp 19

- East Fork Road (1936)

- Bridge to Nowhere (1936)

North Fork Crossings

SR 39 (1967)

SR 39 (1967) SR 39 (1967)

SR 39 (1967) SR 39 (1932)

SR 39 (1932)

West Fork Crossings

- East Fork Road (1949)

- State Route 39 (1962)

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |