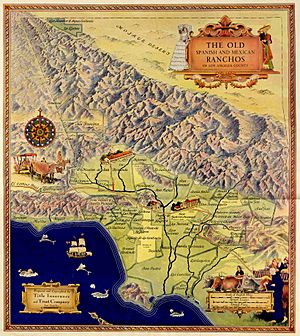

Ranchos of California facts for kids

Ranchos were large pieces of land given out by the Spanish and Mexican governments in what is now California. This happened between 1775 and 1846. These land grants helped people settle in the area.

The Spanish government first gave out "concessions" to soldiers. These lands went back to the government when the soldier died. Later, the Mexican government gave much larger land grants. These grants gave people permanent ownership. Most ranchos were along the California coast, near San Francisco Bay, and in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys.

When the government took over the Mission churches in 1833, they were supposed to give land to Native American families. However, powerful people called Californios often took these lands instead. Native Americans who lived on the ranchos often worked under harsh conditions.

Spain gave about 30 land concessions between 1784 and 1821. Mexico gave about 270 land grants between 1833 and 1846. The boundaries of these ranchos are still used today on maps and land titles. Rancho owners, called rancheros, mostly raised cattle and sheep. Many of their workers were Native Americans who had lived at the Missions.

Ranchos were usually located where there was good land for grazing animals and plenty of water. Many modern towns and areas in California still use the names of these old ranchos. For example, Rancho San Diego and Rancho Bernardo are now suburbs of San Diego.

Contents

Ranchos in the Spanish Era (1769–1821)

During Spanish rule, ranchos were like special permits. They allowed people to settle and graze animals on certain lands. But the Spanish King still owned the land.

Settlement outside of military forts (presidios), missions, and towns (pueblos) began in 1784. Juan José Domínguez was one of the first to get permission. He grazed his cattle on the large Rancho San Pedro. This rancho was about 48,000 acres (194 square kilometers).

Land was often measured in "leagues." One league of land was a square about 4,428 acres (1,792 hectares) in size.

Ranchos in the Mexican Era (1821–1846)

When Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, California came under Mexican control. During this time, people could get full legal ownership of land. New laws in 1824 and 1828 made it easier to get land grants.

These laws aimed to break up the large land holdings of the missions. They also encouraged more settlers to come to California. Mexican governors could now grant state lands. Many Spanish land concessions were then officially granted under Mexican law. Often, these went to friends of the governor.

Secularization of Missions

Soldiers, rancheros, and farmers wanted the rich coastal lands controlled by the missions. The Mexican government was also worried that the missions were still loyal to the Pope. So, in August 1833, the government took control of all the missions and their valuable lands. Each mission had about 1,000,000 acres (4,047 square kilometers) of land. The priests were only allowed to keep the church, their living quarters, and a garden. The soldiers guarding the missions were sent away.

The government said that half of the mission lands and property should go to the Native Americans who lived there. They were supposed to get 33 acres (13 hectares) of farmland and shared land for their animals. However, this rarely happened.

Most Native Americans were not prepared to take on these lands. Instead, they were often taken advantage of by the rancheros. Many ended up working for the rancheros under difficult conditions. Most mission property was bought by government officials or wealthy locals called Californios. These were people of Mexican or Spanish descent born in California.

Land Ownership and Labor

The number of Mexican land grants grew a lot after the missions were taken over. Native Americans, who were no longer forced to work at the missions, often had no land of their own. Their old way of life was gone. Some joined other Native American tribes, while others found work on the new ranchos. They sometimes gathered in living areas near the ranchos, where a mix of Spanish and Native American cultures developed.

By 1846, about 800 private landowners, the rancheros, owned the mission lands and cattle. They owned about 800 million acres (3.2 million square kilometers) of land in total. This was about one-eighth of the future state of California. These ranchos ranged in size from 4,500 acres (18 square kilometers) to 50,000 acres (202 square kilometers).

Rancheros mainly produced animal hides for the global leather market. They relied heavily on Native American labor. These workers were often tied to the rancho and treated very poorly. Native Americans working on ranchos died at twice the rate of enslaved people in the southern United States.

The boundaries of Mexican ranchos were often not very clear. New owners had to get a legal survey done to mark the boundaries. But even then, the diseño (a rough, hand-drawn map) often only vaguely showed the lines.

Owners were not allowed to divide or rent the land at first. It had to be used for grazing animals or farming. A house had to be built within a year, usually a simple adobe cabin. Public roads crossing the property had to stay open. However, these rules were often not enforced because the government didn't have enough money or organization.

Ranchos in the American Era (1846–1874)

The Mexican–American War started in May 1846. California became a U.S. territory after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in February 1848. California was then run by the U.S. military until 1849. In September 1849, a meeting was held in Monterey to create a state government. California officially became the 31st U.S. state on September 9, 1850.

The Gold Rush and Ranchos

The late 1840s brought an end to Mexican control in California. But it also started a very successful time for the rancheros. Before this, cattle were mostly raised for their hides and fat, not for meat. There wasn't a big market for beef.

However, everything changed with the Gold Rush. Thousands of miners and others rushed into northern California. They needed food, and the demand for meat made cattle prices skyrocket. This was a golden age for Hispanic California and its rancheros.

Land Claims and Challenges

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo promised that Mexican land grants would be respected. To check and confirm these land titles, American officials gathered Spanish and Mexican records.

The new leaders of California soon found that many grants had been given out just before the Americans took control. Mexican governors had rewarded loyal supporters. They also hoped to stop new American immigrants from taking over the land.

In 1851, the U.S. Congress passed a law requiring all holders of Spanish and Mexican land grants to prove their ownership to a special board. This law put the responsibility on the landowners to prove their titles were valid. The old diseños (maps) were often rough and unclear. Before the Gold Rush, land wasn't worth much, so boundaries were often vague. They might refer to a tree, a pile of rocks, or a creek.

About 588 grants were made between 1769 and 1846. These covered over 8.85 million acres (3.58 million hectares). Settling these land titles was often very difficult and took a long time. Even when boundaries were clearer, many markers had been destroyed. The Land Commission also had to decide if owners had followed Mexican laws. Mexican officials often didn't keep good records. Many grants needed more approvals to be legal, and owners were supposed to live on the land. These rules were rarely followed.

The Land Commission confirmed 604 out of 813 claims. But most decisions were appealed to higher courts. The process required lawyers, translators, and surveyors. It took an average of 17 years to resolve, including the American Civil War. This was very expensive for landowners. Many had to sell or give away parts of their land to pay for legal fees.

When land claims were rejected, it led to conflicts between the original owners, squatters, and new settlers. This put pressure on Congress to change the rules. New laws allowed squatters to claim land and buy it cheaply. Land from rejected titles became public land. It was then available to homesteaders, who could claim up to 160 acres (0.65 square kilometers) for free.

Changes and Legacy

The rancheros became rich in land but poor in cash. Defending their land claims was often too expensive. Many lost their lands because they couldn't pay their debts or legal fees. Some land was also lost due to fraud.

A big drop in cattle prices, severe floods in 1861–1862, and droughts in 1863–1864 also forced many rancheros to sell their properties to Americans. These new owners often quickly divided the land and sold it to new settlers for farming.

A new law in 1874, the "No-Fence Law," changed things for ranchers. Before, farmers had to fence their fields to keep out free-roaming cattle. After 1874, ranchers had to fence in their cattle. This was very expensive for large grazing areas. Many ranchers had to sell their cattle at very low prices.

Lasting Impact

The ranchos created land-use patterns that you can still see in California today. Many communities still have Spanish rancho names. For example, Rancho Peñasquitos is now a suburb in San Diego. Modern communities often follow the original rancho boundaries, which were based on natural features.

Today, most of the original rancho lands have been divided and sold. They have become suburbs and rural areas. Only a very small number of ranchos are still owned by the families of the original owners. Even fewer still have their original size or remain undeveloped.

Rancho Guejito in San Diego County is one of the last undeveloped San Diego Ranchos. It has only a few historic buildings and a ranch house built in the 1970s. The current owner is considering developing the land into housing, despite her parents' wishes to keep it undeveloped.

See also

In Spanish: Ranchos de California para niños

In Spanish: Ranchos de California para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |