Spanish missions in California facts for kids

The Spanish missions in California were a group of 21 religious outposts. Catholic priests from the Franciscan order built them between 1769 and 1833. They are located in what is now California, USA. The main goal was to teach Native Americans about Christianity. Spanish soldiers supported these missions. They were a key part of Spain's plan to expand its empire into the northern and western parts of Spanish North America. Along with missionaries, settlers and soldiers also created towns, like the Pueblo de Los Ángeles.

Native peoples were often forced to live in these mission settlements. This changed their traditional way of life and affected many villages. European diseases spread quickly in the crowded missions, causing many deaths. Sadly, abuse, not enough food, and overwork were common. Records show at least 87,787 baptisms and 63,789 deaths. Native peoples often resisted and did not want to convert to Christianity. Some ran away, while others started rebellions. Missionaries found it hard to make Native people truly believe in Catholicism. Young Native girls were often taken from their families and housed in special dorms called monjeríos. Many historians say the missions played a role in destroying Native culture, calling it cultural genocide.

By 1810, Spain's king was imprisoned, and money for the missions stopped. In 1821, Mexico became independent from Spain. The missions kept control over Native peoples and land until the 1830s. At their peak in 1832, the missions controlled about one-sixth of Alta California. The Mexican government then passed the Mexican Secularization Act of 1833. This act closed the missions and freed Native peoples from their control. Priests mostly returned to Mexico. The churches fell apart, and their farmlands were given to settlers, soldiers, and a few Native people.

Today, the surviving mission buildings are California's oldest structures. Many were restored in the early 1900s. They are now popular historic sites and a symbol of California. You can see them in movies and TV shows. They also inspired a style of building called Mission Revival architecture. However, historians and Native Californians have concerns. They worry about how the mission period is taught and remembered. Many of California's oldest European towns grew around or near these missions. This includes big cities like Los Angeles, San Diego, San Jose, and San Francisco.

Contents

How California Missions Were Planned

Building the Coastal Mission Chain

Before 1754, the Spanish King directly approved mission lands. But because California was so far away, he let the viceroys (governors) of New Spain approve land grants. King Charles III approved lands for the Alta California missions. He was worried about Russian fur traders along the California coast in the mid-1700s.

The missions were meant to be connected by a land route. This route later became known as the Camino Real. Friar Junípero Serra was in charge of planning these missions. He had already taken over Jesuit missions in Baja California Peninsula in 1767. After Serra died, Rev. Fermín Francisco de Lasuén started nine more missions between 1786 and 1798. Others built the last three missions and several asistencias (smaller mission outposts).

Plans for More Missions

The coastal mission chain was finished in 1823, after Serra's death in 1784. Plans to build a 22nd mission in Santa Rosa in 1827 were canceled.

In 1784, Rev. Pedro Estévan Tápis suggested building a mission on one of the Channel Islands. These islands are off San Pedro Harbor. He thought an island mission might attract new converts. It could also help stop smuggling. Governor José Joaquín de Arrillaga approved the idea. However, a measles outbreak killed about 200 Tongva Native Americans. Also, there wasn't enough land for farming or fresh water. So, no island mission was ever built.

In September 1821, Rev. Mariano Payeras visited Cañada de Santa Ysabel. This area is east of Mission San Diego de Alcalá. He planned to build a whole chain of missions inland. The Santa Ysabel Asistencia had been started in 1818 as a "mother" mission. But this larger plan never happened.

Choosing and Designing Mission Sites

The mission was one of three main ways Spain expanded its lands. The other two were the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town). Asistencias were smaller mission outposts. They held regular church services but didn't have a resident priest. Like missions, they were built where many Native people lived. Spanish Californians usually stayed near the coast when building settlements. Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad was the farthest inland, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) from the coast.

Each mission had to support itself. Supplies from Mexico were hard to get. Ships were too small to carry much food. To survive, the padres needed converted Native Americans, called neophytes. These neophytes grew crops and raised animals to feed the mission. Because imported materials and skilled workers were scarce, missionaries used simple building materials like adobe and basic methods.

Missions were meant to be temporary, but building one took a long time. It involved months or years of paperwork. Once approved, missionaries chose a site with good water, wood, and land for farming and animals. They blessed the site and built simple shelters from tree branches or reeds. These huts later became the stone and adobe buildings we see today.

The first thing built was the church (iglesia). Most churches faced east-west to get the best sunlight inside. Workshops, kitchens, living areas, and storage rooms were usually grouped in a square shape called a quadrangle. Religious events and celebrations often happened inside this area. The quadrangle was rarely a perfect square because missionaries didn't have surveying tools. They measured everything by foot. Some stories say tunnels were built for escape, but there's no proof of this.

Franciscans and Native People

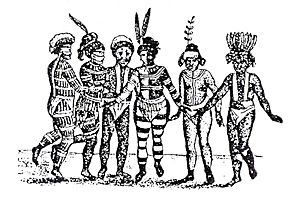

The Alta California missions were also called reductions. They were settlements built by Spanish colonizers. Their goal was to make Native people fully adopt European culture and the Catholic Church. This idea came from a 1531 rule. It said Spain had a right to the land and people if they were evangelized. Native people were gathered around the mission through forced relocation. The Spanish wanted to "reduce" them from a "wild" state to "civilized" members of colonial society. They did not value the Native cultures that had existed for thousands of years.

Between 1769 and 1845, 146 Franciscan friars, mostly from Spain, served in California. Sixty-seven died at their missions. Two were considered martyrs: Padres Luis Jayme and Andrés Quintana. The others returned to Europe due to illness or after finishing their ten-year service. Franciscan rules said friars could not live alone. So, two missionaries lived at each mission in the convento. The governor assigned a guard of five or six soldiers to each mission. These soldiers were led by a corporal who managed the mission's daily affairs under the priests' guidance.

Native people were first drawn to the missions with gifts like food, colorful beads, and cloth. Once baptized, a Native American was called a neophyte, or new believer. This happened after a short time of learning basic Catholic beliefs. Many Native people joined out of curiosity or to trade. But many found themselves trapped after baptism. However, Native people also served in mission militias and had some roles in mission leadership.

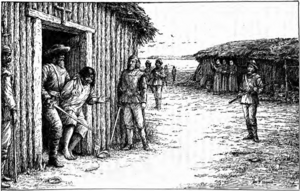

To the padres, a baptized Native person was no longer free to travel. They had to work and worship at the mission under strict rules. Priests and overseers made them attend daily masses and work. If a Native person didn't show up for duties for a few days, they were searched for. If they left without permission, they were considered runaways. Large military groups were sent to find escaped neophytes. Sometimes, Franciscans allowed neophytes to visit their home villages. But they would secretly follow them. When they found runaways, they would bring them back to the missions, sometimes 200 to 300 Native people at a time.

One account describes how soldiers went to a village. They tied and whipped everyone and forced them back to the mission. At the mission, men were told to put their bows and arrows at the priest's feet. Babies and children under eight were baptized. Babies stayed with their mothers, but older children were kept away from their parents. This led women to agree to baptism to be with their children. Eventually, men also agreed to be baptized to be with their families. Marriages were then performed.

In 1806, 20,355 Native people were living at the California missions. This was the highest number during the Mission Period. Under Mexican rule, the number rose to 21,066 in 1824. From 1769 to 1834, Franciscans baptized 53,600 adult Native Americans and buried 37,000. Historians estimate that diseases caused 15,250, or 45%, of the population decrease. Two measles outbreaks, in 1806 and 1828, caused many deaths. The death rates were so high that missions constantly needed new converts.

Young Native women had to live in the monjerío (or "nunnery"). An older Native woman supervised them and taught them. Women only left the convent after they were chosen by a Native suitor and ready for marriage. Following Spanish custom, courtship happened through a barred window. After marriage, the woman moved into a family hut outside the mission compound. Priests believed these "nunneries" were needed to protect women from men. However, the crowded and unhealthy conditions in these dorms led to quick spread of diseases and a drop in population. So many died that some Native residents urged priests to raid new villages for more women.

High Death Rates

By December 31, 1832, the missions had performed 87,787 baptisms and 24,529 marriages. They recorded 63,789 deaths. The death rate at the missions, especially for children, was very high. Most children baptized did not live past childhood. For example, at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, three out of four children died before age two.

Many things caused the high death rate at the missions. These included disease, overworking, and not enough food. Forcing Native people into crowded mission living spaces helped diseases spread quickly. While at the missions, Native people's diets changed to Spanish foods. This made them less able to fight off illnesses. Common diseases included dysentery and fevers.

Historians have compared the death rate to other terrible events. Some have said that the Franciscan priests caused Native deaths as effectively as Nazis in concentration camps.

| No. | Name | Baptisms and/or Indigenous population | Deaths and/or remaining pop. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mission San Diego de Alcalá | 6,638 baptisms total

(2,685 children) |

4,428 deaths total | From 1810 to 1820, the death rate was 77% of baptisms. Only 34 families remained after 1833. |

| 2 | Mission San Luis Rey de Francia | 5,401 baptisms total (1,862 children)

2,869 people in 1826 |

||

| 3 | Mission San Juan Capistrano | 4,317 baptisms total (2,628 children) | 3,153 deaths total | |

| 4 | Mission San Gabriel Arcángel | 7,854 baptisms total (2,459 children)

1,701 people in 1817 |

5,656 deaths total (2,916 children)

1,320 people in 1834 |

A missionary reported that three out of four children died before age 2. |

| 5 | Mission San Fernando Rey de España | 1,367 children baptized

1,080 people in 1819 |

965 children died | The high death rate sometimes made neophytes run away. |

| 6 | Mission San Buenaventura | 3,805 baptisms total (1,909 children)

1,330 people in 1816 |

626 people remaining in 1834 | About 250 people remained in 1840. |

| 7 | Mission Santa Barbara | 1,792 people in 1803 | 556 people remaining in 1834 | At this rate, the mission population would have disappeared quickly. |

| 8 | Mission Santa Inés | 757 children baptized

770 people in 1816 |

519 children died

334 people remaining in 1834 |

|

| 9 | Mission La Purísima Concepción | 1,492 children baptized total

1,520 people in 1804 |

902 children died

407 people in remaining in 1834 |

|

| 10 | Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa | 2,608 baptisms total (1,331`children)

852 people in 1803 |

264 people remaining in 1834 | |

| 11 | Mission San Miguel Arcángel | 2,588 baptisms total

1,076 people in 1814 |

2,038 deaths total

599 people remaining in 1834 |

This mission had the lowest death rate. |

| 12 | Mission San Antonio de Padua | 4,348 baptisms total (2,587 children)

1,296 people in 1805 |

567 people remaining in 1834 | |

| 13 | Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad | 2,222 baptisms total

725 people in 1805 |

1,803 deaths total

300 people remaining |

|

| 14 | Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo | 971 people in 1794, 758 in 1800, 513 in 1810, 381 in 1820 | 150 people remaining in 1834 | The Native population was quickly decreasing. |

| 15 | Mission San Juan Bautista | 1,248 people in 1823 | 850 people remaining in 1834 | This mission's population grew from 1810 to 1820. The graveyard smell was very strong. |

| 16 | Mission Santa Cruz | 2,466 baptisms total

644 people in 1798 |

2,034 deaths total

250 people remaining in 1834 |

|

| 17 | Mission Santa Clara de Asís | 7,711 baptisms (3,177 children)

927 people in 1790, 1,464 in 1827 |

150 people remaining in 1834 | The Native population dropped sharply from 1827 to 1834. |

| 18 | Mission San José | 6,737 baptisms total

1,754 people in 1820 |

5,109 deaths total | |

| 19 | Mission San Francisco de Asís | 880 deaths in 1806 alone | An epidemic in 1806 caused many deaths. | |

| 20 | Mission San Rafael Arcángel | 1,873 baptisms total

1,140 people in 1828 |

698 deaths total

Less than 500 people remaining |

|

| 21 | Mission San Francisco Solano | 1,315 baptisms total

996 people in 1832 |

651 deaths total

About 550 people remaining |

Daily Life and Work

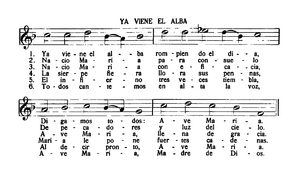

About 90,000 Native people were kept in guarded mission compounds. They were essentially forced laborers. The Franciscans wanted them to be busy all the time. Bells were very important for daily life. They rang for meals, work, religious services, births, and funerals. They also signaled ships or returning missionaries. New missionaries learned the complex bell-ringing rituals.

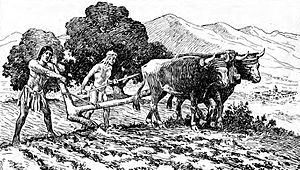

The day started with sunrise Mass and morning prayers. Then, Native people learned about the Roman Catholic faith. After a breakfast of atole (a corn drink), men and women were given their daily tasks. Women made clothes, knitted, wove, embroidered, washed, and cooked. Some stronger girls ground flour or carried heavy adobe bricks (55 pounds or 25 kg) to the men building structures. Men did many jobs. They learned to plow, plant, water, harvest, and thresh crops. They also learned to build adobe houses, tan leather, shear sheep, weave wool into rugs and clothes, and make ropes, soap, and paint.

The workday was six hours long. It included a break for lunch around 11:00 a.m. and a two-hour siesta (nap). The day ended with evening prayers, the rosary, supper, and social activities. About 90 days each year were holidays, free from manual labor. The work system at the missions was similar to a slave plantation. Visitors from other countries noted that the priests had too much control over Native people. But they also saw it as necessary because there were so few white men.

Missions operated under strict and harsh conditions. A "light" punishment could be 25 lashings. Native people were not paid wages. They were not considered free workers. Because of this, missions made profits from goods produced by the Mission Indians. Other Spanish and Mexican settlers could not compete with the missions' economic advantage.

Franciscans also sent neophytes to work for Spanish soldiers at the presidios (forts). Each presidio had land for livestock and food for soldiers. Soldiers were supposed to work this land themselves. But within a few years, neophytes did all the farm work. They also served as domestic helpers for the soldiers. Although neophytes were supposed to get wages, no one tried to collect these wages after 1790. Records show that neophytes did this work "under complete force."

Recently, there has been much debate about how priests treated Native Americans. Many believe the California mission system caused the decline of Native cultures. From the Spanish priests' point of view, they were trying to improve the lives of the "heathen" Native people.

The missionaries were generally well-meaning and devoted men. Their feelings toward Native Americans ranged from caring (though controlling) to angry. They found it hard to understand the complex and very different Native American customs. Using European standards, they criticized Native people for living in a "wilderness," for worshipping other gods, and for not having written laws, armies, forts, or churches.

Industries and Products

The main goal of the missions was to become self-sufficient quickly. So, farming was the most important industry. Barley, maize (corn), and wheat were common crops. Grains were dried and ground into flour. California is known for its many fruit trees today. But originally, only wild berries or small bushes grew fruit. Spanish missionaries brought fruit seeds from Europe. Many of these came from Asia. Orange, grape, apple, peach, pear, and fig seeds were common imports.

Grapes were grown and fermented into wine. This wine was used for religious ceremonies and for trading. The specific type, called the Criolla or Mission grape, was first planted at Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1779. In 1783, the first wine in Alta California was made there. Ranching also became important. Cattle and sheep herds were raised.

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel saw the start of California's citrus industry. The first large orchard was planted there in 1804. However, people didn't realize how much money citrus could make until 1841. Olives, first grown at Mission San Diego de Alcalá, were grown, cured, and pressed to make oil. This oil was used at the mission and traded. Rev. Serra set aside part of the Mission Carmel gardens for tobacco plants in 1774. This practice soon spread.

Missions also had to provide food and goods to the Spanish forts, or presidios. This was a constant source of disagreement between missionaries and soldiers. They argued about how much barley, how many shirts, or how many blankets the mission had to provide each year. Sometimes, these demands were hard to meet. This was especially true during droughts or when expected shipments from San Blas didn't arrive. The Spanish kept careful records of mission activities. Each year, reports were sent to the Father-Presidente. These reports summarized the material and spiritual status of each mission.

Livestock was raised for meat, wool, leather, and tallow (animal fat). Animals were also used for farming. In 1832, when they were most successful, the missions owned:

- 151,180 cattle

- 137,969 sheep

- 14,522 horses

- 1,575 mules or donkeys

- 1,711 goats

- 1,164 pigs

All these animals came from Mexico. Many Native people were needed to guard the herds on the mission ranches. This created a group of skilled horsemen. These animals multiplied more than expected. They often overran pastures and spread beyond mission lands. The large herds of horses and cows thrived in California's climate and wide pastures. But this came at a high cost for California Native Americans. The uncontrolled spread of these new herds and invasive plants quickly used up the native plants in grasslands. These were plants that Native people relied on for seeds, leaves, and bulbs. The Spanish also recognized the overgrazing problems. They sometimes killed thousands of extra livestock when herds grew too large. This also happened during severe droughts.

Mission kitchens and bakeries prepared thousands of meals daily. Candles, soap, grease, and ointments were made from tallow (rendered animal fat) in large vats. These were usually outside the west wing. Also in this area were vats for dyeing wool and tanning leather. Simple looms were used for weaving. Large bodegas (warehouses) stored preserved foods and other materials for a long time.

Each mission had to make almost all its building materials from local resources. Workers in the carpintería (carpentry shop) used simple methods to shape beams and other parts. More skilled workers carved doors, furniture, and wooden tools. For some uses, bricks (ladrillos) were fired in ovens (kilns) to make them stronger. When tejas (roof tiles) replaced traditional reed roofs, they were also hardened in kilns. Glazed ceramic pots, dishes, and containers were also made in mission kilns.

Before the missions, Native peoples only used bone, seashells, stone, and wood for building and tools. Missionaries taught them European skills and methods. These included agriculture, mechanical arts, and animal care. Everything Native people used was made at the missions under the priests' supervision. So, the neophytes not only supported themselves but also the entire military and government of California after 1811. The foundry at Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to introduce Native Americans to the Iron Age. The blacksmith used the mission's forges (California's first) to smelt iron. They made everything from basic tools and nails to crosses, gates, hinges, and even cannons for defense. Iron was a trade item, as there was no mining in the region.

The missions had extensive water supply systems. Stone zanjas (aqueducts), sometimes miles long, brought fresh water from a river or spring. Open or covered ditches and clay pipes carried water by gravity into large cisterns and fountains. The water's force turned grinding wheels and other simple machines. Water for drinking and cooking was filtered through sand and charcoal. One of the best-preserved water systems is at Mission Santa Barbara.

History

Starting in 1492 with Christopher Columbus's voyages, the Kingdom of Spain wanted to build missions. Their goal was to convert Native people in Nueva España (New Spain) to Catholicism. This included the Caribbean, Mexico, and much of the Southwestern United States. This helped Spain colonize these lands, including the area later known as Alta California.

Early Spanish Exploration

Just 48 years after Columbus, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led a large expedition from New Spain in 1540. He traveled through parts of the southwestern United States to present-day Kansas. Two years later, in 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed up the coast from Mexico. He explored Baja California and then Alta California.

Secret English Claims

Spain did not know that Sir Francis Drake, an English privateer, claimed the Alta California region for England in 1579. He called it Nova Albion. This was a generation before the first English settlement in Jamestown in 1607. During his trip around the world, Drake anchored north of present-day San Francisco. He made friends with the Coastal Miwok and claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth I. However, Drake returned to England, and England never pursued this claim.

Russian Exploration

It wasn't until 1741 that Spain's King Philip V worried about protecting his claims in Alta California. Philip was concerned when the Russian Empire explored the western coast of North America with the Vitus Bering expedition.

Spanish Expansion in California

California was the "high-water mark" of Spanish expansion in North America. It was Spain's last and northernmost colony. The mission system helped Spain control its growing lands in the New World. The Spanish government and the Church realized they needed more people in the colonies. So, they created a network of missions to convert Native people to Christianity. Their goal was to make them converts and tax-paying citizens. To do this, Native people had to learn Spanish and vocational skills, along with Christian teachings.

Estimates for the Native population in California before Europeans arrived vary greatly. They range from 133,000 to as many as 705,000 people. These numbers represent over 100 different tribes or nations.

On January 29, 1767, King Charles III ordered the new governor, Gaspar de Portolá, to remove the Jesuits by force. The Jesuits had run 15 missions on the Baja California Peninsula. Visitador General José de Gálvez then asked the Franciscans, led by Friar Junípero Serra, to take over these missions in 1768. The padres closed some missions and started new ones. This included Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá, the only Franciscan mission in Baja California. This plan changed when Gálvez received new orders: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." The Church then told the Dominican Order to take over the Baja California missions. This allowed the Franciscans to focus on building new missions in Alta California.

The Mission Period (1769–1833)

On July 14, 1769, Gálvez sent the Portolá expedition from Loreto to explore lands to the north. Gaspar de Portolá led the expedition, with Franciscans led by Junípero Serra. Serra planned to extend the missions north from Baja California. They would be connected by a road, about a day's travel apart. The first Alta California mission and fort were founded in San Diego. The second was in Monterey.

On the way to Monterey, Rev. Francisco Gómez and Rev. Juan Crespí found a Native settlement. Two young girls were dying. Gómez baptized the baby, naming her Maria Magdalena. Crespí baptized the older child, naming her Margarita. These were the first recorded baptisms in Alta California. Crespí called the spot Los Cristianos. The group continued north but missed Monterey Harbor. They returned to San Diego in January 1770. By late 1769, the Portolá expedition reached its northernmost point near present-day San Francisco. In later years, the Spanish Crown sent more expeditions to explore Alta California.

Spain also settled California with African and mulatto Catholics. This included at least ten of the recently found Los Pobladores, who founded Los Angeles in 1781.

Organization

The original plan was to turn each mission over to local priests. All mission lands would be given to the Native population within ten years. This plan was based on Spain's experience with more developed tribes in Mexico, Central America, and Peru.

However, Rev. Serra and his group realized that Native Americans in Alta California needed much more time to adapt. None of the California missions ever became fully self-sufficient. They still needed some financial support from Spain.

Financial Support

Mission development was paid for by El Fondo Piadoso de las Californias (The Pious Fund of the Californias). This fund helped missionaries spread the Catholic faith in California. It started in 1697 with donations from individuals and religious groups in Mexico to the Society of Jesus.

When the Mexican War of Independence began in 1810, support from the Pious Fund mostly stopped. Missions and converts were left to support themselves.

Native Labor

By 1800, Native labor was the backbone of the colonial economy. A severe measles epidemic occurred between March and May 1806. It killed one-quarter of the Native mission population in the San Francisco Bay Area.

In 1811, the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico sent a questionnaire to all Alta California missions. It asked about the customs, behavior, and condition of the Mission Indians. The answers varied greatly. They were collected and sent to the government. These responses, even if incomplete or biased, are valuable to modern ethnologists (people who study cultures).

Russian Settlements in California

Russian colonization of the Americas reached as far south as present-day Graton, Point Arena, and Tomales Bay. Chernyk, a farming community near Graton, was about 30 miles (48 km) from present-day Sonoma, California. It had barracks, farm buildings, fields, an orchard, and a vineyard. Their main base was Fort Ross, a farming, science, and fur trading settlement on the coast. When they hunted sea otters and seals to extinction, they failed to supply Russia's Alaskan settlements from California. So, they left the area.

Pirate Attacks

In November and December 1818, several missions were attacked by Hippolyte Bouchard, "California's only pirate." Bouchard was a French privateer sailing under the flag of Argentina. He raided installations at Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Juan Capistrano. Many mission priests and officials sought safety at Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, the most isolated mission. Ironically, Mission Santa Cruz was not attacked by pirates. Instead, local residents who were supposed to protect the church's valuables looted and vandalized it.

End of Mission Expansion

By 1819, Spain decided to limit its reach in the New World to Northern California. This was because of the high costs of supporting these distant outposts. The northernmost mission, Mission San Francisco Solano, was founded in Sonoma in 1823.

An attempt to found a 22nd mission in Santa Rosa in 1827 was stopped. In 1833, the last group of missionaries arrived in Alta California. These friars were born in Mexico, not Spain. They had been trained at the Apostolic College of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Zacatecas. Among them was Francisco García Diego y Moreno, who became the first bishop of the Diocese of Both Californias. These friars faced the biggest changes from secularization and the U.S. takeover. Many were accused of corruption.

Chumash Revolt of 1824

The Chumash people rebelled against the Spanish in 1824. The Chumash planned a coordinated uprising at three missions. An incident with a soldier at Mission Santa Inés caused the rebellion to start on Saturday, February 21. The Chumash left Mission Santa Inés when military help arrived. Then, they attacked Mission La Purisima from inside. They forced the soldiers to surrender and let them, their families, and the mission priest leave for Santa Inés. The next day, the Chumash at Mission Santa Barbara took over the mission peacefully. They fought off a military attack and then retreated to the hills. The Chumash continued to hold Mission La Purisima until a Mexican military unit attacked them on March 16. They were forced to surrender. Two military expeditions were sent after the Chumash in the hills. The first didn't find them. The second negotiated with the Chumash. Most were convinced to return to the missions by June 28.

Secularization

As Mexico became a republic, more people called for the missions to be closed down. They were finally closed in 1834. Most priests returned to Mexico. The churches stopped religious services and fell into disrepair. The farmlands were taken.

José María de Echeandía, the first Mexican Governor of Alta California, issued a "Proclamation of Emancipation" in 1826. All Native Americans in the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Monterey who were deemed ready were freed from mission rule. They could become Mexican citizens. Those who wanted to stay at the missions were mostly excused from physical punishment. By 1830, even the neophyte populations felt they could run the mission ranches and farms on their own. However, the padres doubted their abilities.

More immigration, both Mexican and foreign, put pressure on the Alta California government. They wanted to take mission properties and remove Native people, as Echeandía had ordered. Even though Echeandía's plan wasn't popular with the neophytes in the southern missions, he decided to try it on a large scale at Mission San Juan Capistrano. He appointed comisionados (commissioners) to oversee the emancipation of Native Americans. The Mexican government passed a law in 1827. It ordered all Spaniards under sixty to leave Mexican territories. Governor Echeandía, however, helped some missionaries stay in California.

When Thomas O. Larkin arrived in Monterey, California in 1832, Spanish missions, forts, towns, and a few ranches controlled the land and trade.

The lands of each mission connected to others. So, the missionaries controlled all the land along the coast. Only the forts, three towns, and a few ranches granted by the King of Spain were separate. The missionaries did not want any settlements other than the missions. They saw the forts as a necessary problem.

Governor José Figueroa (who started in 1833) first tried to keep the mission system going. But the Mexican Congress passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California in 1833. This happened when liberal Valentín Gómez Farías was in office.

The Act also allowed for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California. The money from selling mission property to private owners would pay for this.

For example, after Mexican independence, the Mexican government took Franciscan lands and closed the missions. However, this did not end the struggles for Native people. They faced more displacement and abuse under Mexican control. Most of the taken Franciscan lands were given as grants to white settlers or well-connected Mexicans. Native Californians continued to live on the land as workers.

Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to be secularized. On August 9, 1834, Governor Figueroa issued his "Decree of Confiscation." Nine other missions quickly followed, with six more in 1835. San Buenaventura and San Francisco de Asís were among the last, in June and December 1836. The Franciscans soon left most missions. They took almost everything valuable. Locals then often took materials from the mission buildings for construction. Former mission pasture lands were divided into large land grants called ranchos. This greatly increased private land ownership in Alta California.

Rancho Period (1834–1849)

The Native towns at San Juan Capistrano, San Dieguito, and Las Flores continued for some time. This was allowed by Governor Echeandía's 1826 Proclamation. It permitted some missions to become towns.

One estimate says that about 80,000 Native people lived in and around the missions when they were confiscated. Others claim the statewide population dropped to about 100,000 by the early 1840s. This was largely due to European diseases.

Pío de Jesús Pico, the last Mexican Governor of Alta California, found little money available when he took office. He convinced the assembly to pass a law allowing all mission property to be rented or sold. Only the church, a priest's house, and a courthouse building were kept. The money from sales was supposed to pay for church services. But there was no plan for how to get these funds.

After secularization, Father-Presidente Narciso Durán moved the mission headquarters to Santa Bárbara. This made Mission Santa Bárbara the home of about 3,000 original documents from the California missions. The Mission archive is the oldest library in California still run by its founders, the Franciscans. It is the only mission where they have always been present. Starting with the writings of Hubert Howe Bancroft, the library has been a center for studying the missions for over a century. In 1895, journalist and historian Charles Fletcher Lummis criticized the Secularization Act. He said:

In ten years, unless we act now, these noble buildings will be nothing but piles of adobe. We will deserve and get the scorn of all thoughtful people if we let our noble missions fall.

Lummis also noted the huge effort needed for restoration. He said it was urgent to act quickly to prevent total destruction: It is no exaggeration to say that human power could not have restored these four missions if there had been a five-year delay.

In 1911, author John Steven McGroarty wrote The Mission Play. This three-hour show described the California missions from their founding in 1769 through secularization in 1834. It ended with their "final ruin" in 1847.

Today, missions exist in different states of repair. The most common parts still standing are the church building and a nearby convento (convent) wing. In some places, like San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Soledad, the current buildings are replicas built on or near the original site. Other mission compounds are still quite complete and look like they did during the Mission Era.

A good example of a complete complex is the now-threatened Mission San Miguel Arcángel. Its chapel still has the original interior murals. These were created by Salinan Indians under the direction of Esteban Munras, a Spanish artist. This building was closed from 2003 to 2009 due to damage from the San Simeon earthquake. Many missions have preserved or rebuilt historic features besides the chapel buildings.

The missions are a big part of California's history. Tourists from all over the world visit them. To help preserve them, President George W. Bush signed the California Mission Preservation Act into law in 2004. This law provided $10 million over five years to the California Missions Foundation. This money was for projects like structural repair and saving mission art and artifacts. The California Missions Foundation is a volunteer group founded in 1998. A change to the California Constitution has also been suggested to allow state funds for restoration.

Administration

The "Father-Presidente" was the leader of the Catholic missions in Alta and Baja California.

System Father-Presidentes

- The Rev. Junípero Serra (1769–1784)

- The Rev. Francisco Palóu (acting presidente) (1784–1785)

- The Rev. Fermín Francisco de Lasuén (1785–1803)

- The Rev. Pedro Estévan Tápis (1803–1812)

- The Rev. José Francisco de Paula Señan (1812–1815)

- The Rev. Mariano Payéras (1815–1820)

- The Rev. José Francisco de Paula Señan (1820–1823)

- The Rev. Vicente Francisco de Sarría (1823–1824)

- The Rev. Narciso Durán (1824–1827)

- The Rev. José Bernardo Sánchez (1827–1831)

- The Rev. Narciso Durán (1831–1838)

- The Rev. José Joaquin Jimeno (1838–1844)

- The Rev. Narciso Durán (1844–1846)

The College of San Fernando de Mexico appointed the Father-Presidente until 1812. After that, the position was called "Commissary Prefect." This person was appointed by the Commissary General of the Indies, a Franciscan living in Spain. Starting in 1831, separate people were chosen to oversee Upper and Lower California.

Headquarters

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá (1769–1771)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1771–1815)

- Mission La Purísima Concepción*(1815–1819)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1819–1824)

- Mission San José*(1824–1827)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1827–1830)

- Mission San José*(1830–1833)

- Mission Santa Barbara (1833–1846)

† The Rev. Payeras and the Rev. Durán stayed at their home missions during their time as Father-Presidente. So, those missions became the actual headquarters. In 1833, all mission records were moved permanently to Santa Barbara.

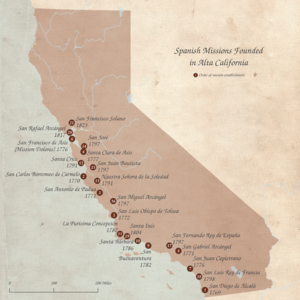

Locations

There were 21 missions with military outposts in Alta California. They stretched from San Diego to Sonoma. To make travel easier, missions were about 30 miles (48 kilometers) apart. This was about a day's journey on horseback or three days on foot. The entire path became a 600-mile (966-kilometer) long "California Mission Trail." It's said that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail to mark it with bright yellow flowers.

Following the old Camino Real northwards, from San Diego to the northernmost mission in Sonoma, California, north of San Francisco Bay, the missions were:

Forts and Military Areas

During the Mission Period, Alta California was divided into four military districts. Each district had a presidio (fort) to protect the missions and other Spanish settlements. These forts were military bases for their region. They were independent and organized from south to north:

- El Presidio Real de San Diego founded on July 16, 1769. It defended the missions at San Diego, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, and San Gabriel. This was the First Military District.

- El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara founded on April 12, 1782. It defended the missions at San Fernando, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, and La Purísima. It also defended El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río de Porciúncula (Los Angeles). This was the Second Military District.

- El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterey (El Castillo) founded on June 3, 1770. It defended the missions at San Luis Obispo, San Miguel, San Antonio, Soledad, San Carlos, and San Juan Bautista. It also defended Villa Branciforte (Santa Cruz). This was the Third Military District.

- El Presidio Real de San Francisco founded on December 17, 1776. It defended the missions at Santa Cruz, San José, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Rafael, and Solano. It also defended El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe (San Jose). This was the Fourth Military District.

- El Presidio de Sonoma, or "Sonoma Barracks," was built in 1836 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. It was part of Mexico's plan to stop Russian advances in the region. The Sonoma Presidio became the new headquarters for the Mexican Army in California. The other presidios were mostly abandoned and fell into ruin.

There was a long-standing power struggle between the church and the government. This feud started between Rev. Serra and Pedro Fages, the military governor from 1770 to 1774. Fages saw the Spanish sites as military first, religious second. This uneasy relationship lasted over sixty years. Military leaders and mission padres needed each other to survive. But they disagreed on many things. These included land rights, supplies, mission protection, soldiers' behavior, and especially the status of Native populations.

California Missions Today

Restoring the Buildings

California has the most well-preserved missions in any U.S. state. The missions are the most famous historic sites along California's coast.

- Most missions are still owned and run by parts of the Catholic Church.

- Three missions are still managed by the Franciscan Order: Santa Barbara, San Miguel Arcángel, and San Luis Rey de Francia.

- Four missions (San Diego de Alcalá, San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, San Francisco de Asís, and San Juan Capistrano) have been named minor basilicas by the Holy See. This is because of their cultural, historic, architectural, and religious importance.

- Mission La Purísima Concepción, Mission San Francisco Solano, and one remaining mission-era building of Mission Santa Cruz are owned and run by the California Department of Parks and Recreation as State Historic Parks.

- Seven mission sites are National Historic Landmarks. Fourteen are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. All are designated as California Historical Landmarks for their history, architecture, and archaeology.

Most artwork at the missions was for religious teaching. So, mission residents didn't draw their surroundings much. But visitors found them interesting. In the 1850s, artists worked as draftsmen for expeditions. These expeditions mapped the Pacific coastline and the border between California and Mexico. Many drawings were later printed in reports.

In 1875, American illustrator Henry Chapman Ford visited all 21 mission sites. He created important watercolors, oils, and etchings. His pictures helped bring back interest in California's Spanish heritage. This led to the missions being restored. In the 1880s, articles about the missions appeared in national magazines. The first books on the subject were also published. Many artists painted missions, but few did a whole series.

The missions also became popular because of Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 novel Ramona. Later, Charles Fletcher Lummis, William Randolph Hearst, and others formed the "Landmarks Club of Southern California." They worked to restore three southern missions in the early 1900s: San Juan Capistrano, San Diego de Alcalá, and San Fernando. The Pala Asistencia was also restored. Lummis wrote in 1895:

In ten years from now, unless we act quickly, these noble buildings will be nothing but a few piles of adobe. We will deserve and get the scorn of all thoughtful people if we let our noble missions fall.

Lummis also said that it was urgent to act quickly to prevent further damage. He stated: It is no exaggeration to say that human power could not have restored these four missions if there had been a five-year delay in the attempt.

Today, the missions are in various states of repair. The church building and a nearby convent wing are the most common parts still standing. In some places, like San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Soledad, the current buildings are replicas. Other mission compounds are still quite complete and look like they did originally.

A good example of a complete complex is Mission San Miguel Arcángel. Its chapel still has the original interior murals. These were created by Salinan Indians under the direction of a Spanish artist. This building was closed from 2003 to 2009 due to severe damage from an earthquake. Many missions have preserved or rebuilt historic features besides the chapel buildings.

The missions are a big part of California's history. Many tourists visit them. In 2004, President George W. Bush signed the California Mission Preservation Act. This law provided $10 million over five years to the California Missions Foundation. This money was for projects like structural repair and saving mission art and artifacts. The California Missions Foundation is a volunteer group. A change to the California Constitution has also been suggested to allow state funds for restoration.

Images for kids

-

Mission La Purísima Concepción, located northeast of Lompoc.

-

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, located south of Soledad.

-

Mission San Antonio de Padua, located northwest of Jolon.

-

Mission Santa Barbara, located in Santa Barbara.

-

Mission San Buenaventura, located in Ventura.

-

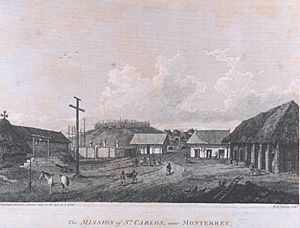

Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, located south of Carmel.

-

Mission Santa Clara de Asís, located in Santa Clara.

-

Scale replica of Mission Santa Cruz chapel, located in Santa Cruz.

-

Mission San Diego de Alcalá, located in San Diego.

-

Mission San Francisco de Asís, located in San Francisco.

-

Mission San Francisco Solano, located in Sonoma.

-

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, located in San Gabriel.

-

Mission Santa Inés, located in Solvang.

-

Mission San José, located in Fremont.

-

Mission San Juan Bautista, located in San Juan Bautista.

-

Mission San Juan Capistrano, located in San Juan Capistrano.

-

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, located in San Luis Obispo.

-

Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, located in Oceanside.

-

Mission San Miguel Arcángel, located in San Miguel.

-

Mission San Rafael Arcángel, located in San Rafael.

See Also

In Spanish: Misiones españolas en California para niños

In Spanish: Misiones españolas en California para niños

On California Missions:

- List of Spanish missions in California

- San Antonio de Pala Asistencia, not a full mission, but still serving the Pala reservation

On California history:

- Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail

- History of California through 1899

- History of the west coast of North America

- Mission Vieja

On general missionary history:

- Catholic Church and the Age of Discovery

- History of Christian Missions

- List of the oldest churches in Mexico

- Missionary

On colonial Spanish American history:

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |