Mission Santa Barbara facts for kids

The capilla (chapel) at Mission Santa Barbara.

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | 2201 Laguna St. Santa Barbara, California 93105 |

|---|---|

| Name as founded | La Misión de La Señora Bárbara, Virgen y Mártir |

| English translation | The Mission of the Lady Bárbara, Virgin and Martyr |

| Patron | Saint Barbara of Greece |

| Nickname(s) | "Queen of the Missions" |

| Founding date | December 4, 1786 |

| Founding priest(s) | Father Fermín Lasuén |

| Built | 1820, 1925 (repair) |

| Architect | Ripoll, Father Antonio |

| Architectural style(s) | Colonial, Other, Spanish colonial |

| Founding Order | Tenth mission |

| Headquarters of the Alta California Mission System | 1833–1846 |

| Military district | Second |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) |

Chumash Barbareño, Canaliño |

| Native place name(s) | Xana'yan |

| Baptisms | 5,556 |

| Marriages | 1,486 |

| Burials | 3,936 |

| Secularized | 1834 |

| Returned to the Church | 1865 |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles |

| Current use | Parish Church |

| Designated | October 15, 1966 |

| Reference no. | 66000237 |

| Designated | October 9, 1960 |

| Reference no. |

|

| Website | |

| http://www.santabarbaramission.org | |

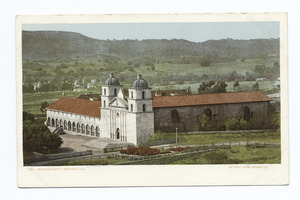

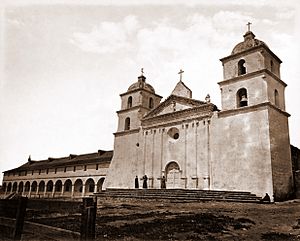

Mission Santa Barbara (Spanish: Misión de Santa Bárbara) is a historic Spanish mission located in Santa Barbara, California, United States. It is often called the 'Queen of the Missions'. Father Fermín Lasuén established it for the Franciscan order on December 4, 1786. This date was the feast day of Saint Barbara, who the mission is named after. It was the tenth of what would become 21 missions in Alta California.

Mission Santa Barbara was built as part of Spain's plan to strengthen its presence in Alta California. Spain wanted to teach local Chumash people new skills and the Christian faith. This also meant integrating them into the Spanish way of life and economy. Life changed a lot for the local Chumash people. The mission's large animal herds changed their environment, and new diseases arrived. Because of these big changes, many Chumash people found it necessary to live and work at the mission.

The city of Santa Barbara and Santa Barbara County are named after the mission. The name comes from the legend of Saint Barbara, a girl who was said to have been martyred for her Christian faith.

The mission sits on a hill between the Pacific Ocean and the Santa Ynez Mountains. Father Fermín Lasuén, who became the head of the California missions after Father Junípero Serra passed away, dedicated the site. Mission Santa Barbara is one of only two missions that have always been led by Franciscan Friars since its beginning. Today, it serves as a parish church for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

Contents

Discover Mission Santa Barbara

Building the Mission: From Chapels to Stone Walls

The early missionaries built three different chapels in the first few years. Each new chapel was larger than the one before it. In 1787, the first chapel was a simple structure made of logs with a grass roof and an earthen floor. It was about 39 feet (12 meters) long and 14 feet (4 meters) wide.

In 1789, a second chapel was built using adobe bricks and roof tiles. This one was larger, measuring about 83 feet (25 meters) long and 17 feet (5 meters) wide. From 1793 to 1794, it was replaced by a third adobe chapel with a tiled roof. This chapel was even bigger, about 125 feet (38 meters) long and 26 feet (8 meters) wide. Sadly, a strong earthquake in Santa Barbara on December 21, 1812, destroyed this third chapel.

Construction of the fourth and current mission church began around 1815 and was mostly finished by 1820. Historians believe master stonemason José Antonio Ramiez likely guided the work. Chumash people provided the labor for this large project.

The church's towers were badly damaged during another earthquake on June 29, 1925. However, strong buttresses (support structures) helped keep the main walls standing. Restoration work started the next year. By 1927, the church was carefully rebuilt to look like its original design, using similar materials for the walls, columns, and arches.

Later, it was found that the concrete foundation was weakening, causing cracks in the towers. So, between 1950 and 1953, the front facade and towers were taken down and rebuilt again. They were made to perfectly match their original look. The inside of the church has mostly stayed the same since 1820.

You can still see parts of the mission's original water system and other buildings. These were mainly built by the Chumash people under the guidance of the Franciscans. These ruins are now part of Mission Historical Park. They include vats for tanning leather, a pottery kiln (oven), and a guard house. The water system was very advanced, with aqueducts, a filtration system, and two reservoirs. It even had a water-powered gristmill for grinding grain.

The larger reservoir, built in 1806 by damming Mission Canyon, supplied water to the city until 1993. Near the mission entrance, the original fountain and lavadero (a washing area) are also still intact.

Life at the Mission: Chumash People and New Ways

Mission Santa Barbara was a key part of Spain's plan to secure its claim on Alta California. The goal was to introduce the local Chumash people to Catholicism and new ways of life. They were also taught skills to become part of the Spanish colonial economy.

The main economic activities at the missions in the Chumash region were raising animals and making products like hides and tallow (animal fat). The Santa Barbara Mission had a large herd, often over 14,000 animals between 1806 and 1810. Many Chumash workers were needed to care for these animals and help with other mission tasks.

At the same time, these large herds changed the Chumash people's traditional hunting and gathering practices. New European diseases also arrived, against which the Chumash had no natural protection. These factors made life very difficult for the Chumash. Because of these big changes, many Chumash people found it necessary to live and work at the mission. The mission introduced a new way of life and rules, and people lived and worked there, often needing permission to leave.

In 1818, two ships from Argentina, led by a French privateer named Hipólito Bouchard, approached the coast. They seemed to threaten Santa Barbara. The padres, especially Fray Antonio Ripoll, helped train and organize about 180 Chumash people to defend the mission. They formed an infantry unit with archers and people with machetes, and a cavalry unit with lancers. Father Ripoll called them the "Compañía de Urbanos Realistas de Santa Bárbara." With their help, the soldiers from the Presidio faced Bouchard. He then sailed away without attacking.

Challenges and Changes for the Chumash Community

In 1803, about 1,792 Chumash people lived at the mission in 234 adobe huts. This was the highest number living there in one year. By 1820, the Chumash population at the mission had decreased to 1,132. Three years later, it dropped further to 962.

In 1824, some Chumash people, led by Andrés Sagimomatsee, protested the mission system. This event is known as the Chumash revolt of 1824. During this time, the mission was briefly taken over. The soldiers stationed there were disarmed and sent back to the Presidio. After a conflict with troops from the Presidio, many Chumash left the mission. Some went over the Santa Ynez Mountains, and about fifty others traveled to Santa Cruz Island in plank canoes.

For a few months, the mission had very few Chumash people. Then, an agreement was made for their return by Father Presidente Vicente Francisco de Sarría and Father Antonio Ripoll. Many Chumash people returned to the mission after these discussions. However, the Chumash population continued to decline. By 1854, records show that only a few Chumash people remained near the mission.

The Chumash population at the missions faced many challenges. These included new diseases and changes to their traditional way of life, which led to a decline in their numbers.

Mission Santa Barbara After Spanish Rule

After Mexico gained independence from Spain, the Mexican government passed a law in 1833 to change how the missions were run. This process is called secularization. It meant the missions would no longer be controlled by the Franciscan order. Father Presidente Narciso Durán moved the mission headquarters to Santa Barbara. This made Mission Santa Barbara the home for about 3,000 important historical documents from various California missions.

In 1840, the Catholic Church reorganized its areas in California. Bishop Francisco Garcia Diego y Moreno made Mission Santa Barbara his main church, or cathedra. This meant the mission chapel served as a pro-cathedral (a temporary main church) until 1849. Later, from 1853 to 1876, it again served as a pro-cathedral for other dioceses. This is why Mission Santa Barbara is the only California mission chapel with two matching bell towers. At that time, only a main cathedral church usually had this architectural feature.

On March 18, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln returned the missions to the Catholic Church. At that time, the mission's leader, Friar José González Rubio, had discussions with Bishop Amat about whether the mission should belong to the Franciscan order or the diocese. Bishop John J. Cantwell finally gave the deed to the Franciscans in 1925.

As a center for the Franciscans, the mission played a big role in education in the late 1800s and early 1900s. From 1854 to 1885, it was an apostolic college. From 1869 to 1877, it also served as a college for non-clergy students. This made it Santa Barbara's first institution for higher education. In 1896, this educational effort led to a high school seminary program. This program became a separate institution, Saint Anthony's Seminary, in 1901. In 1929, the college program moved to Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. It became San Luis Rey College from 1950 to 1968 before moving to Berkeley, California. Today, it is known as the Franciscan School of Theology (FST).

Mission Santa Barbara Today: A Living Landmark

The city of Santa Barbara first grew between the mission and the harbor, near El Presidio Reál de Santa Bárbara. This was about a mile southeast of the mission. As the city expanded, it spread across the coastal plain. Now, a residential area surrounds the mission. Nearby are public parks like Mission Historical Park and Rocky Nook Park. You can also find public buildings like the Natural History Museum in the area.

Mission Santa Barbara today includes a gift shop, a museum, a Franciscan Friary (where friars live), and a retreat house. The mission grounds are a popular place for tourists to visit. The Franciscan Province of Santa Barbara owns the mission. The local parish church rents the church building from the Franciscans. For many years, Father Virgil Cordano, OFM, served as the pastor of St. Barbara's Parish, which is located on the mission grounds. He passed away in 2008. Since the summer of 2017, the mission has also been a training center for new Franciscan Friars from English-speaking regions.

The mission also houses the Santa Barbara Mission-Archive Library. This library collects and protects historical and cultural items. These items relate to Franciscan history, the missions, and the communities they interacted with. This is especially true for areas like Colonial New Spain, Northwestern Mexico, and the Southwestern United States. The library's collections began in the 1760s with Fray Junipero Serra's plans for missions in Alta California.

The collections include special sections like the Junipero Serra Collection (1713–1947) and the California Mission Documents (1640–1853). There is also the Apostolic College collection (1853–1885). The Archive-Library has many early California writings, maps, and images. It also has materials about the Tohono O'oodham Indians of Arizona. Since the time of Hubert Howe Bancroft's writings, the library has been a key place for studying mission history for over a century. It is an independent, non-profit educational and research center. It is separate from Mission Santa Barbara but uses part of the mission complex. Some Franciscans, along with scholars and community members, serve on its Board of Trustees. A lay academic scholar directs the institution.

The mission also has the longest continuous tradition of choral singing among all the California Missions. In fact, it's the oldest such tradition of any California institution. Two choirs, the California Mission Schola and the Cappella Barbara, perform during the weekly Catholic services. The mission archives hold one of the richest collections of colonial Franciscan music manuscripts known today. These are carefully preserved and many are still being studied by scholars.

Gallery

See also

- Spanish missions in California

- List of Spanish missions in California

- List of Catholic cathedrals in the United States

- List of cathedrals in the United States

- USNS Mission Santa Barbara (AO-131) – a Mission Buenaventura Class fleet oiler built during World War II.

- History of Santa Barbara, California

- California Historical Landmarks in Santa Barbara County, California