Mexican secularization act of 1833 facts for kids

The Mexican Secularization Act of 1833 was a law passed by the Mexican government. It officially took control of the Californian missions away from the Franciscan Order of the Catholic Church. This meant the missions and their lands now belonged to the Mexican government.

This law was passed 12 years after Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821. Mexico worried that Spain still had too much power in California, especially because many missions were still loyal to the Catholic Church in Spain. As Mexico became a stronger country, more people wanted the missions to be "secularized." This meant separating them from church control. Once the law was fully put into action, much of the mission land was sold or given away as large properties called ranchos.

Contents

What Were the Missions?

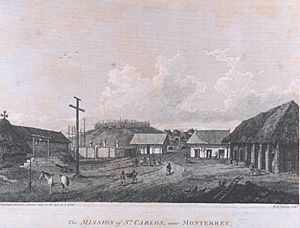

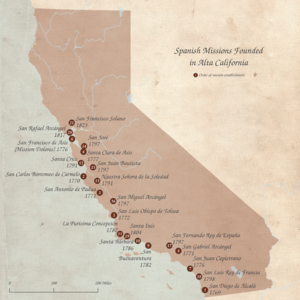

The Spanish missions in Alta California were 21 religious and military outposts. Catholic priests from the Franciscan order built them between 1769 and 1823. Their main goal was to spread Christianity among the local Native Americans.

These missions were part of Spain's first big effort to settle the Pacific Coast. This was the northernmost part of Spain's lands in North America. The settlers brought European fruits, vegetables, cattle, horses, and new farming methods to California. They also introduced new technologies to the Mission Indians. The El Camino Real road connected the missions from San Diego all the way to Mission San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, a distance of about 529 miles.

Between 1683 and 1834, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries built many religious outposts. These stretched from what is now Baja California and Baja California Sur into present-day California.

Freedom for Native Americans

José María de Echeandía was the first Mexican-born governor of Alta California. On July 25, 1826, he announced a "Proclamation of Emancipation." This meant that Native Americans in certain areas, like San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Monterey, could be freed from mission control. They could even become Mexican citizens if they qualified.

Those who wanted to stay under mission guidance were protected from most forms of physical punishment. By 1830, even new settlers in California felt confident that Native Americans could run the mission farms on their own. However, the priests (padres) disagreed. In 1831, about 18,683 Native Americans were still under mission control in Upper California. There were only about 4,342 soldiers, free settlers, and others.

More people moving to California, both from Mexico and other countries, put pressure on the government. They wanted the Church-controlled mission lands to be taken over and given to the Native Americans, as Echeandía had suggested. Even though Echeandía's plan didn't get much support from new settlers in the southern missions, he still wanted to try it on a large scale at Mission San Juan Capistrano. He appointed special commissioners (comisionados) to help free the Native Americans.

On December 20, 1827, the Mexican government passed a law. It said that all Spaniards under 60 years old had to leave Mexican lands. Spain did not recognize Mexico's independence and wanted to take back its former colony. Governor Echeandía, however, helped some Franciscans stay in California, preventing their deportation.

The Secularization Law Takes Effect

José Figueroa became governor in 1833. At first, he tried to keep the mission system as it was. But after the Mexican Congress passed its Decree for the Secularization of the Missions of the Californias on August 17, 1833, he had to act.

In 1833, Figueroa replaced the Spanish-born Franciscan priests at all missions north of Mission San Antonio de Padua. He brought in Mexican-born Franciscan priests instead. Because of this, Father-Presidente Narciso Durán moved the main office of the Alta California Mission System to Mission Santa Barbara. It stayed there until 1846.

Land Not Given to Native People

On August 9, 1834, Governor Figueroa issued a new rule. It explained how mission property (land, cattle, and tools) should be given to the Native Americans who lived at the missions. The rules said that each family head and anyone over 20 years old would get a piece of land. This land would be between 100 and 400 varas square (about 7 to 28 acres). They would also get half of the livestock and half or less of the tools and seeds.

The law also allowed for new settlements in both Alta California and Baja California. The money from selling mission land and some buildings to private owners would pay for these new settlements. Many people started ranches on these former mission lands. These ranches were very large and greatly increased the number of private landholdings in Alta California.

This meant the missions would only own the church building, the priests' homes, and a small area around the church for gardens. At some missions, all other buildings were lost. Some mission buildings were even divided by new walls. Without support from the surrounding land and buildings—like livestock, orchards, barns, and workshops—the Franciscans had no way to support themselves or the Native Americans.

The Franciscans soon left most of the missions, taking almost everything valuable with them. After they left, local people often took materials from the mission buildings for their own construction. The few soldiers assigned to guard each mission were also dismissed.

Mission Lands Taken Away

Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first mission to have its land taken away. Governor Figueroa issued his "Decree of Confiscation" on August 9, 1834. Nine other missions quickly followed, and six more in 1835. San Buenaventura and Mission San Francisco de Asís were among the last, losing their land in June and December 1836.

The land of Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad was sold, and over time, all its buildings became ruins. In 1859, the ruins and 42 acres of land were given back to the Church. Restoration work only began in 1954.

In 1838, Mission San Juan Capistrano was sold for a very low price. It was bought by Englishman John (Don Juan) Forster (who was Governor Pío Pico's brother-in-law) and his partner. Forster's family lived in the friars' quarters for 20 years. More families later moved into other parts of the mission buildings.

Father José María Zalvidea left San Juan Capistrano around November 25, 1842. This left the mission without a resident priest for the first time. The first non-missionary priest arrived on October 8, 1843. The mission's ruins and 44.40 acres were returned to the Church in 1865.

Mission San Diego de Alcalá and some other missions were offered for sale to citizens. Some mission land was given to former military officers who fought in the War of Independence. On June 8, 1846, Governor Pío Pico gave Mission San Diego de Alcalá to Santiago Argüello for his service to the government. After the United States took over California, the mission was used by the military from 1846 to 1862.

Most of the land grants went to wealthy "Californios" (people of Spanish background born in California). They had long wanted the large landholdings of the missions. In 1845, Governor Pío Pico took the lands of Mission San Diego de Alcalá. He gave a huge area (about 48,800 acres) of the El Cajon Valley to Dona Maria Antonio Estudillo. This was to pay off a $500 government debt. This land is now parts of El Cajon, Santee, Lakeside, and La Mesa. In 1862, the 22 acres and mission ruins were returned to the Church by the U.S. government.

Mission San Buenaventura was rented out in 1845 and later sold. The church, clergy residence, cemetery, orchard, and vineyard were returned to the Church in 1862. Major changes were made in 1893.

At Mission Santa Clara de Asís, the land was sold off in 1836. However, most buildings continued to be used as a church. In 1851, the Jesuits took over running the church from the Franciscans. The Jesuits founded a college there, which later became Santa Clara University.

The land of Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo was sold off in 1834. The priests had to buy back a small strip of land just to enter the church without trespassing. Later, all the buildings were abandoned and became ruins. The mission ruins and 9 acres were returned to the Catholic Church in 1859.

Mission San Antonio de Padua was put up for sale, but no one wanted to buy it. However, the fear of being sold caused the mission to fall into neglect. Father Doroteo Ambris, a young priest from Mexico, began living at the mission with a few Native Americans in 1851. On May 31, 1863, the mission was returned to the Church with 33 acres by an order signed by Abraham Lincoln.

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel was sold to American settlers. The money was used to pay off Governor Pico's debt. The mission was returned to the Franciscans in 1843.

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa was sold in 1845 by Pico. Everything except the church chapel was sold for $510 (which was worth about $70,000 in 1845). The mission was returned in 1859.

At Mission San Francisco de Asís, the mission lands were sold off in 1845. The main mission buildings and courtyard were sold or leased to businesses. This helped maintain the mission, and it was returned in 1857.

At Mission Santa Barbara in 1835, all the land was sold or given away. However, the mission buildings remained under the control of the Catholic Church and became a local church. On August 17, 1833, Father Presidente Narciso Durán moved the Missions' headquarters to Santa Barbara. This made Mission Santa Barbara the home of about 3,000 original documents from the California missions.

Mission Santa Cruz land was sold or given away in 1834. All 32 buildings were looted, and the church was left in ruins. In 1859, President Buchanan returned Mission Santa Cruz and 17 acres to the Church.

At La Purísima Mission, all land and buildings were sold in 1845. The church turned to ruins over time. The ruins were returned to the Church in 1874.

Mission San José was sold to private owners in 1845 for $12,000. All buildings decayed, and the land was not used. Native people who were supposed to get the land had fled and found it hard to return to their old way of life. In 1858, the mission ruins and 28 acres of land were returned.

At Mission San Juan Bautista, the land was sold off. But the nearby town of San Juan supported the Church, so it did not fall into decay. Services continued without stopping. In 1859, the remaining buildings and 55 acres of land were given back.

The land of Mission San Miguel Arcángel was sold off. The William Reed family lived in the buildings until 1848. Then the mission was closed and began to decay. In 1859, the mission ruins were returned, but no priest was sent there. In 1878, the Catholic Church sent priests, and restoration began.

Mission San Fernando Rey de España had its land sold off in 1834. The mission buildings were used as military headquarters by Governor Pico and John C. Frémont. In 1861, the mission buildings and 75 acres of land were returned. The buildings were falling apart because settlers took beams, tiles, and nails from the church. The buildings had been rented to businesses and even used as a hog farm. San Fernando's church did not become a working church again until 1923.

Mission San Luis Rey de Francia was sold in 1834 to private owners. But in 1846, U.S. Army troops under Captain Frémont occupied it. Some mission buildings, in poor condition, and 65 acres of land were returned in 1865.

Mission Santa Inés land was sold off in 1836, with some buildings rented out by the government. The mission had been divided, with priests living in one part and keeping a chapel. In late 1843, the Governor gave 350,000 acres to Bishop Francisco García Diego to start the College of Our Lady of Refuge, California's first college. In 1846, the college moved, and the land was sold. The college was abandoned in 1881, and by then, the mission buildings were falling apart. Some of the mission property was returned to the Church in 1862.

Mission San Rafael Arcángel was looted by Governor Mariano Vallejo. He took much of the livestock, equipment, and supplies, and some fruit trees, to his ranch. The mission was abandoned by 1844. The empty buildings were sold for $8,000 in 1846. The empty mission was briefly used by John C. Fremont as his headquarters. Six-and-a-half acres of land were returned in 1855, all in ruins. Instead of rebuilding, the mission ruins were sold to a carpenter in 1861, who tore down the church ruins. In 1869, the land was bought back, and a new gothic architecture church was built on the site.

Mission San Francisco Solano, the last and northernmost mission, was also the only one built after Mexican independence. The Governor wanted a Mexican presence north of the San Francisco Bay to keep out the Russians who had built Fort Ross. In July 1835, General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo took over Mission San Francisco Solano. At first, he gave some land to the Native American mission workers as ordered. But later, he transferred all the land and buildings to his own large ranch. Vallejo planned the town of Sonoma in 1835. He made a large plaza in front of the old mission chapel. But then he took roof tiles from the church for his own house. The mission church, now in very poor shape, was torn down. Needing a church for the town he created, Vallejo had a small chapel built in 1841 where the original church had been. On June 14, 1846, American settlers took over Sonoma and declared a "California Republic." General Vallejo was taken prisoner, and the Bear Flag was raised. The Bear Flag flew over Sonoma until July 9, 1846, when California became part of the USA.

Smaller Missions Also Affected

Besides the 21 main missions, there were also "sub-missions." These were smaller stops for travelers on the El Camino Real road. These small sub-missions were also lost:

Santa Ysabel Asistencia became a ranch. The church turned into ruins. Three acres of the original area were returned to the Church. A new chapel began construction on September 14, 1924.

San Antonio de Pala Asistencia and Las Flores Estancia were sold off in 1846. The church remained open. But on Christmas Day 1899, an earthquake shook the Pala Valley, causing the church roof to collapse. In 1902, a group bought Pala Mission. The next year, they gave ownership back to the Catholic Church and saved the chapel and a few rooms from complete ruin.

Santa Margarita de Cortona Asistencia was sold to a ranch. A few ruins are still on the private property of the Santa Margarita Ranch.

San Pedro y San Pablo Asistencia was sold to a ranch. Today, little remains. There is a plaque in Sanchez Adobe Park showing the former building's layout.

San Bernardino de Sena Estancia, sold to a ranch, is now called "Asistencia" and is part of the San Bernardino County Museum.

Diego Sepúlveda Adobe, sold to a ranch, is now a local history museum.

Las Flores Estancia was sold to a ranch. All original buildings are gone after years of neglect. The current Las Flores Adobe was built in 1865.

Nuestra Señora Reina de los Ángeles Asistencia was a sub-mission opened by the San Gabriel Mission. It served new settlers in the growing town of El Pueblo de Nuesta Señora Reina de los Ángeles. As the town grew, it built its own church, now known as the Old Plaza Church. With Mexican secularization, the Ángeles Asistencia fell into disuse. There is little physical evidence of it remaining today.

Local people increasingly disliked the governors sent from distant Mexico City. These governors often knew little about local conditions. This led to conflict in 1836, when Juan Bautista Alvarado, born in Monterey, led a revolt and took over as governor. Alvarado's actions started a period where California largely governed itself. The weak Mexican government had to allow more freedom in its far-off region. Other local governors followed, including Carlos Antonio Carrillo and Pío Pico. The last governor not from California was Manuel Micheltorena, who was forced out after another rebellion in 1845. Micheltorena was replaced by Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, who served until 1846.

The Rancho Period

It was during the Mexican era in California (1821–1846) that individuals began to receive official ownership of land plots. California, now under Mexican control, allowed people to ask for land grants. By 1828, the rules for creating land grants were written down. These laws broke up the large mission landholdings. They also made it easier to get land grants, which encouraged more settlers to come to California.

The process included a diseño, which was a hand-drawn map to show the area. The Mexican governors of Alta California gained the power to give out state lands. Many Spanish land claims were later confirmed under Mexican law, often given to the governor's "friends." A commissioner would manage the mission's crops and animals. The land was then divided into shared pastures, a town plot, and individual plots for each Native American family.

Without the strict control of the Franciscan friars and the soldiers who kept them from leaving, the Mission Indians soon left the fields (even if they were given land). They joined other tribes or looked for work on the new ranches and growing towns.

The number of Mexican land grants greatly increased after the missions were secularized in 1834. The original idea was for the land to be divided among the surviving Mission Indians. However, most of the grants went to local Californios. A small number of Native Americans did receive land grants in the 1840s, but they lost all of them by the 1850s.

California Becomes a State

The United States declared war against Mexico on May 13, 1846. Fighting in California began with the Bear Flag Revolt on June 15, 1846. On July 7, 1846, U.S. forces took control of Monterey, the capital of California. This ended the power of Mexican officials that day. Armed resistance in California ended with the Treaty of Cahuenga signed on January 13, 1847.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war, was signed on February 2, 1848. California then became a territory of the United States. The treaty gave residents one year to choose if they wanted to be American or Mexican citizens. More than 90% chose American citizenship, which included full voting rights. The other 10% either returned to Mexico (where they received land) or, in some cases in New Mexico, were allowed to stay as Mexican citizens.

Between 1847 and 1849, the U.S. military ran California. A constitutional convention met in Monterey in September 1849 and set up a state government. It operated for 10 months before California was allowed into the Union as the 31st State. This happened as part of the Compromise of 1850, on September 9, 1850.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo stated that the Mexican land grants would be honored. To check and confirm land titles in California, American officials got the old records from the Spanish and Mexican governments in Monterey.

In 1851, the United States Congress passed a law to "Ascertain and Settle Private Land Claims in the State of California." This law required everyone who held Spanish and Mexican land grants to show their titles to the Board of California Land Commissioners for confirmation. This was different from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, as it put the responsibility on the landholders to prove their ownership.

In many cases, the land grants had been made without clear boundaries. Even when boundaries were more specific, many markers had been destroyed before accurate surveys could be done. Besides unclear survey lines, the Land Commission also had to decide if the landholders had followed the rules of Mexican colonization laws.

While the Land Commission confirmed 604 out of 813 claims, most decisions were appealed to the U.S. District Court and some even to the Supreme Court. This confirmation process needed lawyers, translators, and surveyors. It took an average of 17 years to complete (including the American Civil War, 1861–1865). It was very expensive for landholders to defend their titles in court. Often, they had to sell their land to pay for legal fees or give land to their lawyers instead of money.

Land from titles that were not confirmed became public land. This land was then available for homesteaders, who could claim up to 160-acre plots under federal homestead law. When land claims were rejected, the claimants, squatters, and settlers pushed Congress to change the rules. Under a law from 1841, owners could "preempt" their parts of the grant and buy the title for $1.25 an acre, up to a maximum of 160 acres. Starting with Rancho Suscol in 1863, special laws were passed by Congress. These allowed certain claimants to buy their land without limits on acreage. By 1866, this special right was given to all owners of rejected claims.

Abraham Lincoln and Mission Ownership

In 1853, Bishop Joseph Alemany began asking the U.S. Public Land Commission to return some of the Church's land and buildings. Alemany asked for the return of the church chapel, priests' homes, cemetery, orchard, and vineyard to the Catholic Church.

After reading a letter from Alemany, President Abraham Lincoln signed a proclamation on March 18, 1865. This was just three weeks before Lincoln's assassination. The proclamation gave ownership of some mission property back to the Roman Catholic Church. Official documents for each mission were given to Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany based on his claim filed in 1853. In total, about 1,051 acres of mission land were returned.

The government also returned two large ranches: Rancho Cañada de los Pinos in Santa Barbara County, which was about 35,499 acres, and La Laguna in San Luis Obispo County, about 4,157 acres.

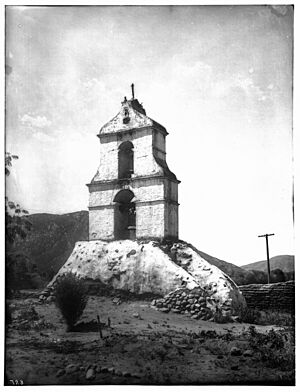

When the missions were given back to the Church, almost all of them were in ruins. Restoration of the old mission buildings then began. Abraham Lincoln had hoped to visit California, but he never got the chance. The Church was overwhelmed by how ruined many of the mission churches were. They couldn't start repairs and maintenance on all 21 missions at once. So, some missions continued to decline until restoration could begin. Most buildings were made of sun-dried adobe bricks. Without a good roof, rain would quickly turn the adobe back into mud. The historical importance of the missions was slowly recognized by many restoration groups, and work continues on the missions to this day.

Current Status of the Missions

Only two buildings in the chain of 21 Missions started by Father Serra survived mostly intact. These are the chapel at Mission San Francisco de Asís (also called Mission Dolores), built in 1791, and the Mission San Juan Capistrano chapel, built in 1782, which is the oldest building in California still in use.

The missions were restored using old photos, paintings, drawings, and the remains of building walls and foundations.

Towns grew up around each of the 21 missions, except for one: Mission San Antonio de Padua. Mexican Governor Pío Pico declared all mission buildings in Alta California for sale, but no one bid for Mission San Antonio. The mission is now surrounded by the Fort Hunter Liggett Military Reservation. The U.S. Army bought this land from the Hearst family during World War II to train troops. More land was bought from the Army in 1950 to make the mission area larger, over 85 acres. The fort still actively trains troops today and surrounds the mission. This is the only mission where you can still see some of the surrounding mission support buildings and artifacts.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ley de secularización mexicana de 1833 para niños

In Spanish: Ley de secularización mexicana de 1833 para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |