Mission San Juan Capistrano facts for kids

|

Mission San Juan Capistrano

|

|

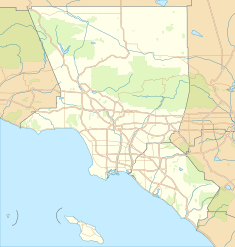

| Location | 26801 Ortega Hwy. San Juan Capistrano, California 92675 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33°30′10″N 117°39′46″W / 33.50278°N 117.66278°W |

| Name as founded | La Misión de San Juan Capistrano de Sajavit |

| English translation | The Mission of Saint John Capistrano of Sajavit |

| Patron | Saint John of Capestrano |

| Nickname(s) | "Jewel of the Missions" "Mission of the Swallow" "Mission of the Tragedies" |

| Founding date | November 1, 1776 it was the 7th mission. |

| Founding priest(s) | Fermín Lasuén (1st) Father Presidente Junípero Serra and Gregório Amúrrio (2nd) |

| Founding Order | Seventh |

| Military district | First |

| Native tribe(s) Spanish name(s) |

Acjachemen Juaneño |

| Native place name(s) | Quanís Savit, Sajavit |

| Baptisms | 4,340 |

| Confirmations | 1,182 |

| Marriages | 1,153 |

| Burials | 3,126 |

| Neophyte population | 900 |

| Secularized | 1833 |

| Returned to the Church | 1865 |

| Governing body | Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange |

| Current use | Chapel / Museum |

| Designated | September 3, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 71000170 |

| Reference no. | #200 |

| Website | |

| http://www.missionsjc.com | |

Mission San Juan Capistrano is a famous Spanish mission located in San Juan Capistrano, California. Spanish Catholic missionaries from the Franciscan Order founded it on November 1, 1776. The mission was named after Saint John of Capistrano.

This mission was once part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and was built near the village of Acjacheme. The Mexican government took control of the mission in 1833. Later, in 1865, the United States government returned it to the Roman Catholic Church. Over the years, natural disasters damaged the mission. However, people have worked to restore and fix it since about 1910. Today, it serves as a museum.

Contents

Welcome to Mission San Juan Capistrano

The mission was started in 1776 by Spanish Catholics. It was named after Saint John of Capistrano, a priest from the 1300s. Mission San Juan Capistrano is special because it has the oldest building in California that is still in use. This building is a chapel built in 1782.

This chapel, known as "Father Serra's Church," is the only place where Junipero Serra is known to have held Mass. The mission is one of the most famous in Alta California. It is also one of the few missions that was actually founded twice. The first attempt to start the mission was in 1775, but it was quickly stopped due to problems with the local people.

The mission grew a lot over time. Before the missionaries arrived, about 550 Acjachemen people lived here. By 1790, about 700 Mission Indians lived at the mission. Just six years later, nearly 1,000 "neophytes" (new converts) lived there. Between 1776 and 1847, a total of 4,639 people were baptized.

More than 69 former residents, mostly Juaneño Indians, are buried in the mission's cemetery. St. John O'Sullivan, a priest who worked hard to save and rebuild the mission, is also buried there. A statue honors him at the cemetery entrance. Three other priests who served at the mission are buried under the floor of the chapel.

The "Mission grape" was first planted here in 1779. In 1783, the first wine made in Alta California came from this mission.

After the Mexican government took over in 1833, the mission slowly fell apart. After California became a U.S. state in 1850, many tried to restore it. But most efforts failed until O'Sullivan arrived in 1910. Restoration work continues today, and "Father Serra's Church" is still used for religious services.

More than 500,000 people visit the mission each year, including 80,000 school children. The ruins of "The Great Stone Church" are famous. This church was mostly destroyed by an earthquake in 1812. The mission is also well-known for the annual "Return of the Swallows" on March 19. Many artists, writers, and filmmakers have featured Mission San Juan Capistrano in their work.

In 1984, a new church was built nearby, called Mission Basilica San Juan Capistrano. Today, the mission compound is a museum. The Serra Chapel inside the mission still serves as a church for the local community.

The Mission's Story

The First People Here

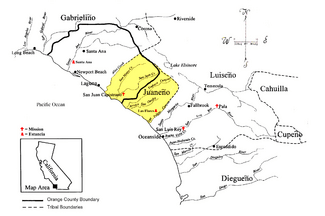

The area where the mission stands was home to the Juaneño Native American people. They are also known as the Acjachemen. Their language was similar to the Luiseño language spoken by a nearby tribe.

The Acjachemen lived in an area stretching from northern San Diego County to the Orange County coast. They had villages along the San Juan Creek and San Mateo Creek. The mission was built in an area with many villages along the lower San Juan Creek. The Acjachemen lived in permanent villages and seasonal camps. Villages could have from 35 to 300 people.

Each group had its own land and was independent. They connected with other villages through trade and shared beliefs. Their society had three classes: leaders, successful families, and others. Village leaders, called Nota, led ceremonies with a council of elders. These leaders made decisions for the community.

We know a lot about these native people from early explorers. Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo wrote about coastal villages in 1542. Fray Gerónimo Boscana, a Franciscan priest at San Juan Capistrano, wrote a detailed study of their religious practices. Their religion, called Chinigchinich, gave village chiefs religious power.

Spanish Mission Life (1776–1833)

Juan Crespí, an explorer in 1769, wrote the first account of Europeans meeting the native people here. His group camped near the future mission site on July 23.

In 1775, the Spanish decided to build a mission between Mission San Diego de Alcalá and Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. The spot was already known as "San Juan Capistrano."

Up from the south slow filed a train,

Priests and Soldiers of Old Spain,

Who, through sunlit lomas wound

With cross and lance, intent to found

A mission in the wild to John

Soldier-Saint of Capistrano.

At this spot, about 26 Spanish Leagues north of San Diego, a simple shelter was built. Two bronze bells were hung from a tree branch, and a wooden cross was put up. Fermín Lasuén officially started the mission on October 30, 1775. It was near a native village called "Sajavit," so it was named La Misión de San Juan Capistrano de Sajavit.

Eight days later, Father Gregório Amúrrio arrived with supplies. But bad news came from San Diego: natives had attacked that mission and killed a missionary. Fearing more attacks, the priests quickly buried the San Juan Capistrano Mission bells. Soldiers and priests then fled to San Diego for safety.

One year later, Junípero Serra returned with Amúrrio and Pablo de Mugártegui. They arrived on October 30 or 31, 1776. They dug up the bells and found the original wooden cross still standing. Serra held a special Mass on November 1, 1776, which is now the official founding date. Because of water problems, the mission moved about three miles west. The new spot was near two streams, the Trabuco and San Juan.

Mission San Gabriel helped by sending cattle and native workers. Amúrrio performed the first baptism on December 19, 1776. The first marriage was on January 23, 1777. The mission's records of baptisms, marriages, and burials are still kept today. Serra visited again in October 1777 and confirmed 213 people in 1783.

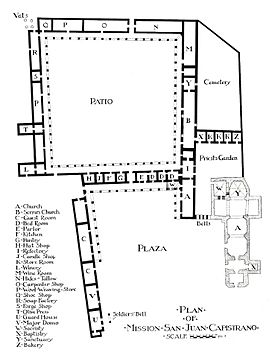

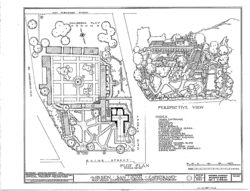

In 1778, a small adobe chapel was blessed. It was replaced by a larger, 115-foot-long church in 1782. This church, called "Serra Chapel," is the oldest standing building in California. It is also the only church where Serra is known to have led services. By the time the chapel was finished, other buildings like living quarters, kitchens, workshops, and barracks were also built.

California's first vineyard was at the mission, planted in 1779. The "Mission" grape was used to make the first wine in Alta California in 1783. They made red and white wines, brandy, and a sweet wine called Angelica. In 1791, the mission's original bells were moved to a permanent bell mounting. The mission grew, and by 1794, over seventy adobe homes were built for the Mission Indians. These homes are some of the oldest residential buildings in California.

Building the Great Stone Church

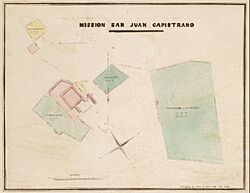

Because the mission was growing, a larger, European-style church was needed. Priests hired Isídro Aguilár, a master stonemason, from Culiacán. Aguilár designed a unique church with a domed stone roof, unlike the usual flat wooden roofs. His design included six vaulted domes.

Work on "The Great Stone Church" began on February 2, 1797. It was the only mission church in Alta California not made of adobe. It was shaped like a cross, 180 feet long and 40 feet wide, with 50-foot-high walls. It also had a 120-foot-tall bell tower next to the entrance. People say the tower could be seen for 10 miles and the bells heard even farther.

The building was made of sandstone on a seven-foot-thick foundation. All the native workers helped with construction. Stones were brought from miles away by carts, by hand, or dragged. Limestone was crushed to make a strong mortar.

On November 22, 1800, an earthquake cracked the walls, requiring repairs. Sadly, Aguilár died six years into the project. The priests and workers continued his work, but without a master mason, the walls became uneven. A seventh roof dome had to be added. The church was finally finished in 1806 and blessed on September 7. It was the most magnificent church in California.

The Great Stone Church Falls

On December 8, 1812, a powerful earthquake hit Southern California during Sunday service. The doors of the church were jammed shut. When the shaking stopped, most of the main part of the church had collapsed. The bell tower was destroyed. Forty native worshipers and two boys ringing the bells died under the rubble. They were buried in the mission cemetery.

This was a big disaster for the mission. Services immediately moved back to Serra's Church. A year later, a brick bell wall was built to hold the four bells saved from the stone church's ruins. Since the back part of the stone church was still standing, people tried to rebuild it in 1815. But they lacked the skills, so it failed. After this, all new buildings at the mission were simple and practical. In 1814, a small hospital was built for the sick.

Pirates Attack the Mission

On December 14, 1818, a French privateer named Hipólito Bouchard sailed his ships near the mission. Bouchard, known as "California's only pirate," had recently attacked other towns. Comandante Ruíz sent 30 soldiers to protect the mission.

Bouchard's men demanded supplies, but the soldiers refused. Bouchard then ordered an attack, sending 140 men and cannons. The mission guards fought but were outnumbered. The pirates looted the mission warehouses and caused minor damage. They also reportedly set fire to some straw houses. Reinforcements arrived the next day, but the ships had already left.

Even though the mission was damaged, all ammunition, supplies, and valuables were taken. This event is now a colorful part of the mission's history. An annual celebration remembers "The Day that Pirates Sacked the Mission."

Mexico Takes Over

Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821. The mission slowly declined in the 1820s and 1830s. Diseases reduced the cattle herds, and weeds made farming difficult. Floods and droughts also caused problems. Spanish settlers wanted the mission's fertile lands, which was a big threat.

Many native people left the mission, and without regular care, the buildings fell apart faster. In 1823, the Las Flores Asistencia was built as a rest stop for traveling priests. Around 1820, a cattle ranch was set up near the Santa Ana River. The adobe building for the ranch manager and cowboys is now called the Diego Sepúlveda Adobe.

In 1826, Governor José María de Echeandía announced that some native people could be freed from mission rule. He wanted to try this plan at Mission San Juan Capistrano. The Mexican government later ordered all Spaniards under 60 to leave Mexican lands. However, Governor Echeandía helped Father Barona stay at the mission.

Even before Mexico's independence, the mission was struggling. In 1833, the Mexican Congress passed a law to take over the missions. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to be affected in 1834.

Rancho Days (1834–1849)

On November 22, 1834, the mission's property was officially taken over. An inventory listed all the mission's assets, including buildings, chapel, tools, ranch lands, and library. The total value was $54,456. The mission had 8,000 cattle, 4,000 sheep, and other animals and crops.

After this, the Franciscan priests mostly left the mission. Local people took building materials from the mission. By 1835, little was left of the mission's wealth. The mission was called "in a ruinous state" in 1841. Governor Juan B. Alvarado made San Juan Capistrano a secular Mexican town. The few people still living there were given land. The area around the mission quickly decayed.

In 1845, the mission property was sold for $710 worth of tallow and hides. It was bought by John (Don Juan) Forster, the governor's brother-in-law. His family lived in the friars' quarters for the next twenty years. Other families also moved into parts of the mission buildings. The last resident missionary, Vicente Pascual Oliva, died in 1848.

California Becomes a State (1850–1900)

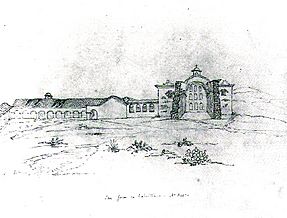

In the 1850s, artists began drawing the mission ruins. The oldest drawing, from 1850, shows that parts of the stone church's domes survived the 1812 earthquake. The first known photograph of the mission was taken in 1860. The ruins were often compared to ancient Greek and Roman sites.

In 1860, an attempt to restore the stone church caused more damage. This led to the collapse of the domes over the transept and sanctuary.

A smallpox outbreak in 1862 nearly wiped out the remaining Juaneño Indians. On March 18, 1865, President Lincoln returned ownership of the mission to the Catholic Church. The mission's pastor from 1866 to 1886 was José Mut. He made some changes but did little to stop the mission from falling apart further. By 1873, about forty Juaneño were still connected to the mission. Many Juaneño moved away between 1880 and 1900 as new towns grew.

In the 1880s, many articles and books about the missions appeared. By 1891, the roof of Serra Chapel collapsed, and it had to be abandoned. The original adobe church was changed to be used as a parish church. In 1894, a new train station was built nearby in the "Mission Revival Style." It is believed that stones and tiles from the decaying mission buildings were used for the station.

The "Landmarks Club of Southern California," led by Charles Fletcher Lummis, began the first real restoration efforts in 1895. They cleared away debris, patched walls, and put new roofs on some buildings.

Modern Times and Restoration (Since 1901)

After Mut left in 1886, the mission had no permanent pastor and continued to decline. St. John O'Sullivan arrived in San Juan Capistrano in 1910. He was recovering from a stroke and illness. He became very interested in the mission and started rebuilding it piece by piece.

O'Sullivan first repaired the roof of the Serra Chapel, which was being used as a storage room. He used sycamore logs, just like the original roof. He also added a window to bring in natural light. Other repairs were made as money allowed. An architect named Arthur B. Benton strengthened the chapel walls.

The most striking part of the chapel is its "Golden Altar" (retablo). This beautiful Baroque artwork is made of 396 pieces of cherry wood covered in gold leaf. It is about 400 years old and came from Barcelona. It was installed between 1922 and 1924.

Many Hollywood movies have used San Juan Capistrano as a setting. D.W. Griffith's 1910 western film The Two Brothers was the first film shot in Orange County. On January 7, 1911, silent film star Mary Pickford secretly married actor Owen Moore in the mission chapel. Artist Charles Percy Austin painted a picture of their wedding.

Flooding damaged part of the mission's front in 1915. Heavy storms in 1916 washed away part of the barracks building, which O'Sullivan rebuilt. In 1916, a ten-cent admission fee was charged to help pay for preservation. In 1918, the mission became a parish, with O'Sullivan as its first modern pastor. An earthquake in 1918 caused some damage. In 1919, author Johnston McCulley created the character "Zorro" and set his first story, The Curse of Capistrano, at the mission.

In 1920, the "Sacred Garden" was created. The full restoration of the Serra Chapel was finished in 1925. O'Sullivan died in 1933 and was buried in the mission cemetery. His tomb is at the foot of a Celtic cross he put up to honor the mission's builders.

After O'Sullivan, Arthur J. Hutchinson continued the preservation work. He made important archaeological discoveries. Later pastors, Vincent Lloyd-Russell and Paul M. Martin, also continued the efforts. In 1937, the U.S. National Park Service surveyed and photographed the mission. This work helped with future excavations and rebuilding. Monsignor Martin led a big preservation effort after the 1987 Whittier Narrows earthquake.

In 2002, the "Great Stone Church" was listed among the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund. The latest earthquake safety upgrades were finished in 2004, costing $7.5 million.

Many events are held at the mission today. The "Battle of the Mariachis" is a main fundraising event. It started in 2004 to celebrate the mission's heritage.

Special Recognitions

- California Historical Landmark #227 – Diego Sepúlveda Adobe Estancia

- ASM International Historical Landmark (1988) – "Metalworking Furnaces"

- World Monuments Fund List of 100 Most Endangered Sites (2002); "The Great Stone Church"

- Orange County Historic Civil Engineering Landmark (1992)

How the Mission Worked

Missions aimed to be self-sufficient. Farming was the most important activity. Barley, maize, and wheat were the main crops. Hundreds of cattle, horses, mules, sheep, and goats were raised. In 1790, the mission had 7,000 sheep and goats, 2,500 cattle, and 200 mules and horses.

Olives were grown, cured, and pressed to make oil for the mission and for trade. Grapes were also grown and made into wine for religious use and trade. The "Mission grape" was first planted in 1779. In 1783, the first wine in Alta California came from this mission.

Grains were ground into flour. The mission's kitchens and bakeries prepared thousands of meals daily. Candles, soap, and ointments were made from animal fat in large vats. There were also vats for dyeing wool and tanning leather, and looms for weaving. Large warehouses stored food and materials.

Three long aqueducts brought water to the central courtyard. The water was collected in large cisterns, filtered for drinking and cooking, or used for cleaning. The mission also made its own building materials. Carpenters shaped beams and doors. Bricks and roof tiles were fired in ovens to make them stronger. Ceramic pots and dishes were also made in the kilns.

Before the missions, native people used bone, shells, stone, and wood for tools and building. The missionaries taught them farming, crafts, and livestock care. The native workers produced everything needed at the missions. After 1811, they even supported the government of California. The mission's foundry was the first to introduce the native people to ironworking. Blacksmiths used the mission's Catalan furnaces to make iron tools, hardware, crosses, and even cannons. Iron was acquired through trade, as the mission could not mine or process metal ores.

The Mission Bells

Bells were very important for daily life at the mission. They rang for mealtimes, work, religious services, births, and funerals. They also signaled when a ship or missionary was arriving. The original bells hung from a tree for about fifteen years until a bell tower was built in 1791. What happened to those first bells is unknown.

New bells were made in Chile for "The Great Stone Church." All four of Mission San Juan Capistrano's bells have names and inscriptions:

- "Praised by Jesus, San Vicente. In honor of the Reverend Fathers, Ministers (of the Mission) Fray Vicente Fustér, and Fray Juan Santiago, 1796."

- "Hail Mary most pure. Ruelas made me, and I am called San Juan, 1796."

- "Hail Mary most pure, San Antonio, 1804."

- "Hail Mary most pure, San Rafael, 1804."

After the 1812 earthquake, the two largest bells cracked. They no longer made clear sounds. Still, they were hung in the new bell wall built the next year. During the mission's busiest time, another bell hung at the west end of the front corridor.

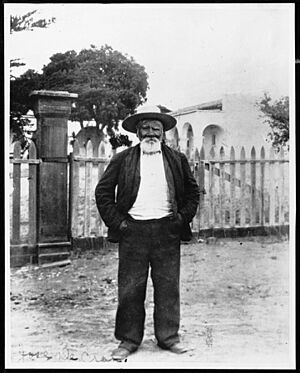

José de Gracia Cruz, known as Acú, was a descendant of the Juaneño Indians. He was the mission's bell ringer until he died in 1924. He shared many stories and legends about the mission.

On March 22, 1969, President Richard M. Nixon and Pat Nixon visited the mission and rang the Bell of San Rafael. A bronze plaque on the bell wall remembers this event. In 2000, the new Mission Church became a minor basilica. Exact copies of the damaged bells were made in the Netherlands. These new bells were placed in the bell wall, and the old ones are now on display.

Fun Stories and Legends

Local Legends

The fall of "The Great Stone Church" led to a sad legend about a young native girl named Magdalena. She was killed in the collapse. Magdalena loved an artist named Teófilo, but they were too young to marry. On that terrible December morning, Magdalena was walking into the church when the earthquake hit. Teófilo rushed in to save her but could not. When the rubble was cleared, they were found together, holding each other. People say that on moonlit nights, you can sometimes see a young girl's face in the ruins, lit by candlelight.

Other legends include a faceless monk who walked the mission corridors. There is also a headless soldier who guarded the front entrance.

The Famous Swallows Return

American cliff swallows are birds that fly all the way from Goya, Argentina, to the warmer American Southwest each spring. According to legend, these birds have visited San Juan Capistrano for centuries. They first took shelter at the mission when an angry innkeeper destroyed their nests. The mission's location near two rivers was perfect for the swallows. It provided plenty of insects to eat, and the young birds were safe inside the old church ruins.

An article in 1915 noted the birds' habit of nesting under the mission's eaves. This made the swallows the mission's "signature icon." Father O'Sullivan used this interest to help raise money for restoration. Bell ringer Acú used to tell a colorful tale that the swallows flew over the Atlantic Ocean to Jerusalem each winter. They carried small twigs to rest on the water during their journey.

On March 13, 1939, a popular radio show broadcast live from the mission, announcing the swallows' arrival. Composer Leon René was inspired and wrote the song "When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano." This song became very popular. Many musicians have recorded it. A room at the mission is dedicated to René, displaying his piano and other items.

Each year, the Fiesta de las Golondrinas (Festival of the Swallows) is held in San Juan Capistrano. It is a week-long celebration that ends with the Swallows Day Parade. Tradition says the main group of swallows arrives on March 19 (Saint Joseph's Day) and flies south on October 23 (Saint John's Day).

When the swallows come back to Capistrano

That's the day you promised to come back to me

When you whispered, "Farewell," in Capistrano

'twas the day the swallows flew out to sea

In recent years, fewer swallows have returned to the mission. This is thought to be because of more buildings in the area. This gives them more places to nest and fewer insects to eat.

The Giant Pepper Tree

The largest California pepper tree in the United States used to be at Mission San Juan Capistrano. It was 57 feet tall and planted in the 1870s. Sadly, it was cut down in 2005 due to disease. This type of tree was common in early California. The oldest pepper tree in California is at Mission San Luis Rey de Francia.

Images for kids

-

Statue of Junípero Serra at the Mission.

-

An 1894 painting by Frederick Behre.

-

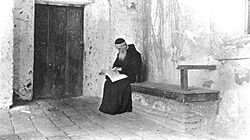

Clerical historian Zephyrin Engelhardt visited the mission many times.

See also

In Spanish: Misión San Juan Capistrano para niños

In Spanish: Misión San Juan Capistrano para niños

- Spanish missions in California

- List of Spanish missions in California

- Diego Sepúlveda Adobe

- Las Flores Estancia

- San Juan Hot Springs

- Oldest churches in the United States

- List of the oldest buildings in the United States

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |