Confirmation facts for kids

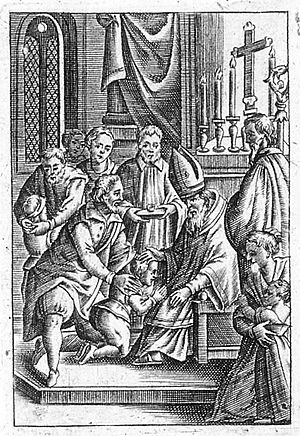

Confirmation is a special religious ceremony in many Christian churches. It's often seen as a way to strengthen the connection made during infant baptism. People who are confirmed are called confirmands. For adults, it's a chance to publicly say they believe in their faith. This ceremony often involves a laying on of hands by a religious leader.

In Catholicism, confirmation is considered a sacrament, which is a holy ritual. In Eastern Christianity, it's called chrismation and usually happens right after baptism, even for babies. In Western Christianity, confirmation usually takes place when a child is old enough to understand it, often in their early teenage years. If an adult gets baptized, confirmation usually happens at the same time. For some Christians, especially teenagers, confirmation can also feel like a "coming of age" moment, marking a step into adulthood within their faith.

Many Protestant churches, like Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, and Reformed churches, see confirmation as a special rite. During this rite, a person who has already been baptized makes a profession of faith. For Lutherans, Anglicans, and other traditional Protestant groups, confirmation is often needed to become a full member of the church. In Catholic teaching, baptism makes you a member, but confirmation "completes" the grace received in baptism. Both Catholic and Methodist churches teach that confirmation helps the Holy Spirit strengthen a baptized person for their faith journey.

Some Christian groups, like Baptists and Anabaptists, do not practice infant baptism, so they don't have confirmation. Instead, they focus on "believer's baptism" when a person is old enough to choose their faith.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) doesn't baptize infants. People can be baptized after they reach the "age of accountability." Confirmation in the LDS Church happens soon after baptism. It's seen as very important for baptism to be complete.

There's also a similar ceremony called confirmation in Reform Judaism.

Contents

What are the roots of Confirmation?

The idea of confirmation comes from the early Christian Church, as described in the New Testament. In the Gospel of John, Jesus talks about the Holy Spirit coming to his apostles. Later, after Jesus came back to life, he breathed on them, and they received the Holy Spirit (John 20:22). This was fully completed on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1–4). This outpouring of the Spirit was a sign of a new age, as predicted by prophets.

After Pentecost, the New Testament shows that the apostles gave the Holy Spirit to others by laying on of hands.

- In the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 8:14–17), it says that Deacon Philip baptized people, but only the apostles could give the Holy Spirit through laying on of hands.

- The Bible says: "Now when the apostles in Jerusalem heard that Samaria had accepted the word of God, they sent them Peter and John, who went down and prayed for them, that they might receive the holy Spirit, for it had not yet fallen upon any of them; they had only been baptized in the name of the Lord Jesus. Then they laid hands on them and they received the holy Spirit."

- Later, in Acts 19, it clearly states that Apostle Paul laid his hands on newly baptized people, and they received the Holy Spirit.

How do different Christian churches view Confirmation?

Catholic Church

In the Catholic Church, confirmation (also called chrismation) is one of the seven sacraments. These sacraments were started by Christ to give special grace and strengthen a person's bond with God.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains that confirmation gives a special outpouring of the Holy Spirit, just like the apostles received on Pentecost. This sacrament:

- Connects us more deeply to God as our Father.

- Unites us more strongly with Christ.

- Increases the gifts of the Holy Spirit within us.

- Makes our connection with the Church more complete.

- Gives us special strength from the Holy Spirit to share and defend our faith. It helps us be true witnesses of Christ, speak boldly about Him, and never be ashamed of the Cross.

In the Western Catholic Church, confirmation is usually given to people old enough to understand it. The main person who gives confirmation is a bishop. However, if needed, a bishop can allow certain priests to give the sacrament. When an adult is baptized, they usually receive confirmation right away.

In Eastern Catholic Churches, the local priest usually gives this sacrament. They use special olive oil called chrism that has been blessed by a bishop. This happens right after baptism, which is often for infants. This practice is very similar to how it was done in the early Church.

Confirmation in the West: A brief history

In the Western Church, confirmation was separated from baptism over time. This was done so that the bishop could personally confirm each person. In the early Church, the bishop would perform all three sacraments of initiation: baptism, confirmation, and Eucharist. As more infants were baptized, the chrismation (confirmation) was delayed until the bishop could be there.

Over centuries, the age for confirmation and Communion changed. In the 18th century, some places started giving First Communion before confirmation. Later, in 1910, Pope Pius X lowered the age for First Communion to about seven years old. This led to the common practice today where children often receive First Communion in elementary school and confirmation later, in middle or high school.

The Catholic Church teaches that confirmation makes a person "a soldier of Christ." This means they are strengthened to spread and defend their faith.

Eastern Churches

Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic churches call this sacrament "chrismation." They connect it very closely with baptism, giving it immediately after baptism, even to babies.

The tradition in the Orthodox Church says that the apostles started using chrism (holy oil) instead of laying on hands as the number of new Christians grew. The apostles would bless a vessel of oil, and this oil would then be used by priests to give the Holy Spirit to the newly baptized. This same chrism is still used today, with new chrism added as needed. It's believed that today's chrism contains some of the original oil blessed by the apostles.

When people from other Christian churches become Orthodox, they are often received through chrismation without being re-baptized. However, this can depend on the local bishop.

The Orthodox chrismation ceremony happens right after baptism. The priest makes the sign of the cross with chrism on different parts of the person's body (forehead, eyes, nose, lips, ears, chest, hands, and feet). With each anointing, the priest says: "The seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit. Amen." Then, the priest leads the newly baptized and their sponsors in a procession around the Gospel Book.

Eastern Churches perform chrismation right after baptism so that the newly baptized person, even an infant, can receive Holy Communion.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) uses the term "ordinance" for confirmation. They believe that confirmation is a "baptism by fire" where the Holy Spirit enters a person. This cleanses them from the effects of past sins and welcomes them into the church as a new person in Christ. Through confirmation, a person receives the Gift of the Holy Ghost, which means the Holy Ghost can be with them always, as long as they live righteously.

The ceremony is simpler than in Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches. An ordained clergyman performs it by:

- Laying hands on the person's head and saying their full name.

- Stating that the ordinance is done by the authority of the Melchizedek Priesthood.

- Confirming the person as a member of the LDS Church.

- Giving the gift of the Holy Ghost by saying, "Receive the Holy Ghost."

- Giving a special priesthood blessing.

- Closing in the name of Jesus Christ.

Lutheran Churches

In Lutheran churches, confirmation is a public declaration of faith. It's prepared for through careful teaching. It's often called "affirmation of baptism" because it's a mature and public statement of the faith that completes the church's confirmation program. Lutherans don't consider confirmation a "sacrament of the Gospel" like Baptism or Eucharist. It often happens on special Sundays like Palm Sunday or Pentecost.

Anglican Communion

In the Anglican Communion, confirmation is listed as one of the rites "commonly called Sacraments" but not a "Sacrament of the Gospel" (like baptism and the Holy Eucharist). This means it's a holy rite, but not directly started by Christ in the same way as baptism. Many Anglicans, especially Anglo-Catholics, do count it as one of seven sacraments.

The Anglican confirmation service includes renewing baptismal vows. This has led some to see confirmation as a renewal of promises made at baptism. However, the main Anglican view is that it's a strengthening by the Holy Spirit.

Methodist Churches

In the Methodist Church, confirmation is also seen as one of the "five lesser sacraments." The Methodist Worship Book says that in confirmation, baptized people declare their faith in Christ and are strengthened by the Holy Spirit. It reminds them they are baptized and that God is still working in their lives. They respond by saying they belong to Christ and the Church. At a confirmation service, baptized Christians also become members of the Methodist Church.

For those baptized as infants, confirmation often happens when they are in middle school (around 6th to 8th grade), but it can be earlier or later. Candidates for confirmation take classes to learn about Christian beliefs, Methodist history, and the Bible.

United Protestant Churches

In United Protestant Churches, like the United Church of Canada, confirmation is a rite where a Christian person takes on the responsibilities of the promises made at baptism.

What is a Confirmation name?

In some parts of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism, people being confirmed might choose a new name. This is usually the name of a biblical character or a saint. This gives them an extra patron saint as a protector. This practice is not always mentioned in official church books and is not common everywhere.

Historically, baptism and giving a personal name were linked. At confirmation, which is similar to baptism in some ways, it became common to take a new name. For example, King Henry III of France was baptized Edouard Alexandre but received the name Henri at confirmation. Today, the confirmation name is usually not used much, though some treat it as an extra middle name.

Can Confirmation be repeated?

The Catholic Church believes that confirmation, like baptism, leaves a permanent mark on a person's soul. So, it cannot be received twice. If someone was confirmed in an Eastern Orthodox Church (which the Catholic Church sees as having valid sacraments) and later joins the Catholic Church, they are not re-confirmed. However, if someone was confirmed in a Protestant church, the Catholic Church would confirm them (for the first and only time, in their view) because they believe Protestant churches do not have properly ordained ministers to give the sacrament.

In Lutheran Churches, people baptized in other Christian churches are confirmed as Lutherans after a period of teaching.

In the Anglican Communion, if a person was confirmed in another Christian group by a bishop or priest whose ordination is recognized as valid, they are "received" into the Anglican Church rather than re-confirmed.

Eastern Orthodox churches sometimes "re-Chrismate" converts or people who return to the Orthodox Church after leaving. They believe that the new Chrismation is the only valid one, or that it's part of a process of welcoming someone back into the Church.

Are there similar ceremonies in other religions?

Judaism

In the 1800s, Reform Judaism created a ceremony called confirmation, which was loosely based on Christian confirmation. At that time, some Reform Jews felt that bar/bat mitzvah (which happens around age 13) was too young for children to fully understand what it means to be religious. So, confirmation was developed as a later ceremony.

Today, many Reform Jewish congregations have confirmation ceremonies to mark the biblical festival of Shavuot. It's a time for young adults to commit to Jewish study and reaffirm their connection to the Covenant (the special agreement between God and the Jewish people). Confirmation usually happens in tenth grade after a year of study.

Confirmation was first officially mentioned in Jewish texts in 1810 in Westphalia. At first, only boys were confirmed, often at home. But soon, Jewish girls were also confirmed, and the ceremony moved to the synagogue. It became common to hold confirmation during the festival of Shavuot. This was seen as fitting because Shavuot celebrates when the Israelites accepted God's Law at Mount Sinai. So, each new generation could follow this example and declare their willingness to be faithful.

Secular confirmations

Some non-religious groups, especially Humanist ones, have "civil confirmations" for older children. These ceremonies are a way for young people to state their beliefs about life, offering an alternative to traditional religious ceremonies.

In some countries that were officially atheist, like the former German Democratic Republic (East Germany), non-religious ceremonies were encouraged to replace Christian ones. For example, the Jugendweihe (youth dedication) became popular. This ceremony, which started in 1852, was a solemn event marking the transition from youth to adulthood, created as an alternative to Christian confirmation.

See also

In Spanish: Confirmación para niños

In Spanish: Confirmación para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |