Georgian Orthodox Church facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia |

|

|---|---|

| საქართველოს სამოციქულო ავტოკეფალური მართლმადიდებელი ეკლესია | |

Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi

|

|

| Type | Autocephaly |

| Classification | Christian |

| Orientation | Eastern Orthodox |

| Scripture | |

| Theology | Eastern Orthodox theology |

| Polity | Episcopal polity |

| Catholicos-Patriarch | Ilia II of Georgia |

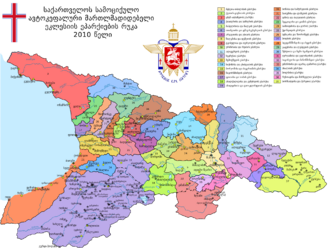

| Eparchies | 50 |

| Language | Georgian |

| Headquarters | Tbilisi, Georgia |

| Territory | Georgia |

| Possessions | Western Europe, Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Jordan, Australia, North America |

| Founder | Saint Andrew (Colchis); Saint Nino, Mirian III (Iberia) |

| Independence | From Antioch dates vary between 467 CE—491 CE and 1010 From Russia in 1917 and 1943 |

| Recognition | Autocephaly gradually conferred by the Church of Antioch and recognized by most of the Church, dates vary between 467-491 and 1010. Autocephaly quashed by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1811 on orders of the Tsar, partially restored in 1917, fully restored in 1943. Recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1990. |

| Separations | Abkhazian Orthodox Church (2009) |

| Members | 3.5 million (2011) |

The Georgian Orthodox Church is a very old Christian church in the country of Georgia. It is part of the larger Eastern Orthodox family of churches. This means it shares the same beliefs and traditions with other Orthodox churches around the world.

Most people in Georgia are members of this church. It is one of the oldest churches globally. The church believes it was started by Saint Andrew in the 1st century AD. Later, Saint Nino helped spread Christianity in Georgia in the 4th century AD. The church is led by a group of bishops called the Holy Synod. The main leader is called the Patriarch of All Georgia, who is currently Ilia II. He was chosen in 1977.

For most of Georgia's history, Eastern Orthodox Christianity was the official religion. This changed in 1921 when Georgia became part of the Soviet Union. The current Constitution of Georgia says the church has a special role in the country's history. However, it also states that the church and the government are separate. A special agreement from 2002 helps define how they work together.

The Georgian Orthodox Church is very trusted in Georgia. A survey in 2013 showed that 95% of people had a good opinion of it. It is seen as a very important organization in the country.

Contents

- History of the Georgian Orthodox Church

- How the Church is Organized

- Images for kids

- See also

History of the Georgian Orthodox Church

How Christianity Began in Georgia

Early Stories of Christianity in Georgia

The Georgian Orthodox Church has stories about how Christianity first came to Georgia. They believe that Saint Andrew, one of Jesus's first followers, was the first to preach the Christian message there. The church says Andrew traveled all over Georgia, bringing a special icon (a religious image) of the Virgin Mary. He is said to have started the first Christian groups, which are seen as the ancestors of the church today.

However, many historians think these stories are more like legends. They believe these tales came from later Byzantine stories about Saint Andrew's travels. Other apostles, like Simon the Canaanite and Saint Matthias, are also said to have preached in Georgia.

Georgia Becomes Christian

We don't know much about how Christianity spread in Georgia before the 4th century. The first clear event was the work of Saint Nino. She is honored as "Equal to the Apostles" because of her important role. Tradition says she was a Roman general's daughter from Cappadocia. She preached in the ancient Georgian kingdom of Iberia (now eastern Georgia) in the early 300s.

Her efforts led to King Mirian III, his wife Queen Nana, and their family becoming Christian. Historians believe King Mirian converted around 334 AD and made Christianity the official religion of Iberia around 337 AD. Before this, people in Georgia practiced other religions like Mithras worship, pagan beliefs, and Zoroastrianism. After Christianity became official, these older religions slowly faded away.

Priests from Constantinople helped the king and organized the church. Christianity spread quickly in the flat areas, but older beliefs lasted longer in the mountains. Western Georgia, known as Lazica, was more connected to the Roman Empire. Some of its cities already had bishops by 325 AD.

Growth and Changes of the Church

The conversion of Iberia was just the start for the Georgian Orthodox Church. Over the next few centuries, the church changed a lot. By the 11th century, it had most of the features it still has today. These changes included how independent the church was, how it became a national church for all of Georgia, and how its beliefs developed.

Becoming an Independent Church

In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Church of Iberia was closely connected to the Church of Antioch. All its bishops were chosen in Antioch. Around 480 AD, the Byzantine government recognized the leader of the Georgian church as a "catholicos." This was a step towards more independence.

The church still had some ties to Antioch. The Catholicos could choose local bishops, but his own election needed to be approved by Antioch until the 740s. Even after that, payments were sent to the Antiochian Church. This changed after the 11th century. The Catholicos of Mtskheta (a city in Georgia) gained power over all of western Georgia. From then on, the head of the Georgian Church was called the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia. The church became fully independent in its own matters and in its dealings with other churches. This was true except for a period between 1811 and 1917. Melchisedek I (1010–1033) was the first Catholicos-Patriarch of all Georgia.

Other sources give different dates for when the church became fully independent. Some say 467 AD, others 484 AD. The Encyclopedia Britannica suggests it was likely granted by the Byzantine emperor Zeno (474–491 AD).

Expanding Across Georgia

When the church first started, Georgia was not a single country. It only became united in the early 11th century. Western Georgia was more influenced by the Byzantine Empire. Eastern Georgia had influences from Byzantine, Armenian, and Persian cultures. This difference affected how Christianity grew in each area.

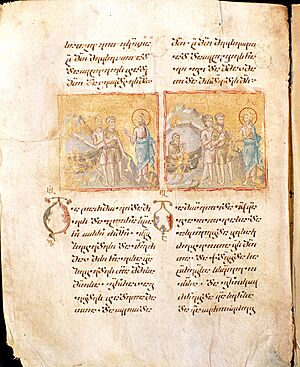

In the east, the church grew under the protection of the kings of Iberia. A big step for the church was the creation of the Georgian alphabet. This new writing system helped spread Christianity to the local people. Monasteries also grew a lot in Iberia in the 6th century. They helped bring in new ideas and encouraged local writers. People started writing religious books in Georgian, like stories about saints. Many early saints were not Georgian, showing the church was not yet strictly national.

This changed in the 7th century after the Muslim conquests. This new threat made the church focus more on its own people. It became a "Kartvelian Church." Bishops and the Catholicos were now all ethnic Georgians. The saints written about from this time were also Georgian.

In western Georgia, churches were under the control of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Their language was Greek. Over time, as Byzantine power weakened, the western churches joined the eastern ones. By the end of the 9th century, the western church recognized the Catholicos of Mtskheta. When Georgia became a united kingdom in the late 10th century, the Georgian Church also became unified.

Connections with Armenian and Byzantine Churches

In the early centuries of Christianity, the South Caucasus region was more connected culturally. The Armenian Church started earlier and was very influential. It had a strong impact on the early beliefs of the Georgian church. The Church of Jerusalem also influenced Georgian church services.

After the Council of Chalcedon in 451 AD, there were disagreements about Christian beliefs. The Armenian Church and some parts of the Church of Antioch did not accept the council's decisions. At first, the Georgian church leaders sided with the Armenians. However, there were always different opinions among the clergy. King Vakhtang Gorgasali of Iberia wanted to ally with Byzantium. He accepted a compromise from the Byzantine Emperor in 482 AD.

Around 600 AD, tensions grew between the Armenian and Georgian churches. The Armenian Church tried to become more important in the Caucasus. But the Georgian Catholicos, Kirion I, leaned towards the Byzantine side. This was because Iberia was looking for Byzantine support against the Persian Empire. In 607 AD, the Georgian Church officially separated from the Armenian Church.

In the centuries that followed, the Georgian Church became more aligned with the Byzantine (Eastern Orthodox) tradition. Differences in beliefs remained. The joining of western and eastern Georgian churches from the 9th century also confirmed the Georgian Church's Orthodox nature. Byzantine church practices and culture spread throughout Georgia.

The Church During Georgia's Golden Age

Between the 11th and early 13th centuries, Georgia had a "Golden Age." This was a time of great political, economic, and cultural growth. The Bagrationi dynasty united western and eastern Georgia into one kingdom. To do this, the kings relied heavily on the church's influence. They gave the church many economic benefits and tax exemptions.

At the same time, kings like David the Builder (1089–1125) used their power to get involved in church matters. In 1103, he called a church meeting that strongly rejected Armenian beliefs. He also gave a lot of power to his friend and advisor, George of Chqondidi, second only to the Patriarch. For centuries, the church remained a very powerful institution. Its economic and political power was often equal to that of the most important noble families.

Christianity's Cultural Impact in Medieval Georgia

During the Middle Ages, Christianity was at the heart of Georgian culture. The Georgian alphabet was created to help spread the Christian message, which led to a rich written culture. Monasticism (monks living in communities) played a huge role. It began in Georgia in the 6th century when monks from Assyria founded monasteries, like David Gareja. Georgian monks soon joined them, creating important religious writings.

The "golden age" of Georgian monasticism was from the 9th to the 11th century. During this time, Georgian monasteries were built outside the country, including on Mount Sinai and Mount Athos. Gregory of Khandzta (759–861) was a very important figure in Georgian monasticism. He founded many communities.

Special art forms developed in Georgia for religious purposes. These included calligraphy (beautiful writing), polyphonic church singing (music with many voices), and cloisonné enamel icons, like the Khakhuli triptych. The "Georgian cross-dome style" of architecture was also developed for churches. Famous examples include the Gelati Monastery and Bagrati Cathedral in Kutaisi, and the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta.

Important Georgian Christian thinkers and artists included Peter the Iberian (5th century) and George of Athos (1009–1065). Philosophy also thrived, especially at the Gelati Monastery Academy.

The Church Under Russian and Soviet Rule

In 1801, the Russian Empire took over eastern Georgia. On July 18, 1811, the Russian authorities ended the Georgian Church's independent status. This happened despite strong opposition from Georgians. The Georgian Church became part of the Russian Orthodox Church. From 1817, the main bishop in charge was Russian. He often did not know the Georgian language or culture. Georgian church services were replaced with Church Slavonic (an old Russian church language). Old paintings in churches were covered up. Publishing religious books in Georgian was heavily controlled. People started asking for the church's independence again in the 1870s.

After the Russian Tsar was overthrown in March 1917, Georgia's bishops brought back the Georgian Orthodox Church's independence on March 25, 1917. The Russian Orthodox Church did not accept this at first. After the Red Army invasion of Georgia in 1921, the Georgian Orthodox Church faced harsh treatment. The government, which did not believe in religion, closed hundreds of churches. Many monks were killed during Joseph Stalin's purges.

The Russian Orthodox Church finally recognized the Georgian Orthodox Church's independence on October 31, 1943. This was ordered by Stalin as part of a more tolerant policy towards Christianity during World War II. However, new campaigns against religion happened after the war. The church also faced problems with corruption.

Signs of revival appeared in the 1970s. Eduard Shevardnadze, a Georgian Communist Party leader, became more tolerant. The new Patriarch Ilia II, chosen in 1977, was able to fix old churches and even build new ones. At the same time, Georgian nationalists emphasized the Christian nature of their fight against Communist rule. They worked with church leaders, which helped after 1989.

The Church Today

On January 25, 1990, the Patriarch of Constantinople officially recognized the Georgian Orthodox Church's independence. This independence had been practiced or claimed since the 5th century. When Georgia became independent in 1991, the Georgian Orthodox Church saw a big comeback.

The special role of the church in Georgia's history is recognized in the country's Constitution. Its status and relationship with the government were further defined in an agreement signed in 2002. This agreement recognizes that the church owns all its churches and monasteries. It also gives the church a special role in advising the government, especially on education.

Many churches and monasteries have been rebuilt or renovated since Georgia became independent. The church has had good relationships with all three Georgian presidents since independence. However, there have been some disagreements within the church itself. Some members disagree with the church's involvement in the ecumenical movement (working with other Christian churches). Patriarch Ilia II had supported this movement. In 1997, due to strong opposition from some monks, Ilia II stopped the church's participation in international ecumenical groups.

In 2002, 83.9% of Georgia's population identified as Orthodox. At that time, there were 35 areas (called eparchies or dioceses) and about 600 churches. These were served by 730 priests. The Georgian Orthodox Church has about 3.6 million members in Georgia.

How the Church is Organized

The Holy Synod

The Georgian Orthodox Church is managed by the Holy Synod. This is a group of bishops led by the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia. Besides the Patriarch, the Synod has 38 members. These include 25 metropolitan bishops, 5 archbishops, and 7 regular bishops.

Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia

The first head of the Georgian Church to be called Patriarch was Melkisedek I (1010–1033). Since 1977, Ilia II (born in 1933) has been the Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia. He is also the Archbishop of Mtskheta and Tbilisi.

Here is a list of the Catholicos-Patriarchs since the church regained its independence in 1917:

- Kyrion II (1917–1918)

- Leonid (1918–1921)

- Ambrose (1921–1927)

- Christophorus III (1927–1932)

- Callistratus (1932–1952)

- Melchizedek III (1952–1960)

- Ephraim II (1960–1972)

- David V (1972–1977)

- Ilia II (1977–Present)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Iglesia ortodoxa georgiana para niños

In Spanish: Iglesia ortodoxa georgiana para niños

- Christianity in Georgia

- Culture of Georgia

- Religion in Georgia

- Eparchies of the Georgian Orthodox Church