Early Muslim conquests facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Early Muslim conquests |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

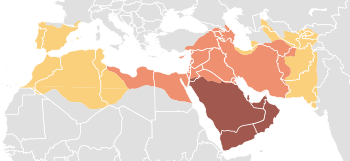

Expansion under Muhammad, 622–632 Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661 Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750 |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

See list

|

See list

Lakhmids Bulgarian Empire Kingdom of Makuria Dabuyid dynasty Khazar Khaganate Turgesh Khaganate Göktürk Khaganate Sogdian rebel Kurdish tribes Romano-Berber kingdoms Kingdom of the Visigoths Kingdom of the Franks Kingdom of the Lombards Duchy of Aquitaine Tang dynasty Brahmin dynasty of Sindh Zunbils Hepthalite principalities |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

See list

Muhammad

Abu Bakr Umar I Uthman Ali Khalid ibn al-Walid Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha Abu Ubayd al-Thaqafi Saad ibn Abi Waqqas Tariq ibn Ziyad Uqba ibn Nafi Muhammad bin Qasim Zuhra ibn al-Hawiyya Hashim ibn Utba Al-Qa'qa' ibn Amr al-Tamimi Abu Musa al-Ashari Ammar ibn Yasir Al-Nu'man ibn Muqrin Hudhayfah ibn al-Yaman Al-Mughira Uthman ibn Abi al-As Asim ibn Amr al-Tamimi Ahnaf ibn Qais Abdallah ibn Amir Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan Shurahbil ibn Hasana Al-Samh ibn Malik al-Khawlani † Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi † Yusuf ibn 'Abd al-Rahman al-Fihri Amr ibn al-As Zubayr ibn al-Awwam Miqdad bin Al-Aswad Ubadah ibn al-Samit Kharija bin Huzafa Abdallah ibn Sa'd Musa bin Nusayr Hasan ibn al-Nu'man Abd ar-Rahman ibn Rabiah Maslamah ibn Abd al-Malik Al-Jarrah ibn Abdallah † Marwan II Qutayba ibn Muslim Muslim ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi Junayd ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Murri Sawra ibn al-Hurr al-Abani Sa'id ibn Amr al-Harashi Asad ibn Abdallah al-Qasri Nasr ibn Sayyar Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra |

See list

Rostam Farrokhzād † Mahbuzan Huzail ibn Imran Hormuz Anoshagan Andarzaghar Bāhman † Pirouzan Jaban Mihran Hormuzan (POW) Mardan Shah Bahram Isandi Karinz ibn Karianz Wahman Mardanshah Jalinus † Mihran-i Bahram-i Razi Beerzan † Farrukhzad Jabalah Ibn Al-Aiham Tervel of Bulgaria Roderic † Agila II † Ardo † Odo of Aquitaine Charles Martel Childebrand Liutprand Pépin le Bref |

||||||||

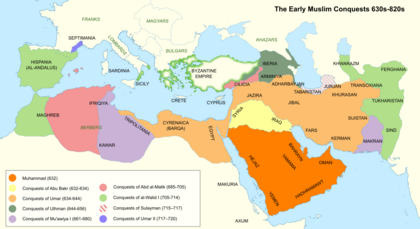

The early Muslim conquests were a series of military campaigns that began in the 7th century. They were started by Muhammad, the founder of Islam. He created a new, united government in Arabia. This new state, called the first Islamic state, grew very quickly.

Under the Rashidun Caliphate and later the Umayyad Caliphate, Muslim rule spread across three continents: Asia, Africa, and Europe. This happened in just about 100 years. Historians say these first Arab conquests were incredibly fast and widespread. They were only matched by the conquests of Alexander the Great, but the Muslim conquests lasted longer.

At their largest, the lands controlled by the Arab Muslims stretched from Spain in the west to India in the east. This included Sicily, most of the Middle East and North Africa, and parts of Central Asia.

These conquests caused huge changes. The Sasanian Empire completely fell apart, and the Byzantine Empire lost a lot of its land. It's hard for historians to know exactly why the Muslims won so easily. This is because only small pieces of information from that time have survived. Some scholars believe that Muhammad's new Islamic state in Arabia, along with a strong shared belief and great organization, helped the early Muslim armies succeed. They built one of the largest empires in history.

Historians also agree that the Sasanian and Byzantine Empires were very tired. They had been fighting each other for many years in the Byzantine–Sasanian wars. This made them weak and easier to conquer. Some people, like Jews and certain Christians in these empires, were unhappy with their rulers. They may have welcomed the Muslim troops. However, some Arab Christians first fought alongside the Byzantines.

Contents

- Understanding the Background

- Armies of the Time

- Major Campaigns

- Taking Control of the Levant (Syria and Palestine): 634–641

- Conquest of Egypt: 639–642

- Conquest of Persia: 633–651

- The First Civil War and the Umayyad Caliphate

- Why Were the Muslim Armies So Successful?

- Conquest of Sindh (India): 711–714

- Conquest of North Africa (Maghreb): 647–742

- Conquest of Spain and Septimania: 711–721

- Conquest of Transoxiana (Central Asia): 673–751

- Other Expeditions

- What Happened After the Conquests?

Understanding the Background

Before the Muslim conquests, two powerful empires, the Byzantine and Sasanian, were constantly at war. These long wars, along with a terrible disease called the Plague of Justinian, made both empires weak. They were not ready for the sudden arrival of the Arab armies.

Life in Arabia Before Islam

Arabia was home to many different groups. Some lived in cities, while others were nomadic Bedouin tribes. Society was based on tribes and clans. The Roman and Persian empires tried to influence Arabia by supporting certain tribes. In return, Arabian tribes sought help from these empires to gain power.

The Lakhmid kingdom, allied with Persia, was taken over by the Persians in 602 AD. This left Persia's southern border open and unprotected. Southern Arabia, especially Yemen, was once very rich from the spice trade. It connected traders from Asia, Africa, and Europe. However, when many people in the Mediterranean became Christian, the demand for spices like frankincense and myrrh dropped. This caused an economic downturn in southern Arabia.

People in pre-Islamic Arabia worshipped many gods, including Allah. Mecca was an important pilgrimage site, home to the Kaaba. Muhammad, a merchant from Mecca, began to have religious visions. He claimed the archangel Gabriel told him he was the last prophet. After conflicts with Mecca's leaders, Muhammad moved to Yathrib, which was renamed Medina. There, he founded an Islamic state. By 630, he had conquered Mecca.

The Roman and Persian Empires at War

The long wars between the Byzantine (Roman) and Sasanian (Persian) empires left them very tired. The last of these wars ended in 628 AD with a Byzantine victory. Emperor Heraclius got back all lost lands. He even returned the True Cross to Jerusalem in 629 AD. This war against the Persians, who worshipped the fire god Ahura Mazda, was seen as a holy war by the Christians.

But neither empire had time to recover. Within a few years, they were overwhelmed by the Arabs. The Arabs were now united by Islam. One historian described their advance as a "human tsunami." The long conflict between the Byzantines and Persians opened the way for Islam to expand.

The Arab Advance Begins

By the late 620s, Muhammad had united much of Arabia under Muslim rule. The first small fights between Muslims and Byzantines happened then. In 629 AD, Arab and Byzantine troops clashed at the Battle of Mu'tah. This happened after Byzantine allies killed a Muslim messenger. Muhammad passed away in 632 AD. Abu Bakr became the first caliph. He gained full control of the Arabian Peninsula after the Ridda Wars. This created a strong Muslim state.

Some Byzantine sources say the Arab invasion happened because of trade restrictions. They claim Arabs killed a Byzantine official they blamed for these rules.

Armies of the Time

Arab Forces

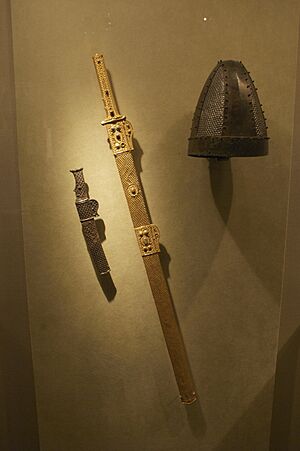

In Arabia, swords from India were highly valued. They were the favorite weapons of the Mujahideen (Muslim fighters). Arab swords were similar to the Roman gladius. Swords and spears were the main weapons. Armor was made of mail (metal rings) or leather.

As the caliphate grew, Muslims learned from the people they conquered. This included the Turkic peoples in Central Asia, the Persians, and the Romans in Syria. Arab Bedouin tribes were good archers. They usually fought on foot, not horseback. Arab armies often placed their archers on the sides during defensive battles.

By the time of the Umayyad caliphate, there was a standing army. This included the best soldiers, called the Ahl al-Sham ("people of Syria"). The caliphate divided its army into jund, or regional armies. These were stationed in different provinces. They were mostly made up of Arab tribes who received monthly pay.

Roman (Byzantine) Forces

The Byzantine army's foot soldiers came from within the empire. But many of their cavalry (horse soldiers) were from the Balkans or Asia Minor. Some were also Germanic mercenaries. Most Roman troops in Syria were local Arabs. After losing Syria, the Romans used Armenian and Arab Christian groups on their border. These groups acted as a "shield" against Muslim raids. The Roman army remained small but professional.

Persian Forces

In the last years of the Sasanian Empire, Persian governors in Central Asia acted like kings. This showed that the power of the Shahinshah (King of Kings) was weakening. Persian society was divided into strict classes. The nobility provided the cavalry. Foot soldiers came from farmers. Many greater Persian nobles also had slave soldiers. Much of the Persian army was made of hired tribal fighters. Persian tactics focused on cavalry, with forces divided into a center and two cavalry wings.

Other Armies

- Ethiopian: Little is known, but they had professional troops and helpers. They used many camels and elephants.

- Berber: These North African people often helped the Roman Army. Their forces used horses and camels. However, they often lacked armor and helmets. Berber armies included their whole communities, which could slow them down.

- Turkic: Historians call the Turkic peoples of Central Asia "most formidable foes." The Jewish Turkic Khazar khanate had strong heavy cavalry. Turkic society was like a feudal system. Their heavily armored cavalry greatly influenced later Muslim tactics. Many Turkic peoples later became Muslim.

- Visigothic: This Germanic people settled in Spain. Their kingdom was based on forces raised by nobles. The Visigoths preferred cavalry and often used fake retreats. The quick Muslim conquest of Spain suggests the Visigothic kingdom had serious weaknesses.

- Frankish: Another Germanic people, the Franks, settled in Gaul (modern France). Their cavalry was also important in wars. Frankish kings expected all men to serve three months in the military each year. They were paid a regular salary.

Major Campaigns

Taking Control of the Levant (Syria and Palestine): 634–641

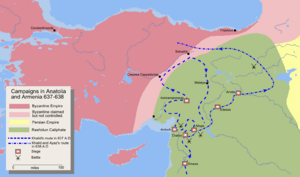

The province of Syria was the first to be taken from Byzantine control. Arab-Muslim raids led the Byzantines to send a large army into southern Palestine. But this army was defeated by Arab forces led by Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Ajnadayn in 634 AD. Khalid had become Muslim around 627 AD and was a very successful general.

The Arabs won another victory at the Battle of Fahl in late 634 or early 635 AD. After a six-month siege, the Arabs took Damascus. However, Emperor Heraclius later recaptured it. At the Battle of the Yarmuk in 636 AD, the Arabs won a major victory, defeating Heraclius. Syria was then left to the Muslims.

After this victory, Arab armies took Damascus again in 636 AD. Baalbek, Homs, and Hama soon followed. But other fortified towns kept fighting. Jerusalem fell in 638 AD, and Caesarea in 640 AD.

Jerusalem's defenders surrendered after a two-year siege. Caliph Umar promised to allow Christians to practice their faith. He also promised not to turn churches into mosques. The loss of Jerusalem, a holy city for Christians, caused much sadness in the Christian world.

In the mountains of Asia Minor, the Muslims had less success. The Romans used "shadowing warfare." They avoided direct battles. People retreated into castles when Muslims invaded. Roman forces instead ambushed Muslim raiders as they returned to Syria with goods and captives. The Romans also created a "no man's land" near the border. They evacuated everyone and destroyed the countryside. This meant invading armies would find no food.

Conquest of Egypt: 639–642

Egypt was very important to the Byzantine Empire. It produced a lot of grain and had naval shipyards. The Muslim general Amr ibn al-As began conquering Egypt in 639 AD. Most Roman forces in Egypt were local Copts. They were more like a police force. Egypt was thought to be safe because it was surrounded by desert.

Amr entered the Sinai in December 639 AD. He took Pelusium and defeated a Roman attack. The Arabs did not go to Alexandria, the capital. Instead, they went to a major fortress called Babylon near modern-day Cairo. The Arabs won a big victory at the Battle of Heliopolis in 640 AD. But they found it hard to advance further. Cities in the Nile Delta were protected by water. Amr also lacked the tools to break down city walls.

The Arabs besieged Babylon. Its starving defenders surrendered on April 9, 641 AD. The last major city to fall was Alexandria, in September 642 AD. Historians say the conquest of Egypt was one of the fastest and most complete. In 644 AD, the Romans briefly recaptured Alexandria with a sea attack. But the Arabs soon took it back. Controlling Egypt meant the caliphate had plenty of grain. This helped it become very prosperous.

The Roman Empire had always controlled the Mediterranean and Black Sea with strong naval bases. In 652 AD, the Arabs won their first sea victory near Alexandria. This led to a temporary Muslim takeover of Cyprus. Yemeni sailors were brought to Alexandria to build an Islamic fleet.

The Muslim fleet was based in Alexandria. It used Acre, Tyre, and Beirut as forward bases. Yemeni sailors were the core of the fleet. But the shipbuilders were from Iran and Iraq. In the Battle of the Masts in 655 AD, Muslims defeated the Roman fleet. As a result, both sides expanded their navies, leading to a naval arms race. From the early 8th century, the Muslim fleet raided Roman coastlines every year.

Both sides looked for new technology. Muslim warships had a larger front section for stone-throwing machines. The Romans invented Greek fire, a burning liquid. This led Muslims to cover their ships with wet cotton. A big problem for the Muslim fleet was a lack of wood. So, they built bigger warships instead of many smaller ones.

Conquest of Persia: 633–651

After an Arab attack into Persian lands, the Persian shah Yazdgerd III raised an army. But many local governors refused to help. The Persians suffered a huge defeat at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah in 636 AD. This battle lasted several days near the Euphrates river in Iraq. The Persian army was destroyed. The Persians had removed their Arab buffer state, leaving their desert border exposed.

After al-Qadisiyyah, Arab-Muslims controlled all of Iraq, including Ctesiphon, the Sasanian capital. The Persians did not have enough forces to stop the Arabs in the Zagros Mountains. Their best army was lost at al-Qadisiyyah. The Persian forces retreated, and the Arab army followed them across Iran. The Sasanian Empire's fate was sealed at the Battle of Nahāvand in 642 AD. Muslims call this crushing victory the "Victory of Victories."

After Nahavand, the Persian state collapsed. Yazdgerd III fled further east. He was killed by a local ruler in 651 AD. The conquerors slowly took control of Persia's vast lands. This included many towns and fortresses. In Afghanistan, Muslims faced fierce resistance from Buddhist tribes. Despite completely defeating Iran, Muslims learned much from the vanished Sasanian state.

The First Civil War and the Umayyad Caliphate

Early on, Muslims realized they needed to write down Muhammad's sayings and story. Most people in Arabia could not read or write. The Arabs had a strong tradition of oral history. To preserve Muhammad's story, Abu Bakr ordered scribes to write it down. This became the Quran.

Later, disputes arose over different versions of the Quran. By 644 AD, different versions were used in different cities. To solve this, Caliph Uthman declared one version, held by Muhammad's widow Hafsa, as the official one. This upset some Muslims. Also, Uthman showed favoritism to his own clan, the Banu Umayya, in government jobs. This led to a revolt in Medina in 656 AD and Uthman's death.

Founding the Umayyad Caliphate

Uthman's successor, Ali, faced a civil war called the fitna. The governor of Syria, Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, rebelled against him. During this time, the Muslim conquests paused as armies fought each other. The fitna ended in January 661 AD when Ali was killed. This allowed Mu'awiya to become caliph and start the Umayyad dynasty. This civil war also marked the beginning of the split between Shia Muslims (who supported Ali) and Sunni Muslims (who opposed him).

Mu'awiya moved the capital from Medina to Damascus. This greatly changed the caliphate's politics and culture. Mu'awiya continued expanding the empire. He invaded Central Asia and tried to conquer Constantinople, the Byzantine capital. In 670 AD, a Muslim fleet took Rhodes and then besieged Constantinople. This siege, from 670 to 677 AD, was more of a blockade. It failed because Constantinople's strong walls, built in the 5th century, held firm.

Most people in Syria remained Christian. A large Jewish minority also stayed. Both groups taught the Arabs much about science, trade, and arts. The Umayyad caliphs are remembered for a "golden age" in Islamic history. They built the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. They also made Damascus the capital of a powerful empire. This empire stretched from Portugal to Central Asia.

Why Were the Muslim Armies So Successful?

Historians have many ideas about why the early conquests happened so quickly. Some early Christian writers thought it was God punishing Christians for their sins. Early Muslim historians believed it showed the conquerors' strong religious faith and God's favor.

Some historians suggest the conquests started as unplanned raids after the Ridda Wars. These raids were then turned into a war of conquest by the caliphs. Others argue the conquests were planned by Muhammad himself. One scholar, Fred Donner, says Islam changed Arabian society. It gave rise to a state that could expand its power. Muslim forces were often outnumbered. But they were fast, well-organized, and highly motivated.

Another main reason was the weakness of the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. Their long wars against each other had exhausted them. A plague also hit densely populated areas, making it hard to find new soldiers. The Arab armies, however, could recruit from nomadic groups. The Sasanian Empire also faced a crisis of confidence after losing to the Byzantines.

The Arabs gained an advantage when Christian Arab tribes, who had fought for the empires, switched sides. Arab commanders also often made deals. They promised to spare lives and property if cities surrendered. They also offered tax breaks to groups who helped them militarily. The Byzantine Empire's persecution of certain Christians in Syria and Egypt also made these communities more open to the Arabs. The Arabs allowed them to practice their faith if they paid taxes.

The conquests were made stronger by many Arab people moving into the conquered lands. The Sasanian Empire could not recover because Persia was geographically and politically disconnected. This made it hard to organize resistance once Sasanian rule fell. The difficult mountains of Anatolia also made it hard for the Byzantines to launch a large attack to get back their lost lands.

Conquest of Sindh (India): 711–714

There were small Arab raids towards India in the 660s. A small Arab base was set up in the dry region of Makran in the 670s. But the first large Arab campaign in the Indus valley happened in 711 AD. General Muhammad bin Qasim invaded Sindh after marching through Makran. Three years later, Arabs controlled all of the lower Indus valley. Most towns surrendered peacefully. But there was strong resistance in other areas, like from the forces of Raja Dahir at Debal. Arab attacks south from Sindh were stopped by Indian kingdoms.

Conquest of North Africa (Maghreb): 647–742

Arab forces began raiding Cyrenaica (modern northeast Libya) soon after conquering Egypt. Byzantine rule in northwest Africa was mostly along the coast. Independent Berber groups controlled the rest. In 670 AD, Arabs founded Qayrawan. This gave them a base for further expansion. Muslim historians say General Uqba ibn Nafi conquered lands all the way to the Atlantic coast. But this seems to have been a temporary advance.

Berber chiefs like Kusayla and a mysterious leader called Kahina (a prophetess) resisted Muslim rule. But the details are unclear. Arab forces captured Carthage in 698 AD and Tangiers by 708 AD. After Tangiers fell, many Berbers joined the Muslim army. In 740 AD, a major Berber revolt shook Umayyad rule. The caliphate finally crushed the rebellion in 742 AD. But local Berber rulers began to break away from central control.

Conquest of Spain and Septimania: 711–721

The Muslim conquest of Spain is hard to study because there are few reliable sources. After the Visigothic king of Spain, Wittiza, died in 710 AD, the kingdom was divided. His son, Akhila, fled to Morocco. Muslim stories say he asked the Muslims to invade Spain. From summer 710 AD, Muslim forces in Morocco made successful raids into Spain. This showed how weak the Visigothic state was.

The Muslim Berber commander, Tariq ibn Ziyad, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar in 711 AD. He had an army of Arabs and Berbers. Most of the 15,000 invaders were Berbers. The Arabs were an "elite" force. Ziyad landed on the Rock of Gibraltar on April 29, 711 AD. After defeating King Roderic on July 19, 711 AD, Muslim forces captured cities one by one. The capital, Toledo, surrendered peacefully. Some cities made deals to pay taxes. Local nobles kept some power. The Spanish Jewish community welcomed the Muslims. They saw them as liberators from the Catholic Visigothic kings.

In 712 AD, another larger force from Morocco, led by Musa Ibn Nusayr, joined Ziyad's army. By 713 AD, Spain was almost entirely under Muslim control. In 714 AD, Ziyad was called to Damascus to explain his campaign. He was later imprisoned. Over the next ten years, Muslims captured Barcelona and Narbonne. They also raided Toulouse and Burgundy.

The last major raid north ended with a Muslim defeat at the Battle of Tours in 732 AD. The Franks, led by Charles Martel, won this battle. This victory is often seen as stopping the Muslim conquest of France. However, the Umayyad force was mainly raiding for plunder, not trying to conquer France. The battle itself is not well-documented. It happened between October 18 and 25, 732 AD. Martel's victory ended any plans to conquer France. But a series of Berber revolts in North Africa and Spain against Arab rule may have played a bigger role in stopping expansion north of the Pyrenees.

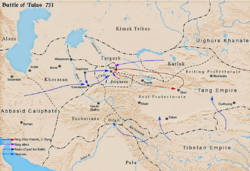

Conquest of Transoxiana (Central Asia): 673–751

Transoxiana is a region northeast of Iran, beyond the Amu Darya river. It includes modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and parts of Kazakhstan. Early attacks aimed at Bukhara (673 AD) and Samarqand (675 AD). These resulted in promises of tribute payments. In 674 AD, a Muslim force attacked Bukhara. The local Sogdians agreed to recognize the Umayyad caliph and pay tribute.

The campaigns in Central Asia were "hard fought." The Buddhist Turkic peoples strongly resisted being brought into the caliphate. China, which saw Central Asia as its own area of influence due to the Silk Road, supported the Turkic defenders. Further advances were stopped for 25 years by political problems within the Umayyad caliphate.

Then, there was a decade of fast military progress. This was under the new governor of Khurasan, Qutayba ibn Muslim. He conquered Bukhara and Samarqand between 706 and 712 AD. The expansion slowed when Qutayba was killed in an army revolt. The Arabs were then on the defensive against an alliance of Sogdian and Türgesh forces, supported by Tang China. However, new troops from Syria helped turn the tide. Most lost lands were retaken by 741 AD. Muslim rule over Transoxania was made strong in 751 AD. This happened when a Chinese-led army was defeated at the Battle of Talas.

Other Expeditions

Cyprus, Armenia, and Georgia

In 646 AD, a Byzantine naval force briefly recaptured Alexandria. The same year, Mu'awiya, the governor of Syria, ordered a fleet to be built. Three years later, it raided Cyprus. Another raid in 650 AD led to a treaty. Cypriots gave up many of their riches and captives. In 688 AD, Cyprus became a shared territory between the caliphate and the Byzantine Empire for almost 300 years.

In 639–640 AD, Arab forces began moving into Armenia. Armenia had been divided between the Byzantine and Sasanian empires. Historians disagree on the exact events that followed. Control of the region may have changed hands several times. Muslim rule was finally established by 661 AD. But it was not very strong. Armenia saw a period of cultural growth over the next century. Like Armenia, Arab advances into other Caucasus regions, like Georgia, aimed to get tribute payments. These areas kept a lot of their independence. This period also saw clashes with the Khazar kingdom. The Khazars fought the caliphate for control of the Caucasus.

Failed Attacks into Greece and Afghanistan

Some Muslim military efforts completely failed. Despite a naval victory over the Byzantines in 654 AD, a later attempt to besiege Constantinople failed. A storm damaged the Arab fleet. Later sieges of Constantinople in 668–669 AD (or 674–678 AD) and 717–718 AD were stopped. This was thanks to the newly invented Greek fire. In the east, Arabs gained control of most Sasanian-controlled areas of modern Afghanistan. But the Kabul region resisted many invasion attempts. It remained unconquered for two centuries.

End of the Major Conquests

By the mid-8th century, Muslim armies met natural barriers and strong states. These stopped further military progress. The wars brought fewer rewards for fighters. More and more soldiers left the army for civilian jobs. The rulers' focus also shifted. They moved from conquering new lands to managing the empire they already had. While some new lands were gained later, like Sicily and Crete, the period of rapid, central expansion ended. Further spread of Islam would be slower. It would happen through local rulers, missionaries, and traders.

What Happened After the Conquests?

Their Importance

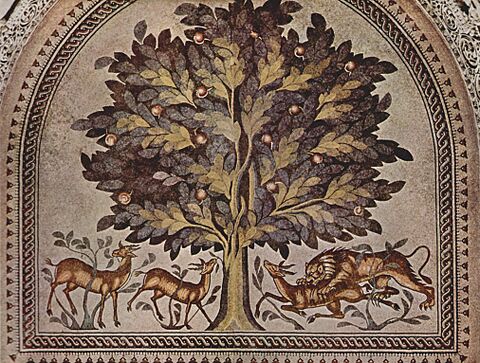

Historians say the Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries were "one of the most significant events in world history." They led to the creation of "a new civilization," the Islamic and Arabized Middle East. Islam, which was once only in Arabia, became a major world religion. A mix of Arab, Roman, and Persian ideas led to new styles of art and architecture.

Historian Edward Gibbon wrote that the Arabian empire stretched for a very long distance. It went from Central Asia and India in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. He noted that Islam brought a similar way of life and beliefs across this huge area. The language and laws of the Quran were studied everywhere. People from different regions felt like countrymen. The Arabic language became common in all lands west of the Tigris river.

Social and Political Changes

The military victories led to the spread of Arab culture and religion. Many Arab families and tribes moved from Arabia into the Middle East. The Arabs already had a complex society. People from Yemen brought farming, city life, and royal traditions. Others had experience working with empires. Soldiers came from both nomadic and settled tribes. Leaders mostly came from the merchant class of the Hejaz.

Two main policies were put in place by the second caliph, Umar (634–644 AD). First, Bedouins were not allowed to harm farming in the conquered lands. Second, leaders would work with local elites. Arab-Muslim armies were settled in separate areas or new garrison towns. Examples include Basra, Kufa, and Fustat. Kufa and Fustat became new administrative centers for Iraq and Egypt. Soldiers were paid and not allowed to take land. Arab governors oversaw taxes. But they generally left the old religious and social order alone. At first, many provinces kept a lot of independence.

Over time, the conquerors wanted more control. They made the existing government systems work for the new rulers. This involved some changes. In the Mediterranean, city-states were replaced by a system that separated town and country administration. In Egypt, independent estates were removed for a simpler system. In the early 8th century, Syrian Arabs began replacing Coptic officials. Taxes on groups changed to taxes on individuals. In Iran, cities like Isfahan grew larger due to changes in administration. Local nobles in Iran, who were once very independent, became part of the central government.

New Arab Settlements

Society in the new Arab settlements slowly became divided by wealth and power. It was also organized into new community groups. These groups kept old clan names but were only loosely based on family ties. Arab settlers took on civilian jobs. In eastern regions, they became landowners. At the same time, the differences between conquerors and local people started to fade. In Iran, Arabs largely adopted local culture. They learned Persian, followed customs, and married Persian women.

In Iraq, non-Arab settlers moved to garrison towns. Soldiers and officials from the old governments sought opportunities with the new rulers. People who were servants or farmers also moved there. They hoped to escape harsh conditions in the countryside. Non-Arab converts to Islam joined Arab-Muslim society. This happened through a system called clientage (mawali). Powerful people offered protection in exchange for loyalty. These clients were seen as part of the clan. Clans became more divided by wealth. For example, some noble clans had Persian cavalry units as their clients. Other clans had servants. Servants often became clients of their former masters when they were freed.

Historians once thought there were mass conversions to Islam right after the conquests. But there is no evidence for this. The first groups to convert were Christian Arab tribes. Some of them kept their religion even while serving in the caliphate's army. Then, former elites of the Sasanian empire converted. This helped them keep their old privileges. Over time, as non-Muslim elites weakened, more people converted. Conversion offered economic benefits and social mobility.

By the early 8th century, conversion became a policy issue for the caliphate. Religious leaders supported it. Many Arabs accepted that Arabs and non-Arabs were equal. However, conversion brought economic and political advantages. Muslim elites did not want their privileges reduced. Policies towards converts varied by region and changed with different caliphs. These issues caused opposition from non-Arab converts. Many of them were soldiers. This helped lead to the civil war that ended the Umayyad dynasty.

Taxes and Converting to Islam

The Arab conquerors learned from the mistakes of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires. Those empires had tried to force an official religion on their people. This caused anger and made the Muslim conquests more acceptable. Instead, the new empire generally respected the traditional Middle Eastern idea of different religions living together. This was not about equality, but one group being dominant.

After the fighting, the early caliphate was generally tolerant. People of all backgrounds and religions mixed in public life. Before Muslims built mosques in Syria, they used Christian churches as holy places. They shared them with local Christians. In Iraq and Egypt, Muslim leaders worked with Christian religious leaders. Many churches were repaired and new ones built during the Umayyad era.

The first Umayyad caliph, Mu'awiyah, tried to show conquered people he was not against their religion. He sought support from Christian Arab elites. There is no sign of the state openly promoting Islam until the rule of Abd al-Malik (685–705 AD). Then, verses from the Quran and references to Muhammad suddenly appeared on coins and official papers. This change aimed to unite the Muslim community after a civil war. It also rallied them against their main enemy, the Byzantine Empire.

A further policy change happened during the rule of Umar II (717–720 AD). The failure of the siege of Constantinople in 718 AD, with many Arab casualties, led to strong anger among Muslims towards Byzantium and Christians. At the same time, many Arab soldiers left the army for civilian jobs. They wanted to show their high social status. These events led to rules that limited non-Muslims. These rules were similar to Byzantine limits on Jews and Sasanian rules about clothing for different classes.

In the following decades, Islamic legal scholars created laws. These laws gave other religions a protected but lower status. Islamic law classified people by their religion, like the Byzantine Empire. This was different from the Sasanian model, which focused more on social class. In theory, the caliphate severely restricted paganism. But in practice, most non-Abrahamic groups in former Sasanian lands were seen as "People of the Book" (ahl al-kitab). They were given protected (dhimmi) status.

Jews and Christians

In Islam, Christians and Jews are called "Peoples of the Book." Muslims accept Jesus Christ and Jewish prophets as their own. This gave them respect that was not given to "heathen" peoples in Iran, Central Asia, and India. In places like the Levant and Egypt, both Christians and Jews could keep their churches and synagogues. They also kept their own religious organizations. In return, they paid the jizya tax.

Sometimes, caliphs made grand gestures. For example, they built the famous Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem (690–692 AD). It was built on the site of the Jewish Second Temple, destroyed by the Romans in 70 AD. This mosque partly celebrated Arab victories over the two empires.

Christians who disagreed with the official Roman Empire's beliefs often preferred Muslim rule. It meant an end to their persecution. Jewish and Christian communities in the Levant and North Africa were often better educated than their conquerors. So, they often worked as civil servants in the early caliphate. However, a saying attributed to Muhammad, "Two religions may not dwell together in Arabia," led to different policies in Arabia. There, conversion to Islam was required rather than just encouraged. Except for Yemen, all Christian and Jewish communities in Arabia "completely disappeared." The Jewish community of Yemen survived because Yemen was not seen as part of Arabia proper.

Historian Mark R. Cohen writes that the jizya tax paid by Jews under Islamic rule gave them "surer protection from non-Jewish hostility." This was better than what Jews had in the Latin West. There, Jews paid many high and unfair taxes for official protection. Their treatment was based on charters that new rulers could change or refuse to renew. The Pact of Umar stated that Muslims must "guard" the dhimmis and "put no burden on them greater than they can bear." This pact was not always followed, but it remained a key part of Islamic policy for a long time.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |