Constantine V facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Constantine V |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Romans | |

Solidus of Constantine V.

|

|

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 18 June 741 – 14 September 775 |

| Coronation | 31 March 720 |

| Predecessor | Leo III the Isaurian |

| Successor | Leo IV the Khazar |

| Rival emperors | Artabasdos (741–43) Nikephoros (741–43) |

| Born | July 718 Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 14 September 775 (aged 57) |

| Wives |

|

| Issue | Leo IV Nikephoros Christopher Niketas Eudokimos Anthimos Anthousa |

| Dynasty | Isaurian |

| Father | Leo III the Isaurian |

| Mother | Maria |

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity |

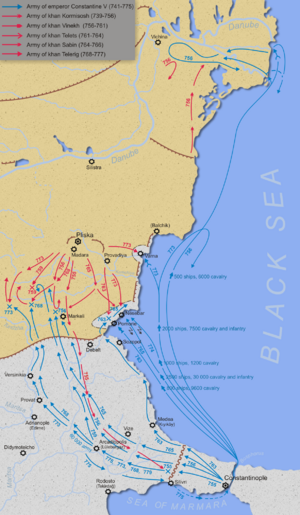

Constantine V (born July 718 – died 14 September 775) was a powerful Byzantine emperor who ruled from 741 to 775. His time as emperor helped make the Byzantine Empire safer from outside attacks. He was a skilled military leader. Constantine used a civil war happening in the Muslim world to attack the Arab border.

With the eastern border secure, he led many battles against the Bulgars in the Balkans. His military actions and his plan to move Christian people from the Arab border to Thrace made the empire's control over its Balkan lands stronger. He also made important changes to the military and how the government was run.

His reign was also known for big religious disagreements. Constantine strongly supported Iconoclasm. This was a belief that religious images should not be worshipped. He also opposed monks and nuns. Because of this, some people at the time and many later writers spoke badly about him.

Contents

Early Life of Constantine V

Constantine was born in Constantinople, the capital city. He was the son of Emperor Leo III and Empress Maria. When he was just two years old, in 720, his father made him a co-emperor. He was crowned by Patriarch Germanus I.

In the Byzantine Empire, more than one emperor could rule at the same time. This helped make sure the next emperor was chosen smoothly. To celebrate his son's crowning, Leo III created a new silver coin called the miliaresion. This coin quickly became important for the Byzantine economy.

In 726, Constantine's father released a new set of laws called the Ecloga. These laws were said to be from both father and son. Constantine later married Tzitzak, the daughter of the Khazar ruler Bihar. The Khazars were an important ally of the Byzantines. His new wife was baptized and given the name Irene, which means "peace." When his father died, Constantine became the sole emperor on June 18, 741.

Historical records mention that Constantine had a long-term health problem. Some people who rebelled against him used this to question if he was fit to be emperor.

Constantine's Reign as Emperor

Rebellion of Artabasdos

Right after Constantine became emperor in 741, his brother-in-law Artabasdos rebelled. Artabasdos was a powerful military governor. He controlled two important provinces, the Opsikion and Armeniac themes.

Artabasdos attacked Constantine when their armies were supposed to join for a campaign. Constantine managed to escape and found safety in Amorion. Meanwhile, Artabasdos marched to Constantinople. With support from some officials, he was crowned emperor. Constantine had the support of other provinces, while Artabasdos had his own troops and the province of Thrace.

The two emperors prepared for battle. Artabasdos attacked Constantine in May 743 but was defeated. Three months later, Constantine defeated Artabasdos's son. In early November, Constantine entered Constantinople after a siege. He quickly dealt with his opponents. Patriarch Anastasius was shamed in public but allowed to keep his job. Artabasdos and his sons were captured and lost their sight. They were then sent to a monastery.

Constantine's Support for Iconoclasm

Like his father, Constantine strongly supported iconoclasm. This was a religious movement that believed people should not worship religious images, called icons. Iconoclasts wanted to remove or destroy these images. Those who defended the worship of images were called iconodules.

Constantine believed that God or Christ could not be truly shown in a picture. He argued that if God is "uncircumscribable" (meaning He cannot be limited or contained), then He cannot be properly drawn or painted. Since Christians believe Christ is God, Constantine thought Christ also could not be shown in images. The Emperor was very involved in these religious debates. He even wrote thirteen papers about his views.

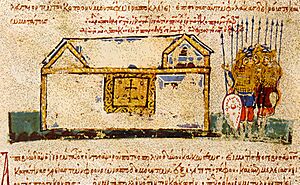

In February 754, Constantine called a meeting of bishops at Hieria. Only bishops who supported iconoclasm attended. They agreed with Constantine's ideas about images and declared them wrong. They also chose a new iconoclast patriarch. However, the council did not agree with all of Constantine's extreme views. They still honored Mary, mother of Jesus, as the "Mother of God" and respected saints. They also said churches should not be damaged in the effort to remove icons.

After the council, a campaign began to remove images from churches. People who supported icons were removed from the court and government. Monasteries often supported icons and did not contribute much to the state. So, Constantine specifically targeted them. He took their property for the government or the army. His general, Michael Lachanodrakon, led many of these actions. He threatened monks with blinding or exile. Some monks and nuns were even forced to marry in public to shame them.

An abbot named Stephen Neos, who supported icons, was beaten to death. Many monks fled to Italy and Sicily. The strong resistance from icon-supporters led to some plots against the Emperor. In 765, Constantine punished eighteen high-ranking officials accused of treason. Some were executed, some lost their sight, and others were sent away. Patriarch Constantine II of Constantinople was removed from his position and later beheaded.

By the end of Constantine's rule, iconoclasm had gone very far. It even questioned the use of relics and prayers to saints. However, some historians now believe that the destruction of images and relics was not as widespread as later writings claimed. Many icons were hidden and survived. The general culture of religious art seems to have continued. Later writings by icon-supporters often made the destruction seem worse than it was.

Icon-supporters believed Constantine's death was a punishment from God. After icon-worship was fully restored in the 9th century, Constantine's body was removed from the imperial tomb.

Domestic Policies and Administration

Constantine wanted to be popular with the people. He often used the hippodrome, where exciting chariot races took place, to influence the people of Constantinople. He worked with the "circus factions," who controlled the racing teams and had a lot of social power. The hippodrome became a place where war captives and political enemies were publicly shamed.

Constantine's main supporters were the common people and the army. He used their support against his icon-supporting opponents, especially in monasteries and the government. Iconoclasm was not just the emperor's belief; it also had a lot of public support. Constantine's actions against icon-supporters might have been to keep the people and army happy. Monasteries did not pay taxes, and monks did not serve in the army. So, the Emperor's dislike for them might have been more about money and manpower than just religion.

Constantine continued the government and money reforms started by his father, Leo III. Military governors (called strategoi) were very powerful. They controlled many resources in their large provinces, which sometimes allowed them to rebel. The Opsikion province was where Artabasdos's rebellion started. Constantine made this province smaller by dividing it into new ones. This meant that no single governor had too much power, making rebellions harder.

Constantine also created a small, professional central army called the imperial tagmata (regiments). He trained and expanded palace guards into serious fighting units. These tagmata were better trained, paid, and equipped than the provincial armies. They were based near the capital and directly controlled by the Emperor. This helped prevent military rebellions that often came from regional loyalties.

Constantine's financial management was very good. His enemies accused him of being too harsh with taxes. However, the empire was wealthy, and Constantine left a lot of money for the next emperor. More land was farmed, and food became cheaper. For example, wheat production in Thrace tripled between 718 and 800. Constantine's court was grand, with beautiful buildings. He also encouraged non-religious art to replace the religious art he had removed.

Constantine built several important structures in the Great Palace of Constantinople. This included the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos and the porphyra. The porphyra was a room lined with purple stone. It was where empresses gave birth to imperial children. Constantine's son Leo was the first child born there. This gave him the special title porphyrogénnētos, meaning "born in the purple." This title showed he was a truly legitimate prince.

Constantine also rebuilt the famous Hagia Eirene church in Constantinople. It had been badly damaged by an earthquake in 740. This building still has rare examples of church decorations from the iconoclast period.

With many children, Constantine set up clear titles for his family members. Only his oldest son, Leo, became co-emperor (in 751). His younger sons received titles like caesar or nobelissimos.

Campaigns Against the Arabs

In 746, Constantine took advantage of problems in the Umayyad Caliphate. He invaded Syria and captured Germanikeia, his father's birthplace. He also took back the island of Cyprus. He moved some of the local Christian people to imperial land in Thrace. This helped strengthen the empire's control over that region. In 747, his navy destroyed the Arab fleet near Cyprus.

That same year, a serious outbreak of plague hit Constantinople. This stopped Byzantine military actions for a while. Constantine moved to Bithynia to avoid the disease. After the plague ended, he moved people from mainland Greece and the Aegean islands to Constantinople to replace those who had died.

In 751, he led an invasion into the new Abbasid Caliphate. Constantine captured and destroyed cities like Theodosiopolis and Melitene. He again moved some of their people to the Balkans. These eastern campaigns did not gain much land permanently. However, under Constantine, the empire began attacking the Arabs after more than a century of mostly defending itself.

Constantine's main goal in the east was to move Christian people from outside his borders to resettle Thrace. Also, by emptying the land beyond the eastern borders, he created a "no-man's land." This made it harder for Arab armies to gather and get supplies. This made Byzantine Anatolia safer. His military fame was so great that in 757, just the rumor of his presence made an Arab army retreat. That same year, he agreed to a truce and prisoner exchange with the Arabs. This freed his army for campaigns in the Balkans.

Events in Italy

While Constantine was busy with wars elsewhere, and because he saw Italy as less important, the Lombard king Aistulf captured Ravenna in 755. This ended over two centuries of Byzantine rule in central Italy. Constantine's lack of interest in Italian affairs had big and lasting effects.

Pope Stephen II, seeking protection from the Lombards, personally asked the Frankish king Pepin the Short for help. Pepin defeated Aistulf and helped Stephen return to Rome with an army. This started the Frankish involvement in Italy. It eventually led to Pepin's son Charlemagne becoming Holy Roman Emperor. It also began the Pope's temporal rule in Italy with the creation of the Papal States.

Constantine sent several messages to the Lombards, Franks, and the Pope asking for Ravenna to be returned. However, he never tried to take it back by military force.

Repeated Campaigns Against the Bulgarians

Successes in the east allowed Constantine to focus on the Balkans. He wanted to make Thrace more prosperous and secure by moving Christian people there from the east. This arrival of new settlers and the rebuilding of border forts worried Bulgaria, the empire's northern neighbor. This led to clashes in 755.

Kormisosh of Bulgaria raided as far as the Anastasian Wall (a defense line near Constantinople). But Constantine defeated him in battle. Constantine then began a series of nine successful campaigns against the Bulgarians. He won a victory over Kormisosh's successor, Vinekh, at Marcellae in 756. In 759, Constantine was defeated at the Battle of the Rishki Pass, but the Bulgarians could not use their victory.

Constantine campaigned against the Slav tribes in Thrace and Macedonia in 762. He moved some tribes to the Opsician province in Anatolia. Some Slavs even asked to be moved away from the troubled Bulgarian border. A Byzantine source said that 208,000 Slavs moved from Bulgarian areas into Byzantine land and settled in Anatolia.

A year later, he sailed to Anchialus with 800 ships and many soldiers. He won a big victory over Khan Telets. Many Bulgarian nobles were captured and later killed outside the Golden Gate of Constantinople. Telets was killed after his defeat. In 765, the Byzantines invaded Bulgaria again. During this campaign, both Constantine's choice for the Bulgarian throne and his opponent were killed. The many victories of Constantine caused a lot of trouble in Bulgaria. Six rulers lost their crowns because they failed in wars against Byzantium.

In 775, the Bulgarian ruler Telerig contacted Constantine. He asked for safety, saying he feared he would have to flee Bulgaria. Telerig asked who he could trust inside Bulgaria. Constantine foolishly told him the names of his secret agents in the country. These Byzantine agents were then quickly eliminated. In response, Constantine started a new campaign against the Bulgarians. During this journey, he developed painful sores on his legs. He died on his way back to Constantinople on September 14, 775. Even though Constantine could not destroy the Bulgarian state, he made the empire's power in the Balkans strong again.

Assessment and Legacy

Constantine V was a very capable ruler. He continued the important changes in finance, government, and military that his father started. He was also a successful general. He not only made the empire's borders secure but also actively fought beyond them. By the end of his reign, the empire had strong finances, a skilled army proud of its wins, and a church that seemed to follow the government's lead.

By focusing on the main parts of the empire, he quietly gave up some distant areas, especially in Italy. These were lost. However, the Roman Church and Italian people strongly disliked iconoclasm. This likely meant that the empire's influence in central Italy would have ended anyway.

Because he supported iconoclasm, Constantine was criticized by writers who supported icons. Later Orthodox historians also spoke badly of him. For example, one writer called him "a monster athirst for blood" and "a ferocious beast." However, to his army and people, he was "the victorious and prophetic Emperor." After a terrible defeat by the Bulgarian Khan Krum in 811, soldiers broke into Constantine's tomb. They begged the dead emperor to lead them once more.

If we look at Constantine's life without the extreme praise from his soldiers or the harsh criticism from icon-supporters, we see he was a strong leader and a talented general. But he was also very strict, unwilling to compromise, and sometimes unnecessarily harsh.

All the historical writings about Constantine that still exist were written by people who supported icons. Because of this, we must be careful about their fairness and accuracy. Especially when they talk about his reasons or the actions of his supporters and opponents. This makes it hard to be completely sure about Constantine's policies or how much he punished icon-supporters.

One old manuscript, written during or just after Constantine's reign, is different. It does not have the extreme insults found in later icon-supporting writings. Instead, the author suggests that icon-supporters had to accept the emperor's iconoclast policies. The author even gives Constantine V traditional religious praise, calling him "Guarded by God" and "Christ-loving emperor."

Family

By his first wife, Tzitzak (who was renamed Irene), Constantine V had one son:

- Leo IV, who became emperor after him. He was crowned in 751.

By his second wife, Maria, Constantine V is not known to have had children.

By his third wife, Eudokia, Constantine V had five sons and a daughter:

- Christopher, a caesar

- Nikephoros, a caesar

- Niketas, a nobelissimos

- Eudokimos, a nobelissimos

- Anthimos, a nobelissimos

- Anthousa (who became a nun and was later known as Saint Anthousa the Younger)

See also

In Spanish: Constantino V para niños

In Spanish: Constantino V para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |