Byzantine Iconoclasm facts for kids

The Byzantine Iconoclasm was a time in the Byzantine Empire when people argued fiercely about religious images, called icons. This period happened twice: the First Iconoclasm from about 726 to 787, and the Second Iconoclasm from 814 to 842. During these times, some leaders and religious figures believed that using icons in worship was wrong.

This belief led to many religious images being destroyed. People who supported icons were sometimes treated badly. The leader of the Western Church, the Pope in Rome, always supported using icons. This disagreement helped to widen the gap between the Eastern (Byzantine) and Western (Roman) parts of the Christian Church.

Iconoclasm means purposely destroying religious images or symbols in a culture. This is usually done for religious or political reasons. People who do this are called iconoclasts. This word comes from Greek and means 'icon breakers'. Today, we sometimes use "iconoclast" for anyone who challenges old ideas.

People who loved and respected religious images were called "iconodules" or "iconophiles". The debate itself was called iconomachy, meaning "struggle over images".

One main reason for iconoclasm came from an old rule in the Ten Commandments. This rule said not to make or worship "graven images" (Exodus 20:4-5). During the Iconoclasm, people argued if this rule meant they couldn't have pictures of holy figures like Jesus, the Virgin Mary, or saints. This debate started because of big social and political changes in the 600s.

Some historians thought that the Islamic religion, which doesn't allow images, influenced the Byzantines. They believed that Byzantine emperors saw the success of Muslim armies and thought God was punishing them for using images. However, this idea is now debated. Women and monks often supported icons. Some people also thought that iconoclasm caused divisions between different groups in Byzantine society.

Contents

Why the Debate Started

By the 500s, Christians believed that saints could help them by praying to God for them. They also believed in a special order of holiness. God was at the top, then the Virgin Mary (called the Theotokos, or "Mother of God"), then saints, then holy living people, and finally everyone else. To get God's favor, Christians would ask saints or the Theotokos to pray for them.

Using relics (holy objects linked to Christ or saints) and holy images (icons) also became very important. People would visit holy places like the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Relics were seen as a way to feel God's presence.

The use of images grew a lot during this time. Mosaics and paintings were everywhere: in churches, homes, and even on city gates. People started to believe that these images had spiritual power. They thought images could show their wishes, teach lessons, or even bleed if attacked.

Around 570, special images called acheiropoieta appeared. These were believed to have been made miraculously, "not by human hands." They were seen as proof that God approved of icons. Two famous ones were the Mandylion of Edessa and the Image of Camuliana. The Image of Camuliana was even believed to have saved Constantinople during a siege in 626. These stories helped the idea that icons had been used since the start of Christianity.

The 600s were a tough time for the Byzantine Empire. This crisis made people use holy images even more. They wanted divine help during uncertain times. This change in worship was a natural development from the people, not something the Church planned. The Church and the emperors later tried to control this popular practice.

The rise of Islam in the 600s also made people think about holy images. Early Islam did not allow images of living things. Some scholars thought Byzantine emperors copied this idea, believing it would make God happy. But this isn't very likely. In fact, Muslim lands often became safe places for people who supported icons.

The iconoclasts wanted to bring the Church back to what they thought was the early Church's strict rule against images. They believed icons could not show both Jesus's divine (God) and human natures at the same time. If an icon only showed Jesus as human, it was wrong. If it tried to show both, it would mix them up, which was also seen as wrong. So, for iconoclasts, all icons were a heresy (a belief against official Church teachings).

Where Iconoclasm Was Found

Newer studies show that iconoclasm wasn't just in the eastern parts of the Empire, near the Arab border. It was found in western areas too, like the Cyclades islands. Meanwhile, eastern areas like Cyprus continued to use icons.

People who supported icons often fled to places far from the emperor's control. This included Italy, Dalmatia, Cyprus, and parts of Anatolia. It's also possible that iconoclasm was strong in eastern Anatolia because the emperors there had military victories against the Arabs and had strong control over the area.

The First Iconoclast Period: 730–787

A big underwater volcano eruption in 726 might have started the controversy. Many people, including Emperor Leo III the Isaurian, thought this was God's punishment. They believed using images was the offense.

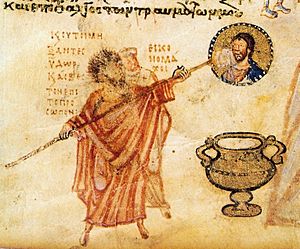

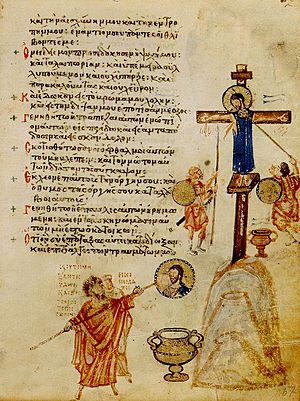

The story goes that between 726 and 730, Emperor Leo III ordered a famous image of Christ removed from the Chalke Gate in Constantinople. He wanted it replaced with a cross. Some people assigned to this task were killed by icon supporters. Later writings suggest Leo might have done this because of military losses to the Muslims and the volcano eruption. He saw these as signs of God's anger.

Leo reportedly called image worship "a craft of idolatry." In 730, he banned the worship of religious images. This ban did not apply to other art, like pictures of the emperor, or religious symbols like the cross. Leo didn't ask the Church for its opinion and was surprised by how much people opposed him. Germanos I of Constantinople, the leader of the Church in Constantinople, either quit or was removed after the ban.

Some letters from Germanos show he was worried the ban would make it seem like the Church had been wrong for a long time. This would give an advantage to Jews and Muslims.

However, some historians now think the debate might have started in the provinces, not at the imperial court. Letters from Germanos in the 720s and 730s show he supported images. He complained that "whole towns and multitudes of people are in considerable agitation over this matter." He even said Emperor Leo III, often called the first iconoclast, was a friend of images. This makes Leo III's true views unclear. Most of what we know about his reign comes from later writings that were against him and his son, Constantine V.

During this early period, the debate was more about practical effects than deep theology. There was no church council about it at first. Leo reportedly took valuable church items decorated with religious figures. But he didn't take harsh action against the former patriarch or bishops who supported icons.

In the West, Pope Gregory III held meetings in Rome and spoke against Leo's actions. In response, Leo took away the Pope's lands in Italy and put them under the control of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Church Councils

Leo III died in 741. His son, Constantine V (741–775), was strongly against images. Even though he was a successful emperor, he is remembered badly in writings because of his opposition to icons. These writings say he was obsessed with hating images and monks. They claim he burned monasteries, destroyed images, and turned churches into stables.

In 754, Constantine called the Council of Hieria. About 330 to 340 bishops attended. This was the first church council mainly about religious images. Constantine was very involved. The council supported iconoclasm, saying that painting living creatures was wrong and went against the teachings of Christ. They declared that anyone who tried to show saints in lifeless pictures was against God. This council claimed to be the "Seventh Ecumenical Council" (a major meeting of the whole Church). But both Orthodox and Catholic Churches do not accept it as legitimate. This is because no patriarchs or representatives from the five main Church centers were there.

The iconoclast Council of Hieria didn't end the debate. Complex arguments for and against icons appeared. Constantine himself wrote against images. Meanwhile, John of Damascus, a monk living outside the Byzantine Empire, became a major defender of icons through his writings.

Some historians think monasteries secretly supported icons. Others disagree, saying many monks followed the emperor's policy. The writings that survive accuse Constantine V of persecuting monks. They say he forced monks to parade in public with women, breaking their vows. Many monks fled to areas outside the Empire's control.

Constantine's son, Leo IV (775–80), was less strict. He tried to find a middle ground. When he died, his wife Irene became ruler for her young son, Constantine VI. Irene called a new church council a year after Leo's death. This council brought back the veneration of images. She might have done this to improve relations with Rome.

Irene started a new council, called the Second Council of Nicaea. It first met in Constantinople in 786 but was stopped by soldiers who supported iconoclasm. The council met again in Nicaea in 787. It overturned the decisions of the iconoclast council of 754. It also claimed the title of the Seventh Ecumenical Council. So, there were two councils called the "Seventh Ecumenical Council": one for iconoclasm, one against it.

Unlike the iconoclast council, the iconophile council included representatives from the Pope. Its decisions were approved by the Pope. The Eastern Orthodox Church sees it as the last true ecumenical council. Icon veneration continued after Empress Irene's rule.

Decision of the Second Council of Nicaea

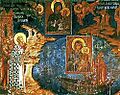

On October 13, 787, the Second Council of Nicaea declared that "venerable and holy images are to be dedicated in the holy churches of God." This included images of Jesus, the Virgin Mary, angels, and all the saints. They said these images should be given "veneration of honor," but not the "true worship" that is only for God. This was like the respect given to the cross, the holy gospels, and other sacred items.

The Second Iconoclast Period: 814–843

Emperor Leo V the Armenian started a second period of Iconoclasm in 815. Again, this might have been because of military losses, which he saw as signs of God's displeasure. He also wanted to copy the military success of Constantine V. The Byzantines had suffered defeats against the Bulgarians. In 813, soldiers even broke into Constantine V's tomb, begging him to return and save the empire.

Soon after becoming emperor, Leo V discussed bringing back iconoclasm. He reportedly said that all emperors who honored images died in revolts or wars. But those who didn't honor images died naturally and stayed in power.

Leo then appointed a group of monks to "look into the old books" about images. They found the decisions of the Iconoclastic Synod of 754. A debate followed between Leo's supporters and those who defended icons, led by Patriarch Nikephoros. No agreement was reached. But Leo was convinced that iconoclasm was right. He had the icon on the Chalke gate replaced with a cross. In 815, a Synod in the Hagia Sophia officially brought back iconoclasm.

Leo was followed by Michael II. In an 824 letter, Michael complained about image worship and practices like making icons godparents to babies. He confirmed the decisions of the Iconoclast Council of 754.

Michael's son, Theophilus, became emperor next. When he died, his wife Theodora ruled for their young son, Michael III. Like Empress Irene before her, Theodora brought back icon veneration in 843 at the Council of Constantinople. She did this on the condition that Theophilus would not be condemned. Since then, the first Sunday of Great Lent in the Orthodox Church is celebrated as the "Triumph of Orthodoxy".

Arguments in the Debate Over Icons

Iconoclast Arguments

Most of what we know about iconoclast arguments comes from writings by those who supported icons. So, it's hard to know how popular iconoclast ideas truly were. The main arguments focused on whether it was right to make pictures of Jesus and other holy figures.

Here were the main points of the iconoclast argument:

- Iconoclasts said it was wrong to make any lifeless image (like a painting or statue) that showed Jesus or a saint. The Council of 754 declared that any likeness made by painters was evil. They said if anyone tried to show Jesus's divine image with colors, they were against God. They also said that showing saints in lifeless pictures was wrong; instead, people should show the saints' virtues in their own lives.

- For iconoclasts, a true religious image had to be exactly like the original, made of the same substance. They believed this was impossible, as wood and paint were empty of spirit. So, for them, the only true "icon" of Jesus was the Eucharist (Communion), which Orthodox and Catholic beliefs say is the Body and Blood of Christ.

- They argued that any true image of Jesus must show both his divine nature (which can't be seen) and his human nature (which can). But if you make an icon of Jesus, you either separate his human and divine natures (which was considered Nestorianism), or you mix them up (which was considered Monophysitism). Both were seen as heresies.

- Iconoclasts saw using icons for religious purposes as a new and wrong idea in the Church, a return to pagan practices. They believed that the devil brought back idolatry disguised as Christianity. They also said it went against old church traditions, pointing to writings that opposed religious images. For example, the Synod of Elvira (around 300 AD) said images should not be in churches.

Iconophile Arguments

The main religious leaders who fought against iconoclasm were the monks John of Damascus and Theodore the Studite. John lived in Muslim territory, so he was safe from the Byzantine emperor.

John of Damascus said he didn't worship matter itself, but "the creator of matter." He also said he respected the matter through which salvation came to him, like the ink in the g gospels, the paint of images, the wood of the Cross, and the body and blood of Jesus. This difference between "worship" (only for God) and "veneration" (respect for holy things) was key for iconophiles.

Here's how iconophiles argued against iconoclasm:

- They said the Bible's rule against images of God was changed when Jesus came to Earth. Jesus was God in human form, so he could be seen. Therefore, they weren't showing the invisible God, but God as he appeared in the flesh. They also pointed to Old Testament examples where God told Moses to make golden statues of cherubim for the Ark of the Covenant and to embroider curtains with cherubim.

- They argued that idols showed false gods, while icons showed real people like Christ or saints. So, images of real people couldn't be idols. This was like the Old Testament rule of only offering sacrifices to God, not to other gods.

- Regarding old writings against images, they said that icons were part of an unwritten oral tradition passed down through the Church. They also pointed to writings from early Church leaders who approved of icons.

- They emphasized acheiropoieta (miraculous icons) and miracles linked to icons. They believed that both Christ and the Virgin Mary had sat for their portraits to be painted.

- Iconophiles also argued that decisions about icons should be made by the Church in a council, not forced by an emperor. They also noted it was foolish to deny God the same honor given to a human emperor, since portraits of emperors were common and iconoclasts didn't oppose them.

Emperors had always been involved in Church matters since Constantine I. This continued throughout the Iconoclast controversy, with some emperors enforcing iconoclasm and two empresses bringing back icon veneration.

In Art

The iconoclastic period greatly reduced the number of Byzantine artworks that survived from before this time. This includes large religious mosaics and portable icons. Many important works in Thessaloniki were lost later in fires and wars.

The simple Iconoclastic cross that replaced a mosaic in the apse of Hagia Irene in Constantinople is a rare survival. Looking closely at other buildings shows similar changes. In Nicaea, photos of the Church of the Dormition (before it was destroyed in 1922) show that a pre-iconoclasm image of the Theotokos was replaced by a large cross. This cross was then replaced by a new Theotokos image. The famous Image of Camuliana in Constantinople seems to have been destroyed, as it is no longer mentioned.

Reaction in the West

The period of Iconoclasm completely changed the relationship between the Pope in Rome and the emperor in Constantinople. For two centuries, popes had been chosen or approved by the emperor. But by the end of the controversy, the Pope approved a new emperor in the West. The Western Church no longer showed its old respect to Constantinople.

Opposition to icons had little support in the West. Rome consistently supported icons. When the arguments started, Pope Gregory II was Pope. He had visited Constantinople and solved earlier issues with Emperor Justinian II. This was the last time a Pope visited the city until 1969. There were already conflicts with Leo III over his high taxes on Papal lands.

The Iconoclast Controversy caused relations between the Pope and the Emperor to get much worse. Pope Gregory III excommunicated all iconoclasts. The Emperor sent an army to Rome, but it failed. In 754, the Emperor took over Papal properties in Sicily, Calabria, and Illyria. In the same year, Pope Stephen II made an alliance with the Frankish Kingdom. This marked the beginning of the end for the Pope's support of the Byzantine Empire.

See also

- Aniconism in Christianity

- Feast of Orthodoxy

- Libri Carolini

Images for kids

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |