Khalid ibn al-Walid facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Khalid ibn al-Walid

خالد ابن الوليد |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Other name(s) | Sayf Allah ('The Sword From The Sword Of Allah') Abu Sulayman |

| Born | Medina |

| Died | 642 Medina or Homs |

| Possible burial place |

The Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque, Homs, Syria

|

| Allegiance | Quraysh (625–627 or 629) Muhammad (627 or 629–632) Rashidun Caliphate (632–638) |

| Service/ |

Rashidun army |

| Years of service | 629–638 |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Spouse(s) | Asma bint Anas ibn Mudrik Umm Tamim bint al-Minhal |

| Children | Abd al-Rahman Muhajir Sulayman |

Khalid ibn al-Walid (born around 585, died 642) was a very important army leader in early Islamic history. He served under the first two leaders of the Muslim community, Abu Bakr and Umar. Thanks to his military skills, the Arabian Peninsula was united under one government, called the Caliphate, for the first time.

Khalid ibn al-Walid was from the Meccan tribe of Quraysh. His clan first opposed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Khalid played a big part in the Meccan victory against the Muslims at the Battle of Uhud.

Later, Khalid became a Muslim. He joined Muhammad after the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah. He fought in many battles for Muhammad, including the Battle of Mu'tah. This was the first battle between the Romans and the Muslims. Khalid said the fighting was so fierce that he broke nine swords. Because of his bravery, he earned the title "Sayf Allah" (pronounced "Saif-ullah"), which means "The Sword of Allah".

Khalid captured the kingdom of Al-Hirah, which was allied with the Persian Empire. He also defeated Persian forces during his journey through Iraq (ancient Mesopotamia). Later, he was sent to the western front to capture Roman Syria. He also fought against the Ghassanids, who were allied with the Byzantine Empire.

Even though the Caliph Umar later removed him from supreme command, Khalid remained an important leader. He led the Muslim forces against the Byzantines during the early Byzantine–Arab Wars. Under his command, Damascus was captured in 634. A major victory against the Byzantine forces happened at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636. This led to the conquest of the Bilad al-Sham region. In 638, he retired from military service.

Historians generally see Khalid as one of the most skilled generals of early Islam. He is remembered throughout the Arab world. Islamic tradition praises Khalid for his clever battle plans and strong leadership during the early Muslim conquests.

Contents

Early Life and Training

Khalid was born around 585 in Mecca. His father, Walid ibn al-Mughirah, was the leader of the Banu Makhzum clan. This clan was part of the Quraysh tribe. When Khalid was a baby, he was sent to live with a Bedouin tribe in the desert. This was a common tradition for the Quraysh. He returned to Mecca when he was about five or six years old. As a child, Khalid had a mild case of smallpox, which left some marks on his left cheek.

The Banu Makhzum clan was known for its warriors. They were among the best horsemen in Arabia. Khalid learned to ride horses and use weapons like the spear, lance, bow, and sword. The lance was his favorite weapon. From a young age, he was known as a strong warrior and wrestler among the Quraysh. Khalid was also a cousin of Umar, who would later become the second caliph.

Early Military Career

Fighting Against Muhammad

The Makhzum clan strongly opposed Muhammad. Their leader, Amr ibn Hisham (also known as Abu Jahl), was Khalid's cousin. He organized a boycott against Muhammad's clan. After Muhammad moved from Mecca to Medina in 622, the Makhzum clan fought against him. They were defeated at the Battle of Badr in 624. Many of Khalid's relatives, including Abu Jahl, died in that battle.

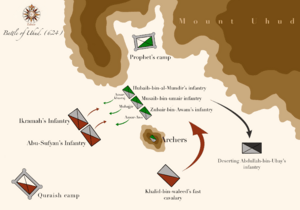

The next year, Khalid led the cavalry on the right side of the Meccan army. They faced Muhammad's forces at the Battle of Uhud, north of Medina. Instead of attacking head-on, Khalid smartly went around the mountain. He bypassed the Muslim forces. The Muslims first gained an advantage. But when many Muslim archers left their positions, Khalid attacked their weak rear lines. This led to a Muslim defeat, and many were killed. Khalid rode through the battlefield, fighting Muslims with his lance. Historians credit Khalid's "military genius" for the Quraysh's victory at Uhud. This was the only time the Quraysh defeated Muhammad.

In 628, Muhammad and his followers went to Mecca for a pilgrimage. The Quraysh sent 200 cavalry, led by Khalid, to stop them. Muhammad avoided Khalid by taking a difficult, unusual route. He reached Hudaybiyya, near Mecca. When Khalid realized Muhammad had changed course, he returned to Mecca. A truce was then made between the Muslims and the Quraysh. This was called the Treaty of Hudaybiyya.

Becoming a Muslim and Serving Muhammad

Around 627 or 629, Khalid became a Muslim. He did this in Muhammad's presence, along with another Qurayshite named Amr ibn al-As. After becoming Muslim, Khalid used all his great military skills to support the new Muslim state.

In September 629, Khalid took part in the Battle of Mu'tah in modern-day Jordan. The Muslim army was defeated by Byzantine forces. Several Muslim commanders were killed. Khalid then took command of the army. He managed to lead a safe retreat for the Muslims, which was very difficult. Muhammad rewarded Khalid by giving him the special title "Sayf Allah" ('the Sword of God').

In late 629 or early 630, Khalid helped Muhammad capture Mecca. After this, most of the Quraysh tribe became Muslim. Khalid led a group of Bedouin fighters into the city. In the fighting, three of his men were killed, and twelve Qurayshites died. Khalid also led the Muslim advance guard at the Battle of Hunayn later that year. In this battle, the Muslims defeated the Thaqif and Hawazin tribes. Khalid was then ordered to destroy the idol of al-Uzza, a goddess worshipped before Islam.

Later in 630, Muhammad sent Khalid to capture the town of Dumat al-Jandal. Khalid made the town surrender and imposed a heavy payment on its people. In June 631, Khalid was sent by Muhammad with 480 men to invite the Christian and polytheistic Balharith tribe to become Muslim. The tribe converted, and Khalid taught them about the Qur'an and Islamic laws.

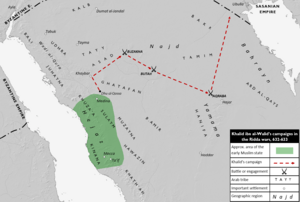

Leading in the Ridda Wars

After Muhammad died in June 632, Abu Bakr became the new leader, or caliph, of the Muslim community. Many tribes in Arabia stopped supporting the new Muslim state. Some had never formally joined Medina. Islamic history calls Abu Bakr's efforts to bring these tribes back under Muslim rule the Ridda wars. These were wars against tribes who challenged the new Muslim state.

Abu Bakr sent Khalid to fight against these rebel tribes in central Arabia. Khalid led his forces, made up of early Muslims who had moved from Mecca and those who lived in Medina. During these campaigns, Khalid showed great independence. He often made his own decisions, not always strictly following the caliph's orders. He simply defeated anyone who stood in his way.

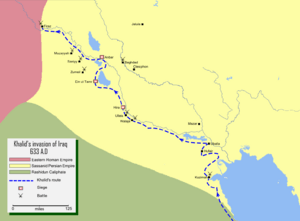

Campaigns in Iraq

After bringing peace to the Yamama region, Khalid marched north towards Persian territory in Iraq. He reorganized his army. He arrived at the southern Iraqi border with about 1,000 warriors in 633.

Khalid focused his attacks on the western banks of the Euphrates river. He fought against small Persian garrisons guarding the border. He had battles at places like Dhat al-Salasil, Nahr al-Mar'a, Madhar, Ullays, and Walaja. These last two places were near al-Hirah, an Arab market town and a Persian administrative center.

Capturing Al-Hira was Khalid's most important gain in this campaign. After defeating the city's Persian cavalry, Khalid and part of his army entered the city. The Arab nobles of Al-Hira, many of whom were Christians, barricaded themselves in their palaces. Khalid's other forces attacked villages around Al-Hira. Many of these villages were captured or agreed to pay tribute to the Muslims. The nobles of Al-Hira surrendered. They agreed to pay a yearly tribute in exchange for their churches and palaces being left alone. This was the first tribute the Caliphate received from Iraq.

Khalid continued north along the Euphrates valley. He attacked Anbar and then moved against Ayn al-Tamr, an oasis town. He faced strong resistance there. Khalid had to besiege the town's fortress. After defeating the defenders, Khalid captured the town. By this point, Khalid had brought the western areas of the lower Euphrates and many nomadic tribes under Muslim control.

March to Syria

All early Islamic accounts agree that Abu Bakr ordered Khalid to leave Iraq and go to Syria. He was to support the Muslim forces already fighting there. Khalid likely started his march to Syria in early April 634. He left small Muslim garrisons in the captured cities of Iraq.

Before marching to Syria, Khalid led two more important operations. One was against Dumat al-Jandal, and the other was against the Namir and Taghlib tribes. These tribes lived along the western banks of the upper Euphrates valley. These efforts aimed to bring the nomadic Arab tribes of northern Arabia and the Syrian steppe under Medina's control.

In the Dumat al-Jandal campaign, Khalid was asked to help another Muslim commander who was struggling to besiege the oasis town. The town's defenders were supported by their nomadic allies, who were allied with the Byzantine Empire. Khalid's combined Muslim forces defeated the defenders in a big battle.

Conquest of Syria

Most traditional stories say that the first Muslim armies went to Syria in early 634. The main commanders were Amr ibn al-As, Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, Shurahbil ibn Hasana, and Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah. By the time Khalid left Iraq, the Muslim armies in Syria had already fought some small battles. They controlled the southern Syrian countryside but not any major cities.

Khalid was made the supreme commander of the Muslim armies in Syria. Accounts say that Abu Bakr appointed Khalid because of his great military skills and past successes. Khalid arrived at the meadow of Marj Rahit north of Damascus on April 24, 634. There, Khalid attacked a group of Ghassanids. After this, Khalid and the other Muslim commanders gathered at Bosra, southeast of Damascus. Bosra was an important trading center. It surrendered in late May 634, becoming the first major city in Syria to fall to the Muslims.

Khalid and the Muslim commanders then went west to Palestine. They joined Amr for the Battle of Ajnadayn in July. This was the first major battle against the Byzantines. The Muslims won a decisive victory. The Byzantines retreated towards Pella. The Muslims followed them and won another big victory at the Battle of Fahl.

Death and Legacy

Less than four years after he was removed from military command, Khalid died in 642. He was buried in Emesa, where he had lived since his dismissal. His tomb is now part of a mosque called Khalid ibn al-Walid Mosque. Khalid's tombstone lists over 50 battles he commanded without a single defeat.

It is said that Khalid wanted to die as a martyr on the battlefield. He was reportedly disappointed when he realized he would die in his bed.

Khalid is remembered as a very effective commander of the early Muslim conquests. Historians call him "one of the tactical geniuses of the early Islamic period." He is known as "the most famous of all Arab Muslim generals." He was a brilliant and strong military leader. His reputation as a great general has lasted for generations. Streets are named after him all over the Arab world.

Images for kids

-

Illustration of the Battle of Yarmouk by an anonymous Catalan illustrator (c. 1310–1325).

See also

In Spanish: Jálid ibn al-Walid para niños

In Spanish: Jálid ibn al-Walid para niños