Byzantine army facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Byzantine army |

|

|---|---|

Imperial flag (basilikon phlamoulon) of the Palaiologan era (14th century)

|

|

| Leaders | Byzantine Emperor (commander-in-chief) |

| Dates of operation | c. 395–1453 |

| Headquarters | Constantinople |

| Active regions | Balkans, Asia Minor, Levant, Mesopotamia, Italy, Armenia, North Africa, Spania, Caucasus, Crimea |

| Part of | Byzantine Empire |

| Allies | Huns, Lombards, Armenians, Georgians, Serbs, Croats, Principality of Arbanon (Albanians), Crusader states, Anatolian beyliks, Khazars, Axum, Avars, Rus', Magyars, Heruli and others (intermittently) |

| Opponents | Goths, Huns, Sassanid Persia, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Avars, Slavs, Muslim Caliphate, Bulgaria, Rus', Normans, Albanians under House of Anjou-Durazzo, Armenians, Crusader states, Seljuks, Anatolian beyliks, Ottomans and others (intermittently) |

|

|

|

The Byzantine army was the main fighting force of the Byzantine Empire. It worked closely with the Byzantine navy. This army was a direct continuation of the Eastern Roman army. It kept a high level of discipline and organization, much like the ancient Hellenistic armies. For a long time in the Middle Ages, it was one of the most powerful armies in Western Eurasia.

Over time, cavalry became more important in the Byzantine army. The old legion system faded away by the early 7th century. The army also used many mercenary soldiers. These included Huns, Cumans, Alans, and later Turks. They often filled the need for light cavalry. Heavy infantry was often recruited from Frankish and later Varangian mercenaries.

From the 7th to the 12th centuries, the Byzantine army was incredibly strong. No other army in Middle Ages Europe or the Caliphate could match its strategies. In the 7th to mid-9th centuries, the Byzantines mostly played defense. They created the theme-system to fight the powerful Caliphate.

But from the mid-9th century, they started to attack more. This led to big conquests in the 10th century. Famous soldier-emperors like Nikephoros II Phokas, John Tzimiskes, and Basil II led these campaigns. The army they commanded was more professional. It had strong, well-trained infantry and powerful heavy cavalry. The Empire had one of the strongest economies in the world. This allowed them to raise large armies to reclaim lost lands.

After the theme-system weakened in the 11th century, the Byzantines relied more on professional Tagmata troops. They also used more foreign mercenaries. The Komnenian emperors tried hard to rebuild a native army. They started the pronoia system. This gave land to soldiers in exchange for military service. However, mercenaries remained important. The loss of Asia Minor meant fewer local recruits. The pronoia system also led to a kind of feudalism in the Empire. The successes of the Komnenian period ended with the Angeloi dynasty. This led to the Empire's fall to the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

The Emperors of Nicaea built a small but effective army. It used both native and foreign troops. This army successfully defended Byzantine lands in Anatolia. It also helped reclaim much of the Balkans and even Constantinople in 1261. However, the military was neglected again under Andronikos II Palaiologos. This allowed the Ottoman Empire to grow strong in Anatolia. Civil wars in the 14th century further weakened the Empire. The Byzantine army became a mix of local militias, personal guards, and mercenaries.

Contents

History of the Byzantine Army

The Byzantine Empire was actually a continuation of the Roman Empire. So, the Byzantine army grew out of the Late Roman military structure. This structure largely stayed the same until the mid-7th century. For centuries, the army's official language was Latin. But eventually, Greek became more common, like in the rest of the Empire. Still, some Latin military words were used throughout its history.

After the Muslim conquests, Syria and Egypt were lost. The remaining armies moved to Asia Minor. This started the thematic system. Even with this big disaster, the army's basic structure stayed similar. Tactics and training from the 6th to 11th centuries showed remarkable continuity. The Battle of Manzikert in 1071 and later Seljuk invasions severely weakened the Byzantine military. The arrival of the Crusades and Normans also hurt it. The Empire had to rely more and more on foreign mercenaries.

Early Army Changes

The Eastern Empire began when Emperor Diocletian created the Tetrarchy in 293 AD. His army changes lasted for centuries. Instead of traditional infantry-heavy legions, Diocletian split the army. He created limitanei (border guards) and comitatenses (field armies). The last legion, Legio V Macedonica, fought until the 7th or 8th centuries. It was destroyed fighting the Arabs.

Cavalry became more important, but infantry was still the largest part of the Roman armies. For example, in 533–534 AD, an army had 10,000 foot soldiers and 5,000 mounted archers and lancers.

The limitanei guarded the Roman borders (limes). Field units stayed behind the border. They could move quickly for attacks or defense. These field units had higher standards and better pay.

Cavalry made up about a quarter of the Roman armies. About half of the cavalry were heavy cavalry. They used spears or lances and swords. Some had bows to support charges. About 15% of the field armies were cataphractarii or clibanarii. These were heavily armored cavalry who used powerful charges. Light cavalry, including horse archers, were useful for patrols.

The comitatenses infantry were organized into regiments of 500–1,200 men. They were still heavy infantry with spears or swords, shields, armor, and helmets. Each regiment had light infantry skirmishers.

The Scholae Palatinae units were the Emperor's personal guard. They replaced the Praetorian Guard that Constantine I disbanded.

After Emperor Diocletian's changes (284–305 AD), legions were smaller, about 1,000 men. These units became static garrison troops. They sometimes served part-time as hereditary limitanei. They were separate from the new mobile field army.

Justinian I's Army

The army of Emperor Justinian I (527-565 AD) changed to meet new threats, especially from Persia. The old Roman legions were gone. Instead, there were smaller Greek infantry battalions or horse regiments called arithmos, tagma, or numerus. A numerus had 300 to 400 men. Two or more numeri formed a brigade (moira). Two or more brigades formed a division (meros).

There were six types of troops:

- The guard troops in the capital, Constantinople.

- The comitatenses (field army soldiers), also called stratiotai. They were recruited from the highlands of Thrace, Illyricum, and Isauria.

- The limitanei (border guards), also called akritai in Greek. They guarded frontiers and border posts. Their heroism led to folktales, like the hero Digenes Akritas.

- The foederati. These were barbarian volunteers who formed cavalry units.

- Allies. These were groups of barbarians like Huns or Goths. They provided military units in exchange for land or money.

- The bucellarii. These were private armed guards of generals and rich people. They were often a big part of a field army's cavalry.

Justinian's army was estimated to be between 300,000 and 350,000 soldiers. Field armies usually had 15,000 to 25,000 soldiers. They were mostly comitatenses and foederati, plus private guards and allies. For example, in 533, Belisarius's force to retake Carthage had less than 16,000 men.

The Byzantines copied Persian armor. They used mail coats, cuirasses, helmets, and steel leg guards. Elite heavy cavalrymen called cataphracts wore this armor. They used bows, swords, and lances. Many light infantry used bows to support the heavy infantry called scutatii (shield men). These wore steel helmets and mail coats. They carried spears, axes, and daggers.

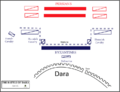

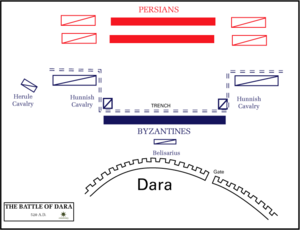

Famous battles during Justinian's reign include the Battle of Dara in 530. Belisarius defeated a much larger Persian army there. Belisarius also recaptured Sicily, Naples, and Rome from the Goths. Another famous general was Narses, who defeated a Gothic army in Italy in 552.

Towards the end of the 6th century, Emperor Maurice wrote The Strategikon. This was a manual for commanders. It described the Byzantine army, including equipment from former enemies like the Avars. Cavalrymen wore long mail coats and helmets. They had bows, lances, and swords. Horses had iron armor on their heads and chests.

The manual also described infantry. They wore Gothic tunics and shoes. Heavy infantry had shields of the same color, swords, lances, and helmets. They also used slings and lead-pointed darts. Light infantry carried bows with many arrows. They also had small shields and crossbows.

The Byzantine army and navy in 565 had about 379,300 men. This included field armies, guards, frontier troops, and oarsmen. These numbers likely stayed similar under Maurice.

Middle Byzantine Period (7th–11th Centuries)

The Themata System

The themata were new administrative areas of the empire. A general (strategos) controlled both civilian and military matters in each theme. The name thema likely meant "emplacements." Modern historians believe the first themes came from field armies stationed in Asia Minor.

The themes were created because the empire lost huge amounts of land and soldiers. This happened during the Muslim conquests in the 7th century. The empire's population dropped significantly. The size of its armed forces also fell sharply.

By 662, the empire had lost more than half its land in 30 years. The first themes appeared, led by generals. These were remnants of the old mobile armies, now settled in specific districts. Later, when cash payments were hard, soldiers received land grants in their districts. This helped support them.

The themes protected the empire from Arab invasions and raids until the late 11th century. Themes were also formed in the west to fight Serb and Bulgar attacks.

The five original themes were all in Asia Minor:

- The Armeniac Theme: Successor of the Army of Armenia. Its capital was Amasea.

- The Anatolic Theme: Successor of the Army of the East. Its capital was Amorium.

- The Opsician Theme: Where the imperial retinue (Obsequium) was based. Its commander was a komēs ("count").

- The Thracesian Theme: Successor of the Army of Thrace. Its capital was Ephesos.

- The corps of the Carabisiani: A naval corps based at Attaleia. It was later replaced by the Cibyrrhaeot Theme.

Within each theme, men received land to support their families and equip themselves. To prevent powerful revolts, emperors like Leo III the Isaurian split themes into smaller areas. They also divided control of the armies. In the 10th century, new, smaller themes were created in conquered eastern lands.

By 840, the empire's population had grown. The army expanded to 154,600 soldiers. This included 96,000 soldiers and marines in 20 themes.

Under the thematic generals, tourmarchai commanded divisions called tourmai. Below them, droungarioi led subdivisions called droungoi, each with a thousand soldiers. These units were further divided into banda with about 300 men.

| Name | No. of personnel | No. of subordinate units | Officer in command |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thema | 9 600 | 4 Tourmai | Strategos |

| Tourma | 2 400 | 6 Droungoi | Tourmarches |

| Droungos | 400 | 2 Banda | Droungarios |

| Bandon | 200 | 2 Kentarchiai | Komes |

| Kentarchia | 100 | 10 Kontoubernia | Kentarches/Hekatontarches |

| 50 | 5 Kontoubernia | Pentekontarches | |

| Kontoubernion | 10 | 1 "Vanguard" + 1 "Rear Guard" | Dekarchos |

| "Vanguard" | 5 | n/a | Pentarches |

| "Rear Guard" | 4 | n/a | Tetrarches |

Imperial Tagmata

The tagmata were the Empire's professional standing army. Emperor Constantine V formed them after a revolt in 741–743. He wanted loyal troops to protect his throne from rebellious thematic armies. These regiments were usually based in or near Constantinople. They were mainly heavy cavalry and formed the core of the imperial army on campaigns.

The four main tagmata were:

- The Scholai ("the Schools"): The oldest unit, a successor of the imperial guards.

- The Exkoubitoi ("the Sentinels"): Established by Leo I.

- The Arithmos ("Number") or Vigla ("Watch"): Guarded the Sacred Palace and Hippodrome in Constantinople. They also guarded the imperial camp and prisoners during campaigns.

- The Hikanatoi ("the Able Ones"): Established by Emperor Nicephorus I in 810.

There were also auxiliary tagmata. The Noumeroi were a garrison unit for Constantinople. They included the "regiment of the Walls" that manned the Walls of Constantinople. The Optimatoi were a support unit for the army's baggage train.

Between 773 and 899, the main cavalry tagmata had 16,000 horsemen. The infantry units had 4,000 foot soldiers. The Optimates had 2,000 support troops, later increased to 4,000. In 870, Imperial Fleet Marines were founded, adding another 4,000. The total active force was 28,000.

The Hetaireia ("Companions") included various mercenary groups. They were divided into Greater, Middle, and Lesser Companionships.

Komnenian Dynasty Army

Building a Strong Army

In 1081, the Byzantine Empire was very small. It was surrounded by enemies and financially ruined by civil wars. But Emperors Alexios I Komnenos, John II Komnenos, and Manuel I Komnenos rebuilt the empire's power. They did this by creating a new army from scratch.

This new force was called the Komnenian army. It was professional and well-disciplined. It had strong guard units like the Varangian Guard and the Immortals (heavy cavalry). These were stationed in Constantinople. It also had soldiers from the provinces. These included cavalry from Macedonia, Thessaly, and Thrace.

Under John II, new Byzantine troops were recruited from the provinces. As Byzantine Asia Minor grew stronger, more soldiers came from those areas. Soldiers were also taken from defeated groups, like the Pechenegs (cavalry archers).

Native troops were organized into regular units in both Asian and European provinces. Komnenian armies often had allied soldiers from Antioch, Serbia, and Hungary. Still, about two-thirds of the army were Byzantine troops. Different types of units (archers, infantry, cavalry) worked together to support each other.

The Komnenian army was very effective. It was well-trained and well-equipped. It could fight campaigns in Egypt, Hungary, Italy, and Palestine. However, its biggest weakness was that it needed a strong emperor to lead it. While Alexios, John, and Manuel ruled (about 1081–1180), the Komnenian army kept the empire safe. But after 1180, strong leadership disappeared. This had terrible results for the Byzantine Empire.

Decline Under the Angeloi

In 1185, Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos was killed. This ended the Komnenos dynasty, which had provided strong military emperors for over a century. The new rulers were the Angeloi. They are known as one of the least successful dynasties on the Byzantine throne.

The Byzantine army was very centralized at this time. The emperor personally led his forces against enemies. Generals were closely controlled. Everyone in the state looked to Constantinople for orders and rewards.

However, the Angeloi emperors were inactive and unskilled. This quickly led to the collapse of Byzantine military power. They spent money on expensive buildings and gifts, emptying the treasury. They also allowed army officers to do as they pleased, leaving the Empire almost defenseless. This ruined the state's finances.

The empire's enemies quickly took advantage. In the east, the Turks invaded and took Byzantine land in Asia Minor. In the west, the Serbs and Hungarians broke away. In Bulgaria, heavy taxes led to the Vlach-Bulgarian Rebellion in 1185. This rebellion created the Second Bulgarian Empire. This new empire was on land vital for Byzantine security in the Balkans.

Kaloyan of Bulgaria took several important cities. The Angeloi wasted money on palaces and gardens. They tried to solve problems with diplomacy instead of military action. Byzantine authority became very weak. This power vacuum caused the empire to break apart. Provinces started to rely on local strongmen instead of the government in Constantinople. This further reduced the resources available to the empire and its military.

Armies of Later States and the Palaiologoi

After 1204, the emperors of Nicaea continued some parts of the Komnenian system. But even after the empire was restored in 1261, the Byzantines never had the same wealth, land, or manpower. As a result, the military always lacked funds. After Michael VIII Palaiologos died in 1282, unreliable mercenaries, like the large Catalan Company, made up a bigger part of the army.

At the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Byzantine army had about 7,000 men. About 2,000 of these were foreign mercenaries. They faced 80,000 Ottoman troops besieging the city. The odds were hopeless. The Byzantines fought off the third attack by the Sultan's elite Janissaries. Some accounts say they were close to pushing them back. But a general from Genoa, Giovanni Giustiniani, was badly wounded. His leaving the walls caused panic among the defenders. Many Italian soldiers, paid by Giustiniani, fled.

Some historians suggest the Kerkoporta gate was left unlocked. The Ottomans found this mistake. The Ottomans rushed in. Emperor Constantine XI himself led the city's last defense. He threw aside his royal robes and fought the oncoming Ottoman Turks with sword and shield.

The emperor was struck twice by Turkish troops. He died from a knife to his back. There, on the walls of Constantinople, alone, the emperor died. The fall of Constantinople meant the end of the Roman Empire. The Byzantine army, the last direct descendant of the Roman legions, was finished.

Army Size Over Time

The exact size of the Byzantine army is debated because old records are unclear. The table below shows approximate numbers. These numbers do not include oarsmen for the navy.

| Manpower | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Historians like Warren Treadgold believe the Middle Byzantine army was much larger than other European armies at the time.

Byzantine Troop Types

Cataphracts

The Byzantines created "cataphracts" to match the heavy cavalry of the Persians. The word cataphract means 'completely armored' in Greek. These were heavily armed and armored cavalrymen. Both the rider and the horse were heavily armored. Riders used lances, bows, and maces. These troops were slow but very effective in battle, especially under Emperor Nikephoros II. More heavily armored types were called clibanarii.

Cavalry

Byzantine cavalry were great for fighting on the plains of Anatolia and northern Syria. These areas were key battlegrounds against Muslim forces. They were heavily armed with lances, maces, and swords. They also used strong composite bows. This made them effective against faster, lighter enemies like Arabs, Turks, Hungarians, and Pechenegs.

By the mid-Byzantine period (around 900–1200), regular mounted troops were divided into:

- Katafraktoi: Heavily armored for shock attacks.

- Koursorses: Medium weight, with mail or scale armor.

- Lightly armed horse archers.

Infantry

The Byzantine Empire's military tradition came from the late Roman period. Its armies always included professional infantry soldiers. However, in the middle period, infantry became less important than cavalry. Cavalry was now the main attacking force.

Equipment varied, especially among theme infantry. An average infantryman of the middle period might have a large spear, sword or axe, plumbata (lead-weighted darts), a large oval or round shield, a metal helmet or thick felt cap, and quilted or leather armor. Richer soldiers might afford iron lamellar or chain mail. Byzantine infantry were not as heavily armored as earlier Greco-Roman soldiers. Their strength came from their excellent organization and discipline.

Pronoiars

Pronoiar troops appeared in the 12th century, especially under Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1143–1180). These soldiers were paid with land instead of money. This was different from the old theme system. Pronoiai became like a license to tax citizens living on the land grant. Pronoiars were like tax collectors who kept some of the money they collected.

These men are often seen as the Byzantine version of Western knights. They were part soldiers, part local rulers. However, the emperor still legally owned the Pronoiars' land. Pronoiars were usually cavalry. They would have worn mail armor, used lances, and had horse barding. Manuel re-equipped his heavy cavalry in a Western style. Many of these troops were likely pronoiars. These troops became very common after 1204, serving the Empire of Nicaea.

Akritoi

Akrites (plural Akritoi) were defenders of the Empire's Anatolian borders. They appeared after the Arab conquests or later when Turkish tribes raided Anatolia. Akritoi units were made of native Greeks living near the eastern borders. It's debated if they were soldier-farmers or lived on rents. Akritoi were probably mostly light troops, using bows and javelins.

They were skilled at defensive warfare, especially against raiding Turkish horsemen in the mountains. They could also cover the regular Byzantine army's advance. Their tactics likely involved skirmishing and ambushes. Greek folklore and traditional songs often feature Akrites and their heroic deeds.

Foreign and Mercenary Soldiers

The Byzantine army often hired foreign mercenary troops from many regions. These troops often helped the empire's regular forces. Sometimes, they even made up most of the Byzantine army. For much of the Byzantine army's history, foreign soldiers showed the wealth and power of the Byzantine empire. An emperor who could gather armies from all over the known world was truly formidable.

Foreign troops in the late Roman period were called foederati ("allies"). In the Byzantine period, they were known as Phoideratoi. Later, foreign troops (mostly mercenaries) were called Hetairoi ("Companionships"). They were often used in the Imperial Guard. This force was divided into Great, Middle, and Minor Companionships.

Barbarian Tribes

In the early 6th century, several barbarian tribes joined the armies of the Eastern Roman Empire. These included the Heruli, who had overthrown the last Western Roman Emperor. Other barbarians were the Huns and the Gepids.

Emperor Justinian used these barbarian mercenaries to help reclaim lost Roman lands in the West. These lands included Italy, North Africa, Sicily, and Gaul. The Byzantine general Belisarius used Hunnic archers and Heruli mercenaries to retake North Africa. He also used Heruli infantry and Hunnic horsemen to secure Sicily and southern Italy.

In 552, the general Narses defeated the Ostrogoths with an army that included many Germanic soldiers. Two years later, Narses crushed a combined army of Franks and Alemanni with Roman and Heruli mercenary troops.

During the Komnenian period, mercenary units were often named by their ethnicity. Examples include the Inglinoi (Englishmen), Phragkoi (Franks), and Skythikoi (Scythians). Even Ethiopians served under Emperor Theophilos. These mercenary units, especially the Skythikoi, were also used as a police force in Constantinople.

Varangian Guard

The most famous Byzantine regiment was the legendary Varangian Guard. This unit started in 988 with 6,000 Rus sent to Emperor Basil II by Vladimir of Kiev. These axe-wielding Northerners were excellent fighters and very loyal (for a price). They became an elite personal bodyguard for the Emperors. Their commander was called Akolouthos ("Acolyte/follower" to the Emperor).

At first, most Varangians were from Scandinavia. But later, the guard included many Anglo-Saxons after the Norman Conquest of England. The Varangian Guard fought bravely at the Battle of Beroia in 1122. They were also at the Battle of Sirmium in 1167, where the Byzantine army defeated the Kingdom of Hungary. The Varangian Guard is thought to have been disbanded after Constantinople was sacked by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Many accounts agree they were the most important Byzantine unit and helped fight off the first Crusader attacks.

Byzantine Weapons

Handheld Weapons

The Byzantines first used weapons from their Late Roman past. These included the longsword (spatha), lance (contus), javelins, the lead-weighted dart (plumbata), sling, and the recurve composite bow. As military technology changed, the Byzantines adapted. They adopted new bow designs from the Avars, Magyars, and Seljuk Turks. They also changed their infantry tactics and equipment.

There were many types of sword (spathion). They could be straight, curved, one-handed, or two-handed. By the 5th century, the short Roman gladius was replaced by the long, two-edged spatha. The 10th-century Sylloge Tacticorum mentions a new saber-like sword called the paramerion. This was a curved, one-edged slashing weapon for cavalry.

Pikes and lances (kontaria) in the 10th century were about 4 meters long with an iron point. One type of infantry spear, the menaulion, was very thick. It was 1.9 to 3.1 meters long with a large head. It was used by medium infantrymen against enemy kataphraktoi. Both light infantry and cavalry carried javelins (akontia) no longer than two meters.

Maces (rabdion) and axes (pelekion) were used for shock attacks. The 10th-century kataphraktoi carried heavy iron maces to hit enemy soldiers through their armor. Double-headed and single-headed battle axes are mentioned. The Varangian Guard famously used Dane axes.

The sling or staff sling (sphendobolos), javelin (akontion), and bow (toxarion) were used by infantry, skirmishers, and archers. The Byzantine bow was a composite, recurve type. The solenarion was a hollow tube that could launch several small darts quickly. Anna Komnene noted that the Western-style crossbow (tzangra) was new to Byzantium in the 12th century. Crossbows were adopted by Byzantine infantry in the 13th century, mainly for naval combat and sieges.

Shields

The shield (skoutarion) came in several forms. Large oval and circular shields were common. Later, smaller circular shields and oblong kite shields (thyreos) became popular around 900 AD. The Tactica of Leo VI states that shield patterns and tunic colors matched the regiment. Most shield designs were geometric patterns. Crosses appeared on shields starting in the 12th century. Proto-heraldic patterns, like lions, also appeared by the 12th–13th century.

Armor

Armor was well-documented in late antiquity. Lamellar armor (kelivanon) was introduced around 520 AD. Many lamellar cuirasses have been found from late Roman sites. Maille (lorica hamata) and scale (lorica plumata) armor are also seen in artwork. Fragments of maille armor have been found. Full mail hauberks are known from the 6th century.

Limb armor was also used. The Strategikon mentions kheiromanika sidera ("iron hand-sleeves") and ocreae (greaves). Helmets from the 6th–8th centuries are well-documented. These include lamellar helmets, band helmets, and spangenhelms. Later, the medieval conical helmet became more popular.

Scale, Maille, and Lamellar armor are all seen in Byzantine artwork from the 6th–14th centuries. Defensive cloth armor was also used. Skirts attached to armor were called kremasmata. They could be made of maille, cloth, scale, or lamellar. Pauldrons (shoulder armor) and arm and leg armor were also used.

Artillery

The Traction Trebuchet likely came from China to Europe around 550–580 AD. The late Roman army quickly adopted it, calling it a manganikon. Counterweight trebuchets are thought to have been invented in the middle Byzantine period. Anna Komnene says new artillery was invented by Alexios Komnenos in 1097. Counterweight trebuchets are described shortly after, from the 1120s onwards.

The Tactica of Leo VI also mentions the toxobolistra. This was an iron-framed torsion engine. Finally, the siphon and kheirosiphon were used to project Greek fire from warships and walls.

Byzantine Military Philosophy

Unlike the Roman legions, the Byzantine army's strength was in its armored cavalry Cataphracts. These evolved from the Clibanarii of the late empire. Their warfare and tactics came from Hellenistic military manuals. Infantry were still used, but mainly to support the cavalry.

According to David Nicolle, morale was very important. Byzantine leaders paid close attention to it. Byzantium's role as the Christian Empire was central to its morale. Careful religious preparations happened before a battle. This included parading crosses, relics, and images. These things had a deep impact on the soldiers' minds.

Major Battles of the Byzantine Empire

Early Byzantine Period

- Battle of Thannuris

- Battle of Dara

- Battle of Callinicum (531)

- Battle of Tricamarum (533)

- Siege of Rome (537-538)

- Battle of Taginae (552)

- Battle of Nineveh (627)

- Battle of Mu'tah (629)

- Battle of Firaz (634)

- Battle of Ajnadayn (634)

- Battle of Fahl (635)

- Battle of Yarmouk (636)

- Battle of the Iron Bridge (637)

- Battle of Ongal (680)

- Battle of Carthage (698)

- Siege of Constantinople (717–718)

Middle Byzantine Period

- Battle of Pliska (811)

- Battle of Versinikia

- Battle of Boulgarophygon (896)

- Battle of Achelous (917) (917)

- Siege of Chandax

- Sack of Aleppo (962)

- Battle of Arcadiopolis (970)

- Siege of Dorostolon

- Battle of the Gates of Trajan

- Battle of Kleidion (1014)

- Battle of Manzikert (1071)

- Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081)

- Battle of Kalavrye

- Battle of Levounion (1091)

- Siege of Nicaea (1097)

- Battle of Dorylaeum (1097)

- Battle of Beroia (1122)

- Battle of Sirmium (1167)

- Battle of Myriokephalon (1176)

- Battle of Arcadiopolis (1194)

Late Byzantine Period

- Siege of Constantinople (1203)

- Sack of Constantinople

- Battle of Antioch on the Meander (1211)

- Battle of Klokotnitsa

- Battle of Pelagonia (1259)

- Reconquest of Constantinople

- Battle of Bapheus

- Siege of Bursa

- Battle of Pelekanon (1329)

- Fall of Constantinople (1453)

- Siege of Trebizond (1461)

Images for kids

-

Emperor Constantine I

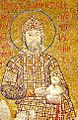

-

Emperor John II Komnenos became renowned for his superb generalship and conducted many successful sieges. Under his leadership, the Byzantine army reconquered substantial territories from the Turks.

-

Map of the Byzantine Empire in c. 1270. After the damage caused by the collapse of the theme system, the mismanagement of the Angeloi and the catastrophe of the Fourth Crusade, for which the Angeloi were largely to blame, it proved impossible to restore the empire to the position it had held under Manuel Komnenos.

-

The deployment of the armies in the Battle of Dara (530), in which Byzantium employed various foreign mercenary soldiers, including the Huns.

-

Coin of emperor Basil II, founder of the Varangian Guard.

-

Byzantine fresco of Joshua from the Hosios Loukas monastery, 12th to 13th century. A good view of the construction of the lamellar klivanion cuirass. Unusually, the Biblical figure is shown wearing headgear; the helmet and its attached neck and throat defences appear to be cloth-covered. Joshua is shown wearing a straight spathion sword.

-

A Byzantine fresco of Saint Mercurius with a sword and helmet, dated 1295, from Ohrid, North Macedonia

-

This image by Gustave Doré shows the Turkish ambush at the battle of Myriokephalon (1176)

See also

In Spanish: Ejército bizantino para niños

In Spanish: Ejército bizantino para niños

- Byzantine battle tactics

- Byzantine bureaucracy

- East Roman army

- Roman navy

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |