John II Komnenos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids John II Komnenos |

|

|---|---|

| Emperor and Autocrat of the Romans | |

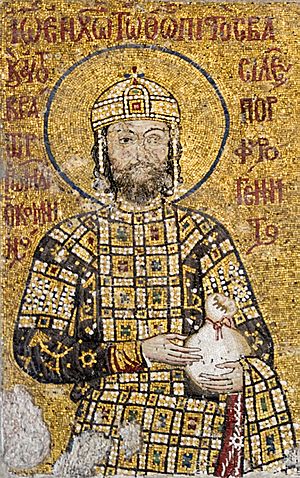

Mosaic of John II at the Hagia Sophia

|

|

| Byzantine emperor | |

| Reign | 15 August 1118 – 8 April 1143 |

| Coronation | 1092 as co-emperor |

| Predecessor | Alexios I Komnenos |

| Successor | Manuel I Komnenos |

| Co-emperor | Alexios the Younger |

| Born | 13 September 1087 Constantinople, Byzantine Empire (now Istanbul, Turkey) |

| Died | 8 April 1143 (aged 55) Cilicia, Byzantine Empire (now Southeastern Anatolia, Anatolia, Turkey) |

| Burial | Monastery of Christ Pantocrator, Constantinople (now Zeyrek Mosque, Istanbul) |

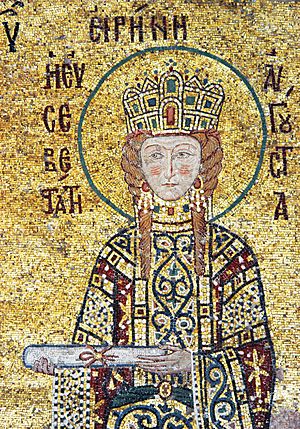

| Spouse | Irene of Hungary |

| Issue | Alexios the Younger Maria Komnene Andronikos Komnenos Anna Komnene Isaac Komnenos Theodora Komnene Eudokia Komnene Manuel I Komnenos |

| Dynasty | Komnenian |

| Father | Alexios I Komnenos |

| Mother | Irene Doukaina |

| Religion | Orthodox |

John II Komnenos (born September 13, 1087 – died April 8, 1143) was a Byzantine emperor who ruled from 1118 to 1143. He was also known as "John the Good" or "John the Beautiful" (Kaloïōannēs). He was the oldest son of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Irene Doukaina. John was the second emperor from the Komnenos dynasty to rule during a time when the Byzantine Empire was trying to regain its strength.

Because he was born while his father was already emperor, he had a special status called porphyrogennetos, meaning "born in the purple." John was a very religious and dedicated ruler. He wanted to fix the problems his empire faced after the Battle of Manzikert about 50 years earlier. Many historians consider John to be the greatest emperor of the Komnenos family.

During his 25-year reign, John made important alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the west. He also won major victories against the Pechenegs, Hungarians, and Serbs in the Balkans. He personally led many military campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor. John's campaigns changed the power balance in the east, forcing the Turks to defend themselves. He also recaptured many towns, forts, and cities across Anatolia. In the southeast, John expanded Byzantine control from the Maeander River to Cilicia and Tarsus.

John wanted to show that the Byzantine emperor was the leader of the Christian world. So, he marched into Muslim Syria with his army and forces from the Crusader states. Even though he fought bravely, his hopes were not fully met. His Crusader allies were not very helpful and did not want to fight alongside his troops. Under John's rule, the empire's population grew to about 10 million people.

Contents

John's Appearance and Character

The historian William of Tyre described John as short and not very handsome. He had dark eyes, hair, and skin, which led some to call him 'the Moor'. However, despite his looks, he was known as Kaloïōannēs, meaning "John the Good" or "John the Beautiful." This nickname referred to his kind and noble character.

Both of John's parents were very religious, and John was even more so. People at his court were expected to talk only about serious topics. The food served at the emperor's table was simple. John would even lecture courtiers who lived in too much luxury. He spoke with dignity but sometimes enjoyed a witty remark. Everyone agreed that he was a loyal husband to his wife, which was unusual for a ruler in those times. Even though he lived simply, John believed the emperor's role was very important. He would appear in grand ceremonial clothing when it was helpful.

John was famous for his strong faith and his remarkably fair and gentle rule. He is seen as an excellent example of a moral ruler, especially when cruelty was common. It is said that he never sentenced anyone to death. He gave generously to charity. For these reasons, some have called him the Byzantine Marcus Aurelius. His personal morality and faith helped improve the behavior of people in his time. Stories about him show that he had great self-control and courage. He was also an excellent military planner and general.

Becoming Emperor

John II became the ruling emperor after his father, Alexios I, died in 1118. However, Alexios I had already crowned John as co-emperor between September and November 1092. This meant John was meant to take over.

Even with this early crowning, John's claim to the throne was challenged. Alexios I's powerful wife, Irene, wanted her son-in-law, Nikephoros Bryennios, to be emperor. Nikephoros was married to her oldest daughter, Anna Komnene. Anna herself wanted power and the throne. While Alexios was very ill, his wife and daughter tried to pressure him to change who would be his successor. But Alexios never officially changed his mind.

On August 15, 1118, as Alexios was dying, John quickly acted. With the help of trusted relatives, especially his brother Isaac, John entered the monastery where his father was. He got the imperial ring from his father. Then, he gathered his armed followers and rode to the Great Palace. People in the city supported him along the way. The palace guards at first did not let John in without clear proof of his father's wishes. However, the crowd around the new emperor simply forced their way in. Inside the palace, John was declared emperor. Irene was surprised and could not convince her son to step down. She also could not get Nikephoros to fight for the throne.

Alexios died the night after John took power. John did not attend his father's funeral, even though his mother begged him. He feared a counter-attack. But within a few days, his position seemed safe. However, about a year later, John II discovered a plot to overthrow him. His mother and sister were involved. Anna's husband, Nikephoros, did not support her plans, which caused the plot to fail. Anna lost her property, which was offered to John's friend John Axouch. Axouch wisely refused, and his influence helped Anna get her property back. John II and his sister then became somewhat reconciled. Irene retired to a monastery, and Anna mostly left public life to become a historian. Nikephoros remained on good terms with John.

John took steps to secure his own succession. Around September 1119, he crowned his young son Alexios as co-emperor.

Running the Empire and the Army

The family problems that challenged John's rise to power likely influenced how he ruled. He chose to appoint people from outside the imperial family to important positions. This was a big change from his father's way of doing things. Alexios I had used his large family to fill almost all top government and military jobs.

John Axouch was John II's closest advisor and his only true friend. Axouch was a Turk who had been captured as a child and given as a gift to John's father. Emperor Alexios thought he would be a good companion for his son, so Axouch grew up with John in the imperial household. As soon as John II became emperor, Axouch was made Grand Domestic. This was the commander-in-chief of the Byzantine armies. It is also thought that Axouch was the head of the empire's civil government, like a 'prime minister'. This appointment was very unusual and a big change from the favoritism of Alexios I's reign. The imperial family was somewhat upset by this decision. They even had to bow to John Axouch whenever they met him.

John continued to keep his family from having too much influence in his government throughout his reign. He appointed some of his father's trusted servants to high administrative roles. These included men like Eustathios Kamytzes, Michaelitzes Styppeiotes, and George Dekanos. These men had lost influence when John's mother was powerful during Alexios I's later years. John II also promoted new people, such as Gregory Taronites, who became a chief official. Manuel Anemas and Theodore Vatatzes also rose to importance and later married John's daughters. John's marriage policy, which brought new families into the imperial circle, might have been aimed at reducing the power of certain noble families. These included the Doukas, Diogenes, and Melissenos families, some of whom had produced emperors in the past.

Even though John moved away from relying heavily on his family, his court and government were similar to his father's. They both had a serious and religious atmosphere. There is even a collection of political advice written in poetry, called the Mousai, which is believed to be from Alexios I. The Mousai are directly addressed to John II. They tell him, among other things, to be fair and keep the treasury full. So, Alexios's advice on ruling was still available to his son even after the old emperor died.

John II's military campaigns brought more safety and economic stability to western Anatolia. This allowed him to start setting up a formal provincial system in these areas. The province of Thrakesion was re-established, with its main city at Philadelphia. A new province, called Mylasa and Melanoudion, was created south of Thrakesion.

Family Challenges: Isaac's Plots

John II's younger brother, Isaac, had been a great help when John became emperor. However, even though Isaac was given the highest court title, sebastokrator, he later became distant from his brother and started plotting against him. John II, with his trusted advisors like John Axouch and later his son Alexios, did not give Isaac a meaningful role in running the empire. During Alexios I's reign, sebastokratores had a lot of power, and Isaac likely expected the same. This frustrated ambition probably made Isaac unhappy with his brother's rule. Isaac wanted to replace his brother as emperor.

In 1130, John learned about a plot involving Isaac and other nobles as he was leaving to fight the Turks. When John tried to capture Isaac, Isaac escaped. He fled to the Danishmend emir Ghazi, who welcomed him. Later, Ghazi sent him to the breakaway Byzantine rulers, the Gabrades, in Trebizond. Isaac then stayed with Masoud, the Seljuk Sultan of Rum, and later with Leo, the Prince of Cilician Armenia. It is very likely that Isaac was seeking help from these rulers to take the Byzantine throne by force. This alliance did not happen, but Isaac seemed to have strong support in Constantinople.

In 1132, John had to rush back from a campaign. News reached him that plotters in Constantinople had asked Isaac to become their ruler. The victory celebration John held after capturing Kastamuni in 1133 showed the public that John was the rightful emperor. This was celebrated by showing the defeat of outside enemies. The brothers were briefly friends again in 1138, and Isaac returned to Constantinople. However, a year later, Isaac was sent away to Heraclea Pontica, where he stayed for the rest of John's life. In the many artworks Isaac ordered, he often highlighted his porphyrogenete status (born in the purple) and his connection to his father, Alexios I. But he rarely mentioned his brother John or the title of sebastokrator that John had given him.

Working with Other Countries

John II's main foreign policy goal in the West was to keep an alliance with the German emperors (Holy Roman Empire). This was important to limit the threat from the Normans of southern Italy to Byzantine lands in the Balkans. This threat became very serious after Roger II of Sicily became powerful in southern Italy and took the title of king. Emperor Lothair III had Byzantine support, including a large amount of money, for his invasion of Norman territory in 1136. This invasion reached as far south as Bari. Pope Innocent II, whose Church's lands in Italy were threatened by Roger II, also joined the alliance with Lothair and John II. However, this alliance could not stop Roger. He forced the Pope to recognize his royal title in 1139 (Treaty of Mignano).

Lothair's successor, Conrad III, was asked in 1140 for a German royal bride for John's youngest son, Manuel. Bertha of Sulzbach, Conrad's sister-in-law, was chosen and sent to Byzantium. Around the same time, Roger II asked John II for an imperial bride for his son, but he was not successful.

John's habit of getting involved with his wife's family, the rulers of Hungary, caused problems. The Byzantines saw welcoming ousted Hungarian throne claimants in Constantinople as a useful way to gain political influence. However, the Hungarians saw this interference as a reason to fight. A Hungarian alliance with the Serbs caused serious issues for continued Byzantine control in the western Balkans.

In the East, John tried, like his father, to use the disagreements between the Seljuq Sultan of Iconium and the Danishmendid dynasty. The Danishmends controlled the northeastern, inland parts of Anatolia. In 1134, the Seljuq sultan Masoud provided troops for John's attack on the Danishmend city of Kastamuni. However, this alliance was not reliable, as the Seljuq troops left the expedition during the night.

In the Crusader states of the Levant, it was generally agreed that the Byzantine claims over Antioch were legally correct. But in reality, they were only recognized when the Byzantine emperor could enforce them with military power. A high point of John's diplomacy in the Levant was in 1137. He received formal loyalty from the rulers of the Principality of Antioch, County of Edessa, and the County of Tripoli. The Byzantine desire to be seen as having power over all the Crusader states was taken seriously. This was shown by the alarm in the Kingdom of Jerusalem when John told King Fulk about his plan for an armed pilgrimage to the Holy City in 1142.

Religious Matters

John II's reign was almost always filled with war. Unlike his father, who enjoyed taking part in religious debates, John seemed happy to let the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and the church leaders handle church matters. John only became actively involved when religion directly affected imperial policy, such as relations with the Pope and the possible joining of the Greek and Latin churches. He organized several discussions between Greek and Latin religious thinkers.

John, along with his wife who shared his religious and charitable work, built many churches. This included the Monastery of Christ Pantokrator (Zeyrek Mosque) in Constantinople. This monastery, with its three churches, is considered one of the most important and influential buildings of the Middle Byzantine period in Constantinople. A hospital with five wards was attached to the monastery. It was open to people of all social classes. The hospital was staffed by trained non-monk doctors. The central of the three churches was the Komnenian family's burial chapel, dedicated to St. Michael. It had two domes and was described as a hero's tomb, similar to the older tombs of Constantine and Justinian in the Church of the Holy Apostles.

In the last few years of Alexios I's reign, there was active persecution of followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies. There are no records from John's reign that mention such persecution, though the Byzantine Church continued to take action against heresy. A permanent church council in Constantinople investigated the writings of a deceased monk named Constantine Chrysomallos. These works had been circulating in some monasteries. The Patriarch of Constantinople, Leo Styppes, ordered these works to be burned in May 1140. This was because they contained parts of Bogomil beliefs and practices.

One of the few family members John placed in an important position was his cousin, Adrian Komnenos. Adrian had become a monk and adopted the name John. He had joined the emperor on his campaigns in 1138. Soon after, Adrian was appointed Archbishop of Bulgaria as John IV of Ohrid. Bulgaria was an independent church, and it needed a respected man as archbishop.

Military Victories

John II fought several important battles. However, his military plan focused on capturing and holding fortified settlements to create strong borders. John personally led about 25 sieges during his reign.

Defeating the Pechenegs (1122)

In 1119–1121, John defeated the Seljuq Turks. This helped him gain control over southwestern Anatolia. But right after this, in 1122, John quickly moved his troops to Europe. He needed to stop a Pecheneg invasion across the Danube river into Paristrion. These invaders were allies of the Prince of Kiev.

John surrounded the Pechenegs as they entered Thrace. He tricked them into thinking he would offer them a good peace treaty. Then, he launched a sudden, powerful attack on their fortified camp. The Battle of Beroia that followed was tough. John was wounded in the leg by an arrow. But by the end of the day, the Byzantine army had won a huge victory. The key moment was when John led the Varangian Guard, who were mostly Englishmen, to attack the Pechenegs' wagon laager. They used their famous axes to break through. This battle effectively ended the Pechenegs as an independent people. Many of the captives were settled as soldier-farmers within the Byzantine borders.

Conflict with Venice (1124–1126)

After becoming emperor, John II refused to confirm a treaty his father made in 1082 with the Republic of Venice. This treaty had given Venice special and generous trading rights within the Byzantine Empire. However, John's change in policy was not mainly about money. An incident where Venetians mistreated a member of the imperial family led to a dangerous conflict. This was especially risky because Byzantium relied on Venice for its naval power.

After a Byzantine attack on Kerkyra in return, John sent Venetian merchants out of Constantinople. But this led to more retaliation. A Venetian fleet of 72 ships looted Rhodes, Chios, Samos, Lesbos, Andros, and captured Kefalonia in the Ionian Sea. Eventually, John had to make peace. The war was costing him too much, and he was not willing to move money from the army to the navy to build new ships. John re-confirmed the 1082 treaty in August 1126.

War with Hungary and Serbia (1127–1129)

John's marriage to the Hungarian princess Piroska involved him in the power struggles of the Kingdom of Hungary. By giving refuge to Álmos, a blind claimant to the Hungarian throne, John made the Hungarians suspicious. The Hungarians, led by Stephen II, then invaded Byzantium's Balkan provinces in 1127. The fighting lasted until 1129.

John launched a punishing raid against the Serbs, who had allied with Hungary. Many Serbs were captured and moved to Nicomedia in Asia Minor to become military settlers. This was done partly to force the Serbs to submit (Serbia was, at least in name, under Byzantine protection). It also helped strengthen the Byzantine border in the east against the Turks. The Serbs were forced to accept Byzantine rule again.

The Hungarian army attacked Belgrade, Nish, and Sofia. John, who was near Philippopolis in Thrace, counterattacked. He was supported by a naval fleet on the Danube river. After a difficult campaign, the emperor managed to defeat the Hungarians and their Serbian allies at the fortress of Haram. Many Hungarian soldiers died when a bridge they were crossing collapsed as they fled from a Byzantine attack. After this, the Hungarians attacked Braničevo again, which John immediately rebuilt. More Byzantine military successes led to peace. The Byzantines kept control of Braničevo, Belgrade, and Zemun. They also got back the region of Sirmium, which had been Hungarian since the 1060s. The Hungarian claimant Álmos died in 1129, removing the main cause of the conflict.

Fighting the Turks in Anatolia (1119–20, 1130–35, 1139–40)

Early in John's reign, the Turks were pushing against the Byzantine border in western Asia Minor. In 1119, the Seljuqs had cut off the land route to the city of Attaleia on the southern coast of Anatolia. John II and Axouch the Grand Domestic besieged and recaptured Laodicea in 1119. They also took Sozopolis by force in 1120. This re-opened land communication with Attaleia. This route was very important because it also led to Cilicia and the Crusader states in Syria.

After the war with Hungary ended, John could focus on Asia Minor for most of his remaining years. He led yearly campaigns against the Danishmendid emirate in Malatya (Melitene) on the upper Euphrates from 1130 to 1135. Thanks to his strong campaigns, Turkish attempts to expand in Asia Minor were stopped. John prepared to take the fight to the enemy. To bring the region back under Byzantine control, he led a series of well-planned and successful campaigns against the Turks. One of these led to the recapture of the Komnenoi family's original home at Kastamonu (Kastra Komnenon). He then left 2,000 soldiers at Gangra.

John quickly gained a strong reputation for breaking down walls, taking one stronghold after another from his enemies. Regions that had been lost to the empire since the Battle of Manzikert were recovered and guarded. However, resistance, especially from the Danishmends in the northeast, was strong. It was hard to hold onto the new conquests. For example, Kastamonu was recaptured by the Turks even while John was in Constantinople celebrating its return to Byzantine rule. But John kept fighting, and Kastamonu soon changed hands again.

In the spring of 1139, the emperor successfully campaigned against Turks, likely nomadic Turkomans. These groups were raiding areas along the Sangarios River. John hurt their ability to survive by driving away their herds. He then marched for the last time against the Danishmend Turks. His army traveled along the southern coast of the Black Sea through Bithynia and Paphlagonia. The breakaway Byzantine rule of Constantine Gabras in Trebizond ended, and the region of Chaldia came back under direct imperial control. John then besieged the city of Neocaesarea in 1140 but failed to capture it. The Byzantines were defeated by the harsh conditions rather than by the Turks. The weather was very bad, many army horses died, and food became scarce.

Campaigns in Cilicia and Syria (1137–1138)

In the Levant, the emperor wanted to strengthen Byzantine claims to power over the Crusader States and assert his rights over Antioch. In 1137, he conquered Tarsus, Adana, and Mopsuestia from the Principality of Armenian Cilicia. In 1138, Prince Levon I of Armenia and most of his family were taken as captives to Constantinople. This opened the way to the Principality of Antioch. There, Raymond of Poitiers, Prince of Antioch, and Joscelin II, Count of Edessa, recognized themselves as loyal to the emperor in 1137. Even Raymond II, the Count of Tripoli, quickly traveled north to show respect to John. He repeated the loyalty his predecessor had given John's father in 1109.

Then, there was a joint campaign as John led the armies of Byzantium, Antioch, and Edessa against Muslim Syria. Aleppo was too strong to attack. But the fortresses of Balat, Biza'a, Athareb, Maarat al-Numan, and Kafartab were captured by force.

Even though John fought hard for the Christian cause in Syria, his allies, Prince Raymond of Antioch and Count Joscelin II of Edessa, stayed in their camp playing dice and feasting. They did not help with the siege of the city of Shaizar. The Crusader Princes were suspicious of each other and of John. Neither wanted the other to gain from helping in the campaign. Raymond also wanted to keep Antioch, which he had agreed to hand over to John if the campaign successfully captured Aleppo, Shaizar, Homs, and Hama. Latin and Muslim sources describe John's energy and personal courage in leading the siege. The city was taken, but the citadel could not be captured. The Emir of Shaizar offered to pay a large sum of money, become John's loyal subject, and pay yearly tribute. John had lost all trust in his allies. Also, a Muslim army under Zengi was coming to try to help the city. So, the emperor reluctantly accepted the offer.

The emperor was distracted by a Seljuq raid on Cilicia and events in the west. There, he was working on a German alliance against the threat from the Normans of Sicily. Joscelin and Raymond secretly planned to delay handing over Antioch's citadel to the emperor. They stirred up public anger in the city against John and the local Greek community. John had little choice but to leave Syria with his goals only partly achieved.

Final Campaigns (1142)

In early 1142, John campaigned against the Seljuqs of Iconium to secure his communication lines through Attalia (Antalya). During this campaign, his oldest son and co-emperor Alexios died of a fever. After securing his route, John started a new expedition into Syria. He was determined to bring Antioch under direct imperial rule. This expedition also included a planned pilgrimage to Jerusalem, where he intended to take his army.

King Fulk of Jerusalem, fearing that the emperor's presence with a huge military force would make him pay homage and formally recognize Byzantine rule over his kingdom, begged the emperor to bring only a small escort. Fulk said that his mostly barren kingdom could not support a large army. This unenthusiastic response led John II to postpone his pilgrimage. John quickly moved into northern Syria, forcing Joscelin II of Edessa to give hostages, including his daughter, as a guarantee of his good behavior. He then advanced on Antioch, demanding that the city and its citadel be given to him. Raymond of Poitiers stalled for time, putting the proposal to a vote of Antioch's general assembly. As the season was late, John decided to take his army into winter camps in Cilicia. He planned to renew his attack on Antioch the following year.

Death and Who Came Next

After preparing his army for another attack on Antioch, John was hunting wild boar on Mount Taurus in Cilicia. He accidentally cut his hand with a poisoned arrow. John at first ignored the wound, and it became infected. He died a few days after the accident, on April 8, 1143, likely from a serious infection.

Some have suggested that John was killed by a plot within his army's Latin units. These soldiers were unhappy about fighting their fellow Christians in Antioch and wanted his pro-Western son Manuel to become emperor. However, there is very little direct evidence for this idea in the old writings.

John's last act as emperor was to choose Manuel, the younger of his surviving sons, to be his successor. John is recorded as giving two main reasons for choosing Manuel over his older brother Isaac: Isaac's bad temper, and the courage Manuel had shown during the campaign at Neocaesarea. Another idea is that the choice was based on a prophecy that said John's successor should have a name starting with "M." John's close friend John Axouch, even though he tried hard to convince the dying emperor that Isaac was a better choice, was key in making sure Manuel took power without major opposition.

John II's Legacy

Historian John Birkenmeier believed that John's reign was the most successful of the Komnenian period. In his book, The Development of the Komnenian Army 1081–1180, he highlights the wisdom of John's approach to warfare. John focused on sieges rather than risking big, open battles. Birkenmeier argues that John's strategy of launching yearly campaigns with limited, realistic goals was smarter than the one followed by his son Manuel I. According to this view, John's campaigns helped the Byzantine Empire by protecting its central lands, which lacked clear borders, while slowly expanding its territory in Asia Minor. The Turks were forced to defend themselves, and John kept his diplomatic situation relatively simple by allying with the Holy Roman Emperor against the Normans of Sicily.

Overall, it is clear that John II Komnenos left the empire in a much better state than he found it. By the time he died, large areas had been recovered. The goals of regaining control over central Anatolia and re-establishing a border on the Euphrates river seemed possible. However, the Greeks living in the interior of Anatolia were becoming more used to Turkish rule and often preferred it to Byzantine rule. Also, while it was relatively easy to get the Anatolian Turks, Serbs, and Crusader States of the Levant to submit and accept Byzantine authority, turning these relationships into real gains for the empire's security had proven difficult. These problems were left for his talented and unpredictable son, Manuel, to try to solve.

Family Life

John II Komnenos married Princess Piroska of Hungary (who was renamed Irene) in 1104. She was the daughter of King Ladislaus I of Hungary. This marriage was meant to make up for the loss of some lands to King Coloman of Hungary. Irene did not play a big role in government. She focused on her faith and their many children. Irene died on August 13, 1134, and was later honored as Saint Irene.

John II and Irene had 8 children:

- Alexios Komnenos (October 1106 – summer 1142), who was co-emperor from 1119 to 1142.

- Maria Komnene (twin to Alexios), who married John Roger Dalassenos.

- Andronikos Komnenos (died 1142).

- Anna Komnene (around 1110/11 – after 1149), who married the admiral Stephen Kontostephanos. He died in battle in 1149. They had four children.

- Isaac Komnenos (around 1113 – after 1154). He was made sebastokrator in 1122 but was passed over for the throne in favor of Manuel in 1143. He married twice and had several children.

- Theodora Komnene (around 1115 – before May 1157), who married the military commander Manuel Anemas. He was killed in action, and she later entered a monastery. They had at least four children.

- Eudokia Komnene (around 1116 – before 1150), who married the military commander Theodore Vatatzes. She had at least six children but died young.

- Manuel I Komnenos (November 28, 1118 – September 21, 1180), who became emperor and ruled from 1143 to 1180.

See also

In Spanish: Juan II Comneno para niños

In Spanish: Juan II Comneno para niños

- Byzantium under the Komnenos dynasty

- Komnenian army

- List of Byzantine emperors

Sources

- Primary

- Niketas Choniates, critical edition and translation by Magoulias, Harry J., ed. (1984). O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniatēs. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1764-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=O8arrZPM8moC.

- John Kinnamos, critical edition and translation by Brand, Charles M., ed. (1976). Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, by John Kinnamos. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04080-6.

- William of Tyre, Historia Rerum in Partibus Transmarinis Gestarum (A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea), translated by E. A. Babock and A. C. Krey (Columbia University Press, 1943). See the original text in the Latin library.

- Secondary

- Angold, Michael, (1984) The Byzantine Empire 1025–1204, a political history, Longman. ISBN: 978-0-58-249060-4

- Angold, Michael, (1995) Church and Society in Byzantium under the Comneni, 1081–1261. Cambridge University Press.Poetry and its Contexts in Eleventh-century Byzantium

- Bernard, F. and Demoen, K. (2013) Poetry and its Contexts in Eleventh-century Byzantium, Ashgate Publishing

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002). The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11710-5.

- Bucossi, Alessandra and Suarez, Alex R. (2016) John II Komnenos, emperor of Byzantium: in the shadow of father and son, Routledge. ISBN: 978-1-47-246024-0

- Dennis, G.T. (2001) Death in Byzantium, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 55, pp. 1–7, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991). [John II Komnenos at Google Books The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century]. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7. John II Komnenos at Google Books.

- Finlay, George (1854), History of the Byzantine and Greek Empires from 1057–1453, Volume 2, William Blackwood & Sons

- Haldon, John (1999). [John II Komnenos at Google Books Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204]. London: UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-495-X. John II Komnenos at Google Books.

- Harris, Jonathan (2014), Byzantium and the Crusades, Bloomsbury, 2nd ed. ISBN: 978-1-78093-767-0

- Holt, P.M.; Lambton, Ann K.S.; Lewis, Bernard (1995). The Cambridge History of Islam. 1A. Cambridge University Press.

- Hendy, Michael F. (1999). Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection. 4. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 244–274. ISBN 9780884022336. https://archive.org/details/docoins-4/DOCoins_4-1_WEB/page/244/mode/2up.

- Linardou, K. (2016) "Imperial Impersonations", in John II Komnenos, Emperor of Byzantium: In the Shadow of Father and Son, Bucossi, A. and Suarez, A.R. (eds.) pp. 155–182, Routledge, Abingdon and New York. ISBN: 978-1-4724-6024-0

- Loos, Milan (1974) Dualist Heresy in the Middle Ages Vol. 10, Springer, The Hague.

- Magdalino, Paul (1993). The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52653-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=0cWZvqp7q18C.

- Magdalino, P. (2016) "The Triumph of 1133", in John II Komnenos, Emperor of Byzantium: In the Shadow of Father and Son, Bucossi, A. and Suarez, A.R. (eds.) pp. 53–70, Routledge, Abingdon and New York. ISBN: 978-1-4724-6024-0

- Neville, L. (2016) "Anna Komnene: The Life & Work of a Medieval Historian", Oxford University Press.

- Necipoğlu, Nevra (ed.) (2001) Byzantine Constantinople, Brill.

- Norwich, John J. Byzantium; Vol. 3: The Decline and Fall. Viking, 1995 ISBN: 0-670-82377-5

- Ousterhhout, R. (2016) "Architecture and patronage in the age of John II", in John II Komnenos, Emperor of Byzantium: In the Shadow of Father and Son, Bucossi, A. and Suarez, A. R. (eds.), pp. 135–154, Routledge, Abingdon and New York. ISBN: 978-1-4724-6024-0

- Runciman, Steven (1952) A History of the Crusades, Vol. II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press.

- Stathakopoulos, D. (2016) "John II Komnenos: a historiographical essay", in John II Komnenos, Emperor of Byzantium: In the Shadow of Father and Son, Bucossi, A. and Suarez, A. R. (eds.), pp. 1–10, Routledge, Abingdon and New York. ISBN: 978-1-4724-6024-0

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). [John II Komnenos at Google Books A History of the Byzantine State and Society]. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2. John II Komnenos at Google Books.

- Urbansky, Andrew B. Byzantium and the Danube Frontier, Twayne Publishers, 1968

- Varzos, Konstantinos (1984) (in el). Η Γενεαλογία των Κομνηνών. A. Thessaloniki: Centre for Byzantine Studies, University of Thessaloniki. OCLC 834784634. http://www.kbe.auth.gr/sites/default/files/bkm20a1.pdf.

|

John II Komnenos

Komnenian dynasty

Born: 13 September 1087 Died: 8 April 1143 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexios I |

Byzantine emperor 1118–1143 with Alexios I (father) as senior co-emperor (1092–18) Alexios (son) as junior co-emperor (1119–42) |

Succeeded by Manuel I |

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |