Byzantine army (Komnenian era) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Byzantine army of the Komnenian period |

|

|---|---|

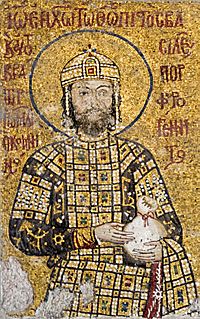

Emperor John II Komnenos, the most successful commander of the Komnenian army.

|

|

| Leaders | Byzantine Emperor |

| Dates of operation | 1081–1204 AD |

| Headquarters | Constantinople |

| Active regions | Anatolia, Southern Italy, Balkans, Hungary, Galicia, Crimea, Syria, Egypt. |

| Size | 50,000 (1143-1180) |

| Part of | Byzantine Empire |

| Allies | Venice, Genoa, Danishmends, Georgia, Galicia, Vladimir-Suzdal, Kiev, Ancona, Hungary, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, Mosul. |

| Opponents | Venice, Hungary, Danishmends, Bulgaria, Seljuks, Antioch, Sicily, Armenian Cilicia, Fatimids, Ayyubids, Pechenegs, Cumans. |

| Battles and wars | Dyrrhachium, Levounion, Nicaea Philomelion, Beroia, Haram, Shaizar, Constantinople (1147), Sirmium, Myriokephalon, Hyelion and Leimocheir, Demetritzes, Constantinople (1203), Constantinople (1204) |

|

|

|

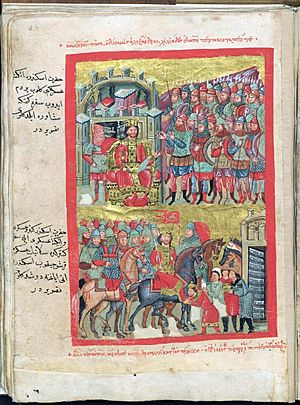

The Byzantine army of the Komnenian era was a powerful fighting force. It was created by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos around the late 1000s and early 1100s. His sons, John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos, made it even stronger.

This new army was very different from earlier Byzantine forces. It relied more on the emperor's own family and nobles. It also used many foreign soldiers, called mercenaries, who were organized into lasting units. This army helped the Byzantine Empire become strong and stable again. It fought in many places, including the Balkans, Italy, Anatolia, and Syria.

Contents

- The Byzantine Army: A New Beginning

- How Big Was the Army?

- How the Army Was Paid and Supported

- How the Army Was Organized

- Weapons and Armor of the Byzantine Army

- Big Guns: Byzantine Artillery

- Different Kinds of Soldiers

- How the Army Changed Over Time

- What Happened Next?

- Key Moments in the Army's History

- Images for kids

The Byzantine Army: A New Beginning

In 1081, the Byzantine Empire was in a tough spot. It was smaller than ever and surrounded by enemies. Years of internal conflicts had left the empire weak and without much money.

The old Byzantine army had almost disappeared. Important units, some with roots going back to the Roman Empire, were gone. After a big defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the empire lost a lot of land in Anatolia. This area had been a main place for finding new soldiers.

Things got even worse in 1081 at the Battle of Dyrrhachium. Emperor Alexios I was badly beaten by the Normans from southern Italy. By 1091, Alexios could only gather about 500 regular soldiers.

But Alexios, along with his son John and grandson Manuel, worked hard to rebuild the empire. They improved finances and spent years campaigning. They created a new, strong army. At first, Alexios had to make changes out of urgent need, not from a grand plan.

The new army had a core of skilled and disciplined soldiers. This included special guard units like the Varangians. It also had the vestiaritai, vardariotai, and archontopouloi. The archontopouloi were sons of dead Byzantine officers.

The army also had foreign mercenary groups. Plus, it included professional soldiers from different regions. These regional troops included heavy cavalry called kataphraktoi from places like Macedonia. The new army also used armed followers of the emperor's family and local nobles. This was a bit like the feudal system in Western Europe.

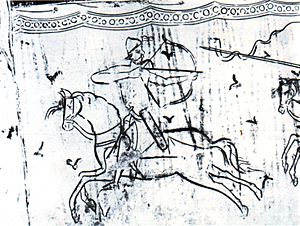

During this time, there aren't many detailed books about Byzantine military tactics. So, we learn about their army from historical stories and pictures.

How Big Was the Army?

It's hard to know the exact size of the Byzantine army during this period. There are no detailed records left. Historians note that Alexios I struggled to find enough soldiers at first.

But later, John II could field armies as large as those of the Kingdom of Hungary. Manuel I even gathered an army strong enough to defeat a large crusader force.

Some historians guess that Alexios I's field army had about 20,000 men. By 1143, the whole Byzantine army might have been around 50,000 soldiers. This size likely stayed the same until Manuel's reign ended.

About 25,000 of these were mobile professional and mercenary troops. The rest were static garrisons and local militias. The European provinces could provide over 6,000 cavalry. The Eastern provinces in Anatolia provided about the same number. This meant over 12,000 cavalry for the empire, not counting allies.

Armies on campaign usually had 15,000 to 20,000 men. But armies with fewer than 10,000 soldiers were common. In 1176, Manuel I gathered about 30,000-35,000 men for a special campaign. About 25,000 were Byzantines, and the rest were allies.

After Manuel I died, the army's numbers seemed to shrink. In 1186, Isaac II gathered about 2,500 men to fight a rebellion. This force included knights, infantry, and mercenaries.

How the Army Was Paid and Supported

The Byzantine army of this time was supported in different ways. Some soldiers were paid directly by the government. Others were supported by nobles who had their own armed followers. Sometimes, defeated enemies were even forced to join the army.

Paying the Soldiers

The empire's money situation got much better during the Komnenian period. At first, Alexios I had to melt down church gold to pay his troops. But his successors, John and Manuel, could spend huge amounts on the army.

The Byzantine emperor could raise money quickly. Alexios reformed the currency in 1092. He introduced a high-quality gold coin called the hyperpyron. He also improved the tax system.

Even though Alexios sometimes had to find money in unusual ways, the goal was to use regular taxes to support the military. Paying soldiers with salaries and annual payments was the preferred method. We don't have many records of exact pay rates for soldiers from this time. However, a Western knight was probably paid more than a Turkish horse archer.

The 'Pronoia' System

The pronoia system became important for supporting the army later in this period. A pronoia was like a grant of land rights. The holder could collect taxes from that land. In return, they had to provide military service.

Pronoia holders lived on their land and collected their income directly. This saved money on bureaucracy. It also ensured soldiers had an income whether they were fighting or on guard duty. The pronoiar also had a reason to keep their land productive and defend it.

The local people working the land also provided labor. This made the system somewhat like feudalism. However, pronoia was not strictly passed down through families. While Manuel I expanded this system, paying troops with cash remained the main method.

How the Army Was Organized

Leaders and Units

The emperor was the supreme commander. Below him, the army's commander-in-chief was the megas domestikos. His second-in-command was the prōtostratōr. The navy was led by the megas doux. This person also commanded forces in Crete and the Aegean Islands.

A general leading a large army division was called a stratēgos. Provinces and their defenses were managed by a doux or katepanō. A fortress was commanded by a kastrophylax.

Smaller units were named after their size. For example, a tagmatarchēs led a tagma (regiment). The leader of the Varangians had a special title, akolouthos.

The main cavalry unit was the allagion, with 300 to 500 men. It was divided into smaller groups of 100, 50, and 10. Infantry units were called taxiarchia, usually 1,000 men strong. They were led by a taxiarchēs.

Elite Guards and the Emperor's Troops

Many old guard units didn't survive Alexios I's reign. But the Varangians and vestiaritai did. The hetaireia (companions) also continued.

The Varangian Guard was made up of Englishmen, Russians, and Scandinavians. They numbered about 5,000 men. Alexios I also created the archontopouloi unit with 2,000 men. The Vardariots, a cavalry unit, were added later by John II.

The oikeioi (household troops) were very important. These were the emperor's personal soldiers, including his relatives and close friends. They were like the household knights of Western kings. They had the best weapons, armor, and horses.

The oikeioi were a powerful fighting force. They were only available when the emperor himself went to battle. Alexios I also used his household to train young officers. This helped improve the army's discipline and the loyalty of its commanders.

Soldiers from the Empire

Over time, the old part-time soldier-farmers were replaced by smaller, full-time regiments. Only the provincial regiments from the southern Balkans survived the chaos of the late 1000s. These soldiers became a key part of the main army.

As the empire regained land, new provincial forces were set up. These often served as local garrisons. Manuel I's historian mentioned "eastern and western tagmata." This suggests that regular regiments were again being raised in Anatolia.

Military settlers, often defeated enemies, also provided soldiers. For example, defeated Pechenegs were settled in one area and formed a unit. Serbs were settled near Nicomedia in Anatolia.

Later, the pronoia system helped raise heavy cavalry. This reduced the direct cost to the government. Most records from this time are about cavalry. We know less about the native infantry. There was a list of infantry soldiers, but their origins are unclear. Infantry were crucial for sieges.

Foreign Fighters and Allies

The main army also included regiments of foreign soldiers. These included the latinikon, a heavy cavalry unit of Western European knights. Many of these families had served the Byzantines for generations. They were paid by the state, not just temporary mercenaries.

Another unit was the tourkopouloi (sons of Turks). These were Byzantinized Turks or mercenaries from the Seljuk Sultanate. The skythikon was made up of Turkic Pechenegs and Cumans.

Alexios I even recruited 3,000 Paulicians and 7,000 Turks. Foreign mercenaries and soldiers from allied groups, like the Serbs, also joined. These troops usually fought under a Byzantine general.

The Byzantines often mixed different ethnic groups within their army. This helped prevent all soldiers of one nationality from switching sides during battle. For example, Serbs had to send cavalry when the emperor campaigned in Anatolia. Later, this number increased.

Alan soldiers became important in Byzantine armies later on. It's worth noting that there were no major mutinies by foreign troops between 1081 and 1185.

Nobles and Their Private Armies

Nobles and powerful families also had their own armed followers. These were a useful addition to the Byzantine army. During Alexios I's reign, these private armies probably made up a large part of many field armies.

Some leading families became very powerful. They could raise many troops from their followers, relatives, and tenants. These troops were called oikeoi anthropoi (household men). Their quality might not have been as good as the professional state troops.

Generals who were also aristocrats had their own "personal guards." These were like smaller versions of the emperor's household troops. For example, Isaac Komnenos, John II's brother, had his own guard unit.

The guard of the megas domestikos John Axouch was large enough to stop a riot. This happened between Byzantine troops and allied Venetians during a siege in 1149.

Weapons and Armor of the Byzantine Army

The weapons and armor of the Byzantine army in the late 1000s and 1100s were advanced. They were often more complex than those in Western Europe. Byzantium learned from the Muslim world and the Eurasian steppes. These areas were good at inventing new military equipment. Byzantine armor was very effective, even better than Western European armor until the 1300s.

What Weapons Did They Use?

Close-combat soldiers, both infantry and cavalry, used spears. These were called kontarion. Specialist infantry used a heavy weapon called the menavlion, but its exact form is unclear.

Swords came in two types. The spathion was a straight, double-edged sword, similar to Western European swords. The paramērion was a single-edged, possibly curved, sabre. Most soldiers carried swords as secondary weapons. Heavy cavalry sometimes carried both types.

Light infantry used a small axe called a tzikourion. The Varangians were famous for their two-handed Danish axe. The rhomphaia was a unique weapon carried by guards near the emperor. It was carried on the shoulder, but sources disagree if it was single or double-edged. Heavy cavalry also used maces. Byzantine maces had various names, suggesting different designs.

For ranged attacks, light infantry used javelins called riptarion. Both infantry and cavalry used powerful composite bows. Byzantine bows were originally from the Huns, but Turkish bows became common. These bows could fire short bolts using an 'arrow guide'. Slings were also used.

Shields for Protection

Shields, called skoutaria, were usually long and shaped like a "kite." Round shields were also still seen in pictures. All shields were strongly curved. A large, pavise-like shield might have been used by infantry.

Body Armor: Staying Safe in Battle

The Byzantines used a lot of 'soft armor'. This was made of quilted, padded fabric, similar to the "jack" or aketon in the West. This garment, called the kavadion, usually reached the knees and had sleeves. It was often the only protection for lighter troops.

Heavier troops wore the kavadion under metal armor. Another padded armor, the epilōrikion, could be worn over a metal cuirass.

Metal body armor included mail (lōrikion alysidōton), scale (lōrikion folidōton), and lamellar (klivanion). Mail and scale armor were like those in Western Europe. They were shirts reaching the mid-thigh or knee with elbow-length sleeves.

The lamellar klivanion was different. It was made of metal plates riveted to leather bands. These bands were laced together, overlapping vertically. This armor was very good at stopping piercing and cutting weapons. It was expensive to make, so it was likely used by heavy cavalry and elite units.

Because lamellar armor was less flexible, the klivanion only covered the torso. It didn't have sleeves and reached only to the hips. It was often worn with other armor parts. It could be worn over a mail shirt. More commonly, it was worn with tubular upper arm defenses. These were often made of splinted construction with shoulder cops.

A skirt called the kremasmata was often worn with the klivanion. This skirt was padded or pleated fabric, often reinforced with metal splints. It protected the hips and thighs.

Armor for the forearms was mentioned in older writings but is not often seen in pictures from this period. Most images show knee-high boots as the only lower leg protection. A few images show tubular greaves, which would be called podopsella.

Helmets: Protecting Their Heads

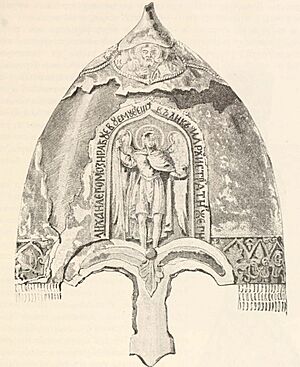

Pictures of soldier-saints usually show them bare-headed, so they don't help with helmet information. Manuscript illustrations are small and lack detail. However, we can still describe some helmets.

The 'Caucasian' type helmet, a tall, pointed spangenhelm, was used. Conical helmets and those with a forward-pointing top (like a Phrygian cap) were also seen. These often had a single-piece skull. More rounded helmets, possibly from older Roman designs, were also illustrated.

Few Byzantine helmets have been found by archaeologists. A helmet from Yasenovo, Bulgaria (10th century), might be a Byzantine style. It's rounded, with a brow-band for attaching a face-covering. A high-quality Byzantine helmet from Romania (late 12th century) is similar but taller and conical.

Another helmet from the same place is like the Russian helmet shown here. It has a fluted, conical skull and gilding. It's called a Russo-Byzantine helmet. A very tall, elegant 'Phrygian cap' helmet from Pernik, Bulgaria (late 12th century), also had a nasal piece.

In the 1100s, the brimmed ‘chapel de fer’ helmet began to appear. This might have been a Byzantine invention.

Most Byzantine helmets had neck armor. Sometimes, throat protection was also included. Full face protection was rare but mentioned. This usually meant a skirt of quilted fabric or metal strips hanging from the helmet. Other helmets had a mail aventail or camail attached to the brow-band.

Face protection is mentioned three times in writings from this period. This likely refers to mail covering the face, leaving only the eyes visible. Metal 'face-mask' visors were also found in Constantinople. These masks might be what the writings describe.

Horse Armor

There are no Byzantine pictures of horse armor from the Komnenian period. The only description is of Hungarian horse armor at the Battle of Sirmium. However, older writings mention horse armor, and a later Byzantine illustration shows it.

So, it's likely that Byzantines continued to use horse armor. It was probably limited to very rich kataphraktoi, nobles, and some guard units. Horse armor could be made of metal or rawhide plates, or padded fabric. Historians believe Byzantine lancers used armored horses for their charges.

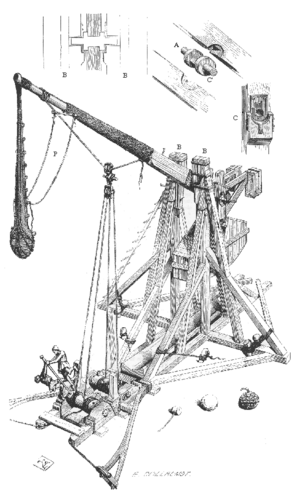

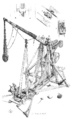

Big Guns: Byzantine Artillery

The Komnenian army had powerful artillery. Their stone-throwing and bolt-firing machines were feared by enemies. They used them to attack and defend fortresses and cities.

The most famous war machines were stone-throwing trebuchets, often called helepolis (city-takers). The Byzantines knew about both man-powered and the more powerful counterweight trebuchets. Some Western writers even said the Byzantines invented the trebuchet.

The Byzantines also used long-range, anti-personnel machines. These included the 'great crossbow' on a mobile base. They also used the 'skein-bow' or 'espringal', which used twisted ropes for power.

Byzantine artillerists were highly respected. Emperor John II and generals Stephanos and Andronikos Kontostephanos were recorded personally operating siege engines.

Different Kinds of Soldiers

The Byzantine Empire was a developed society with a long military history. It could recruit soldiers from many different peoples. This meant its army had a wide variety of troop types.

Foot Soldiers

Byzantine infantry, except for the Varangians, are not well described in historical sources. Emperors and nobles, who were the main focus of historians, were linked to the high-status heavy cavalry. So, infantry got little mention.

The Mighty Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard were the best infantry. In battle, they were heavy infantry. They wore good armor, carried long shields, and used spears and their famous two-handed Danish axes. They were known for aggressive attacks.

At Dyrrhachion, they defeated a Norman cavalry charge. But they pushed too far and were broken. At Beroia, the Varangians were more successful. John II led them personally. They broke into the Pecheneg wagon fort and won a complete victory.

Varangians likely rode horses when traveling but fought on foot. About 4,000–5,000 Varangians joined the Byzantine army during Alexios I's reign. Emperors usually brought around 500 Varangians for personal protection on campaigns. A Varangian garrison was also stationed in Paphos in Cyprus.

Heavy Foot Soldiers

Heavy infantry are rarely mentioned in sources. In earlier times, a heavy infantryman was called a skoutatos (shieldbearer). These terms are not used in the 1100s. Historians used terms like kontophoros (spearbearer).

Byzantine heavy infantry used long spears. Some might have used the menavlion polearm. They carried large shields and wore as much armor as possible. Those in the front ranks likely had metal armor, perhaps even a klivanion.

These infantrymen fought in tight ranks. Their role was mostly defensive. They formed a strong wall against enemy cavalry charges. They also created a safe base for cavalry and other mobile troops to attack from and return to.

Fast-Moving Peltasts

The term peltast (peltastēs) is mentioned more often than "spearman." In ancient times, peltasts were light skirmish infantry with javelins. But in the Komnenian period, they were sometimes called "assault troops."

Komnenian peltasts seem to have been lightly equipped. They were very mobile in battle. They could skirmish but also fight in close combat. They might have used a shorter version of the kontarion spear. At Dyrrachion, peltasts even drove off Norman cavalry. They sometimes worked with heavy cavalry.

Light Foot Soldiers

The true light infantry of the Byzantine army were the psiloi. This term included foot archers, javelineers, and slingers. They were usually unarmored. The psiloi were different from peltasts.

These troops usually carried a small shield for protection. They also had a secondary weapon, like a sword or light axe, for close combat. They could fight from behind heavy infantry or skirmish ahead. Light troops were very effective in ambushes, like at the Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir in 1177.

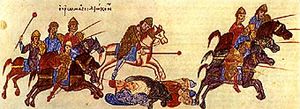

Horse Soldiers

The earlier Byzantine heavy cavalry, who used both a bow and a lance, seemed to disappear. The typical heavy cavalryman of the Komnenian army was a dedicated lancer. But armored horse-archers were still used.

Strong Heavy Cavalry

Heavy cavalry were the social and military elite. They were seen as the main force for winning battles. A charge by lancers, followed by close fighting, often decided the battle. Komnenian heavy cavalry came from two groups: 'Latin knights' and native kataphraktoi.

Western Knights in the Army

Latin heavy cavalry came from Italy, France, Germany, and the Crusader States. Byzantines thought French knights were stronger fighters than Germans. Some Latin cavalry were regular soldiers, paid by the empire or through pronoia grants. They were organized into regiments.

Regular Latin knights were part of the guard. Others were grouped into a unit called the latinikon. Sometimes, mercenary knights were hired for specific campaigns. The Byzantines greatly respected the charge of Western knights. Anna Komnene said, "A mounted Kelt [Norman or Frank] is irresistible."

Their equipment and tactics were like those from their home regions. But their appearance likely became more Byzantine the longer they served. Some Latin soldiers became fully part of Byzantine society. Their descendants often continued military service.

The Famous Kataphraktoi

Native kataphraktoi were found in the emperor's household, some guard units, and generals' personal guards. But most were in the provincial regiments. The quality of individual kataphraktos soldiers varied. John II and Manuel I sometimes combined "picked lancers" from different units. This might have been to recreate the strong heavy cavalry of earlier times.

Kataphraktoi were the most heavily armored Byzantine soldiers. A rich kataphraktos could be very well protected. The Alexiad tells how Emperor Alexios was attacked by Norman knights from both sides. His armor was so good that he wasn't seriously hurt.

Early in Alexios I's reign, Byzantine kataphraktoi couldn't stand up to Norman knight charges. Alexios had to use tricks to avoid such charges. Byzantine armor was probably better than Western armor. So, the problem wasn't the armor.

It's likely that Byzantine heavy cavalry traditionally charged at a slower speed. The Normans developed a fast, disciplined charge that had great power. This outmatched the Byzantines. The use of the couched lance and improved saddles might have played a role.

The Byzantines may have had trouble getting good warhorses after losing land in Anatolia. But by Manuel I's reign, Byzantine kataphraktos soldiers were equal to their Western counterparts. Manuel was said to have introduced Western knightly equipment and techniques. He also enjoyed jousting, which likely improved his heavy cavalry's skills. The kataphraktos was also known for using a powerful iron mace in close combat.

Fast-Moving Koursores

A type of cavalryman called a koursōr is mentioned in Byzantine military writings. The term means 'raider'. Some think it's the origin of the word hussar. Koursores were mobile close-combat cavalry. They were probably lighter kataphraktoi.

Their main job was to fight enemy cavalry. They were usually placed on the flanks (sides) of the main battle line. Those on the left defended against enemy attacks. Those on the right attacked the enemy's flank. Cavalry on scouting or screening duty were also called prokoursatores.

These cavalry were likely armed like heavy kataphraktoi but had lighter armor. They rode faster horses. Being lighter, they were better at chasing fleeing enemies. When the heavier kataphraktoi were separated into "picked lancers," the remaining lighter ones likely became koursores.

Light Horse Archers

The light cavalry of the Komnenian army were horse-archers. There were two types: lightly equipped skirmishers and heavier, often armored, bow-armed cavalry. The native Byzantine horse-archer was the heavier type. They fired arrows from disciplined ranks, providing mobile missile fire.

Native horse-archers became less common. They were largely replaced by foreign soldiers. However, in 1191, Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus fired arrows from horseback at Richard I of England. This shows that mounted archery was still practiced by some Byzantine nobles.

Turks from the Seljuk and Danishmend areas, and Byzantinized Turks and Magyars, provided most of the heavy horse-archers. These included the Vardariots. Later, Alans also supplied this type of cavalry. These horse archers were often very disciplined.

At Sozopolis in 1120, Byzantine horse-archers performed a fake retreat. This required great confidence and discipline. It led to the capture of the city from the Turks. Since they were usually armored, these horse-archers could also fight in close combat.

Light skirmish horse-archers were usually unarmored. They came from Turkic Pechenegs, Cumans, and Uzes. These troops were excellent scouts and good at harassing enemies. They attacked in swarms and were hard for heavily equipped enemies to catch. Light horse-archers were also good at screening, hiding the main army's positions.

How the Army Changed Over Time

Alexios I took over an army that had been carefully rebuilt. This army was small due to lost land and money. But it was similar to earlier Byzantine armies. However, this traditional army was destroyed by the Normans at Dyrrachion in 1081.

After this disaster, Alexios started building a new military. He raised troops in new ways. He created the archontopouloi from sons of dead soldiers. He even forced Paulicians, a religious group, to join. The only Anatolian troops mentioned were the Chomatenes.

Most importantly, Alexios's large family played a big role. Each noble brought his armed followers to battle. The army, like the empire, became a bit like a family business. At this point, it was a feudal army with many mercenaries.

Later in his reign, the empire recovered land and money. Alexios could then make the army more regular. A higher number of troops were directly paid by the state. But the imperial family still had a very important role.

Alexios personally trained a group of young, promising commanders. The best of them were given army commands. This improved the quality of his officers and their loyalty to him. His successors continued and changed this army.

Under John II, new Byzantine troops were recruited from the provinces. As Byzantine Anatolia became richer, more soldiers came from Asian provinces. Soldiers were also taken from defeated peoples and settled as military colonists. These included Pechenegs and Serbs.

Native troops were organized into regular units in both Asian and European provinces. Later Komnenian armies often had allies from Antioch, Serbia, and Hungary. Still, about two-thirds of the army were Byzantine troops.

Archers, infantry, and cavalry were grouped to support each other. Field armies had a vanguard, main body, and rearguard. The vanguard and rearguard could operate alone. This shows that commanders were well-trained and trusted.

John fought fewer big battles than his father or son. His strategy focused on sieges and holding fortified places to create strong borders. John personally led about 25 sieges during his reign.

Emperor Manuel I was very influenced by Westerners. At the start of his reign, he reportedly re-equipped and retrained his heavy cavalry like Western knights. It's thought that Manuel introduced the couched lance technique and fast, close-order charges. He also increased the use of heavier armor.

Manuel enjoyed Western-style jousting tournaments. His skill impressed Western observers. Manuel organized his army into divisions for the Myriokephalon campaign. Each division could act as a small, independent army. This organization may have helped most of his army survive a Turkish ambush.

Manuel is also credited with greatly expanding the pronoia system. Alexios I had limited pronoia grants to his family. Manuel extended it to people of lower social rank and foreigners. This angered some historians, who called the new pronoiars "tailors, bricklayers and semi-barbarian runts."

Permanent military camps were set up in the Balkans and Anatolia. These were first mentioned under Alexios I. But John II seems to have fully developed them. The main Anatolian camp was at Lopadion. The European one was at Kypsella. Others were at Sofia and Pelagonia.

Manuel I rebuilt Dorylaion in Anatolia for his Myriokephalon campaign. These large military camps were new for the Komnenian emperors. They might have been an improved form of earlier military stations. They probably played a big role in making the Byzantine forces more effective.

The camps were used for training troops and preparing armies for campaigns. They also served as supply depots and meeting points for armies. It's thought that pronoia grants were often located near these military bases.

What Happened Next?

The Komnenian Byzantine army was strong and effective. But it relied heavily on a skilled emperor. After Manuel I died in 1180, there was no strong leader. First came Alexios II, a child emperor. Then Andronikos I, a tyrant who tried to weaken the nobles who led the army. Finally, the Angeloi dynasty brought weak leaders.

Weak leadership caused the Komnenian system to fall apart. Powerful nobles started rebelling and breaking away. There was a lot of distrust between the nobles and the government in the capital. These problems weakened the empire.

When Constantinople fell to the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Byzantine successor states were formed. These included Epirus, Trebizond, and especially Nicaea. They all based their military systems on the Komnenian army.

The Empire of Nicaea successfully reconquered former Byzantine lands, including Constantinople. This shows how strong the Komnenian army model was. The term Komnenian army usually refers to the period of the Komnenian emperors. But the real change happened after Constantinople was recovered in 1261. At that point, the Byzantine army became different enough to be called the Palaiologan army.

The Byzantine Empire had a period of economic and cultural growth in the 1100s. The Komnenian army was crucial in providing the stability that allowed this to happen.

Key Moments in the Army's History

- 1081 – Alexios I led 20,000–25,000 men against invading Normans. He was heavily defeated at the Battle of Dyrrhachion.

- 1083 – Alexios rebuilt his army to 15,000 men. He decisively defeated the Norman army at the Battle of Larissa.

- 1091 – A huge invasion by the Pechenegs was stopped. A Byzantine army, with 5,000 Vlach mercenaries, 500 Flemish knights, and 40,000 Cumans, won the Battle of Levounion.

- 1092–1097 – John Doukas, the megas doux, led campaigns on land and sea. He brought the Aegean, Crete, Cyprus, and western Anatolia back under Byzantine control.

- 1107–1108 – The Normans under Bohemond invaded the western Balkans. Alexios defended mountain passes, trapping the Norman army on the Albanian coast. His navy cut off their supplies. Alexios starved them into surrendering.

- 1116 – The Battle of Philomelion was a series of clashes. Alexios I's army fought the Sultanate of Rûm. The Byzantine victory led to a good peace treaty for the empire.

- 1119 – The Seljuks had cut off the land route to Attalia and Cilicia. John II campaigned to recapture Laodicea and Sozopolis. This restored Byzantine control and communication.

- 1122 – At the Battle of Beroia, John II personally led 500 Varangians. They broke through the Pecheneg defensive wagon fort. The Pechenegs disappeared from history after this defeat.

- 1128 – An army led by John II defeated the Hungarians at the Battle of Haram on the River Danube.

- 1135 – John II captured Kastamon and then Gangra. Gangra surrendered and was garrisoned with 2,000 men.

- 1137-1138 – John II regained control of Cilicia. He forced the Crusader Principality of Antioch to become his vassal. He also campaigned against Muslims in Northern Syria. The city of Shaizar was besieged with 18 large catapults.

- 1140 – John II besieged Neocaesarea but failed to take it. The Byzantines were defeated by bad weather, horse deaths, and lack of supplies.

- 1147 – At the Battle of Constantinople, a Byzantine army defeated part of Conrad III of Germany's crusader army. Conrad had to agree to terms and quickly ship his army across to Anatolia.

- 1148 – Manuel I learned of a Cuman raid. He sent his army to the Danube. He personally crossed the Danube with 500 cavalry and defeated the Cuman raiding party.

- 1149 – Manuel I commanded 20,000–30,000 men at the siege of Corfu. He was supported by a fleet of 50 galleys and many other ships.

- 1155–56 – Generals Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas invaded Apulia with 10 ships. They captured several towns, but the expedition failed. The Byzantine fleet was greatly outnumbered by the Norman fleet.

- 1158 – Manuel I led a large army against Thoros II of Armenia. He left the main army at Attaleia and led 500 cavalry into Cilicia for a surprise attack.

- 1165 – A Byzantine army invaded the Kingdom of Hungary. The city of Zeugminon was besieged. General Andronikos I Komnenos personally adjusted the 4 large catapults used to bombard the city.

- 1166 – Two Byzantine armies attacked the Hungarian province of Transylvania in a pincer movement. One army crossed the Walachian Plain. The other went through Galicia with their help.

- 1167 – General Andronikos Kontostephanos led 15,000 men. He won a decisive victory over the Hungarians at the Battle of Sirmium.

- 1169 – A Byzantine fleet of about 150 galleys and many transports invaded Egypt. The combined Byzantine-Crusader army captured Tounion and Tinnis. They then besieged Damietta. King Amalric made peace and withdrew. The Byzantine fleet left after over 50 days.

- 1175 – The Emperor sent Alexius Petraliphas with 6,000 men to capture Gangra and Ancyra. But the expedition failed due to strong Turkish resistance.

- 1176 – Manuel I led a large army of 25,000–40,000 men to capture Iconium. The campaign failed after a defeat at the Battle of Myriokephalon.

- 1177 – Andronikos Kontostephanos led 150 ships in another attempt to conquer Egypt. The force returned home after landing at Acre. A large raiding force of Seljuk Turks was destroyed by a Byzantine army in an ambush in Western Anatolia (Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir).

- 1185 – After the Normans sacked Thessalonica, a Byzantine army led by Alexios Branas routed the Norman army at the Battle of Demetritzes. Thessalonica was quickly re-occupied.

- 1187 – General Alexios Branas rebelled. Conrad of Montferrat gathered 250 knights and 500 infantry from Constantinople. They joined Emperor Isaac II Angelos's army of 1,000 men. Together, they defeated and killed the rebel commander. Later, the Emperor returned to Bulgaria with 2,000 men to stop the rebellion.

- 1189 – Emperor Isaac II ordered the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes to ambush part of Frederick Barbarossa's army. Kamytzes, with 2,000 cavalry, was defeated near Philippopolis.

- 1198–1203 – There were several revolts by powerful local leaders. Some were stopped, but others in Greece succeeded.

- 1204 – When the Fourth Crusade reached Constantinople, the city was defended by 10,000 men. This included the Imperial Guard of 5,000 Varangians.

Images for kids

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |