Kingdom of Georgia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Georgia

საქართველოს სამეფო

Sakartvelos samepo |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1008–1490 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Coat of arms of "All-Georgian Kingdom" according to Prince Vakhushti's Atlas (c. 1745)

Coat of arms of the "Kingdom of Georgia under Khan" according to Grünenberg Wappenbuch (1480)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kingdom of Georgia in c. 1220, at the peak of its territorial expansion, superimposed on modern borders.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

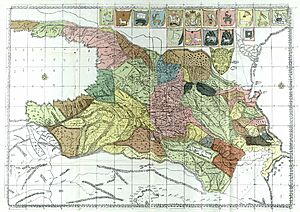

Administrative division of the Kingdom of Georgia in the 13th century

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Georgian Greek Laz Armenian Arabic (lingua franca/numismatics/chancery) Persian (numismatics) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy (Georgian Patriarchate) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1008–1014 (first)

|

Bagrat III | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1446–1465 (last)

|

George VIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of State | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | High Middle Ages to Late Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Unification

|

c. 1008 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Georgian Golden Age

|

1122–1226 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1245–1247 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• East and West division

|

1247–1329 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Reunification

|

1329 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

1463 1490 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Various Byzantine and Sassanian coins were minted until the 12th century. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1the full title of the Georgian monarchs after 1124 was "King of Kings, Autocrat of all the East and the West, Sword of the Messiah, King of Abkhazia, King of Iberia, King of Kakheti and Hereti, King of Armenia, Possessor of Shirvan."

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

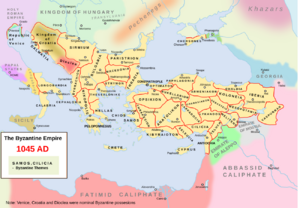

The Kingdom of Georgia (in Georgian: საქართველოს სამეფო, Sakartvelos samepo), also known as the Georgian Empire, was a powerful kingdom in Eurasia during the Middle Ages. It was founded around 1008 AD. This kingdom became very strong politically and economically during the time of King David IV and Queen Tamar the Great, from the 11th to the 13th centuries.

Georgia became one of the most important Christian nations in the East. Its influence and control stretched from Eastern Europe to Anatolia and the northern parts of Iran. Georgia also owned religious places in other countries, like the Monastery of the Cross in Jerusalem and the Monastery of Iviron in Greece. This kingdom is the main historical ancestor of the country we know today as Georgia.

The Kingdom of Georgia lasted for several centuries. However, it faced major challenges, including Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Even though it was weakened, Georgia managed to regain its independence by the 1340s. The years that followed were difficult. The Black Death (a terrible plague) hit the country, and there were many invasions led by Timur. These events badly damaged Georgia's economy, reduced its population, and destroyed its cities.

The situation for the kingdom got even worse after the Ottoman Turks conquered the Byzantine Empire and the Empire of Trebizond. Because of all these problems, by the end of the 15th century, Georgia broke apart. This led to the final collapse of the kingdom around 1466. By 1490-1493, its parts became independent states: the Kartli, Kakheti, and Imereti. Each of these was ruled by a different branch of the Bagrationi royal family. Five smaller, semi-independent areas also formed: Odishi, Guria, Abkhazia, Svaneti, and Samtskhe.

Contents

How Georgia Became a Kingdom

Early Kingdoms and Arab Rule

Long ago, early Georgian kingdoms were divided into smaller areas during wars between the Romans and Persians. Later, in the 7th century, the region came under the control of early Muslim armies.

Princes from the Bagrationi dynasty fought against the Arab rulers. They eventually took control of the Tao-Klarjeti region. They created the Kouropalatate of Iberia, which was somewhat under the control of the Byzantine Empire. By 888, they had gained control of the central Georgian land, Kartli, and brought back the Iberian kingship. However, the Bagrationi family couldn't keep their kingdom together, and it split into three parts.

In 736, an invasion by Marwan ibn Muhammad was stopped by the people of Abkhazia, Lazica, and Iberia. This successful defense, along with ongoing struggles against the Byzantines, helped unite the Georgian states into one kingdom. The Georgian Church also became independent from Constantinople in the 9th century. Its main language changed from Greek to Georgian.

Uniting the Georgian State

In the 10th century, David III of Tao took over the Duchy of Kartli. He gave it to his adopted son, Bagrat III of Georgia. Bagrat's father, Gurgen of Iberia, ruled as regent. In 994, Gurgen became King of the Iberians. In 975, Bagrat became King of the Kartlians.

At this time, the Kingdom of Abkhazia was ruled by Theodosius the Blind. The Abkhazian nobles were unhappy with Theodosius. In 978, they removed him and asked Bagrat to become King of Abkhazia.

When Gurgen died in 1008, Bagrat inherited his throne. This made Bagrat the first king to unite Abkhazia and Iberia. Early in his rule, Bagrat also took over the kingdom of Kakheti-Hereti in the east in 1010. Bagrat also reduced the power of local princes to make his kingdom stronger. He even tricked and imprisoned some of his cousins to secure the throne for his son, George I of Georgia.

Bagrat's rule brought an end to many power struggles in the region. He kept peace with the Byzantines and nearby Muslim areas. However, some territories like Tao and Tbilisi remained under Byzantine and Arab control.

Major Events in Georgian History

Wars with the Byzantine Empire

The rule of George I was mostly known for wars against the Byzantines. This conflict started because David III of Tao had promised his lands in Tao to the Byzantine Emperor Basil II after his death. George I tried to take these lands back around 1015 or 1016.

Basil II, after dealing with Bulgaria, focused on Georgia. This led to a two-year war that the Byzantines won. As a result, George had to give up his claims in Tao and some southwestern lands. George's son, Bagrat IV, was also given to Basil as a hostage.

Bagrat IV was released in 1025. When George I died in 1027, 8-year-old Bagrat became king. By then, the Bagratid family's goal of uniting Georgia was strong. But many Georgian lands were still controlled by foreign empires or independent kings. The loyalty of Georgian nobles was also a problem. During Bagrat IV's childhood, the nobles gained more power, which he tried to stop when he became a full ruler.

The Great Turkish Invasion

In the late 11th century, the Seljuq Turks invaded nearby regions. This made the Georgian and Byzantine governments work together more closely. Bagrat's daughter, Maria, married the Byzantine co-emperor Michael VII Ducas.

In 1065, the Seljuk sultan Alp Arslan attacked Kartli, took Tbilisi, and built a mosque. Later, George II of Georgia defeated a Seljuk governor in 1074. In 1076, the Seljuk sultan Malik Shah I attacked again. Georgia eventually agreed to pay an annual tribute to Malik Shah for peace.

Georgia's Golden Age

King David IV the Builder

George II gave the crown to his 16-year-old son David IV in 1089. With the help of his minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV reduced the power of the feudal lords and made the central government stronger. From 1089 to 1100, he organized military actions to defeat Seljuk troops. In 1099, David IV stopped paying tribute to the Seljuqs.

By 1104, David IV's supporters captured the king of eastern Georgia, Aghsartan II, reuniting the area. The next year, David IV defeated a Seljuk army in the Battle of Ertsukhi. Between 1110 and 1118, David IV captured several important fortresses.

From 1118 to 1120, David IV made big changes to his army. He brought in thousands of Kipchaks to settle in Georgia. In return, each Kipchak family provided a soldier, helping him create a strong standing army. This alliance was strengthened by David IV's marriage to the Kipchak leader's daughter.

In 1120, David IV became more focused on expanding his kingdom. He invaded the nearby Shirvan area and the town of Qabala. From there, he successfully attacked the Seljuks in the eastern and southwestern parts of Transcaucasia. In 1121, Sultan Mahmud b. Muhammad declared a holy war on Georgia. But David IV defeated his large army at the Didgori. Soon after, David IV took Tbilisi, one of the last Muslim areas in Georgia. The capital was moved there, starting Georgia's Golden Age.

In 1123, David IV freed Dmanisi, the last Seljuk stronghold in southern Georgia. By 1124, Shirvan was captured, along with the Armenian city of Ani. This expanded the kingdom's borders to the Araxes river.

David IV also founded the Gelati Academy, which was known as "a new Hellas" and "a second Athos." David also wrote Hymns of Repentance, which were eight free-verse psalms.

Demetrius I and George III

The kingdom continued to do well under Demetrius I, David's son. Demetrius allowed different religions in his kingdom. He even gave tax breaks and religious rights to Muslims in Tbilisi. Despite this, neighboring Muslim rulers attacked Georgia.

In 1139, Demetrius raided the city of Ganja. He brought the iron gate from the defeated city to Georgia and gave it to Gelati Monastery in Kutaisi. Even with this victory, Demetrius could only hold Ganja for a few years.

Demetrius was a talented poet. He continued his father's work in Georgian religious music. His most famous hymn is Thou Art a Vineyard.

Demetrius was followed by his son George III in 1156. George III started a more aggressive foreign policy. In 1161, George III took over Ani and made his general Ivane Orbeli its ruler. A group of Muslim rulers formed an alliance against Georgia, but George III defeated them. In 1162, the Georgian army took Dvin.

Later, a group of Muslim rulers led by Eldiguz attacked Georgia. They took the fortress of Gagi and raided other areas. George III responded by invading Arran in 1166, devastating the land and taking prisoners. The Shaddadids ruled Ani for about 10 years, but in 1174, George III captured their leader and took Ani again.

Queen Tamar's Reign

The unified Georgian monarchy kept its independence from the Byzantine and Seljuk empires during the 11th century. It grew strong under David IV the Builder (1089–1125). He pushed back Seljuk attacks and completed the unification of Georgia by taking back Tbilisi in 1122. Despite some family conflicts, the kingdom continued to thrive under Demetrios I (1125–1156), George III (1156–1184), and especially his daughter Tamar (1184–1213).

As the Byzantine Empire weakened and the Great Seljuk Empire broke apart, Georgia became a leading nation in the region. At its largest, it stretched from present-day Southern Russia to Northern Iran, and west into Anatolia. This period was the Georgian Golden Age, from the late 11th to the 13th centuries. It was a time of great power and development.

During the Golden Age, Georgian art, painting, and poetry flourished. This included beautiful church art and the first major works of non-religious literature. It was a time of military, political, economic, and cultural growth. It also saw a "Georgian Renaissance," where literature, philosophy, and architecture thrived.

Queen Tamar not only protected her empire from more Turkish invasions but also calmed internal problems. She even dealt with a coup led by her Russian husband. To keep peace with a neighboring empire, she sent a document in Arabic promising friendship.

In the early 1190s, the Georgian government started getting involved in the affairs of other states. They helped local princes and made Shirvan a state that paid tribute to Georgia. The Eldiguzid ruler tried to stop Georgia, but he was defeated in the Battle of Shamkor in 1195.

Freeing Armenia was very important to Georgia's foreign policy. Tamar's armies, led by two Christian Kurdish generals, took over fortresses and cities towards the Ararat Plain. They reclaimed many areas from Muslim rulers.

Süleymanshah II, the Seljuqid sultan, gathered his armies and marched against Georgia. But his camp was attacked and destroyed by David Soslan at the Battle of Basian in 1203 or 1204. The queen spoke to her troops from the church balcony before the battle. After this victory, Georgians took the town of Dvin and entered other territories.

In 1206, the Georgian army, led by David Soslan, captured Kars and other strongholds. This campaign happened because the ruler of Erzerum refused to submit to Georgia. By 1209, Georgia challenged the Ayyubid rule in the Armenian highlands. The Georgian army surrounded the city of Khlat. The Ayyubid Sultan gathered a large Muslim army to help. During the siege, a Georgian general was captured. The Sultan agreed to release him in return for a 30-year truce with Georgia.

A remarkable event during Tamar's reign was the founding of the Empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1204. This new state was created in the northeast of the weakening Byzantine Empire. Georgian armies helped Alexios I of Trebizond and his brother, who were Tamar's relatives. They were Byzantine princes who grew up in the Georgian court. Tamar wanted to create a friendly state near Georgia.

As a response to an attack on the Georgian-controlled city of Ani, where 12,000 Christians were killed in 1208, Queen Tamar invaded and conquered cities in Persia. These included Tabriz, Ardabil, Khoy, and Qazvin.

Georgia's power grew so much that in Tamar's later years, the kingdom focused on protecting Georgian monasteries in the Holy Land. Eight of these were in Jerusalem. A historian of Saladin reported that after Saladin conquered Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent envoys to ask for the return of Georgian monastery properties. Her efforts seemed to be successful.

Jacques de Vitry, a church leader in Jerusalem at that time, wrote about the Georgians:

There is also in the East another Christian people, who are very warlike and valiant in battle, being strong in body and powerful in the countless numbers of their warriors...Being entirely surrounded by infidel nations...these men are called Georgians, because they especially revere and worship St. George...Whenever they come on pilgrimage to the Lord's Sepulchre, they march into the Holy City...without paying tribute to anyone, for the Saracens dare in no wise molest them...

Nomadic Invasions and Decline

Mongol Rule

The Kingdom of Georgia faced major challenges with the arrival of nomadic invaders. The Mongol invasions in the 13th century severely weakened the kingdom.

George V the Brilliant

In 1334, Shaykh Hasan was made governor of Georgia by Abu Sai'd. The weak ruler Abu Sa'id Khan could not stop his state from declining. In 1335, after his death, the Ilkhanate (Mongol state) fell into chaos. George V took advantage of this situation. He stopped paying tribute to the Mongols and forced their army out of Georgia. He successfully brought back the country's strength and Christian culture.

During his rule, Armenian lands, including Ani, were part of the Kingdom of Georgia. In the 1330s, George protected the southwestern province of Klarjeti from advancing Ottoman tribesmen. He also helped Anna Anachoutlou become queen of the neighboring Empire of Trebizond in 1341. He also led a successful campaign against Shirvan.

George V's efforts to unite Georgia and free it from Mongol rule helped the country's economy recover. Trade and crafts grew in Georgian cities. Trade relations were restored with cities in the Middle East, the North, and even European city-states, especially in Northern Italy.

George V had friendly relations with King Philip VI of France. He wrote to the French King, saying he was ready to help free the "Holy Lands" of Syria-Palestine with 30,000 soldiers. The widespread use of the Jerusalem cross in Medieval Georgia, which inspired the modern national flag of Georgia, is thought to be from George V's reign.

The Black Death

One of the main reasons for Georgia's decline was the bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death. It first arrived in 1346. It was brought by soldiers returning from a military trip in southwestern Georgia. It is believed that the plague killed a large part, possibly half, of the Georgian population. This further weakened the kingdom and its military.

Timur's Invasions

After the terrible invasions by Timur (a powerful conqueror), the Kingdom of Georgia became very weak.

Turkmen Invasions

After Timur's death in 1405, his empire began to fall apart. The Turkomans, especially the Kara Koyunlu clan, were among the first to rebel. They took advantage of Georgia's weakness and attacked. It seems George VII of Georgia was killed in one of these attacks. Constantine I of Georgia, fearing more invasions, allied with the Shirvanshah to fight the Turkomans. However, he was defeated and captured in the Battle of Chalagan. Constantine behaved very proudly in captivity, which angered the Turkoman leader, who ordered his execution along with 300 Georgian nobles.

Alexander I of Georgia tried to strengthen his weakening kingdom. He faced constant invasions by Turkoman tribes. Alexander re-conquered Lori from the Turkomans in 1431, which was important for securing Georgia's borders. Around 1434/5, Alexander encouraged an Armenian prince to attack the Kara Koyunlu. In 1440, Alexander refused to pay tribute to Jahan Shah of the Kara Koyunlu. In March, Jahan Shah invaded Georgia with 20,000 troops, destroyed Samshvilde, and sacked the capital city Tbilisi. He killed thousands of Christians and demanded a heavy payment from Georgia before returning to Tabriz. He also led another military trip against Georgia in 1444. His forces met those of Alexander's successor, King Vakhtang IV, but the fighting was not decisive.

Because of foreign invasions and internal conflicts, the unified Kingdom of Georgia ended after 1466. It split into several smaller political units. The Kara Koyunlu Turkoman group was defeated by the Aq Qoyunlu, another Turkoman group. The Aq Qoyunlu took advantage of Georgia's division. Georgia was attacked at least twice by Uzun Hasan, the Aq Qoyunlu prince, in 1466, 1472, and possibly 1476–7. Bagrat VI of Georgia, who temporarily ruled most of Georgia, had to make peace with the invaders by giving up Tbilisi. Only after Uzun Hasan's death (1478) could the Georgians get their capital back.

In the winter of 1488, the Ak Koyunlu Turkomans attacked Georgia's capital, Tbilisi. They took the city after a long siege in February 1489. Alexander II of Imereti, another person who wanted the throne, took advantage of this invasion and seized control of Imereti. The occupation of the capital did not last long, and Constantine II of Georgia was able to push them back. However, it was still very costly for the Georgians. Ismail I, who founded the Safavid dynasty, formed an alliance with the Georgians in 1502. They decisively defeated the Aq Qoyunlu that same year, ending their state and their invasions.

Final Breakup

The unified Kingdom of Georgia finally broke apart after 1466.

Government and Society

Coins and Money

Coins from Bagrat IV (ruled 1027–1072) had both Greek and Georgian writing. By the time of Demetrius I (ruled 1125-1154), George III (ruled 1156–1184), David IV (ruled 1089–1125), and Tamar (ruled 1184–1213), coins were made with titles like "king of kings" and "queen of queens." Georgia used Arabic as a common language for trade with Islamic countries. Bilingual coins showed the good relationship between Georgia and the Caliphate.

Demetrius I only made copper coins. His coins had a mix of Georgian and Muslim styles. One side of a coin had the name of the Caliph of Baghdad. The other side had the king's initial "D" in Georgian and his title "Sword of the Messiah" in Arabic. Copper coins from George IV (ruled 1213-1223) show the year 1210. This suggests his mother gave him a lot of royal power around that time.

It's important that Georgia only minted copper coins starting with Demetrius I. This was because there was a shortage of silver in the Near East. This shortage ended in the 13th century. A lot of silver came to the Middle East after the Mongol invasion of China in 1213. When Georgia's silver supply returned, Queen Rusudan (ruled 1223–1245) was able to make silver coins in 1230.

Georgian coins showed foreign influence when the kingdom was under Mongol rule in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. They had writing in Georgian, Arabic, and Persian. During the time of Töregene Khatun (ruled 1244-1245), silver coins made in Tbilisi said "The Great Mongol Alush (Ulush) Bek." This meant "Money issued by the Great Mongol Viceroy." At the same time, David VI (ruled 1245-1259) made copper coins. His coins showed the king on a horse, and the back had writing in Persian. David VI ruled with his cousin David VII (ruled 1248–1259). Their joint silver coins were rare and likely made in Kutaisi.

Religion and Culture

Between the 11th and early 13th centuries, Georgia had a golden age of politics, economy, and culture. The Bagrationi dynasty managed to unite the western and eastern parts of the country. To do this, kings relied a lot on the Church. They gave the Church many economic benefits, tax exemptions, and large land grants. At the same time, kings like David the Builder (1089–1125) used their power to influence church matters.

For example, David called the 1103 council of Ruisi-Urbnisi. This council strongly criticized Armenian Miaphysitism. It also gave great power to his friend and advisor George of Chqondidi, second only to the Patriarch. For centuries after, the Church remained a very important institution. Its economic and political power was always at least equal to that of the main noble families.

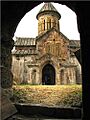

During the Middle Ages, Christianity was central to Georgian culture. Special forms of art were created for religious purposes. These included calligraphy, polyphonic church singing, and beautiful cloisonné enamel icons like the Khakhuli triptych. Georgian architecture developed a "cross-dome style" for churches. Famous examples include the Gelati Monastery and Bagrati Cathedral in Kutaisi, the Ikalto Monastery, and the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta.

Important Georgian Christian cultural figures include Euthymius of Athos (955–1028) and George of Athos (1009–1065). Philosophy also thrived from the 11th to 13th centuries, especially at the Gelati Monastery Academy. Here, Ioane Petritsi tried to combine Christian, Aristotelian, and Neoplatonic ideas.

Tamar's reign also continued the artistic growth started by earlier kings. While Georgian writings still focused on Christian values, religious themes became less dominant. Non-religious literature grew, leading to the epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin (Vepkhistq'aosani) by Rustaveli. This poem is seen as the greatest achievement of Georgian literature. It celebrates medieval ideals like chivalry, friendship, and courtly love.

Missionary Work

From the 10th century, Georgians played a big role in spreading Christianity in the Caucasus mountains. The Georgian Church succeeded where others failed in bringing Christianity to these areas. This is shown by old writings and Christian buildings with Georgian inscriptions in places like Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan. The golden age of Georgian monasteries lasted from the 9th to the 11th century. During this time, Georgian monasteries were founded outside the country, including on Mount Sinai, Mount Athos (the Iviron monastery), and in Palestine.

Legacy

Artistic Inheritance

-

Detail of the Khakhuli Triptych

-

Atskuri Triptych

-

David IV's processional cross

-

Anchi Gospel - 12th century gospel in Georgian language and Nuskhuri alphabet

See also

- List of the Kings of Georgia

- Georgian monarchs family tree

- Monarchism in Georgia

- Style of the Georgian sovereign

- List of historical states of Georgia