Tamar of Georgia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Tamar the Great |

|

|---|---|

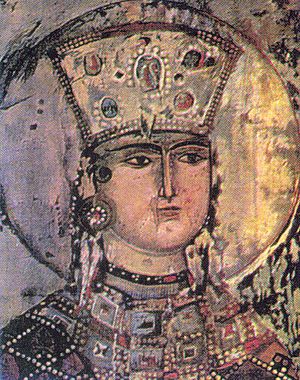

Fresco at the church of Dormition in Vardzia

|

|

| Queen of Georgia (more...) | |

| Reign | 27 March 1184 – 18 January 1213 |

| Coronation | 1178 as co-regent 1184 as queen-regnant Gelati Monastery |

| Predecessor | George III |

| Successor | George IV |

| Born | c. 1160 |

| Died | 18 January 1213 (aged 52–53) Agarani Castle |

| Spouse | Yuri Bogolyubsky (1185–1187) David Soslan (1191–1207) |

| Issue | George IV Rusudan |

| Dynasty | Bagrationi dynasty |

| Father | George III of Georgia |

| Mother | Burdukhan of Alania |

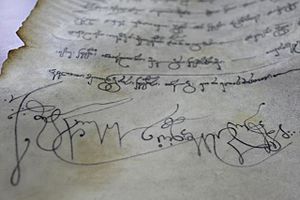

| Religion | Georgian Orthodox Church  Royal monograms |

| Khelrtva |  |

Tamar the Great (Georgian: თამარ მეფე, romanized: tamar mepe, meaning "King Tamar") was the Queen of Georgia from 1184 to 1213. She ruled during Georgia's "Golden Age," a time when the country was very strong and successful. Tamar was part of the Bagrationi dynasty, a famous royal family. She was the first woman to rule Georgia on her own, which was a big deal! People even called her mepe ("king") to show how powerful she was.

Tamar's father, George III, made her a co-ruler in 1178. This meant she shared power with him. After her father died, Tamar became the full queen. At first, some powerful nobles didn't want her to rule. But Tamar managed to deal with them. She then focused on making Georgia stronger, especially as the Seljuk Turks, who were Georgia's enemies, became weaker.

Tamar had a strong army and used it to expand Georgia's influence. Her kingdom became very powerful in the Caucasus region. This power lasted until the Mongols invaded about 20 years after Tamar's death.

Tamar was married twice. Her first marriage was to a prince named Yuri from Kievan Rus' (an old kingdom in Eastern Europe). They were married from 1185 to 1187, but Tamar divorced him and sent him away. Yuri tried to take over Georgia later, but he failed. In 1191, Tamar chose her second husband, an Alan prince named David Soslan. They had two children, George and Rusudan, who both became rulers of Georgia after her.

Tamar's time as queen was known for great political and military victories, as well as amazing cultural achievements. Because she was a successful female ruler, she became a very important and admired figure in Georgian art and history. She is still a strong symbol in Georgian popular culture today.

Contents

Early Life and Becoming Queen

Tamar was born around 1160. Her parents were George III, the King of Georgia, and Burdukhan, who was a princess from Alania. Tamar might have had a younger sister named Rusudan, but she is only mentioned once in old writings about Tamar's rule. The name Tamar comes from Hebrew and was popular with the Georgian Bagrationi royal family. This was because they believed they were related to David, a famous king from the Bible.

When Tamar was young, there was a big problem in Georgia. In 1177, some nobles rebelled against her father, King George III. They wanted to replace him with his nephew, Demna. The nobles, led by Ivane Orbeli, wanted to make the king weaker. But George III stopped the rebellion and punished the noble families involved. Ivane Orbeli was killed, and his family was forced to leave Georgia. Demna died in prison soon after.

After the rebellion, King George III made Tamar a co-ruler in 1178. He crowned her to make sure there would be no arguments about who would rule after he died. He also brought in new people from different backgrounds to work in the government, to reduce the power of the old noble families.

Early Reign and First Marriage

Tamar ruled with her father for six years. When he died in 1184, Tamar became the sole ruler. She was crowned a second time at the Gelati cathedral in western Georgia. She inherited a strong kingdom, but the powerful nobles still wanted more control. Many nobles were against Tamar becoming queen. They were reacting to her father's strict rules, and they also thought a woman would be a weak ruler.

Tamar's aunt, Rusudan, and the church leader, Catholicos-Patriarch Michael IV, were very important in helping Tamar become queen. However, Tamar had to give in to some demands from the nobles. She made Catholicos-Patriarch Michael a chancellor, which put him in charge of both church and government matters.

Tamar was also forced to remove some of her father's trusted officials. One of them was Kubasar, a general who had helped George III control the nobles. However, Tamar's first attempts to reduce the power of the nobles were not very successful. She tried to use a church meeting to remove Catholicos-Patriarch Michael, but she failed. Also, the noble council, called Darbazi, insisted on having the right to approve the queen's decisions.

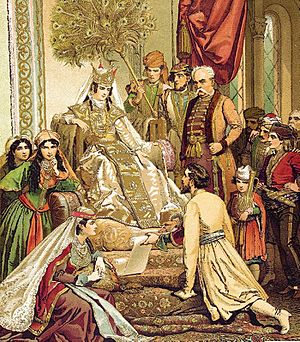

Finding a husband for Queen Tamar was very important for the country. The nobles wanted her to marry so there would be a leader for the army and an heir to the throne. Different groups of nobles tried to pick a husband who would help them gain more power. The group led by Abulasan won. Tamar's aunt Rusudan and the council of nobles approved their choice. They picked Yuri, the son of a prince who had been killed in Vladimir-Suzdal. Yuri was living as a refugee among the Kipchaks in the North Caucasus. A powerful merchant named Zankan Zorababeli was sent to bring Yuri to Tbilisi. Yuri arrived in Georgia in 1185 and married the queen.

Yuri was a brave soldier and good-looking, but he was also difficult. He soon had problems with Tamar. Their marriage issues were connected to struggles for power at the royal court. Tamar was becoming more determined to rule on her own. A major change happened when the powerful Catholicos-Patriarch Michael died. Tamar replaced him with her supporter, Anton Gnolistavisdze, as chancellor. Tamar slowly gained more power and gave important jobs to nobles who were loyal to her, especially the Mkhargrdzeli family.

Second Marriage

In 1187, Tamar convinced the noble council to let her divorce Yuri. He was sent away to Constantinople. Some Georgian nobles who wanted to limit Tamar's power helped Yuri try to take over twice, but he failed and disappeared after 1191. The queen chose her second husband herself. He was David Soslan, an Alan prince. Some historians say he was related to an earlier Georgian king, George I. David was a skilled military leader and became Tamar's main supporter. He helped her defeat the rebellious nobles who had sided with Yuri.

Tamar and David had two children. Their son, George-Lasha, was born in 1192 or 1194 and later became King George IV. Their daughter, Rusudan, was born around 1195 and became queen after her brother.

David Soslan was called a king consort, meaning he was a king because he was married to the queen. He appeared in art, on official documents, and on coins. This was important to show that the kingdom had a male leader for the army. However, David was still below Tamar in power. Tamar continued to be called mep’et’a mep’e – "king of kings." In Georgian, the word mep'e ("king") doesn't always mean a man. It can mean a "sovereign" or ruler. The word for a female queen is dedop'ali, which was used for wives or other female relatives of kings. Tamar was sometimes called dedop'ali, but the title mep'e was used to show her unique and powerful position as a female ruler.

Foreign Policy and Military Campaigns

Fighting Muslim Neighbors

Once Tamar had full control and strong support from David Soslan and loyal noble families, she continued Georgia's policy of expanding its territory. Earlier conflicts had slowed Georgia's growth, but under Tamar, especially after her first ten years of rule, Georgia became very active again.

In the early 1190s, Georgia started getting involved in the affairs of its neighbors, like the Eldiguzids and Shirvanshahs. Georgia helped local princes and made Shirvan a tributary state, meaning it had to pay tribute to Georgia. The Eldiguzid ruler, Abu Bakr, tried to stop Georgia, but David Soslan defeated him at the Battle of Shamkor in 1195. Abu Bakr lost his capital city, though he got it back a year later.

Freeing Armenia was a very important goal for Georgia. Tamar's armies, led by two Christian generals, Zakare and Ivane Mkhargrdzeli, took over many fortresses and cities in the Ararat Plain. They reclaimed these areas from Muslim rulers.

The Seljuqid sultan of Rûm, Süleymanshah II, was worried by Georgia's successes. He gathered his armies and marched against Georgia. But David Soslan attacked and destroyed his camp at the Battle of Basian in 1203 or 1204. Tamar's historian wrote about how the army gathered at the cave-town of Vardzia before going to Basian, and how the queen spoke to her troops from the church balcony. After this victory, between 1203 and 1205, Georgians captured the city of Dvin. They also entered the lands of the Ahlatshahs twice and defeated the rulers of Kars, Erzurum, and Erzincan.

In 1206, the Georgian army, led by David Soslan, captured Kars and other strongholds. This campaign started because the ruler of Erzerum refused to obey Georgia. The ruler of Kars asked the Ahlatshahs for help, but they couldn't respond. The Ahlatshahs' lands were soon taken over by the Ayyubid Sultanate in 1207. By 1209, Georgia challenged Ayyubid rule in eastern Anatolia and fought to free southern Armenia. The Georgian army surrounded Khlat. In response, the Ayyubid Sultan al-Adil I gathered a large Muslim army. During the siege, the Georgian general Ivane Mkhargrdzeli was accidentally captured by al-Awhad, an Ayyubid ruler. Using Ivane as a bargaining chip, al-Awhad agreed to release him in exchange for a 30-year peace with Georgia. This stopped the Georgian threat to the Ayyubids and left the Lake Van region to the Ayyubids.

In 1209, the Mkhargrzeli brothers attacked Ardabil. Georgian and Armenian records say this was revenge for the local Muslim ruler's attack on Ani and his killing of Christians there. In a final burst of power, the brothers led an army through Nakhchivan and Julfa to Marand, Tabriz, and Qazvin in northwest Iran. They looted many settlements along the way. Georgians reached places where no one had ever heard of them. These victories brought Georgia to its peak of power and glory. It created a large empire that stretched from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea and from the Caucasus Mountains to Lake Van.

Trebizond and the Middle East

One important event during Tamar's reign was the creation of the Empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea coast in 1204. This new state was founded by Alexios I Megas Komnenos and his brother, David. They were helped by Georgian troops. Alexios and David were relatives of Tamar and had grown up in the Georgian court after fleeing the Byzantine Empire. Tamar's historian says the reason for the Georgian expedition to Trebizond was to punish the Byzantine emperor Alexios IV Angelos. He had taken money that the Georgian queen was sending to monasteries in Antioch and Mount Athos. However, Tamar likely wanted to take advantage of the Western European Fourth Crusade against Constantinople. She wanted to create a friendly state near Georgia and support her relatives, the Komnenoi, who had lost their power.

Tamar wanted to use the weakness of the Byzantine Empire and the defeat of the Crusaders by the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. She aimed to make Georgia more important on the world stage and take on the role of protecting Christians in the Middle East, a role previously held by the Byzantine emperors. Christian Georgian missionaries were active in the North Caucasus, and Georgian monks lived in communities all over the Eastern Mediterranean. Tamar's records praise her for protecting Christianity and supporting churches and monasteries from Egypt to Bulgaria and Cyprus.

The Georgian court was especially concerned with protecting Georgian monasteries in the Holy Land. By the 12th century, eight Georgian monasteries were in Jerusalem. Saladin's biographer, Bahā' ad-Dīn ibn Šaddād, wrote that after the Ayyubids conquered Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent messengers to Saladin. She asked him to return the possessions that had been taken from the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem. We don't know Saladin's exact answer, but it seems Tamar's efforts were successful. Jacques de Vitry, a bishop who lived shortly after Tamar, wrote that Georgians were allowed to enter Jerusalem freely with their banners, unlike other Christian pilgrims. Ibn Šaddād also claimed that Tamar offered 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin to get the relics of the True Cross, which Saladin had taken after the Battle of Hattin. However, she did not succeed.

Golden Age

Feudal Monarchy

Georgia's political and cultural achievements during Tamar's time were built on a long history. Tamar's success was largely due to the changes made by her great-grandfather, David IV, and the efforts of David III and Bagrat III. These earlier kings had united the Georgian kingdoms in the early 11th century. Tamar was able to build on their successes. By the end of Tamar's reign, Georgia was at its strongest and most respected point in the Middle Ages.

Tamar's kingdom stretched from the Greater Caucasus mountains in the north to Erzurum in the south. It went from the Zygii people in the northwest to near Ganja in the southeast. It was a large empire across the Caucasus region. Northern and central Armenia were ruled by the loyal Zachariad family, Shirvan was a state that paid tribute, and Trebizond was an ally. A historian from Tamar's time praised her as the ruler of lands "from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea, from Speri to Derbend, and all the Caucasus up to Khazaria and Scythia."

The royal title became even grander. It now showed not only Tamar's rule over the traditional parts of Georgia but also her power over neighboring lands. For example, on coins and documents issued in her name, Tamar was called:

The queen never became an absolute ruler, and the noble council still had power. However, Tamar's own strong reputation and the growth of patronq'moba – a Georgian type of feudalism – kept the powerful princes from breaking up the kingdom. This was a classic period for Georgian feudalism. Trying to introduce feudal practices in new areas sometimes met with resistance. For example, there was a revolt among the mountain people of Pkhovi and Dido on Georgia's northeastern border in 1212. Ivane Mkhargrzeli put it down after three months of hard fighting.

With busy trading centers now under Georgia's control, new wealth came to the country and the royal court from industry and trade. Money taken from neighboring states and war spoils added to the royal treasury. This led to the saying that "the peasants were like nobles, the nobles like princes, and the princes like kings."

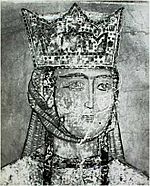

Culture

With this wealth came a burst of unique Georgian culture. It was a mix of Christian, non-religious, Byzantine, and Iranian influences. Even so, Georgians still felt connected to the Byzantine West rather than the Islamic East. The Georgian monarchy wanted to show its strong connection to Christianity and present its rule as given by God. During this time, the style of Georgian Orthodox churches was updated, and many large cathedrals with domes were built. The way royal power was shown, which came from the Byzantine Empire, was changed to highlight Tamar's special position as a woman ruling on her own. The five surviving large church paintings of the queen are based on Byzantine art. But they also show Georgian themes and Persian ideas of female beauty. Even though Georgia's culture leaned towards Byzantium, its close trade ties with the Middle East are seen on Georgian coins from that time. These coins had writing in both Georgian and Arabic. A series of coins made around 1200 in Queen Tamar's name showed a local version of the Byzantine front side and Arabic writing on the back, calling Tamar the "Champion of the Messiah."

The Georgian histories from that time praised Christian values. Religious writings continued to be popular, but non-religious literature became more important. This new literature was very original, even though it was influenced by neighboring cultures. This trend reached its peak with Shota Rustaveli's epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin (Vepkhistq'aosani). This poem celebrates the ideals of "chivalry" and is considered the greatest achievement of Georgian literature.

Death and Burial

Tamar lived longer than her husband, David Soslan. She died from a "terrible disease" near her capital city, Tbilisi. Before she died, she had already crowned her son, Lasha-Giorgi, as co-ruler. Tamar's historian says the queen suddenly became ill while talking about state matters with her ministers at Nacharmagevi castle near Gori. She was taken to Tbilisi and then to the nearby Agarani Castle, where she died. Her people mourned her deeply. Her body was moved to the cathedral of Mtskheta and later to the Gelati Monastery. Gelati was the traditional burial place for the Georgian royal family. Most historians believe Tamar died in 1213, but some signs suggest she might have died earlier, in 1207 or 1210.

Later, many legends appeared about where Tamar was buried. One story says she was buried in a secret niche at Gelati monastery to protect her grave from enemies. Another story suggests her body was reburied in a faraway place, maybe in the Holy Land. A French knight named Guillaume de Bois wrote a letter from Palestine in the early 13th century. He claimed he heard that the king of the Georgians was going to Jerusalem with a huge army and had already conquered many cities. The report said he was carrying the body of his mother, the "very powerful queen Tamar." She had not been able to visit the Holy Land during her life and had asked to be buried near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

In the 20th century, finding Tamar's grave became a topic of study and public interest. The Georgian writer Grigol Robakidze wrote in 1918: "So far, nobody knows where Tamar's grave is. She belongs to everyone and to no one: her grave is in the heart of the Georgian. And in the Georgians' perception, this is not a grave, but a beautiful vase in which an unfading flower, the great Tamar, flourishes." Most experts still believe Tamar is buried at Gelati, but archaeological studies, starting with Taqaishvili in 1920, have not found her grave there.

Legacy and Popular Culture

Medieval Times

Over many centuries, Queen Tamar has become a very important figure in Georgian history. People started calling her reign a "Golden Age" even when she was alive. Tamar became the main focus of this era. Several medieval Georgian poets, including Shota Rustaveli, said Tamar inspired their works. A legend says Rustaveli was deeply in love with the queen and spent his last days in a monastery. A dramatic scene in Rustaveli's poem, where King Rostevan crowns his daughter Tinatin, is a symbol of George III making Tamar a co-ruler. Rustaveli wrote about this: "A lion cub is just as good, be it female or male."

The queen was praised in several poems written at the time, like Chakhrukhadze's Tamariani and Ioane Shavteli's Abdul-Mesia. She was also praised in historical writings, especially in two accounts about her reign: The Life of Tamar, Queen of Queens and The Histories and Eulogies of the Sovereigns. These became the main sources for making Tamar a saintly figure in Georgian literature. The writers praised her as a "protector of the widowed" and "the thrice blessed." They especially highlighted Tamar's good qualities as a woman: her beauty, humility, kindness, loyalty, and purity. Although Tamar was made a saint by the Georgian church much later, she was called a saint even during her lifetime in a Greek-Georgian note found in the Vani Gospels manuscript.

People admired Tamar even more because of what happened after she died. Within 20 years of her death, invasions by the Khwarezmians and Mongols suddenly ended Georgia's power. Later periods of national revival were too short to equal the achievements of Tamar's reign. All of these things helped create a strong admiration for Tamar. This made it hard to tell the difference between the perfect queen people imagined and the real person.

In popular memory, Tamar's image has become legendary and romantic. Many folk songs, poems, and stories show her as an ideal ruler and a holy woman. Sometimes, she was even given qualities of pagan gods and Christian saints. For example, in an old Ossetian legend, Queen Tamar's son is born from a sunbeam shining through a window. Another myth, from the Georgian mountains, connects Tamar with Pirimze, a pagan weather god who controls winter. Similarly, in the highland area of Pshavi, Tamar's image blended with a pagan goddess of healing and female fertility.

While Tamar sometimes went with her army and helped plan battles, she never fought directly. However, the memory of the military victories during her reign contributed to Tamar's other popular image: that of a perfect warrior-queen. This also appeared in The Tale of Queen Dinara, a popular 16th-century Russian story about a fictional Georgian queen fighting against the Persians. The Tsar of All the Russias Ivan the Terrible encouraged his army before the capture of Kazan by talking about Tamar's battles. He described her as "the most wise Queen of Iberia, with the intelligence and courage of a man."

Modern Times

Much of how people see Queen Tamar today was shaped by 19th-century Romanticism and the growing feeling of nationalism among Georgian thinkers. In Russian and Western writings of the 19th century, Queen Tamar's image reflected European ideas about the Orient (which included Georgia) and the role of women there. The Tyrolean writer Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer called Tamar a "Caucasian Semiramis" (a legendary Assyrian queen). The Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, fascinated by the "exotic" Caucasus, wrote the romantic poem Tamara (Russian: Тамара; 1841). In it, he used an old Georgian legend about a siren-like mountain princess, giving her the name of Queen Tamar. Knut Hamsun's 1903 play Queen Tamara was not as successful. Critics saw it as "a modern woman dressed in a medieval costume" and thought it was "a comment on the new woman of the 1890s." The Russian conductor Mily Balakirev composed a symphonic poem called "Tamara."

In Georgian literature, Tamar was also romanticized, but in a different way than in Russian and Western European views. Georgian romantic writers followed a medieval tradition. They showed Tamar as a gentle, saintly woman who ruled a country that was always at war. This feeling was also inspired by the discovery of a 13th-century wall painting of Tamar in the ruined Betania Monastery. Prince Grigory Gagarin found and restored it in the 1840s. This painting was copied many times and spread throughout Georgia. It inspired the poet Grigol Orbeliani to write a romantic poem about it. Also, Georgian writers, reacting to Russian rule in Georgia and the loss of national institutions, compared Tamar's era to their own time. They sadly wrote about the glorious past that was now gone. Because of this, Tamar became a symbol of Georgia's golden age, and this idea continues to this day.

Tamar's marriage to the Rus' prince Yuri has been the subject of two famous stories in modern Georgia. Shalva Dadiani's play, originally called The Unfortunate Russian (უბედური რუსი; 1916–1926), was criticized by Soviet critics. They said it twisted the "centuries-long friendship of the Russian and Georgian peoples." Under pressure from the Communist Party, Dadiani had to change both the title and the story to fit the official Soviet ideas. In 2002, a funny short story called The First Russian (პირველი რუსი) by young Georgian writer Lasha Bughadze caused a lot of anger. It focused on a difficult wedding night for Tamar and Yuri. This led to a nationwide debate, with heated discussions in the media, the Parliament of Georgia, and the Georgian Orthodox Church.

She is a character you can play as the leader of Georgia in the video game Civilization VI.

Veneration

Tamar has been canonized (declared a saint) by the Georgian Orthodox Church as the Holy Righteous Queen Tamar (წმიდა კეთილმსახური მეფე თამარი, ts'mida k'etilmsakhuri mepe tamari; also known as "Right-believing Tamara"). Her feast day is celebrated on May 1 (according to the Julian Calendar, which is May 14 on the Gregorian Calendar) and on the Sunday of the Holy Myrrh-Bearing Women. The Antiochian Orthodox Church celebrates the feast of St. Tamara on April 22.

Genealogy

The chart below shows the family tree of Tamar and her family, from her grandfather to her grandchildren.

| Genealogy of Tamar and her family | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Tamara de Georgia para niños

In Spanish: Tamara de Georgia para niños

- Order of Queen Tamara (disambiguation)

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |