Orientalism facts for kids

Orientalism is a term used in art, literature, and cultural studies. It describes how writers, designers, and artists from the Western world have shown or copied parts of the Eastern world (also called the "Orient"). For example, many 19th-century paintings of the Middle East were a type of Orientalist art. Western books were also very interested in Eastern themes.

Since Edward Said wrote his book Orientalism in 1978, many experts use the term differently. They use it to mean a Western attitude that often looks down on societies in the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa. Said explained that the West often sees these societies as unchanging and not developed. This way of thinking creates a picture of Eastern culture that can be studied and copied to support Western power. Said believed this also made Western society seem developed, smart, flexible, and better. This allowed the Western imagination to see Eastern cultures as both exciting and a threat.

Contents

What Does Orientalism Mean?

Where Did the Word Come From?

The word "Orientalism" comes from "Orient." This word refers to the East, in contrast to the "Occident," which means the West. The word "Orient" came into English from French. Its original Latin meaning was "the eastern part of the world" or "where the sun rises."

Over time, the meaning of "Orient" changed. In the 1300s, Geoffrey Chaucer used it to mean countries east of the Mediterranean Sea and Southern Europe. Later, in 1952, Aneurin Bevan used it to include East Asia. Edward Said said that Orientalism helps the West control other parts of the world. This control happens politically, economically, culturally, and socially, not just in the past but also today.

Orientalism in Art

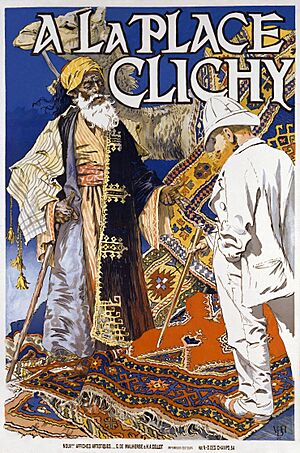

In art history, "Orientalism" describes paintings by mostly 19th-century Western artists. These artists focused on Eastern subjects after traveling in Western Asia. Back then, artists and scholars who studied the East were called Orientalists. In France, the art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary made the term "Orientalist" sound negative.

Despite this, the French Society of Orientalist Painters was started in 1893. Jean-Léon Gérôme was its honorary president. In Britain, "Orientalist" simply meant "an artist." This society helped artists see themselves as part of a special art movement. Orientalist painting is often seen as a part of 19th-century academic art.

There were different styles of Orientalist art. Some artists, like Gustav Bauernfeint, were realists. They carefully painted what they saw. Others imagined Eastern scenes without ever leaving their studios. French painters like Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) are famous leaders of this movement.

Oriental Studies

In the 18th and 19th centuries, an "Orientalist" was a scholar who studied the languages and literature of the Eastern world. Many of these scholars worked for the East India Company. They believed that Arab culture, Indian culture, and Islamic cultures were as important as European cultures.

One such scholar was William Jones. His studies of Indo-European languages helped create modern philology, the study of language in historical and cultural context. The Company rule in India at first supported Orientalism to build good relationships with Indians. But by the 1820s, people like Thomas Babington Macaulay and John Stuart Mill pushed for Western-style education instead.

Also, the study of Hebrew and Jewish studies became popular in Britain and Germany. The academic field of Oriental studies, which included cultures of the Near East and Far East, later became Asian studies and Middle Eastern studies.

Edward Said's View

In his 1978 book Orientalism, cultural critic Edward Said gave the term a new meaning. He used it to describe a long-standing Western tradition of biased interpretations of the Eastern world. He argued that this tradition was shaped by European imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Said's book explains how Western ideas about the East were used to support power. He criticized scholars who continued to interpret Arabo-Islamic cultures from an outsider's view. Said said that the idea of "representation" is like a play. The East is a stage where the whole East is put on display. He believed that what these scholars studied was not the East itself, but the East made understandable and less scary to Western readers.

Said's book became very important in post-colonial cultural studies. His work mainly looked at Orientalism in European literature, especially French. It did not focus on visual art or Orientalist painting. However, art historian Linda Nochlin later applied Said's ideas to art. Some scholars now see Orientalist paintings as showing a myth or fantasy, not always reality.

There is also criticism of Orientalism within the Islamic world. In 2002, it was thought that about 200 books and 2,000 articles discussing Orientalism had been written by scholars in Saudi Arabia alone.

Eastern Styles in European Buildings and Design

The Moresque style of Renaissance decoration is a European version of the Islamic arabesque. It started in the late 1400s and was used in things like bookbinding for a long time. Early examples of Indian-inspired architecture are called Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture. One of the first is the Guildhall, London (1788–1789). This style became more popular in the West after books with pictures of India were published around 1795. Examples of "Hindoo" architecture include Sezincote House (c. 1805) in England and the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

Turquerie was a style that started in the late 1400s and lasted until at least the 1700s. It included using "Turkish" styles in art and adopting Turkish clothing. It also showed interest in art about the Ottoman Empire. Venice, which traded a lot with the Ottomans, was an early center for this style. France became more important in the 1700s.

Chinoiserie is a general term for the fashion of using Chinese themes in Western European decoration. It started in the late 1600s and was very popular around 1740–1770. From the Renaissance to the 1700s, Western designers tried to copy the detailed Chinese ceramics. Early signs of Chinoiserie appeared in the 1600s in countries with active East India companies. For example, Dutch pottery from Delft copied Chinese Ming-era blue and white porcelain. Early porcelain made in Germany also copied Chinese shapes for dishes and vases.

"Chinese taste" pleasure pavilions appeared in German palaces. Thomas Chippendale's mahogany tea tables and cabinets were decorated with Chinese-style patterns. Small pagodas appeared on fireplaces and full-sized ones in gardens. Kew Gardens has a large Great Pagoda designed by William Chambers. The Wilhelma (1846) in Stuttgart is an example of Moorish Revival architecture. Leighton House has a normal outside but fancy Arab-style rooms inside. It includes real Islamic tiles and Victorian Orientalizing art.

After 1860, Japonism became a big influence in Western art. This was sparked by the import of ukiyo-e Japanese prints. Many French artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were influenced by Japanese style. American artist Mary Cassatt used Japanese print elements in her work. James Abbott McNeill Whistler's The Peacock Room shows how he used Japanese traditions. California architects Greene and Greene were inspired by Japanese elements in their designs.

Egyptian Revival architecture was popular in the early and mid-1800s. It continued as a smaller style into the early 1900s. Moorish Revival architecture began in the early 1800s in Germany and was popular for synagogues. Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture appeared in the late 1800s in the British Raj (British India).

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie - Chinese House, Sanssouci Park, Potsdam, Germany, by Johann Gottfried Büring, 1755–1764

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie: Chinese Pavilion, Ekerö Municipality, Sweden, by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, 1763–1769

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie: Pagod, based on Asian figures of Budai by Johann Joachim Kändler, c. 1765, hard paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

-

Islamic inspiration: Turkish Tent, Hagaparken, Stockholm, Sweden, by Louis Jean Desprez, 1787

-

Islamic inspiration: Royal Pavilion, Brighton, UK, by John Nash, 1787–1823

-

Chinese inspiration/Chinoiserie: Chinese Tower in the Englischer Garten, Munich, Germany, by Johann Baptist Lechner, 1789–1790, reconstructed in 1952

-

Islamic inspiration: Vase Espoir, by Émile Gallé, 1889, acid-etched glass, with enamelled and gilt decoration, Musée de l'École de Nancy, Nancy, France

-

Islamic inspiration: Turkish Pavilion at the 1900 Paris Exposition, Paris, by Émile Dubuisson, c.1900

-

Japanese inspiration: Mascaron of the Praha hlavní nádraží, Prague, the Czech Republic, designed by Josef Fanta, 1901–1909

-

Thai inspiration - Monumental corbels of a Société financière française et coloniale headquarter (Rue des Mathurins no. 53), Paris, unknown architect, c.1910

-

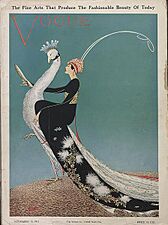

Japanese inspiration/Japonisme: Cover of Vogue, November 15, 1911, by George Wolfe Plank, chromolithograph, multiple locations

-

Mix of Egyptian Revival and Art Deco: Le Louxor Cinema, Paris, by Henri Zipcy, 1919-1921

Orientalist Art and Its History

Orientalist ideas in Western art have a long history. You can find Eastern scenes in medieval and Renaissance art. Islamic art itself has greatly influenced Western art. Eastern subjects became even more common in the 1800s, as Western countries took control of lands in Africa and Asia.

Before the 19th Century

Art from the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque periods often showed Islamic "Moors" and "Turks." These terms were used for Muslim groups in southern Europe, North Africa, and West Asia. In early Dutch paintings of Bible scenes, secondary figures like Romans wore exotic clothes that looked a bit like those from the Near East. The Three Magi in Nativity scenes were often shown this way.

Renaissance Venice was very interested in showing the Ottoman Empire in paintings and prints. Gentile Bellini, who visited Constantinople and painted the Sultan, and Vittore Carpaccio were important artists. Their pictures were more accurate, often showing men dressed in white. The use of Oriental carpets in Renaissance painting sometimes came from this interest.

Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702–1789) visited Istanbul and painted many Turkish home scenes. He even kept wearing Turkish clothes when he returned to Europe. The Scottish artist Gavin Hamilton used Middle Eastern settings in his historical paintings. This allowed Europeans in the paintings to wear local costumes, which was seen as more heroic than modern dress. Many travelers had their portraits painted in exotic Eastern clothes when they returned home. This included Lord Byron and even people who had never left Europe, like Madame de Pompadour.

French Orientalism in Art

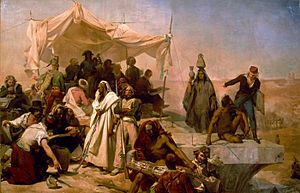

French Orientalist painting changed a lot after Napoleon's invasion of Egypt and Syria (1798–1801). This war, though not successful, made the public very interested in Egyptology. Napoleon's court painters, like Antoine-Jean Gros, recorded these events. His famous paintings, Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) and Battle of Abukir (1806), show the Emperor with many Egyptian figures.

Eugène Delacroix's first big success, The Massacre at Chios (1824), was painted before he visited Greece or the East. It showed a recent event in distant lands that had upset the public. Greece was fighting for independence from the Ottomans and was seen as exotic. Delacroix later visited Algeria (which France had recently conquered) and Morocco in 1832. He was very impressed by what he saw. He compared the North African way of life to that of the Ancient Romans. He continued to paint scenes from his trip after returning to France. Like many Orientalist painters, he found it hard to sketch women. So, many of his scenes showed Jews or warriors on horses. However, he was able to enter a women's area (harem) to sketch what became Women of Algiers. Few later harem scenes had this claim to being real.

In many of these artworks, artists showed the East as exotic and colorful, sometimes using stereotypes. These works often focused on Arab, Jewish, and other Semitic cultures. This was because artists visited these areas as France became more involved in North Africa. French artists like Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres painted many works showing Islamic culture. They emphasized both relaxation and visual beauty.

British Orientalism in Art

Britain was also very interested in the Ottoman Empire, but their involvement was often quieter. British Orientalist painting in the 1800s was more influenced by religion than by military conquest. The famous British genre painter, Sir David Wilkie, traveled to Istanbul and Jerusalem in 1840. He died on the way back. Wilkie, though not known as a religious painter, made the trip to improve religious painting. He wanted to find more real settings for Bible stories.

Other artists, like the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt and David Roberts, had similar reasons. This led to a focus on realism in British Orientalist art. The French artist James Tissot also used modern Middle Eastern landscapes for Bible subjects.

William Holman Hunt created several major paintings of Bible stories based on his Middle Eastern travels. He used variations of Arab costumes and furnishings to avoid specific Islamic styles. He also painted landscapes and everyday scenes. His Bible subjects included The Scapegoat (1856) and The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860). His painting A Street Scene in Cairo; The Lantern-Maker's Courtship (1854–61) shows a young man feeling his fiancée's face through her veil.

When Gérôme showed For Sale; Slaves at Cairo in London in 1871, many people found it offensive. This was partly because Britain had helped stop the slave trade in Egypt.

John Frederick Lewis, who lived in a traditional mansion in Cairo for several years, painted very detailed works. He showed both realistic everyday scenes of Middle Eastern life and more ideal scenes in wealthy Egyptian homes. His careful way of showing Islamic architecture, furniture, and costumes set new standards for realism. This influenced other artists, including Gérôme.

Other artists focused on landscape painting, often of desert scenes. These included Richard Dadd and Edward Lear. David Roberts (1796–1864) made architectural and landscape views, many of ancient sites. He published very popular books of lithographs from his works.

Russian Orientalism in Art and Music

Russian Orientalist art mostly focused on the areas of Central Asia that Russia was conquering. It also showed historical paintings of the Mongols, who had ruled Russia for a long time. These paintings rarely showed Mongols in a good way. The explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky helped make an exotic view of "the Orient" popular and supported Russia's expansion.

"The Five" were important 19th-century Russian composers. They worked together to create a unique national style of classical music. A key part of their style was using Orientalism. Many famous "Russian" works were composed in an Orientalist style. Examples include Balakirev's Islamey, Borodin's Prince Igor, and Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade.

In music, Orientalism can be found in different periods. For example, the alla Turca style was used by composers like Mozart and Beethoven. Music expert Richard Taruskin said that 19th-century Russian music used the East as a symbol. It was an imaginary place or a historical story. It was seen as the "other" against which Russians defined themselves.

Taruskin described Orientalism in Romantic Russian music as having melodies with many small decorations. It also had changing accompanying lines and a steady bass sound. These musical features created a feeling of: "not just the East, but the seductive East that makes one weak, enslaves, makes one passive." Orientalism is also found in music that creates an exotic feeling. This includes the influence of Javanese gamelan music in Claude Debussy's piano music. It also includes the sitar being used in songs by the Beatles.

In the United Kingdom, Gustav Holst composed Beni Mora. This piece created a slow, rich Arabian atmosphere. Orientalism also appeared in a more playful way in exotica music in the late 1950s. An example is Les Baxter's "City of Veils."

Orientalism in Pop Culture

Authors and composers are not usually called "Orientalist" in the same way artists are. But many famous figures, from Mozart to Flaubert, have created important works with Eastern subjects. Lord Byron wrote four long "Turkish tales" in poetry. He was one of the most important writers to make exotic, fantasy Eastern settings a major theme in Romanticism literature. Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida (1871) is set in Egypt. It shows a militaristic Egypt controlling Ethiopia.

In Literature

The Romantic movement in literature lasted from about 1785 to 1830. During this time, Eastern culture and objects greatly influenced Europe. Extensive travel by artists and wealthy Europeans brought back travel stories and exciting tales. This created a huge interest in all things "foreign." Romantic Orientalism used African and Asian locations, famous colonial and "native" people, folklore, and philosophies. This created a literary world of colonial exploration from a clear European viewpoint. Today, people often see this literature as a way to justify European colonial efforts and expansion.

In his novel Salammbô, Gustave Flaubert used ancient Carthage in North Africa as a contrast to ancient Rome. He showed its culture as morally corrupt. This novel greatly influenced how ancient Semitic cultures were shown later.

In Film

Edward Said argued that Orientalism continues today, especially in American movies. Many blockbuster films, like the Indiana Jones series, The Mummy films, and Disney's Aladdin series, show imagined Eastern places. These films usually show the heroes as Westerners, while the villains often come from the East. This way of showing the East continues in movies, even if it's not always true to reality.

For example, in The Tea House of the August Moon (1956), the film shows the people of Okinawa as "merry but backward." This ignored real protests by Okinawans about the American military taking their land.

In Dance

During the Romantic period of the 1800s, ballet became very interested in exotic themes. By the late 1800s, ballets were trying to capture the mysterious essence of the East. These ballets were often based on assumptions about people rather than facts. Orientalism is clear in many ballets.

The East inspired several major ballets that are still performed today. Le Corsaire first showed in 1856. Its story, based on Lord Byron's poem, takes place in Turkey. It focuses on a love story between a pirate and a beautiful slave girl. Scenes include a market where women are sold as slaves and the Pasha's Palace with his wives. In 1877, Marius Petipa choreographed La Bayadère, a love story about an Indian temple dancer and a warrior. This ballet used Indian-inspired costumes and hand gestures. It also included a 'Hindu Dance' based on the Indian dance form Kathak. Another ballet, Sheherazade, choreographed by Michel Fokine in 1910, is about a shah's wife and her forbidden relationship.

Other lesser-known ballets also show Orientalism. For example, in Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter (1862), an Englishman dreams he is an Egyptian boy who wins the love of the Pharaoh's daughter. Her costume had 'Egyptian' decorations on a tutu.

Ruth St Denis, a pioneer of modern dance in America, also explored Orientalism. Her dances were not always authentic. She got ideas from photographs, books, and museums. But the exotic feel of her dances appealed to American society women. She included Radha and The Cobras in her 'Indian' program in 1906. She also created her first 'Egyptian' work, Egypta, in 1909.

While Orientalism in dance was most popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, it is still present today. Major ballet companies still perform Le Corsaire, La Bayadere, and Sheherazade. Also, newer versions of ballets like The Nutcracker still use stereotypical 'Oriental' movements.

Eastern and Western Views

The idea of Orientalism has been used by scholars in East-Central and Eastern Europe. They use it to study how Western cultures viewed East-Central and Eastern European societies in the 1800s and during Soviet rule.

The term "re-orientalism" describes how Eastern self-representation is based on Western ideas. It challenges the old ideas of Orientalism. But it also creates new ideas to explain Eastern identities. This both breaks down and strengthens Orientalism.

Occidentalism

The term occidentalism often refers to negative views of the Western world found in Eastern societies. This comes from a sense of nationalism that grew in response to colonialism. Edward Said has been accused of "Occidentalizing" the West in his criticism of Orientalism. This means he supposedly described the West falsely, just as he said Western scholars falsely described the East. According to this view, Said made the West seem too simple and all the same. Today, the West includes not only Europe but also the United States and Canada.

In the 1700s, Qing emperors in China were fascinated by Occidenterie. These were objects inspired by Western art and architecture. This was similar to Europe's chinoiserie, which copied Chinese art. Even though it was mostly linked to the emperor's court, many Chinese people had access to Occidenterie objects because they were made in China.

Othering Cultures

The action of othering happens when groups are labeled as different. This is because of characteristics that set them apart from what is seen as normal. Edward Said argued that Western powers and influential people, like social scientists and artists, "othered" "the Orient." Ideas often start in language and then spread through society, affecting culture, economy, and politics. Much of Said's criticism of Western Orientalism is based on these trends. These ideas are also present in Asian works by Indian, Chinese, and Japanese writers and artists, in their views of Western culture. A key development is how Orientalism has appeared in non-Western movies, like Hindi-language cinema.

Said's book Orientalism has been important for understanding how "representing" others can be a way of gaining power over them. However, some recent studies suggest that Orientalism has sometimes been too simply used to mean that "othering" only involves negative qualities.

For example, the relationship between Greece and Germany during the sovereign debt crisis showed complex "othering." It included fascination mixed with looking down on others, dislike, admiration, and hopes for escaping a difficult European lifestyle. Similarly, tourism and relationships between cities and rural areas can show Orientalist dynamics. These dynamics can involve mixed feelings from those watching, and also the involvement of those being represented in either repeating or challenging stereotypes.

See also

In Spanish: Orientalismo para niños

In Spanish: Orientalismo para niños

- Allosemitism

- Arabist

- Black orientalism

- Borealism

- Chinoiserie

- Cultural appropriation

- Dahesh Museum

- Ethnocentrism

- Exoticism

- Hebraist

- Hellenocentrism

- Indomania

- Japonisme

- La belle juive

- List of artistic works with Orientalist influences

- List of Orientalist artists

- Negrophilia

- Neo-orientalism

- Noble savage

- Objectification

- Othering

- Outsider art

- Pizza effect

- Primitivism

- Romantic racism

- Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam

- Stereotypes

- Stereotypes of Arabs and Muslims in the United States

- Stereotypes of Jews

- Stereotypes of South Asians

- Turquerie

- Westsplaining

- World music

- Xenocentrism

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |